Sparks fly: Seattle-area fusion startup rivals debate path to commercial power

REDMOND, Wash. — The conversation got a little heated at a Seattle-area conference Tuesday when three companies vying to commercialize fusion power took the stage. The Pacific Northwest is a hub for fusion innovation, and Washington is home to Helion Energy, Zap Energy and Avalanche Energy, among others. It’s a small and generally collegial cluster, but representatives from the trio of companies took some swipes at each other at the Technology Alliance event as they laid out their ambitions for commercial success. With more than $1 billion from investors, Helion has set the most aggressive timelines for deploying its technology.… Read More

REDMOND, Wash. — The conversation got a little heated at a Seattle-area conference Tuesday when three companies vying to commercialize fusion power took the stage.

The Pacific Northwest is a hub for fusion innovation, and Washington is home to Helion Energy, Zap Energy and Avalanche Energy, among others. It’s a small and generally collegial cluster, but representatives from the trio of companies took some swipes at each other at the Technology Alliance event as they laid out their ambitions for commercial success.

With more than $1 billion from investors, Helion has set the most aggressive timelines for deploying its technology. The Everett company aims to build and operate what could be the world’s first fusion power plant — a 50-megawatt facility whose electricity is earmarked for Microsoft and is supposed to come online in 2028.

“We’re focused on producing electricity and breaking down all of the barriers to make that happen in this decade,” said Anthony Pancotti, co-founder and head of R&D for Helion.

Ben Levitt, the head of R&D for Zap, said the field is progressing and fusion is definitely coming — but on stage at the Seattle Investor Summit+Showcase, he questioned Helion’s target.

“I don’t see a commercial application in the next few years happening,” Levitt said. “There is a lot of complicated science and engineering still to be discovered and to be applied.”

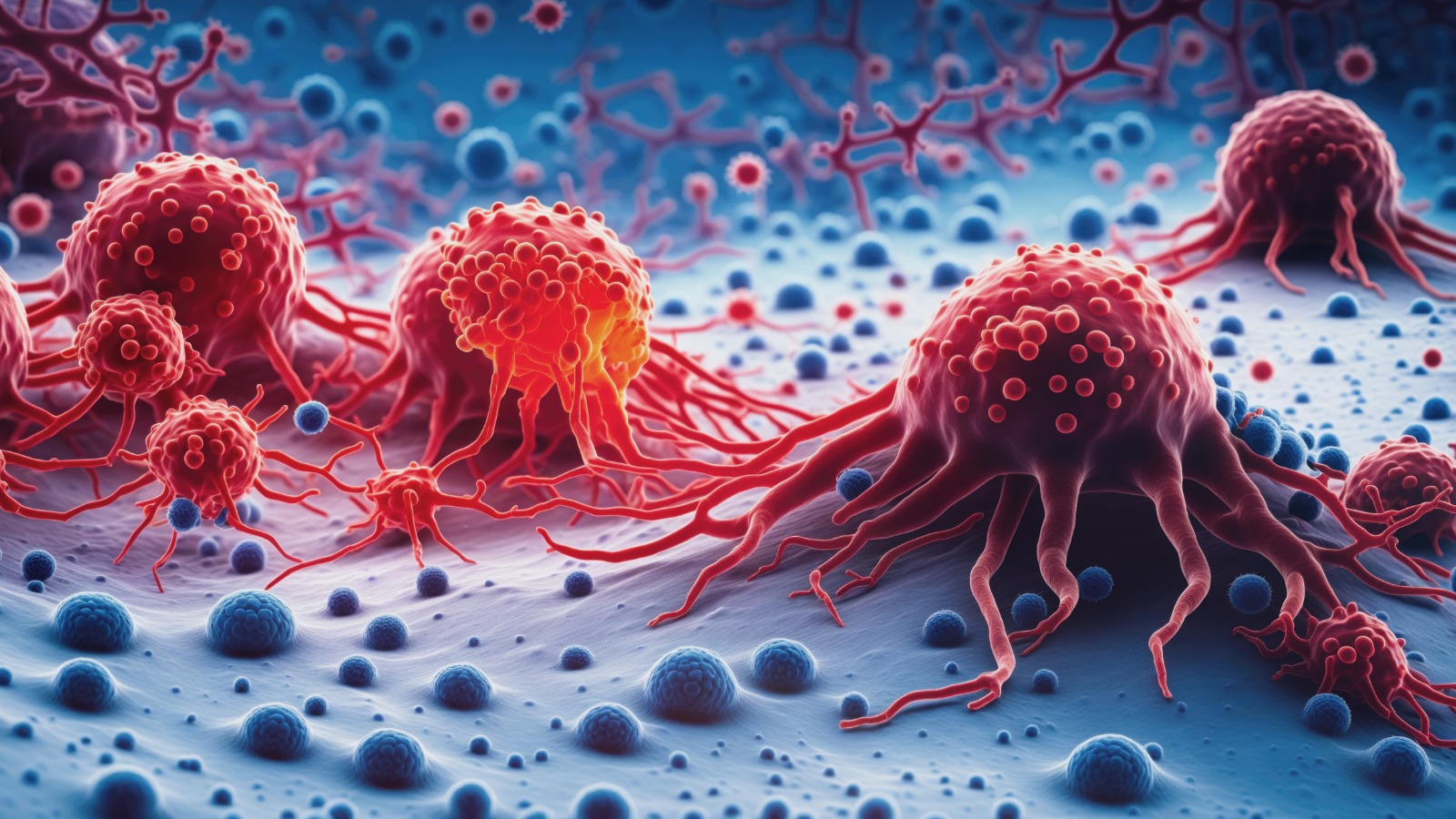

Fusion, which powers the sun and the stars, requires super hot, super high-pressure conditions sustained over time. The goal for the companies is to engineer a technology that generates and captures more energy from smashing atoms together than is needed to produce the reactions — a target known as “Q greater than 1.”

Later this decade and into the next, “you’ll see small scale, not necessarily profitable fusion,” Levitt predicted. “But you will see fusion demonstrations with greater output energy than input.”

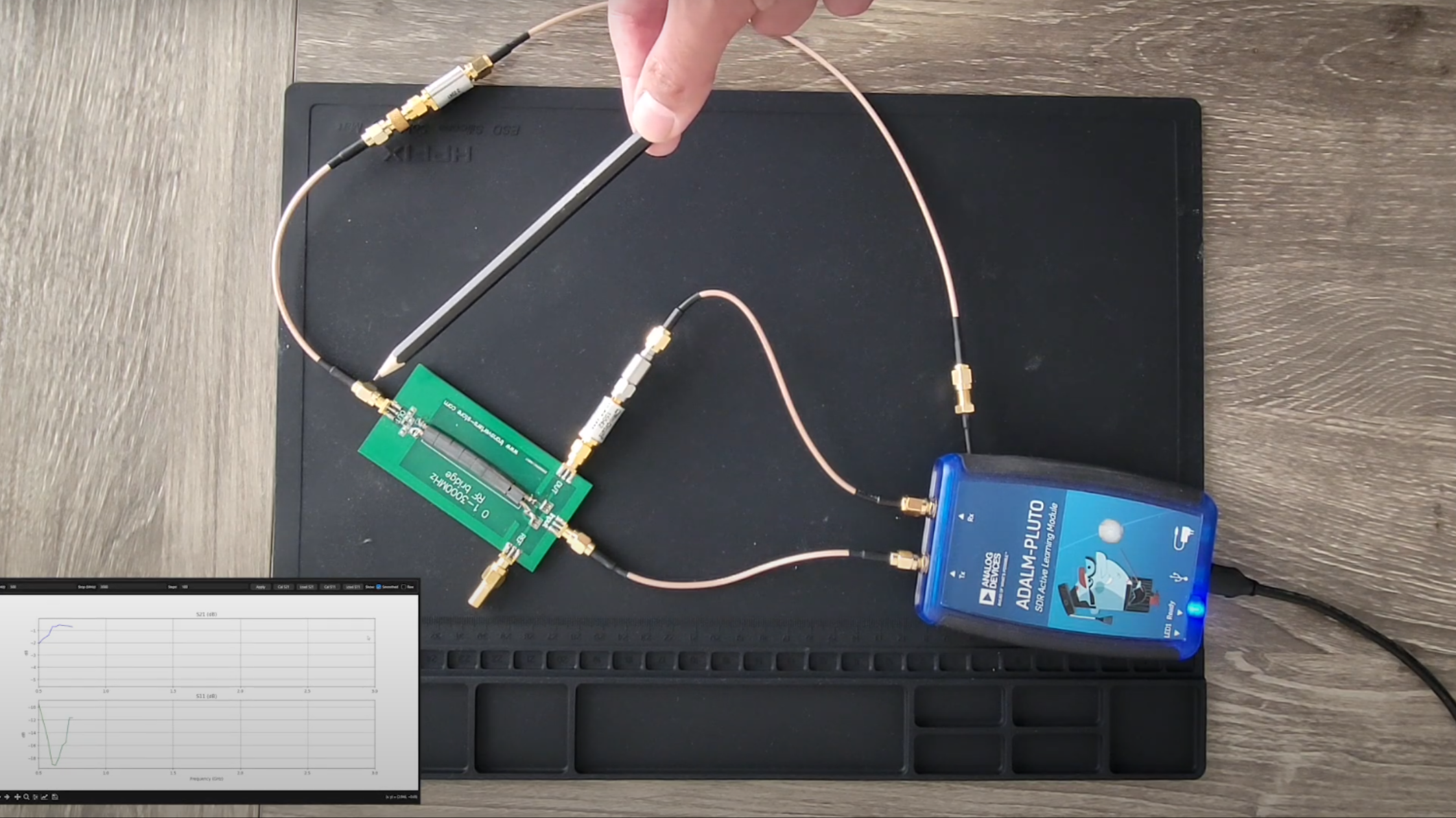

Helion is currently testing its Polaris reactor, a seventh-generation prototype that will be the same size as the planned commercial reactor. The sector is attracting interest from tech companies desperate for clean energy for their power-hungry data centers.

Zap, which is located in Everett a short distance from Helion, hasn’t set an expected date for the commercialization of its technology. The company is experimenting with its FuZE-Q fusion device and has built its Century system, a prototype including components beyond the reactor that will be needed to generate power for the grid.

For Brian Riordan, co-founder and chief operating officer of Seattle’s Avalanche, the question comes down to economics.

“Ultimately, I don’t think the first [company] to ‘Q greater than 1’ is going to matter,” he said. “What’s going to matter is who can make it economical. The first car company in the U.S. was like Duryea Power Wagon Corp. or something, and nobody remembers because they didn’t make it cheap enough.” (Riordan was close — it was Duryea Motor Wagon Company.)

Avalanche is aiming for Q equals 1, a lower bar to clear, within about two years, Riordan said, but that would be in a prototype, not a commercial device.

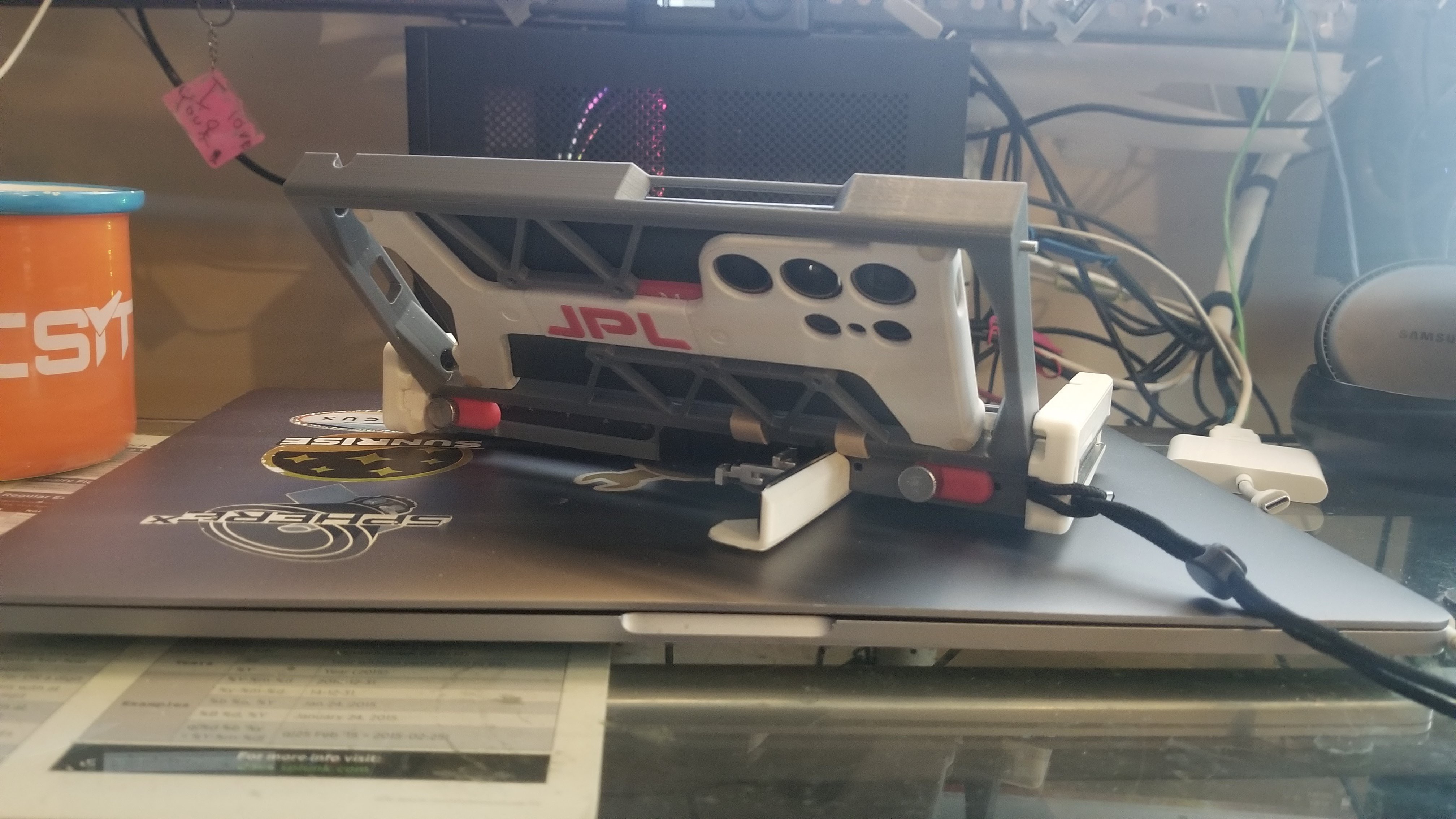

In 2022, Avalanche won a Pentagon contract from the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) to develop a fusion device called the Orbitron for space propulsion and power generation. Its reactor system is among the compact — smaller than one of the event’s conference tables, Riordan said.

While the debate over timing and targets will be settled in coming years, the three panelists agreed that the most important thing is someone cracks the fusion challenge and unlocks this potentially vast source of clean energy.

“Good luck to everybody,” Levitt said. “If fusion wins, we’re all winners. We want to be the first, of course. But you know, any winner is a winner for humanity.”

![[The AI Show Episode 151]: Anthropic CEO: AI Will Destroy 50% of Entry-Level Jobs, Veo 3’s Scary Lifelike Videos, Meta Aims to Fully Automate Ads & Perplexity’s Burning Cash](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20151%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] FileJump 2TB Cloud Storage: Lifetime Subscription (85% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Apple Shares Official Trailer for 'The Wild Ones' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97515/97515/97515-640.jpg)