Inside the effort to tally AI’s energy appetite

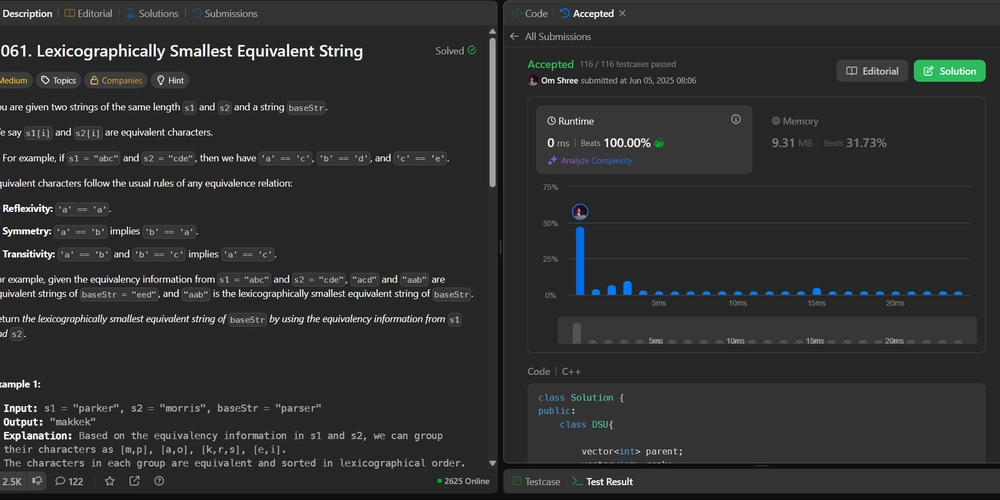

After working on it for months, my colleague Casey Crownhart and I finally saw our story on AI’s energy and emissions burden go live last week. The initial goal sounded simple: Calculate how much energy is used each time we interact with a chatbot, and then tally that up to understand why everyone from leaders…

After working on it for months, my colleague Casey Crownhart and I finally saw our story on AI’s energy and emissions burden go live last week.

The initial goal sounded simple: Calculate how much energy is used each time we interact with a chatbot, and then tally that up to understand why everyone from leaders of AI companies to officials at the White House wants to harness unprecedented levels of electricity to power AI and reshape our energy grids in the process.

It was, of course, not so simple. After speaking with dozens of researchers, we realized that the common understanding of AI’s energy appetite is full of holes. I encourage you to read the full story, which has some incredible graphics to help you understand everything from the energy used in a single query right up to what AI will require just three years from now (enough electricity to power 22% of US households, it turns out). But here are three takeaways I have after the project.

AI is in its infancy

We focused on measuring the energy requirements that go into using a chatbot, generating an image, and creating a video with AI. But these three uses are relatively small-scale compared with where AI is headed next.

Lots of AI companies are building reasoning models, which “think” for longer and use more energy. They’re building hardware devices, perhaps like the one Jony Ive has been working on (which OpenAI just acquired for $6.5 billion), that have AI constantly humming along in the background of our conversations. They’re designing agents and digital clones of us to act on our behalf. All these trends point to a more energy-intensive future (which, again, helps explain why OpenAI and others are spending such inconceivable amounts of money on energy).

But the fact that AI is in its infancy raises another point. The models, chips, and cooling methods behind this AI revolution could all grow more efficient over time, as my colleague Will Douglas Heaven explains. This future isn’t predetermined.

AI video is on another level

When we tested the energy demands of various models, we found the energy required to produce even a low-quality, five-second video to be pretty shocking: It was 42,000 times more than the amount needed for a chatbot answer a question about a recipe, and enough to power a microwave for over an hour. If there’s one type of AI whose energy appetite should worry you, it’s this one.

Soon after we published, Google debuted the latest iteration of its Veo model. People quickly created compilations of the most impressive clips (this one being the most shocking to me). Something we point out in the story is that Google (as well as OpenAI, which has its own video generator, Sora) denied our request for specific numbers on the energy their AI models use. Nonetheless, our reporting suggests it’s very likely that high-definition video models like Veo and Sora are much larger, and much more energy-demanding, than the models we tested.

I think the key to whether the use of AI video will produce indefensible clouds of emissions in the near future will be how it’s used, and how it’s priced. The example I linked shows a bunch of TikTok-style content, and I predict that if creating AI video is cheap enough, social video sites will be inundated with this type of content.

There are more important questions than your own individual footprint

We expected that a lot of readers would understandably think about this story in terms of their own individual footprint, wondering whether their AI usage is contributing to the climate crisis. Don’t panic: It’s likely that asking a chatbot for help with a travel plan does not meaningfully increase your carbon footprint. Video generation might. But after reporting on this for months, I think there are more important questions.

Consider, for example, the water being drained from aquifers in Nevada, the country’s driest state, to power data centers that are drawn to the area by tax incentives and easy permitting processes, as detailed in an incredible story by James Temple. Or look at how Meta’s largest data center project, in Louisiana, is relying on natural gas despite industry promises to use clean energy, per a story by David Rotman. Or the fact that nuclear energy is not the silver bullet that AI companies often make it out to be.

There are global forces shaping how much energy AI companies are able to access and what types of sources will provide it. There is also very little transparency from leading AI companies on their current and future energy demands, even while they’re asking for public support for these plans. Pondering your individual footprint can be a good thing to do, provided you remember that it’s not so much your footprint as these other factors that are keeping climate researchers and energy experts we spoke to up at night.

This story originally appeared in The Algorithm, our weekly newsletter on AI. To get stories like this in your inbox first, sign up here.

![[The AI Show Episode 151]: Anthropic CEO: AI Will Destroy 50% of Entry-Level Jobs, Veo 3’s Scary Lifelike Videos, Meta Aims to Fully Automate Ads & Perplexity’s Burning Cash](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20151%20cover.png)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![Epic Games: Apple’s attempt to pause App Store antitrust order fails [U]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/05/epic-games-app-store.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple AI Launch in China Delayed Amid Approval Roadblocks and Trade Tensions [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97500/97500/97500-640.jpg)

![[UPDATED] New Android Trojan Can Fake Contacts to Scam You — Meet Crocodilus](https://www.androidheadlines.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Android-malware-image-1.jpg)

![T-Mobile may be misleading customers into spending more with new switch offer [UPDATED]](https://m-cdn.phonearena.com/images/article/171029-two/T-Mobile-may-be-misleading-customers-into-spending-more-with-new-switch-offer-UPDATED.jpg?#)