The Design of Trust, or How a Game Designer Manipulates .

I. Preface: «Guiding the blind (or pretending to be one?)» Do you enjoy being mistrusted? Think back to that feeling when you tackle a new, intriguing task — whether it’s assembling a complex model, solving a puzzle, or finding your way along an unfamiliar route—and someone hovers over your shoulder. They prompt every step, point out the obvious, never give you a chance to trip, to ponder, to find the solution on your own. Annoying, isn’t it? It feels as though they take you for a fool who can’t put two and two together without outside help. Perhaps I don’t understand something about life. Maybe today’s world really does demand maximum safety and the minimization of any effort or risk. But when I look at the game industry — especially its mainstream sector — I see a trend I’d call design born of fear: fear of losing the player, fear of seeming too difficult, fear of being rated poorly for “obscurity.” And that fear breeds a monster: hyper-protection. Games that should be spaces for exploration, experimentation, and triumph become interactive manuals where every step is predetermined, every puzzle comes with an obvious answer, and any hint of autonomy is immediately stifled by a pop-up hint or a bold map marker. Here begins my personal designer’s irony — almost a tragedy. We, the creators of games, tirelessly declare at conferences, in interviews, and in books that games are a unique form of interactive art. We speak of deep dialogue with the player, of crafting a one-of-a-kind personal experience through interaction. Then we return to our design docs and, with our own hands, strangle that very artistic potential. Exploration, interpretation, self-reflection — the very essence of interactivity and art — are sacrificed to mechanical instruction-following. We turn the player from an explorer into a courier chasing GPS markers. Imagine a director who, before a film screening, hands every viewer a detailed synopsis explaining every metaphor and even allows the audience to ignore theater etiquette and chatter loudly throughout… It’s as if we panic that the player “won’t get it,” so we drape the interactive canvas with layers of hints, killing mystery, intrigue, and — most importantly — the thrill of personal discovery. I’m far from suggesting that this entire “design born of fear” stems from malice or rank incompetence. Of course, market realities exist: the massive budgets of AAA projects require the widest possible audience, hence a low entry threshold. Retention metrics loom, where any player hesitation can be read as a potential churn point. Striving for “accessibility” all too often gets confused with dumbing-down the experience. All of that is understandable; I won’t argue with it. (A good, very brief framework article on this topic and key D1/D7/D30 metrics, etc: «Retention framework: Keep your players forever») Yet my game-designer’s skepticism whispers: have we chosen the most straightforward, but not the most elegant path? Isn’t this obsession with player “safety” a symptom of our own insecurity — our lack of faith in the worlds we create, the elegance of our systems, the fear that without hint-crutches the player simply won’t find the “fun”? Such an approach, in my view, doesn’t merely simplify the game — it risks devaluing the player’s agency, their capacity to think, analyze, and decide. It turns exploration from an exhilarating adventure into routine icon-clearing on a map. Reflecting on this design born of fear, I can’t shake a thought: are we overlooking the most obvious and powerful tool? That innate force that urges a child to dismantle a toy just to see how it works; that spark that drives a scientist to new discoveries, an explorer to uncharted lands. It is the fundamental engine of cognition — a basic need of the mind — to seek novelty, fill gaps in knowledge, solve riddles. Without that internal motor, without this unquenchable ▇▇▇▇, there would be no science, no art, no progress. It is ▇▇▇▇ that makes us ask “why?” and “how?”, that turns passive observation into active pursuit. So why don’t we, designers of interactive systems, place a bolder bet on that very ▇▇▇▇? Feel your brain trying to slot a word into those blanks? Even this simple guessing game — this tiny gap in the text — prompts you to tense up, analyze context, float hypotheses. Why? Because your brain can’t stand uncertainty. It was… curious. Exactly — curiosity. This small demonstration within a single paragraph shows how even a minimal mystery — a light stimulus to curiosity — instantly sparks our thought process, driving us to seek an answer. Isn’t a design that deliberately harnesses and rewards this innate pull toward discovery more elegant and, perhaps, more sustainable — a path to deep, meaningful engagement that arises from within rather than being imposed by external signposts? This article is no manifesto against the AAA industry, nor a paean to “hard-core” or indie game dev. Instead, it’s

I. Preface: «Guiding the blind (or pretending to be one?)»

Do you enjoy being mistrusted? Think back to that feeling when you tackle a new, intriguing task — whether it’s assembling a complex model, solving a puzzle, or finding your way along an unfamiliar route—and someone hovers over your shoulder. They prompt every step, point out the obvious, never give you a chance to trip, to ponder, to find the solution on your own. Annoying, isn’t it? It feels as though they take you for a fool who can’t put two and two together without outside help.

Perhaps I don’t understand something about life. Maybe today’s world really does demand maximum safety and the minimization of any effort or risk. But when I look at the game industry — especially its mainstream sector — I see a trend I’d call design born of fear: fear of losing the player, fear of seeming too difficult, fear of being rated poorly for “obscurity.” And that fear breeds a monster: hyper-protection. Games that should be spaces for exploration, experimentation, and triumph become interactive manuals where every step is predetermined, every puzzle comes with an obvious answer, and any hint of autonomy is immediately stifled by a pop-up hint or a bold map marker.

Here begins my personal designer’s irony — almost a tragedy. We, the creators of games, tirelessly declare at conferences, in interviews, and in books that games are a unique form of interactive art. We speak of deep dialogue with the player, of crafting a one-of-a-kind personal experience through interaction. Then we return to our design docs and, with our own hands, strangle that very artistic potential. Exploration, interpretation, self-reflection — the very essence of interactivity and art — are sacrificed to mechanical instruction-following. We turn the player from an explorer into a courier chasing GPS markers.

Imagine a director who, before a film screening, hands every viewer a detailed synopsis explaining every metaphor and even allows the audience to ignore theater etiquette and chatter loudly throughout… It’s as if we panic that the player “won’t get it,” so we drape the interactive canvas with layers of hints, killing mystery, intrigue, and — most importantly — the thrill of personal discovery.

I’m far from suggesting that this entire “design born of fear” stems from malice or rank incompetence. Of course, market realities exist: the massive budgets of AAA projects require the widest possible audience, hence a low entry threshold. Retention metrics loom, where any player hesitation can be read as a potential churn point. Striving for “accessibility” all too often gets confused with dumbing-down the experience. All of that is understandable; I won’t argue with it.

(A good, very brief framework article on this topic and key D1/D7/D30 metrics, etc: «Retention framework: Keep your players forever»)

Yet my game-designer’s skepticism whispers: have we chosen the most straightforward, but not the most elegant path? Isn’t this obsession with player “safety” a symptom of our own insecurity — our lack of faith in the worlds we create, the elegance of our systems, the fear that without hint-crutches the player simply won’t find the “fun”?

Such an approach, in my view, doesn’t merely simplify the game — it risks devaluing the player’s agency, their capacity to think, analyze, and decide. It turns exploration from an exhilarating adventure into routine icon-clearing on a map.

Reflecting on this design born of fear, I can’t shake a thought: are we overlooking the most obvious and powerful tool? That innate force that urges a child to dismantle a toy just to see how it works; that spark that drives a scientist to new discoveries, an explorer to uncharted lands. It is the fundamental engine of cognition — a basic need of the mind — to seek novelty, fill gaps in knowledge, solve riddles. Without that internal motor, without this unquenchable ▇▇▇▇, there would be no science, no art, no progress. It is ▇▇▇▇ that makes us ask “why?” and “how?”, that turns passive observation into active pursuit. So why don’t we, designers of interactive systems, place a bolder bet on that very ▇▇▇▇?

Feel your brain trying to slot a word into those blanks? Even this simple guessing game — this tiny gap in the text — prompts you to tense up, analyze context, float hypotheses. Why? Because your brain can’t stand uncertainty. It was… curious. Exactly — curiosity. This small demonstration within a single paragraph shows how even a minimal mystery — a light stimulus to curiosity — instantly sparks our thought process, driving us to seek an answer. Isn’t a design that deliberately harnesses and rewards this innate pull toward discovery more elegant and, perhaps, more sustainable — a path to deep, meaningful engagement that arises from within rather than being imposed by external signposts?

This article is no manifesto against the AAA industry, nor a paean to “hard-core” or indie game dev. Instead, it’s my analytical dissection of an alternative approach I’ll call “Designing Trust.” It’s a cool-headed attempt, using a game designer’s toolkit, to understand a philosophy that consciously rejects hyper-protection — a philosophy that stakes everything on the player’s intelligence, observation, and tenacity; that turns ignorance, uncertainty, and the need for exploration not into barriers but into core mechanics.

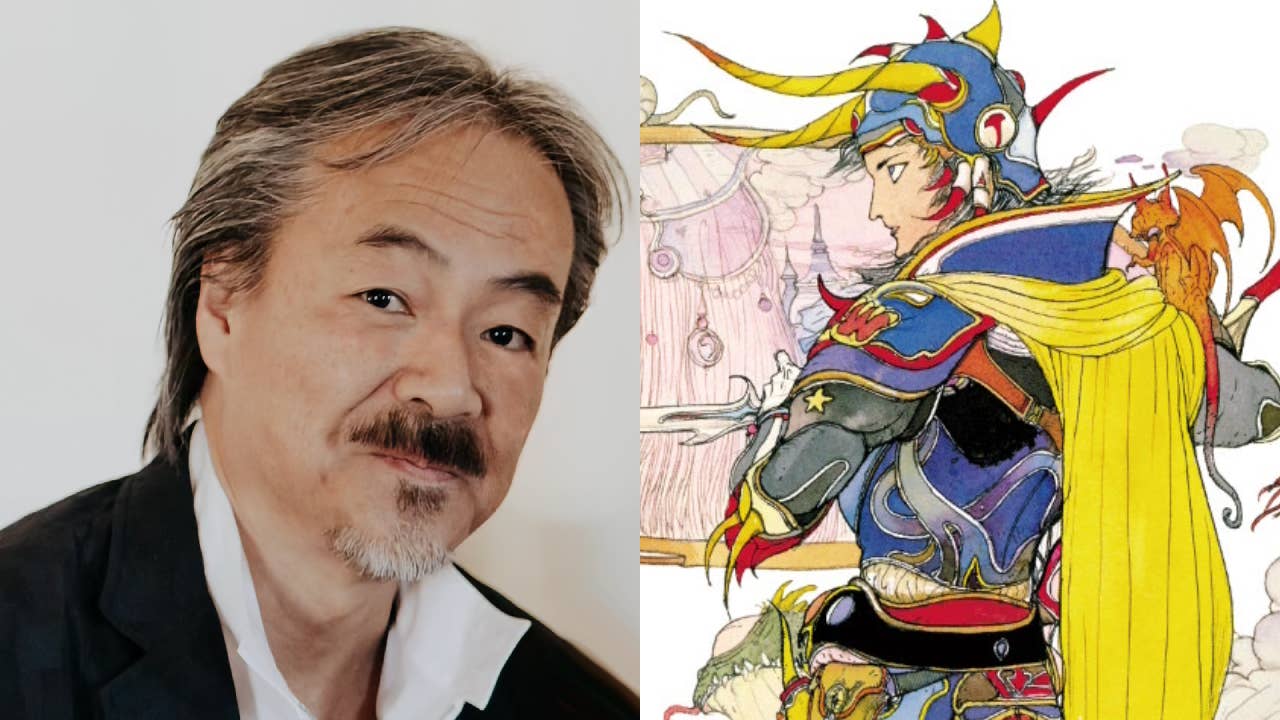

To keep this discussion from remaining purely theoretical, we’ll dissect three notable specimens of this Design of Trust. We’ll peek under the hood of:

- Animal Well — a labyrinthine game where self-learning is woven into the world’s fabric.

- The Witness — a language-game proving that even the most complex rules can be taught without a single word.

- Outer Wilds — a mechanism-game where knowledge is the only key and curiosity the fuel.

My aim isn’t to turn the industry upside-down, but to offer another lens for analysis and design — to show that trusting the player isn’t just a pretty slogan, but a working design tool capable of producing unique and truly memorable game experiences. Let’s see how it works.

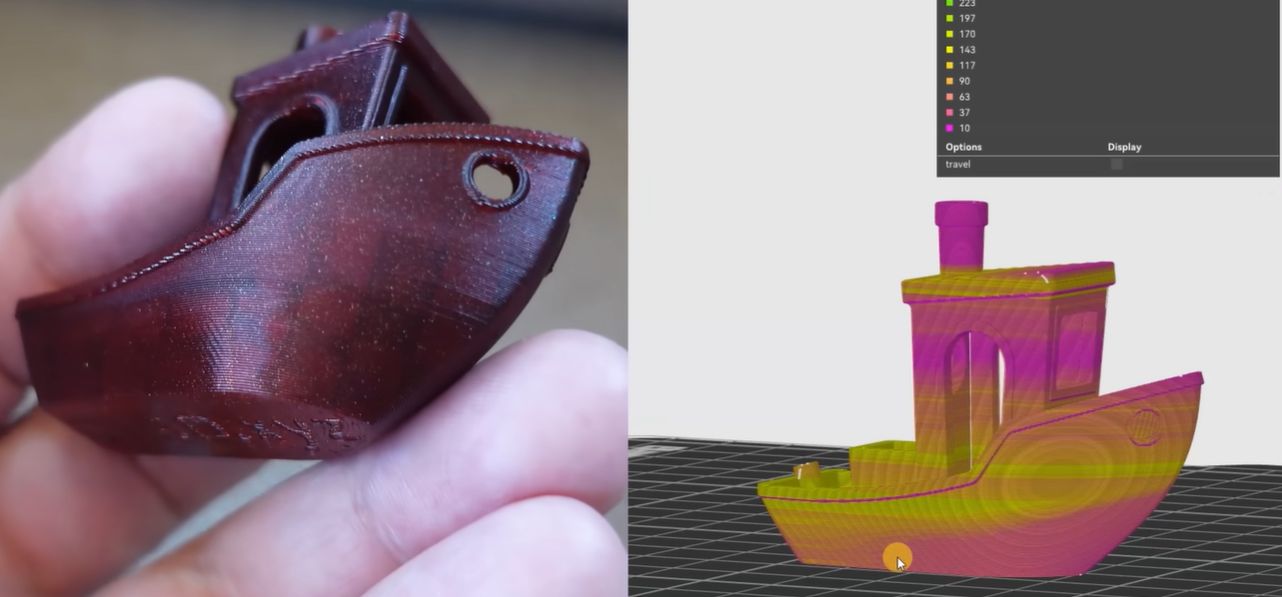

II. Part 1: Animal Well — “I See No Evil”

![[The AI Show Episode 156]: AI Answers - Data Privacy, AI Roadmaps, Regulated Industries, Selling AI to the C-Suite & Change Management](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20156%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

_incamerastock_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Nothing Phone (3) has a 50MP ‘periscope’ telephoto lens – here are the first samples [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/nothing-phone-3-telephoto.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)