30 years ago, ‘Hackers’ and ‘The Net’ predicted the possibilities—and horrors—of internet life

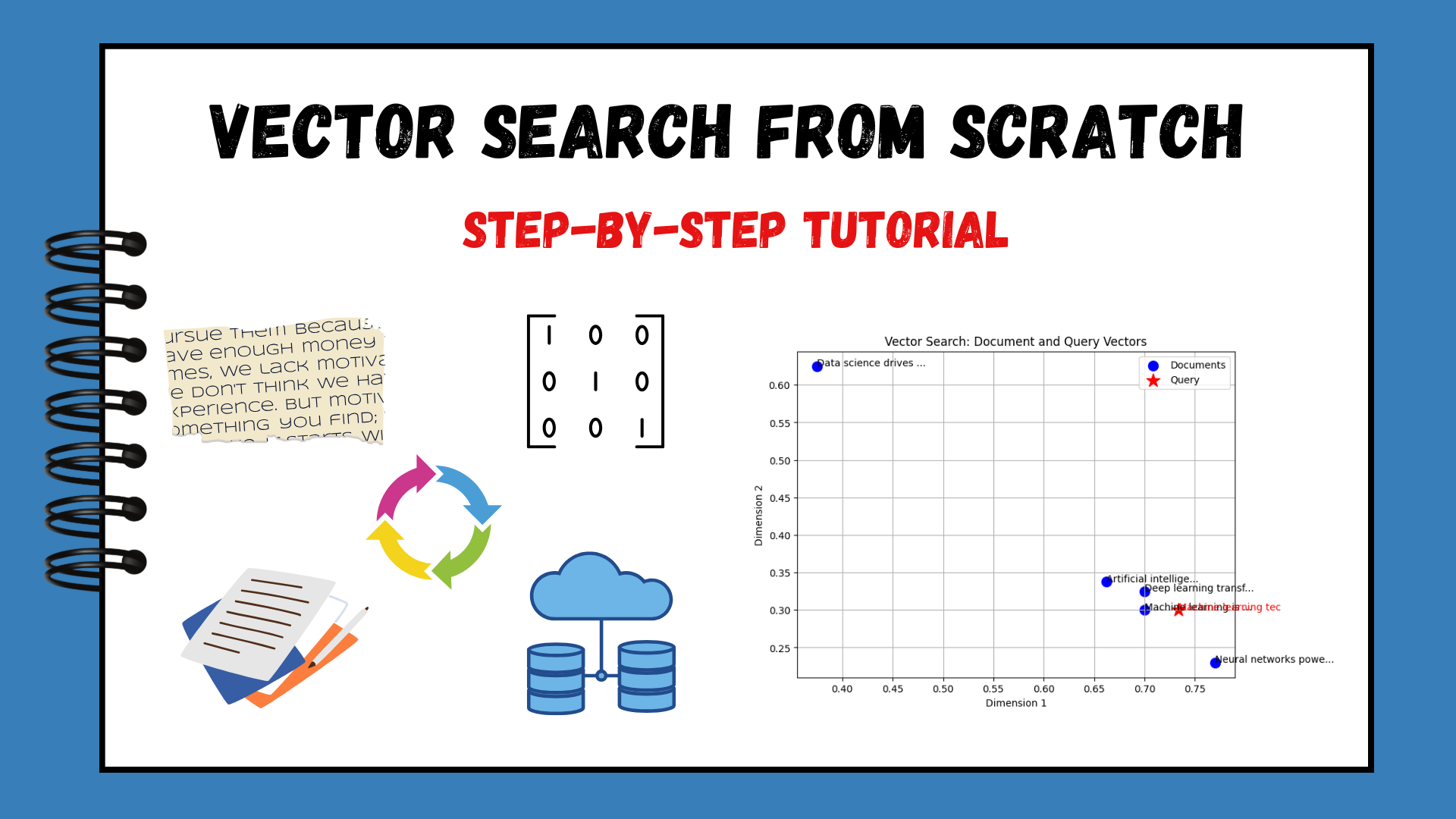

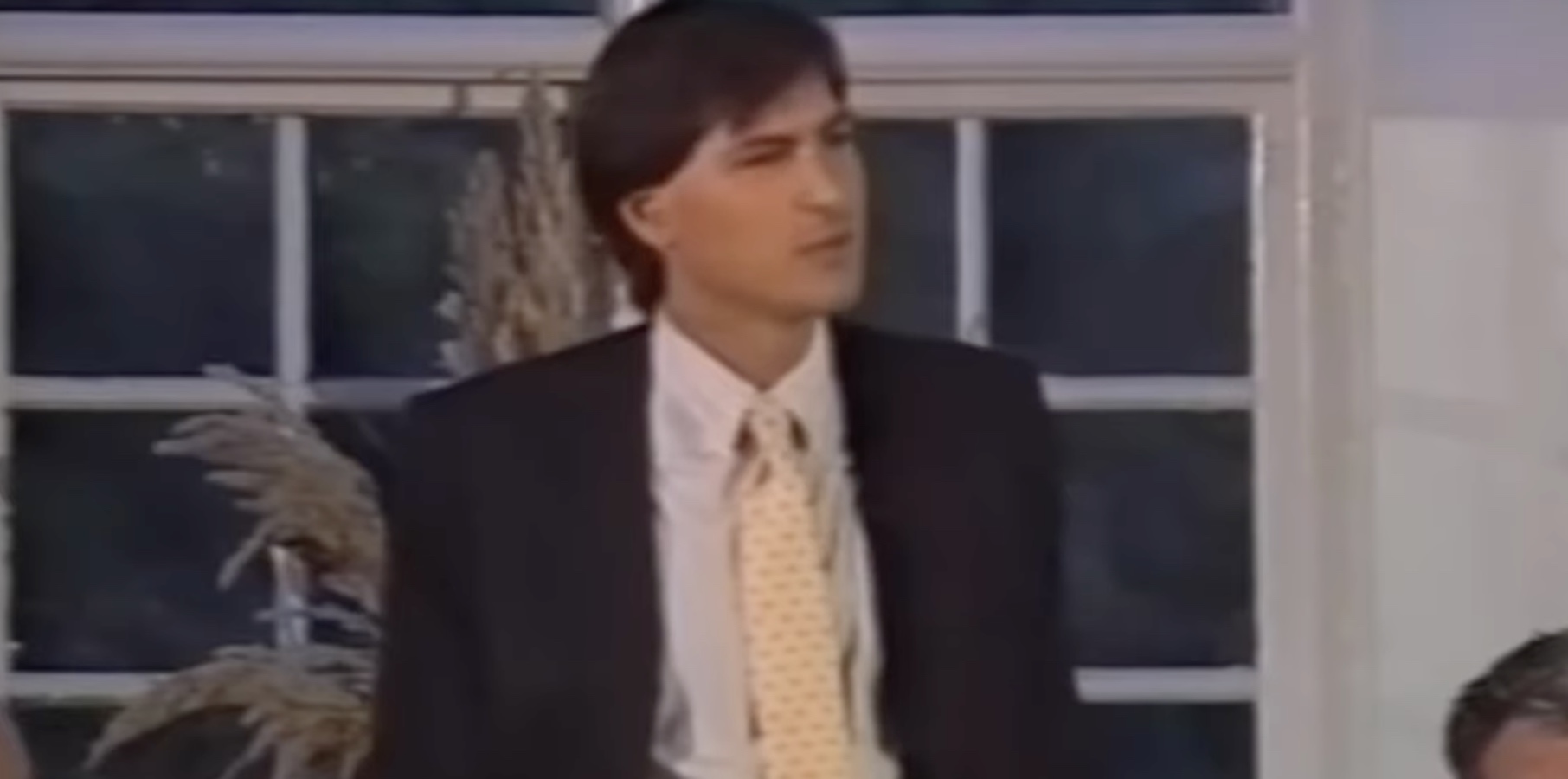

Getting an email in the mid-’90s was kind of an event—somewhere between hearing an unexpected knock at the door and walking into your own surprise party. The white-hot novelty of electronic mail is preserved in amber by a ridiculous 1994 film: reverse sexual-harassment thriller Disclosure. It opens with a little girl perusing what was once known as a “family computer” before casually shouting, “Daaaad, you got an email!” Her announcement is as much for the benefit of 1994 viewers as it is for Michael Douglas’s character, an executive in the Seattle tech scene, letting them know they’re witnessing their imminent future. [Photo: MGM] At that point, the majority of Americans had never seen an email. According to a contemporary Pew Research poll, 42% had never even heard of the internet. Still, the early ’90s thrummed with the propulsive drum line of digital revolution. The internet had existed in more esoteric forms for ages, but now America Online had terraformed it for normies, and Netscape’s landmark IPO in 1995 began fueling the frenzy of the dot-com boom. Things changed fast, and The Net and Hackers dragged online culture center stage. Released as summer bookends, The Net stars Sandra Bullock as a tech worker whose identity is stolen, while Hackers, featuring Angelina Jolie in her first major role, follows a squad of elite high school coders as they get caught up in a corporate conspiracy. Looking back now on the flag-planting internet movies of 1995, it’s incredible how well they predicted the possibilities and horrors on the horizon. Fast Company talked to the filmmakers behind both about all that’s changed in the 30 years since. [Photo: Sony Pictures] Neither ’90s movie was a blockbuster, exactly. The Net proved a modest success, earning $110 million worldwide and spawning a short-lived TV adaptation a few years later, while Hackers flopped, making back less than half of its reported $20 million budget. Both gained long tails of notoriety and cult-classic status, however, in part for having depicted the internet on-screen at the precise moment most filmgoers were discovering it at home. The concept of connectivity had, of course, graced movie theaters before. Matthew Broderick plays a crafty teen who tweaks his high school computer system from home in both 1983’s WarGames and again three years later in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. A ragtag team of techies spends the entire run time of 1992’s hacking romp, Sneakers, spelunking in a shadow realm of digital information. As technology rapidly evolved, though, and ’90s news anchors began talking about chat rooms and using terms like cyberspace, it had to evolve in pop culture as well. [Photo: TriStar Pictures] Several studio releases from 1995 were lumped together as “internet movies,” with critics cross-referencing them in reviews. Among them were Virtuosity, in which Russell Crowe plays a computer-generated killer, and Johnny Mnemonic, which is mostly remembered as the cyberpunk action flick Keanu Reeves made before The Matrix. Both are set in the speculative sci-fi future—1999 for Virtuosity, 2021 for Johnny Mnemonic—while paranoid thriller The Net and teen comedy Hackers are dialed into reality on the ground and online. “At that point, no one had yet to really make a movie that was anywhere in that world,” says Jeff Kleeman, the executive producer who oversaw the development of Hackers. “Part of the reason I was excited about it was I felt like, for some reason, nobody is doing this. And I just thought, somebody ultimately is going to do this and I hope it’s me.” “It was slow, and then very fast” Before making Hackers, Kleeman didn’t quite understand all the hype about the internet. He could easily grasp its significance for global businesses and governments, but on a personal level, he hadn’t found many use cases. Still, he had absolute faith in the allure of a project about computer-savvy teenagers making digital mayhem. As he learned from Secret Service agents while researching the movie, teenagers at the time understood the internet better than anybody. Kleeman shepherded Hackers practically from its inception. It started when a friend, an artist named Rafael Moreau, confided that he’d lately been tagging along with an elite hacking crew known as the Legion of Doom, and he was thinking of writing a movie based on them. Kleeman was skeptical (film executives generally do not want to field pitches from novice writer pals), but he agreed to take a look at the screenplay, should one ever materialize. He was blown away by what Moreau eventually delivered. The first draft of Hackers had a technical authenticity absorbed from its primary sources, and it pulsed with kinetic energy. Equally impressive, the dialogue read like it came from actual human teenagers. Kleeman first attempted to put the film into production at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope before succeeding years later at United Artists. Meanwhile,

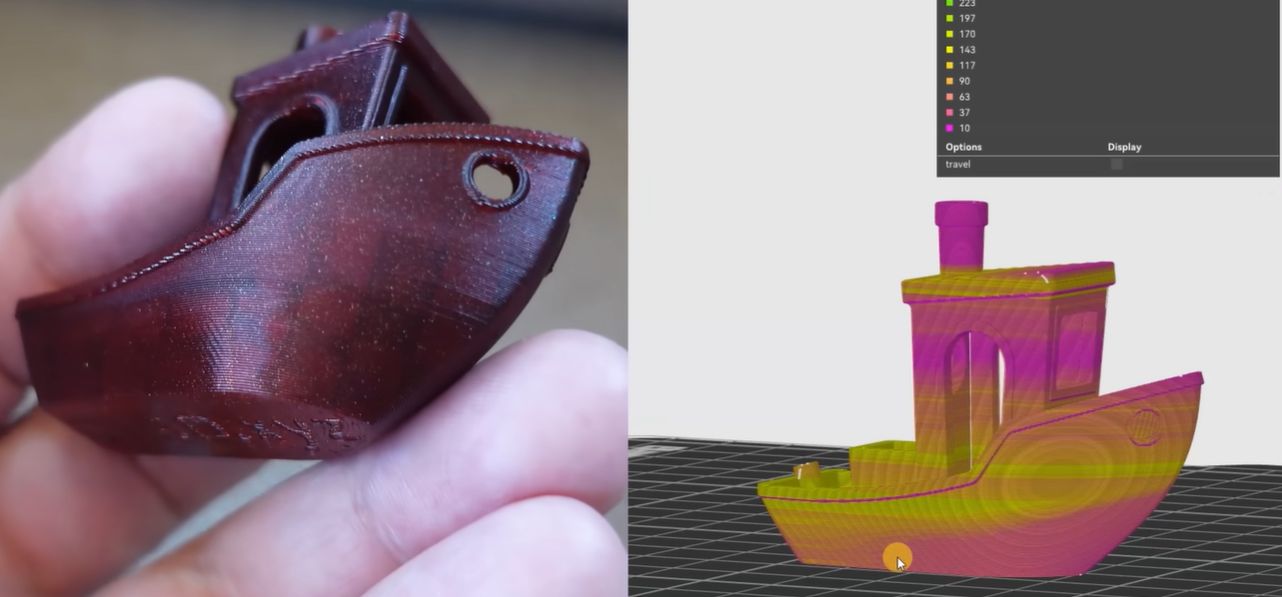

Getting an email in the mid-’90s was kind of an event—somewhere between hearing an unexpected knock at the door and walking into your own surprise party. The white-hot novelty of electronic mail is preserved in amber by a ridiculous 1994 film: reverse sexual-harassment thriller Disclosure. It opens with a little girl perusing what was once known as a “family computer” before casually shouting, “Daaaad, you got an email!” Her announcement is as much for the benefit of 1994 viewers as it is for Michael Douglas’s character, an executive in the Seattle tech scene, letting them know they’re witnessing their imminent future.

At that point, the majority of Americans had never seen an email. According to a contemporary Pew Research poll, 42% had never even heard of the internet. Still, the early ’90s thrummed with the propulsive drum line of digital revolution. The internet had existed in more esoteric forms for ages, but now America Online had terraformed it for normies, and Netscape’s landmark IPO in 1995 began fueling the frenzy of the dot-com boom. Things changed fast, and The Net and Hackers dragged online culture center stage.

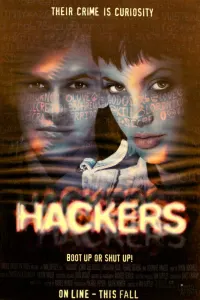

Released as summer bookends, The Net stars Sandra Bullock as a tech worker whose identity is stolen, while Hackers, featuring Angelina Jolie in her first major role, follows a squad of elite high school coders as they get caught up in a corporate conspiracy. Looking back now on the flag-planting internet movies of 1995, it’s incredible how well they predicted the possibilities and horrors on the horizon. Fast Company talked to the filmmakers behind both about all that’s changed in the 30 years since.

Neither ’90s movie was a blockbuster, exactly. The Net proved a modest success, earning $110 million worldwide and spawning a short-lived TV adaptation a few years later, while Hackers flopped, making back less than half of its reported $20 million budget. Both gained long tails of notoriety and cult-classic status, however, in part for having depicted the internet on-screen at the precise moment most filmgoers were discovering it at home.

The concept of connectivity had, of course, graced movie theaters before. Matthew Broderick plays a crafty teen who tweaks his high school computer system from home in both 1983’s WarGames and again three years later in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. A ragtag team of techies spends the entire run time of 1992’s hacking romp, Sneakers, spelunking in a shadow realm of digital information. As technology rapidly evolved, though, and ’90s news anchors began talking about chat rooms and using terms like cyberspace, it had to evolve in pop culture as well.

Several studio releases from 1995 were lumped together as “internet movies,” with critics cross-referencing them in reviews. Among them were Virtuosity, in which Russell Crowe plays a computer-generated killer, and Johnny Mnemonic, which is mostly remembered as the cyberpunk action flick Keanu Reeves made before The Matrix. Both are set in the speculative sci-fi future—1999 for Virtuosity, 2021 for Johnny Mnemonic—while paranoid thriller The Net and teen comedy Hackers are dialed into reality on the ground and online.

“At that point, no one had yet to really make a movie that was anywhere in that world,” says Jeff Kleeman, the executive producer who oversaw the development of Hackers. “Part of the reason I was excited about it was I felt like, for some reason, nobody is doing this. And I just thought, somebody ultimately is going to do this and I hope it’s me.”

“It was slow, and then very fast”

Before making Hackers, Kleeman didn’t quite understand all the hype about the internet. He could easily grasp its significance for global businesses and governments, but on a personal level, he hadn’t found many use cases. Still, he had absolute faith in the allure of a project about computer-savvy teenagers making digital mayhem. As he learned from Secret Service agents while researching the movie, teenagers at the time understood the internet better than anybody.

Kleeman shepherded Hackers practically from its inception. It started when a friend, an artist named Rafael Moreau, confided that he’d lately been tagging along with an elite hacking crew known as the Legion of Doom, and he was thinking of writing a movie based on them. Kleeman was skeptical (film executives generally do not want to field pitches from novice writer pals), but he agreed to take a look at the screenplay, should one ever materialize. He was blown away by what Moreau eventually delivered.

The first draft of Hackers had a technical authenticity absorbed from its primary sources, and it pulsed with kinetic energy. Equally impressive, the dialogue read like it came from actual human teenagers. Kleeman first attempted to put the film into production at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope before succeeding years later at United Artists.

Meanwhile, the film that would come to be called The Net originally had very little to do with going online. It started instead as a project about résumé-tampering.

Producer Irwin Winkler had read a buzzy spec script called The Game, which David Fincher would go on to direct, and wanted to meet its writers. The project he had in mind for them centered on a woman who hires a hacker to fake her résumé so she can land a job at a major advertising firm, only to end up with the hacker becoming obsessed with her. (“Fatal Attraction with some glimmerings of high-tech in the background” is how one of The Net’s writers, Mike Ferris, describes it.)

The in-demand duo took on the gig, executives approved their outline, and they churned out a draft. Nobody involved with the project was impressed by what they turned in, including the scribes themselves. By the time they embarked on the next draft, though, writer John Brancato had read a book on the topic of identity theft, and it sparked some ideas.

“It was a book about the possibility of a digital shadow and how the world could fuck with it,” Brancato says. “And that seemed like an interesting thing.”

The writing pair seized on a scene that took place near the end of their first draft—when the hacker starts erasing the protagonist’s credit history and banking data—and decided to make it the engine of the movie. The story would now focus on a computer expert whose entire life is being expunged online, forcing her to figure out why and reclaim her identity. The executives were thrilled. Their résumé-tampering project had morphed into a movie steeped in the technology that was defining the era in real time.

“During production is when more of the hype about the internet really started rolling out,” Brancato says. “The awareness of it was slow, and then very fast.”

The most infamous delivery order in film history

While Disclosure trumpeted the glorious future of normalized email the previous year, Hackers and The Net showed ’90s viewers what else might be possible online.

During an early scene in Hackers, Jonny Lee Miller’s character, Dade Murphy, digitally breaks into a TV station, preempting a right-wing talk show to put on an episode of The Outer Limits. Through a 2025 lens, it seems bizarre that he’d even think to do such a thing. Anyone wanting to watch The Outer Limits, or any TV show ever, can now easily do so with minimal keystrokes. To the average viewer in the ’90s, however, what Murphy does is essentially sorcery.

The Net has some similarly dated ’90s tech-flexing. Its opening moments follow systems analyst Angela Bennett, played by Bullock, as she goes about a flurry of online activity. Viewers watch her talk to some pals in a chat room (ooh!), purchase plane tickets right from her computer (ahh!), and in perhaps the most infamous food delivery in film history, order pizza online.

Although it was considered state-of-the-art in a pre-Domino’s Pizza Tracker era, this scene quickly curdles into kitsch. “I’m sure any kid watching now would be like, ‘Why are we looking at that?’” Ferris says of the moment.

Other aspects of the film’s tech turned out to be more prescient. Bullock’s character works on her laptop at the beach, prefiguring the remote-work era—even if she does wonder aloud, “Where can I hook up my modem?” (Wi-Fi would not be invented for another three years.) Dial-up internet took 30 seconds to connect in 1995, but Bullock’s character logs on at a speed much closer to present-day broadband internet. The quickness was meant to spare viewers from the full-length screeching sound of modems meeting up, according to Brancato, but some viewers still complained about the lack of realism.

One thing that’s aged well about both movies is what isn’t in them: virtual reality.

At the time, hype around VR ran parallel to internet evangelism in the mid-’90s. Both technologies appeared on the verge of becoming equally ubiquitous in the American future. Hollywood had already called its shot, making VR central to the plot of several sci-fi films, including 1992’s The Lawnmower Man, 1994’s Brainscan, and 1995’s Strange Days and Virtuosity. The worst offender may have been the more down-to-earth Disclosure, which somehow went all in on the idea of office workers donning VR headsets to find files within their computers. To their credit, The Net avoids VR entirely while only the try-hard villain in Hackers, played by Fisher Stevens, is briefly glimpsed wearing those goggles—and he’s meant to look like a huge dork while doing so.

“Our whole lives are on the computer”

Beyond showcasing some technological possibilities newly on offer, the early internet movies of the ’90s also flicked at the broader societal shifts they represented—for better and worse.

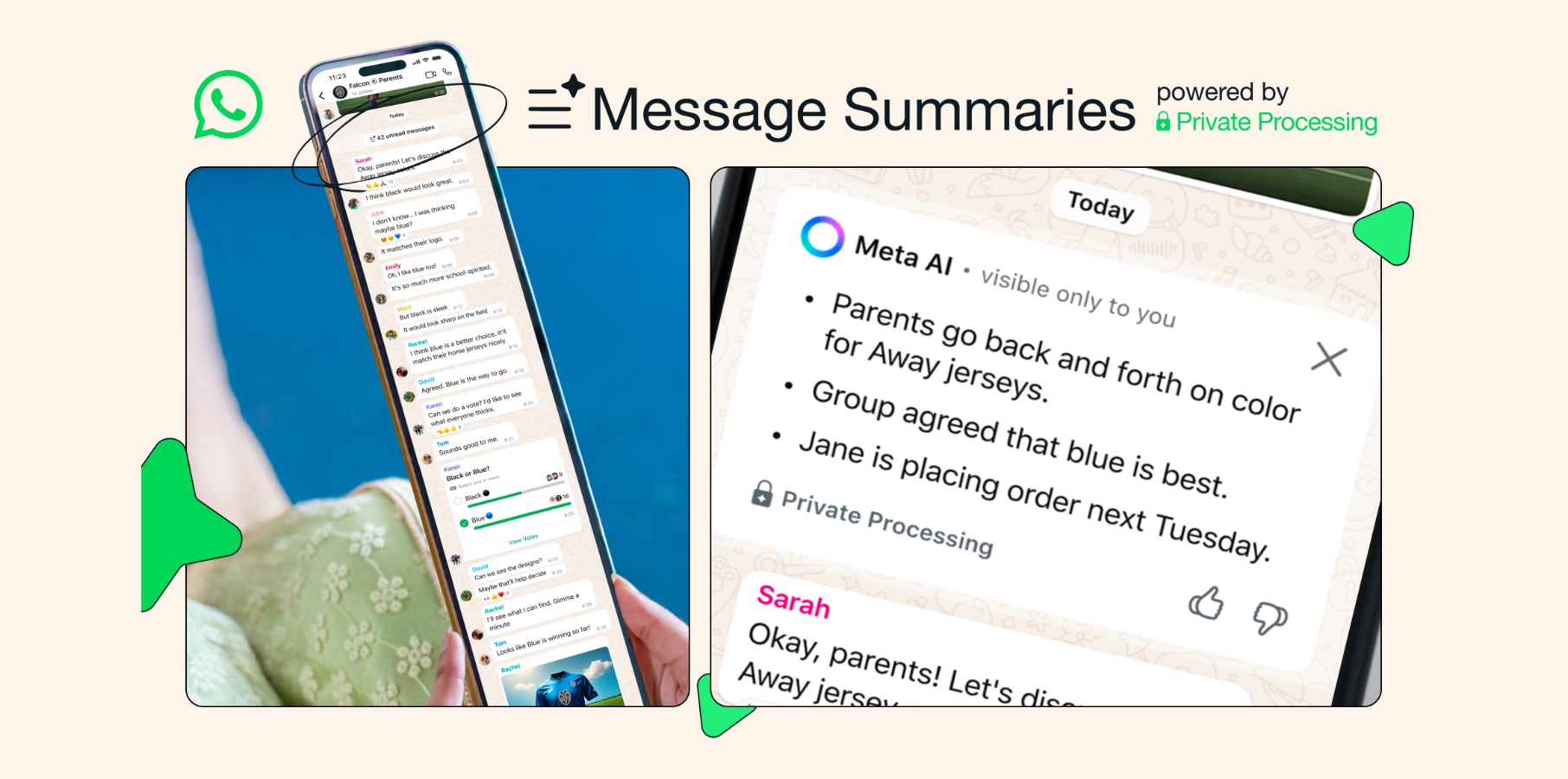

“Our whole lives are on the computer,” Bullock’s character says at one point in The Net. It might as well have been the tagline for the film. Although it’s since become self-evident, nascent online dwellers of the ’90s may not have understood just how much sensitive data about them was floating around in the ether, let alone the fluid nature of that data and the real-world consequences attached to changing it.

Bullock’s character spends a large chunk of the movie trying to convince various authority figures she’s actually systems analyst Angela Bennett, even though all online records now indicate she’s hardened criminal Ruth Marx. This real-world editing is a far cry from Ferris Bueller changing the number of school absences he’s incurred in a semester. It might be considered almost tame by today’s standards, though, since it affects only one person.

The Net seems to anticipate a catastrophic problem that has only metastasized over the past decade: the degradation of objective truth. In 2025, between AI deepfakes and other forms of digital disinformation, it’s now harder than ever to distinguish what’s real from what isn’t.

“That’s what was so scary about the entire thing, even back then,” Brancato says. “The more you consign reality to this machine, the more manipulable it is.”

Hackers, however, demonstrated the bright side of manipulating reality on- and offline.

Although the film never addresses their sexuality explicitly, Matthew Lillard’s character, who goes by Cereal (as in Cereal Killer), and Renoly Santiago’s character, who answers to Phreak, are both stylized with a queer-coded, gender-fluid aesthetic. Lillard’s look—long, braided pigtails, eye makeup, and tight crop tops—was especially audacious for a male high school student in a mainstream movie from 1995. As Kleeman confirms, these style choices are meant to underline the liberating quality of the internet; the way it thrust its users into a choose-your-own-adventure mode of identity.

“For the first time that I know of, in the history of humanity, if you were a high school kid, you could actually have a second life online,” he says. “And what you did with that identity in terms of gender, in terms of attitude or personality, was completely up for grabs.”

As for the paranoia around data privacy radiating off both ’90s films, it now seems nearly as quaint as ordering pizza from Pizza.net.

“I would’ve been up in arms 10 or 15 years ago about Amazon or Apple listening through our devices,” Ferris says. “And now everyone’s just like, ‘Well, yeah, sure they do. I mean, what are you gonna do? Throw away your phone? Throw away your computer?’ I’m not as outraged about that stuff as I feel like I should be.”

The escape you can’t escape

As much as the earliest internet movies seemed to peer into the future, the iPhone’s emergence is what rendered them hopelessly stuck in the past.

Hackers and The Net present computers as rabbit holes, transporting users into a weird, wild online wonderland. Everything changed once a tiny, high-speed computer was suddenly within arm’s reach at all waking hours. The internet ceased being a mysterious place people sometimes visited, and instead became an omnipresent layer on top of the real world, no entry required.

As much as Hackers made the internet feel dynamic—depicting it as a vivid cityscape of circuitry, with skyscraper-like database towers—it was still a world that needed to be approached from a static location. Like all early internet movies, Hackers and The Net now suffer from the fact that a lot of their action features a person seated at a computer, typing really hard. Once most people had smartphones, filmmakers started to simply overlay a user interface on-screen. Characters could now move around physically as their online activity moved the plot forward.

Of course, the invention of the iPhone may have hurt all movies, not just the retro internet ones from the ’90s. Once most modern movie characters had instant access to all information in recorded history, it became too easy for them to solve juicy cinematic problems. They now either have to lose Wi-Fi access somehow, or go back in time. Perhaps the reason directors like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and Paul Thomas Anderson seem to make only period pieces these days is so they can create movies devoid of the ever-present internet.

While going online was once a tantalizing escape from reality, a lot of people now seem to fantasize instead about escaping from the internet. In that sense, The Net did accurately predict the future. It ends with Sandra Bullock literally going outside and touching grass.

![[The AI Show Episode 156]: AI Answers - Data Privacy, AI Roadmaps, Regulated Industries, Selling AI to the C-Suite & Change Management](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20156%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] 1min.AI: Lifetime Subscription (82% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

_incamerastock_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Nothing Phone (3) has a 50MP ‘periscope’ telephoto lens – here are the first samples [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/nothing-phone-3-telephoto.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)