A Beginner’s Guide to Graphs — From Google Maps to Chessboards

Most of us use Google Maps without thinking twice. You open the app, check which route has the least traffic, and hit start. Then somewhere along the way – maybe you miss a turn (I do that often) – and Maps calmly recalculates your route, showing you...

Most of us use Google Maps without thinking twice. You open the app, check which route has the least traffic, and hit start. Then somewhere along the way – maybe you miss a turn (I do that often) – and Maps calmly recalculates your route, showing you a new path that still gets you to your destination.

Behind that seamless rerouting is a graph – not a chart, but a structure of nodes (places) and edges (roads) that allows Google Maps to calculate the shortest, fastest, or least congested path from point A to point B.

Once you start noticing them, you’ll realize graphs are everywhere. If you’ve ever used:

Google Maps to get from one city to another,

LinkedIn to see how you’re connected to someone,

or Git to visualize branches and merges…

…you’ve interacted with a graph.

Graphs are everywhere, in how we plan routes, recommend friends, manage project dependencies, and even predict the possible moves of a knight on a chessboard. But to use them well, we first need to understand how they’re structured and why they’re so useful.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What a graph is and how it’s used in real-world systems

The different types of graphs and how they’re represented in code

How to traverse graphs using search algorithms

And finally, how a knight’s movement in chess can be modeled using graphs, and solved using traversal techniques

Let’s start by breaking down what graphs are made of and why they show up in so many things you already use.

Table of Contents

Prerequisites

This article is beginner-friendly, and no prior knowledge of graphs is required. To follow along with the code examples, it helps to have:

Some familiarity with data structures like stacks and queues.

I use Python for the code snippets, but if you’ve worked with another language, you should be able to follow along easily.

What is a Graph?

At its core, a graph is a collection of nodes (also called vertices) and edges – connections that link those nodes together.

If it sounds simple, that’s because it is. The power of graphs isn’t in their complexity, it’s in their flexibility. You can use them to represent almost anything: people, cities, web pages, tasks, game moves, and the relationships between them.

Let’s break it down:

Nodes (Vertices)

Each node is a point in the graph. It might represent:

A location (like a city on a map)

A person (in a social network)

A page (for example, on the web)

A square (like one on a chessboard)

Edges

An edge is a connection between two nodes. It could represent:

A road between two cities

A friendship between two users

A hyperlink between two web pages

A legal knight move between two squares

Edges can have direction (one-way or two-way), weight (like distance or cost), or be simple and unweighted.

Graph Visualizer

Here’s a simple graph:

In this image:

The circles represent nodes (also called vertices)

The lines connecting them are edges, which show that two nodes are related or connected in some way

Each node is connected to one or more other nodes, forming a network of relationships.

Types of Graphs

Now that we’ve seen what a graph looks like, let’s talk about the different ways graphs can behave.

Graphs can vary in direction, weight, and structure. Understanding these types helps us choose the right graph model for the problem we’re trying to solve.

Directed Graphs

In a directed graph (also known as a digraph), connections between nodes move in a specific direction. Think of it like a one-way street – if you can drive from Point A to Point B, that doesn't necessarily mean you can drive back the same way.

A good example of this is X (Twitter). If you follow someone on X, it doesn’t automatically mean they follow you back. Your “follow” is a one-way connection, a directed edge from you to them.

This kind of graph is especially useful in situations where relationships are not mutual. On the internet, links between web pages behave the same way. Page A might link to Page B, but Page B might not link back. Similarly, in workflow systems or task pipelines, each step flows into the next in a specific order, and you generally don’t loop back – Step 1 leads to Step 2, and so on.

Undirected Graphs

An undirected graph represents relationships that go both ways. If there’s a connection between node A and node B, you can travel in either direction.

A common example is a friendship on Facebook. If you’re friends with someone, the connection is mutual by default. It wouldn’t make sense to be “half-friends”.

Undirected graphs are useful when the relationship itself is mutual and symmetrical, like shared devices on a network or road systems where travel is allowed both ways.

The key difference here is that edges are just lines, not arrows – they don’t imply flow or hierarchy, just connection.

Weighted Graphs

A weighted graph is one where each connection (edge) carries extra information, usually a number representing distance, cost, time, or importance.

Consider how you use Google Maps to get from one location to another. The app doesn’t just look for any route, it looks for the one that takes the least time, travels the shortest distance, or uses the least fuel. All of those are weights.

In a graph like this, two cities might be connected, but one road might take 5 minutes while another takes 20, so the edge between those cities isn’t just a line – it’s a line with a value.

This structure lets us make smarter decisions. We can ask questions like:

What’s the cheapest way to reach a destination?

Which route avoids the most traffic?

What’s the fastest route from node A to node Z?

If undirected and directed graphs describe who is connected to whom, weighted graphs help us understand how strong, far, or costly those connections are.

Unweighted Graphs

In an unweighted graph, all edges are treated equally. A connection either exists, or it doesn’t – there’s no extra value or cost attached.

Think of a group of friends where you only care about whether two people know each other. You’re not trying to measure how close they are or how often they talk, you just want to map the presence or absence of a relationship.

Unweighted graphs are useful for modeling systems where the existence of a connection is more important than any nuance of how strong it is. These are great for representing basic relationships, board game states, or decision trees where each path is considered equally likely or valuable.

In short, unweighted graphs are all about the “yes/no,” not the “how much.”

Cyclic Graphs

A cyclic graph is one where it’s possible to loop back to where you started. You can travel through a series of connections and eventually end up at the same node.

If you’ve ever looked at a city map or used a public transit system with circular routes, you’ve seen a cycle in action. You might start at a station, ride the train through several stops, and eventually return to where you began, without ever retracing your exact steps.

Cyclic graphs are especially useful in simulations, games, or real-world systems where loops are part of the design, like control circuits or repeated workflows. They’re a natural fit for any scenario where repetition or return paths matter.

But they can also introduce complexity, especially in algorithms that aren’t meant to handle cycles. Recognizing whether your graph has cycles is often an important first step in choosing the right traversal method.

Acyclic Graphs

An acyclic graph is the opposite of a cyclic one – there are no loops. Once you start moving through the graph, you can’t return to a node you’ve already visited by following the direction of the edges. They can either be directed or undirected graphs.

Think of task management systems where some tasks depend on others. You can't complete Task C until you’ve finished Task B, and you can't start B until A is done. There’s a natural order, and no looping back.

Acyclic graphs are common in:

Scheduling systems

Organizational charts

Tutorial progression systems (like one chapter unlocking the next)

Directed Acyclic Graphs

A Directed Acyclic Graph or DAG is a type of acyclic graph where every edge has a direction, and you can’t form any cycles. It’s like a roadmap where all roads point forward and never loop.

This structure is incredibly common in computing, especially when you need to track progress, dependencies, or history.

In Git, for example, every commit points to one or more parent commits, forming a directed graph of changes. But since commits can’t “revisit” an earlier state, the structure remains acyclic.

In package managers, a library might depend on others, but you can't have a loop. Say library A depends on B, which depends on C, which depends on A again – that would break everything. A DAG ensures that dependencies move forward, not in circles.

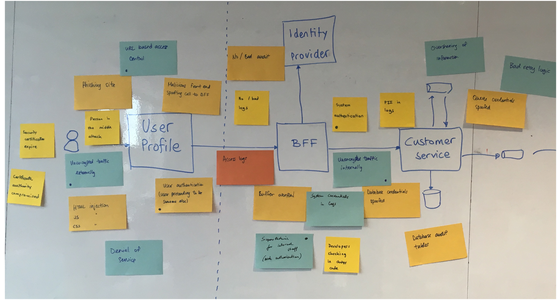

How Graphs Are Represented

So far, we’ve explored graphs as concepts and visuals with various types and behaviors. But when it’s time to work with graphs in code, we need a way to represent those connections in a structured format.

There are two common ways to represent a graph:

Adjacency List

Adjacency Matrix

Each has its strengths, and which one you use depends on the type of graph and what operations you need to perform.

Adjacency List

An adjacency list stores a graph as a collection of nodes, where each node maps to a list of its neighbors (nodes it’s connected to). An adjacency list is one of the most intuitive ways to represent a graph. But how you write this list depends on the type of graph you’re working with.

For an undirected graph, the connection goes both ways, so each edge is written twice – once for each node.

For a directed graph, each connection only flows one way, so you only write it once, in the direction it points.

Benefits:

Memory-efficient for sparse graphs (that is, not all nodes are connected)

Easy to add or remove nodes and edges

Fast to get a node’s neighbors – just read its list

Downsides:

Slower edge lookup: To check if two nodes are connected, you have to scan a list

Can be inefficient for dense graphs where most nodes connect to many others

Sorting neighbors or accessing them by index is less convenient

Adjacency Matrix

An adjacency matrix uses a 2D array (or grid) to represent connections between nodes. Each row and column corresponds to a node, and the cell at the intersection tells you whether there’s a connection.

A value of

1means there is an edge between the two nodes.A value of

0means an edge doesn’t exist between two nodes.

For an undirected graph, an edge between i and j means the connection works both ways. So if (i, j) is 1, (j, i) is also 1. This makes the matrix symmetric, that is, (i, j) == (j, i).

For a directed graph, an edge from node i to node j is at position (i, j). But this doesn’t imply that there's an edge from j to i. So in general, (i, j) ≠ (j, i).

Benefits:

Instant edge lookup between any two nodes in

O(1)time.Simple to implement and often used in low-node-count, dense graphs.

Downsides:

High space complexity – even if the graph has few edges, the matrix still takes up

O(V²)space.Inefficient for sparse graphs, where many cells are unused.

Finding neighbors requires scanning an entire row, which takes

O(V)time.

Graph Traversal

Once you’ve built a graph using adjacency lists or matrices, the next question is: how do you explore it?

Graph traversal is the process of visiting each node (and its neighbors) in a graph in a specific order. It’s a foundational technique in computer science, used in everything from web crawling to friend suggestions on social media.

Traversal is used when:

You want to search for a specific value or node.

You want to visit all nodes, for example, to analyze connectivity.

You want to solve puzzles, like mazes or routing problems.

There are two primary ways to traverse a graph: Depth-First Search (DFS) and Breadth-First Search (BFS). Let’s traverse through this graph using both methods:

Breadth-First Search (BFS)

BFS starts from a node and explores all of its immediate neighbors before moving on to the neighbors of those neighbors.

It’s commonly used in:

Finding the shortest path (in unweighted graphs)

Level-order traversal

Network broadcast simulations

from collections import deque

def bfs(graph, start):

visited = set()

queue = deque([start])

while queue:

node = queue.popleft()

# node has not been visited

if node not in visited:

print(node) # Visit the node

visited.add(node)

for neighbor in graph[node]: # Look at each neighbor of the current node

if neighbor not in visited:

queue.append(neighbor)

# Undirected graph

graph = {

'A': ['B', 'C'],

'B': ['A', 'D'],

'C': ['A', 'D'],

'D': ['B', 'E'],

'E': ['D']

}

bfs(graph, 'A')

Here’s the output of the code above:

A

B

C

D

E

What This Code Does:

Step 1: Choose a Starting Point

Pick the node where you want to begin the traversal. Add it to a queue.

Step 2: Visit the Node at the Front of the Queue

Take the first node from the queue (this is your current node) and mark it as visited. Do something with it, like printing its value.

Step 3: Add Its Neighbors to the Queue

Look at all the nodes directly connected to the current node (its neighbors). For each neighbor, if it hasn't been visited yet, add it to the end of the queue.

Step 4: Repeat Until the Queue Is Empty

Go back to Step 2. Keep visiting the node at the front of the queue and enqueue its unvisited neighbors until no more nodes are left in the queue.

Depth-First Search (DFS)

DFS dives deep into one path of the graph before backtracking and exploring other branches.

It’s useful for:

Cycle detection

Topological sorting

Solving puzzles like mazes (where the shortest path doesn’t matter)

def dfs(graph, start):

visited = set()

stack = [start]

while stack:

node = stack.pop()

if node not in visited:

print(node) # Visit the node

visited.add(node)

for neighbor in graph[node]:

if neighbor not in visited:

stack.append(neighbor)

# Example graph (same as before)

graph = {

'A': ['B', 'C'],

'B': ['A', 'D'],

'C': ['A', 'D'],

'D': ['B', 'E'],

'E': ['D']

}

dfs(graph, 'A')

Here’s the output of the code above:

A

C

D

E

B

Just like BFS, we:

Track visited nodes with a set

Use a loop to process each node

Visit neighbors one by one

But here’s the important difference: DFS uses a stack, so it goes deep into one path until it can’t go further, then it backtracks and explores the next path. This makes it great for tasks like solving mazes or exploring all possibilities in a decision tree.

Wrapping Up Graph Traversal

Understanding how to traverse a graph is foundational to solving many real-world problems, from mapping routes to analyzing social networks. Whether you're using BFS to find the shortest path or DFS to explore deep relationships, choosing the right traversal method depends on the problem you're trying to solve.

Knight's Travails: A Real-World Graph Problem

To bring graphs to life, let’s start with a simple example.

Imagine you're playing chess, and your knight is stuck in one corner of the board. Let’s say you want to move it to a specific square to defend your queen. What’s the fewest number of moves it’ll take to get there?

This is a classic graph problem.

Each square on the chessboard can be represented as a node. If a knight can legally move from one square to another, there's an edge between them. The knight’s movement rules – those L-shaped hops – define the graph’s edges. So if you think about it, you're navigating a graph, trying to find the shortest path from one node (start square) to another (target square).

Let’s break it down.

Modeling the Board as a Graph

The chessboard is an 8x8 grid.

Each square is a node, identified by its coordinates

(x, y)where0 ≤ x < 8and0 ≤ y < 8.A knight has a maximum of 8 possible moves from any position (some may be out of bounds).

The goal is to build a graph where each node connects to all valid knight moves from that square.

BFS or DFS? Choosing the Right Tool

There are two traversal methods we discussed earlier, Breadth-First Search (BFS) and Depth-First Search (DFS). So, which one should we use to solve the Knight’s Travails problem?

Let’s think about what would happen if we used DFS.

DFS goes as deep as it can along one path before backtracking. So, if you use DFS to move the knight, it might follow a long, winding sequence of valid moves that eventually leads to the destination, say, in 7 moves.

But that doesn’t mean it’s the shortest path. The optimal path could have reached the target in just 3 or 4 moves, but DFS wouldn’t find that unless it happens to explore that exact path first.

Even worse, DFS doesn’t guarantee you’ll find the shortest path unless you exhaustively search every possibility and compare them, which is slow and inefficient for this kind of problem.

Now, here’s why BFS is a better fit.

BFS explores all positions the knight can reach in 1 move, then all positions reachable in 2 moves, then 3 moves, and so on. As soon as it finds the destination square, you can be sure it got there using the fewest possible steps, because it explores all shorter paths before any longer ones.

In short:

DFS might reach the destination eventually, but not efficiently, and not necessarily via the shortest path.

BFS guarantees that the path it returns is the shortest in terms of the number of moves.

That’s why, for problems like this, where minimum steps are the goal, BFS is the go-to approach.

Implementing Knight’s Travails with BFS

To model the knight’s traversal across the board, we’ll use a class called Square. This class will help us track:

The knight’s current position on the board (

x_coord,y_coord)A reference to its parent square, so we can reconstruct the shortest path once the destination is reached

Keep track of all valid next moves (its

children), which represent the squares the knight can legally move to from the current position

Here’s the initial class:

from collections import deque

# Class to represent a square on the chessboard

class Square:

def __init__(self, x_coord, y_coord, parent=None):

self.x_coord = x_coord

self.y_coord = y_coord

self.parent = parent

self.children = []

This setup is useful because we’re building a path tree: each move creates a child node, and we can trace our way back to the starting point using the parent.

How Does a Knight Move?

A knight in chess moves in an “L” shape, two steps in one direction and one step perpendicular to it. If the knight is at the center of an 8x8 chessboard, it can make up to 8 legal moves. These moves can be visualized as edges connecting one square (node) to others.

Here’s how we can represent and generate those moves:

from collections import deque

# Class to represent a square on the chessboard

class Square:

def __init__(self, x_coord, y_coord, parent=None):

self.x_coord = x_coord

self.y_coord = y_coord

self.parent = parent

self.children = []

def generate_legal_moves(self):

# All 8 possible knight moves (in L-shape)

row_moves = [-2, -1, 1, 2, 2, 1, -1, -2]

col_moves = [1, 2, 2, 1, -1, -2, -2, -1]

for dx, dy in zip(row_moves, col_moves):

nx, ny = self.x_coord + dx, self.y_coord + dy

# Only add valid board positions (0–7 for an 8x8 board)

if 0 <= nx < 8 and 0 <= ny < 8:

self.children.append(Square(nx, ny, self))

Finding the Shortest Path

Now that we have the Square class and the knight’s possible moves, we should implement BFS to find the shortest path from a starting square to a destination.

# BFS function to find the shortest path from start to end square

def knight_travails(start_coords, end_coords):

# Initialize the BFS queue with the starting square

start_x, start_y = start_coords

queue = deque([Square(start_x, start_y)])

# Set to track visited positions and prevent revisiting

visited = set()

end_coords = tuple(end_coords)

while queue:

current = queue.popleft()

coords = (current.x_coord, current.y_coord)

# If this square is the target, we've found the shortest path

if coords == end_coords:

return current

# Skip, if this position has already been visited

if coords in visited:

continue

visited.add(coords)

# Generate all legal knight moves from the current square

current.generate_legal_moves()

# Append children to queue

queue.extend(current.children)

def construct_path(start, end):

# Run BFS to get the final square

end_square = knight_travails(start, end)

path = []

# Trace back from the end square to the start using the parent links

while end_square:

path.append((end_square.x_coord, end_square.y_coord))

end_square = end_square.parent

# Reverse the path to show it from start to end

return path[::-1]

Once you’ve implemented the functions above, you can print the output like this:

print(construct_path([3, 4], [0, 1]))

This returns the shortest sequence of moves the knight must take to travel from [3, 4] to [0, 1]. Sample output:

[(3, 4), (2, 2), (0, 1)]

Each tuple represents a square on the chessboard that the knight visits. This is the shortest possible path the knight can take (from start to end square) – and thanks to how BFS works, we know for sure that no shorter path exists. That guarantee of optimality is what makes Breadth-First Search a perfect fit here.

Wrapping Up

From chessboards to road maps and airline routes, graphs are everywhere. They silently power much of the technology we rely on daily. Whether you're booking a flight, navigating a city, or getting a recommendation on your favorite app, graphs are often at work behind the scenes.

They allow you to model and solve complex real-world problems by connecting entities and exploring their relationships. So next time your Google Maps reroutes you, remember: graphs are the mechanism behind that magic. Once you start recognizing graphs, you start seeing the hidden structure behind apps, systems, and even games you use every day.

![[The AI Show Episode 151]: Anthropic CEO: AI Will Destroy 50% of Entry-Level Jobs, Veo 3’s Scary Lifelike Videos, Meta Aims to Fully Automate Ads & Perplexity’s Burning Cash](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20151%20cover.png)

![Z buffer problem in a 2.5D engine similar to monument valley [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/OlHwug81.jpg)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Kjetil_Kolbjornsrud_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Samsung teases Galaxy Z Fold 7 with an absolutely bizarre ‘Ultra experience’ [Video]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/galaxy-z-fold-7-teaser-1.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![iPhone 18 Pro, iPhone Fold to Feature New A20 Chip With Advanced WMCM Packaging [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97494/97494/97494-1280.jpg)