Look inside Zeno Power’s ‘kitchen,’ where engineers test recipes for nuclear batteries

Researchers are fine-tuning a recipe at Zeno Power’s office-lab complex in Seattle’s South Lake Union district — but it’s not the kind of recipe you can taste-test. Instead, this recipe specifies the ingredients for a new kind of nuclear battery, and Zeno is hoping it’ll get a glowing review. “Our vision for Zeno is to be building dozens, and eventually hundreds of these power systems every year,” Zeno CEO and co-founder Tyler Bernstein told me during a recent tour of the 15,000-square-foot facility. “So, we want to make sure that from the early days, as we’re developing the process for… Read More

Researchers are fine-tuning a recipe at Zeno Power’s office-lab complex in Seattle’s South Lake Union district — but it’s not the kind of recipe you can taste-test. Instead, this recipe specifies the ingredients for a new kind of nuclear battery, and Zeno is hoping it’ll get a glowing review.

“Our vision for Zeno is to be building dozens, and eventually hundreds of these power systems every year,” Zeno CEO and co-founder Tyler Bernstein told me during a recent tour of the 15,000-square-foot facility. “So, we want to make sure that from the early days, as we’re developing the process for how we build these heat sources, we’re doing it in a way that we can scale very quickly to meet the demand that we’re seeing from government and commercial customers.”

Zeno Power plans to demonstrate its first full-scale radioisotope power system in 2026, and deliver its first commercially built nuclear batteries by 2027. The potential applications range from powering infrastructure on the bottom of the ocean, to keeping machines operational in the Arctic, to charging up rovers on the moon.

The idea behind the nuclear battery goes back decades: Radioisotope thermoelectric generators — which convert the heat given off by radioactive materials into electricity — have powered devices ranging from Apollo-era experiments on the moon, to rovers on Mars, to the interplanetary probe that zoomed past Pluto.

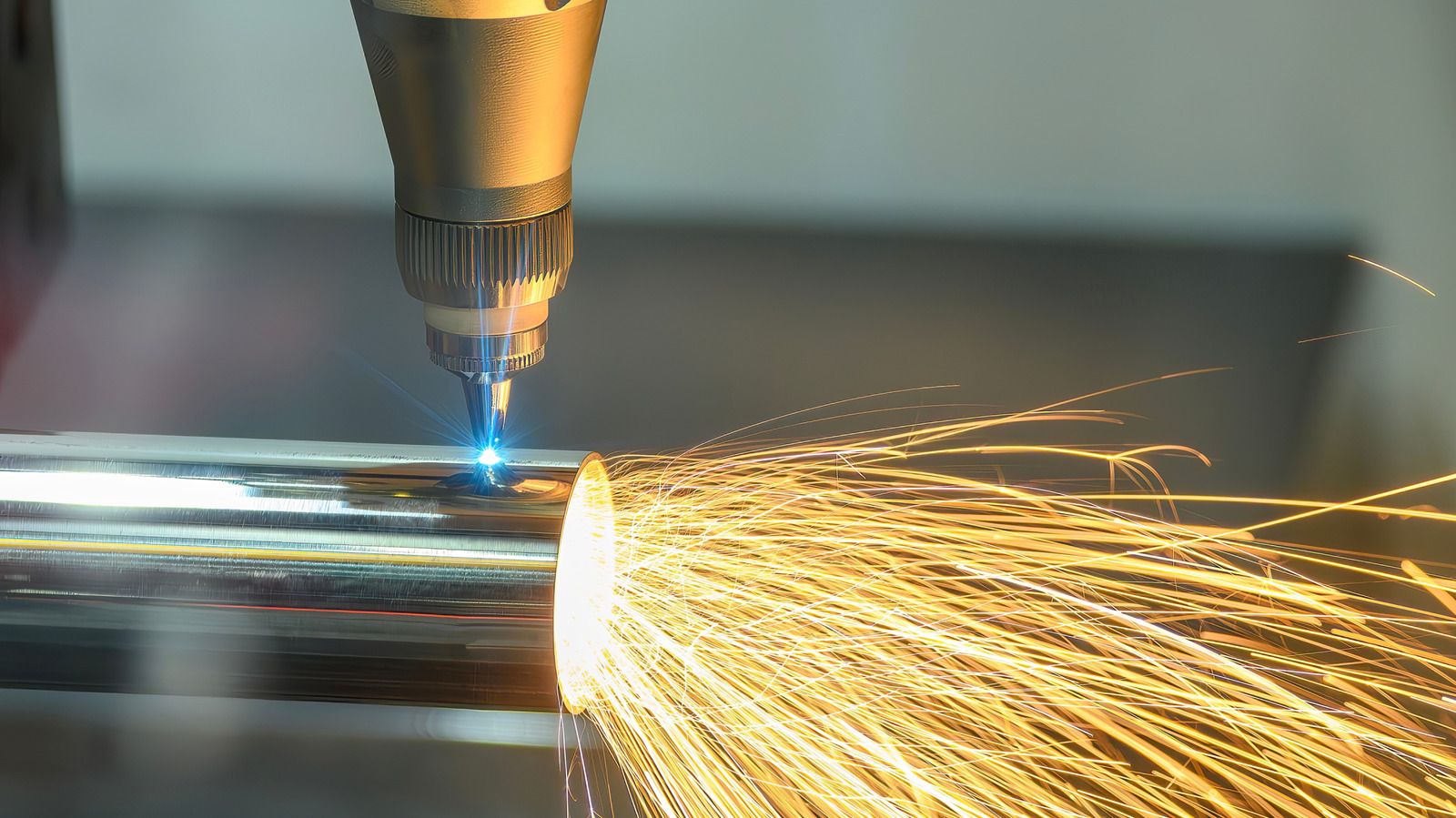

Those devices were powered by plutonium-238, which is relatively expensive and in short supply. Zeno is working on a new type of nuclear battery that uses a different radioactive isotope, strontium-90. That isotope is typically produced in nuclear fission reactors. It’s more plentiful and less costly than plutonium; however, strontium-powered batteries are typically bulkier than plutonium-powered batteries, constraining their use.

Zeno is betting that its technology — in effect, its recipe for manufacturing a strontium-based heat source — will change the cost equation in its favor, opening up new applications for nuclear batteries. And you can think of Zeno’s Seattle lab as the company’s test kitchen.

Zeno got its start in 2018 as a spin-off at Vanderbilt University, and currently has offices in Seattle as well as Washington, D.C. Many of its more than 65 employees work in Seattle. “Today we have about 45 people here,” said Bernstein, who was visiting from D.C. when we spoke. “And in the next few years we’ll grow to about 75 people here.”

Zeno’s researchers and their collaborators at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory chalked up an early success in 2023 when they demonstrated a heat source that made use of strontium-90. Now the Seattle team is testing different combinations of ingredients to make Zeno’s power system as efficient as possible.

The Seattle operation currently uses a non-radioactive isotope, strontium-88, and manually prepares hundreds of different recipes that would work with strontium-90. The most promising recipe will be used at a Westinghouse Electric facility in Pennsylvania to fabricate Zeno’s production-grade heat sources.

During my visit to the Seattle lab, Zeno’s chemists showed off the test pellets that they use in their experiments. The pellets that come out of the lab’s presses typically look like half-inch-wide watch batteries, but Zeno also makes scaled-up disks of experimental material that are closer to the size of Olympic-style medals. These larger pellets resemble those that will eventually be used in Zeno’s full-scale nuclear heat sources.

In another lab space, a 3D printer can produce prototypes for other components of Zeno’s batteries, including a case for the heat source that looks like a small thermos bottle. (And in fact, Zeno’s employees were given thermos bottles that look like its heat-sources. Each gift bottle was personalized with the employee’s initials and employee number.)

On a different floor of Zeno’s facility, a separate lab is being readied for experiments that will use low-level radioactive materials. That lab has a set of argon-filled gloveboxes that researchers will be able to use to handle those test materials safely.

Bernstein told me that Zeno is planning three product lines. “That’s our radioisotope heater unit, a radioisotope thermoelectric generator and a radioisotope Stirling generator,” he said.

The heater unit is the simplest product, designed for environments where heat is a higher priority than electricity. “A great example of that is surviving the lunar night,” Bernstein said.

For solar-powered spacecraft on the moon, 14 days of total darkness and extreme cold can be a real killer, as demonstrated by the demise of Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lunar lander in March. “Instead, if you put heaters on these landers or rovers in the future, that could allow them to enter hibernation during the two weeks of darkness,” Bernstein said. “They may not have electricity to operate, but they have the heat to stay alive so they can wake up on the next lunar day.”

The next step up would be Zeno’s radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs, which can convert roughly 5% of the energy from the heat source into electricity. Those devices would fit into the traditional niche for space power units. A venture called ispace recently announced that it’s aiming to send one of Zeno’s power units to the moon in 2027. (Ispace’s most recent attempt to put a lander on the moon failed earlier this month.)

Zeno’s Stirling generator would mark a significant increase over RTGs in energy conversion efficiency. “This is right now at a lower technology readiness level, but we have two programs, working with NASA and with the Department of Defense, where we’re maturing the Stirling engine,” Bernstein said.

The $7.5 million Pentagon program, known as DEPTHS, seeks to demonstrate how a radioisotope Stirling generator could be used as a power source in a maritime environment. A tank-based demonstration is scheduled for 2026.

“There are a lot of government applications where it could be powering seabed infrastructure,” Bernstein said. “Also a lot of exciting commercial opportunities for protecting critical infrastructure on the seabed, such as telecom cables — or potentially supporting the nascent deep-sea mining industry.”

Zeno’s partners in DEPTHS include Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space venture and another Seattle-area company called PowerLight Technologies, which is working on power transmission systems that use optical fiber.

Blue Origin is also partnering with Zeno on a $15 million NASA Tipping Point program known as Project Harmonia. Project Harmonia focuses on using americium-241 rather than strontium-90 for the heat source. “There is more development needed on the technology, and also on the supply chain for this material,” Bernstein said. “So really, it’s the latter part of the decade that we’ll look at for the first demonstrations for that.”

A recent $50 million funding round served as a vote of confidence from investors who are in it for the long haul. “We invest in companies with the potential to define entire industries — and we believe Zeno Power is one of them,” Lior Prosor, partner at Hanaco Ventures, said in a news release.

Bernstein says the general public may not know much about the nuclear technology Zeno is working on today, but he thinks it won’t take long for people to catch on.

“The core vision of Zeno is to take material that is a waste product, that is a liability to the U.S. taxpayer and the Department of Energy, and recycle it to build these power systems — to support national security, support space exploration, to support energy resiliency,” he said. “We’ve found that’s a message and a vision that a lot of people can get behind.”

Bernstein, meanwhile, has gotten behind the Pacific Northwest as the home base for the company’s engineering team — in part because it’s also home to space companies such as Blue Origin, research centers such as Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, and other nuclear ventures such as TerraPower and Helion Energy.

“Seattle is a really great place where there’s this nexus of aerospace and nuclear. People seem to love this place and don’t want to leave it,” he said.

He admitted that it can be challenging to manage a bicoastal operation that’s split between Seattle and the other Washington. “But at the same time, there are advantages,” he said. “The talent pool in Seattle is terrific. In D.C., the proximity to a lot of our customers and our regulators and the policymakers is terrific. So, I’d say the challenges are real, but there’s also a significant upside. There’s a great division of labor between the two places.”

![[The AI Show Episode 152]: ChatGPT Connectors, AI-Human Relationships, New AI Job Data, OpenAI Court-Ordered to Keep ChatGPT Logs & WPP’s Large Marketing Model](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20152%20cover.png)

![Designing a Robust Modular Hardware-Oriented Application in C++ [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/f2sQd76t.webp)

_Alexander-Yakimov_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Zoonar_GmbH_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![AirPods Pro 3 Not Launching Until 2026 [Pu]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97620/97620/97620-640.jpg)

![Apple Releases First Beta of iOS 18.6 and iPadOS 18.6 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97626/97626/97626-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds watchOS 11.6 Beta to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97627/97627/97627-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds tvOS 18.6 Beta to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97628/97628/97628-640.jpg)

![T-Mobile customers' address, number, and other info allegedly up for sale; company denies claim [UPDATED]](https://m-cdn.phonearena.com/images/article/171306-two/T-Mobile-customers-address-number-and-other-info-allegedly-up-for-sale-company-denies-claim-UPDATED.jpg?#)