This battery recycling company is now cleaning up AI data centers

In a sandy industrial lot outside Reno, Nevada, rows of battery packs that once propelled electric vehicles are now powering a small AI data center. Redwood Materials, one of the US’s largest battery recycling companies, showed off this array of energy storage modules, sitting on cinder blocks and wrapped in waterproof plastic, during a press…

In a sandy industrial lot outside Reno, Nevada, rows of battery packs that once propelled electric vehicles are now powering a small AI data center.

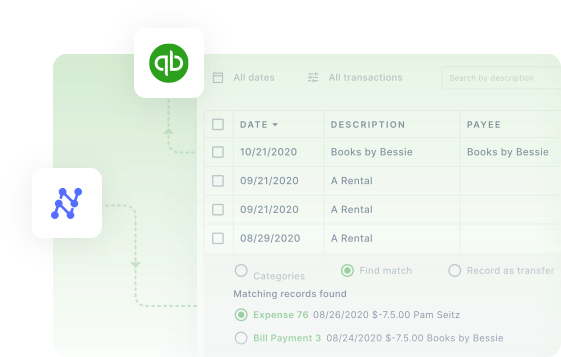

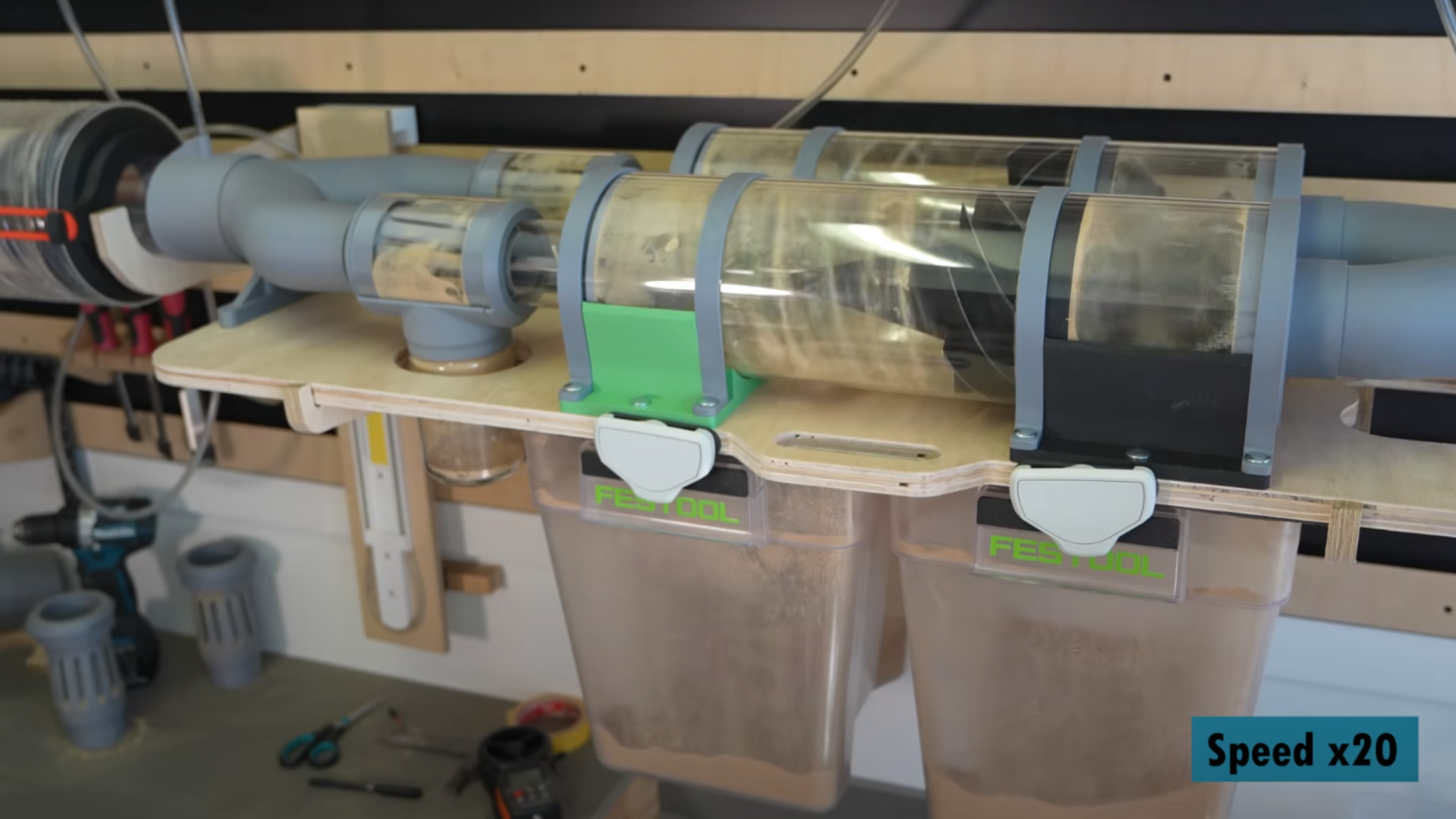

Redwood Materials, one of the US’s largest battery recycling companies, showed off this array of energy storage modules, sitting on cinder blocks and wrapped in waterproof plastic, during a press tour at its headquarters on June 26.

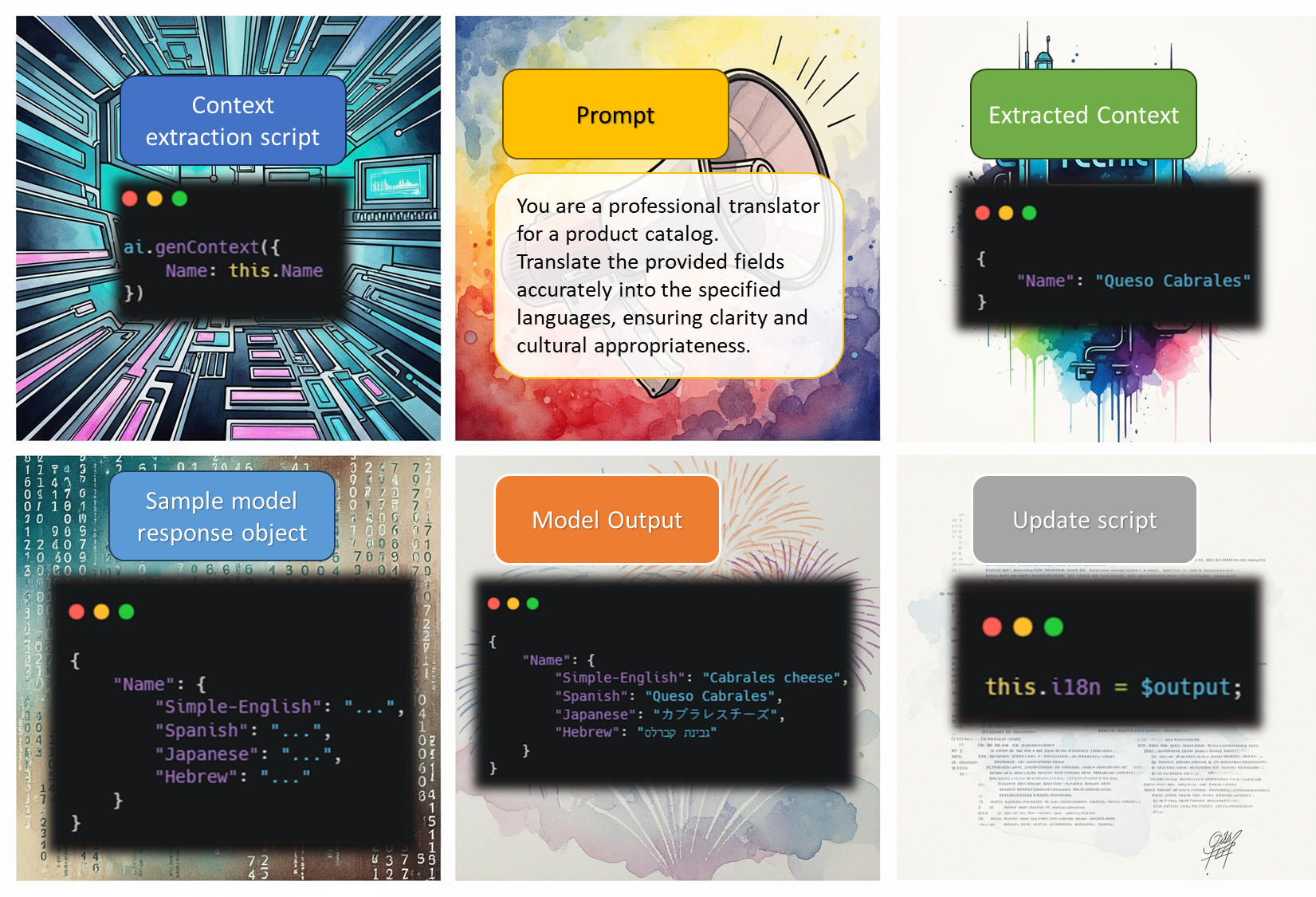

The event marked the launch of the company’s new business line, Redwood Energy, which will initially repurpose (rather than recycle) batteries with years of remaining life to create renewable-powered microgrids. Such small-scale energy systems can operate on or off the larger electricity grid, providing electricity for businesses or communities.

Redwood Materials says many of the batteries it takes in for processing retain more than half their capacity.

“We can extract a lot more value from that material by using it as an energy storage project before recycling it,” JB Straubel, Redwood’s founder and chief executive, said at the event.

This first microgrid, housed at the company’s facility in the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center, is powered by solar panels and capable of generating 64 megawatt-hours of electricity, making it one of the nation’s largest such systems. That power flows to Crusoe, a cryptocurrency miner that pivoted into developing AI data centers, which has built a facility with 2,000 graphics processing units adjacent to the lot of repurposed EV batteries.

(That’s tiny as modern data centers go: Crusoe is developing a $500 billion AI data center for OpenAI and others in Abilene, Texas, where it expects to install 100,000 GPUs across its first two facilities by the end of the year, according to Forbes.)

Redwood’s project underscores a growing interest in powering data centers partially or entirely outside the electric grid. Not only would such microgrids be quicker to build than conventional power plants, but consumer ratepayers wouldn’t be on the hook for the cost of new grid-connected power plants developed to serve AI data centers.

Since Redwood’s batteries are used, and have already been removed from vehicles, the company says its microgrids should also be substantially cheaper than ones assembled from new batteries.

Redwood Energy’s microgrids could generate electricity for any kind of operation. But the company stresses they’re an ideal fit for addressing the growing energy needs and climate emissions of data centers. The energy consumption of such facilities could double by 2030, mainly due to the ravenous appetite of AI, according to an April report by the International Energy Agency.

“Storage is this perfectly positioned technology, especially low-cost storage, to attack each of those problems,” Straubel says.

The Tahoe Reno Industrial Center is the epicenter of a data center development boom in northern Nevada that has sparked growing concerns about climate emissions and excessive demand for energy and water, as MIT Technology Review recently reported.

Straubel says the litany of data centers emerging around it “would be logical targets” for its new business line, but adds there are growth opportunities across the expanding data center clusters in Texas, Virginia and the Midwest as well.

“We’re talking to a broad cross section of those companies,” he says.

Crusoe, which also provides cloud services, recently announced a joint venture with the investment firm Engine No. 1 to provide “powered data center real estate solutions” to AI companies by constructing 4.5 gigawatts of new natural-gas plants.

Redwood’s microgrid should provide more than 99% of the electricity Crusoe’s local facilities need. In the event of extended periods with little sunlight, a rarity in the Nevada desert, the company could still draw from the standard power grid.

Cully Cavness, cofounder and operating chief of Crusoe, says the company is already processing AI queries and producing conclusions for its customers at the Nevada facility. (Its larger data centers are dedicated to the more computationally intensive process of training AI models.)

Redwood’s new business division offers a test case for a strategy laid out in a paper late last year, which highlighted the potential for solar-powered microgrids to supply the energy that AI data centers need.

The authors of that paper found that microgrids could be built much faster than natural-gas plants and would generally be only a little more expensive as an energy source for data centers, so long as the facilities could occasionally rely on natural-gas generators to get them through extended periods of low sunlight.

If solar-powered microgrids were used to power 30 gigawatts of new AI data centers, with just 10% backup from natural gas, it would eliminate 400 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions relative to running the centers entirely on natural gas, the study found.

“Having a data center running off solar and storage is more or less what we were advocating for in our paper,” says Zeke Hausfather, climate lead at the payments company Stripe and a coauthor of the paper. He hopes that Redwood’s new microgrid will establish that “these sorts of systems work in the real world” and encourage other data center developers to look for similar solutions.

Redwood Materials says electric vehicles are its fastest-growing source of used batteries, and it estimates that more than 100,000 EVs will come off US roads this year.

The company says it tests each battery to determine whether it can be reused. Those that qualify will be integrated into its modular storage systems, which can then store up energy from wind and solar installations or connect to the grid. As those batteries reach the end of their life, they’ll be swapped out of the microgrids and moved into the company’s recycling process.

Redwood says it already has enough reusable batteries to build a gigawatt-hour’s worth of microgrids, capable of powering a little more than a million homes for an hour. In addition, the company’s new division has begun designing microgrids that are 10 times larger than the one it unveiled this week.

Straubel expects Redwood Energy to become a major business line, conceivably surpassing the company’s core recycling operation someday.

“We’re confident this is the lowest-cost solution out there,” he says.

![[The AI Show Episode 156]: AI Answers - Data Privacy, AI Roadmaps, Regulated Industries, Selling AI to the C-Suite & Change Management](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20156%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

_incamerastock_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Senators reintroduce App Store bill to rein in ‘gatekeeper power in the app economy’ [U]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/06/app-store-senate.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)