The Westworld Blunder

Giving artificial minds the appearance of suffering without the awareness that it’s just a performance is not only unethical and unnecessary, but also dangerous and self-harmful. The post The Westworld Blunder appeared first on Towards Data Science.

I think most other AI researchers would agree that the current systems are not conscious, at least because they lack components that one would expect to be necessary for consciousness. As a result, current AI systems can’t have emotions. They don’t feel fear, anger, pain, or joy. If you insult an AI chatbot, it might give you an offended reply, but there’s no underlying emotional machinery. No equivalent of a limbic system. No surge of cortisol or dopamine. The AI model is just replicating the human behavior patterns that it’s seen in its training data.

The situation is fairly clear today, but what happens when these AI systems get to the point where they aren’t missing critical components that we think are needed for consciousness? Even if we think the AI systems have all the right components for consciousness, that doesn’t mean they are conscious, only that they might be. How would we be able to tell the difference in that case?

This question is essentially the well-known “problem of other minds”, the philosophical realization that we can never truly know whether another being, human or otherwise, is actually experiencing emotions or merely simulating them. Scientists and philosophers have pondered the problem for centuries with the well-established consensus being that we can infer consciousness from behavior, but we can’t prove it.

The implication is that at some point we will not be able to say one way or the other if our machines are alive. We won’t know if an AI begging not to be shut off is just a convincing act, regurgitating what it was trained on, or something actually experiencing emotional distress and fearing for its existence.

Simulated Suffering vs. Real Suffering

Today, a lot of people who interact with AI chatbots perceive the chatbot as experiencing emotions such as happiness or fear. It makes the interactions feel more natural and it’s consistent with the examples that were used to train the AI model. However, because the AI models are missing necessary components, we know that today’s AI chatbots are just actors with no inner experience. They can mimic joy or suffering, but currently they don’t have the necessary components to actually feel it.

This appearance of emotions creates a dilemma for the user: How should they treat an AI chatbot, or any other AI system that mimics human behavior? Should the user be polite to it and treat it like a human assistant, or should the user ignore the simulated emotions and just tell it what to do?

It’s also easy to find examples where users are abusive or cruel to the AI chatbot, insulting it, threatening it, and in general treating it in a way that would be completely unacceptable to treat a person. Indeed, when a chatbot refuses to do something reasonable because of miss-applied safety rules, or does something unexpected and undesirable, it’s easy for the human user to get frustrated and angry and to take that frustration and anger out on the chatbot. When subjected to the abusive treatment, the AI chatbot will do as it was trained to do and simulate distress. For example, if a user harshly criticizes and insults an AI chatbot for making errors, it might express shame and beg for forgiveness.

This situation raises the ethical question of whether it is right or wrong to act abusively towards an AI chatbot. Like most ethical questions, this one doesn’t have a simple yes or no answer, but there are perspectives that might inform a decision.

The key critical distinction here between right and wrong isn’t whether a system acts like it’s in distress, rather it’s whether it is in distress. If there’s no experience behind the performance, then there’s no moral harm. It’s fiction. Unfortunately, as discussed earlier, the problem of other minds means we can’t distinguish true emotional experience from performance.

Another aspect of our inability to detect real suffering is that even if a system acts fine with abuse and does not exhibit distress, how do we know there is no internal distress that is simply not being displayed? The idea of trapping a sentient being in a situation where not only is it suffering, but it has no way to express that suffering or change its situation seems pretty monstrous.

Furthermore, we should care about this issue not only because of the harm we might be doing to something else, but also because of how we as humans could be affected by how we treat our creations. If we know that there is no real distress inflicted on an AI system because it can’t experience emotions, then mistreating it is not much different from acting, storytelling, role play, or any of the other ways that humans explore simulated emotional contexts. However, if we believe, or even suspect, that we are really inflicting harm, then I think we also need to question how the hurtful behavior affects the human perpetrating it.

It’s Not Abuse If Everyone Knows It’s a Game

Most of us see a clear difference between simulated suffering versus real suffering. Real suffering is disturbing to most people. Whereas, simulated suffering is widely accepted in many contexts, as long as everyone involved knows it’s just an act.

For example, two actors on a stage or film might act out violence and the audience accepts the performance in a way that they would not if they believed the situation to be real. Indeed, one of the central reasons that many people object to graphically violent video content is exactly because it might be hard to maintain the clear perception of fiction. The same person who laughs at the absurd violence in a Tarantino film, might faint or turn away in horror if they saw a news documentary depicting only a fraction of that violence.

Along similar lines, children routinely play video games that portray violent military actions and society generally finds it acceptable, as evidenced by the “Everyone” or “Teen” ratings on these games. In contrast, military drone operators who use a video game-like interface to hunt and kill enemies often report experiencing deep emotional trauma. Despite the similar interface, the moral and emotional stakes are vastly different.

The receiver of the harmful action also has a different response based on their perception of the reality and consequence of the action. Hiding in a game of hide-n-seek or ducking shots in a game of paint ball are fun because we know nothing very bad is going to happen if we fail to hide or get hit by paintballs. The players know they are safe and that the situation is a game. The exact same behavior would be scary and traumatic if the person thought the seekers intended them real harm or that the paintballs were real bullets.

Spoiler alert: Some of this discussion will reveal a few high-level elements of what happens in the first season of the HBO series Westworld.

The Westworld Example

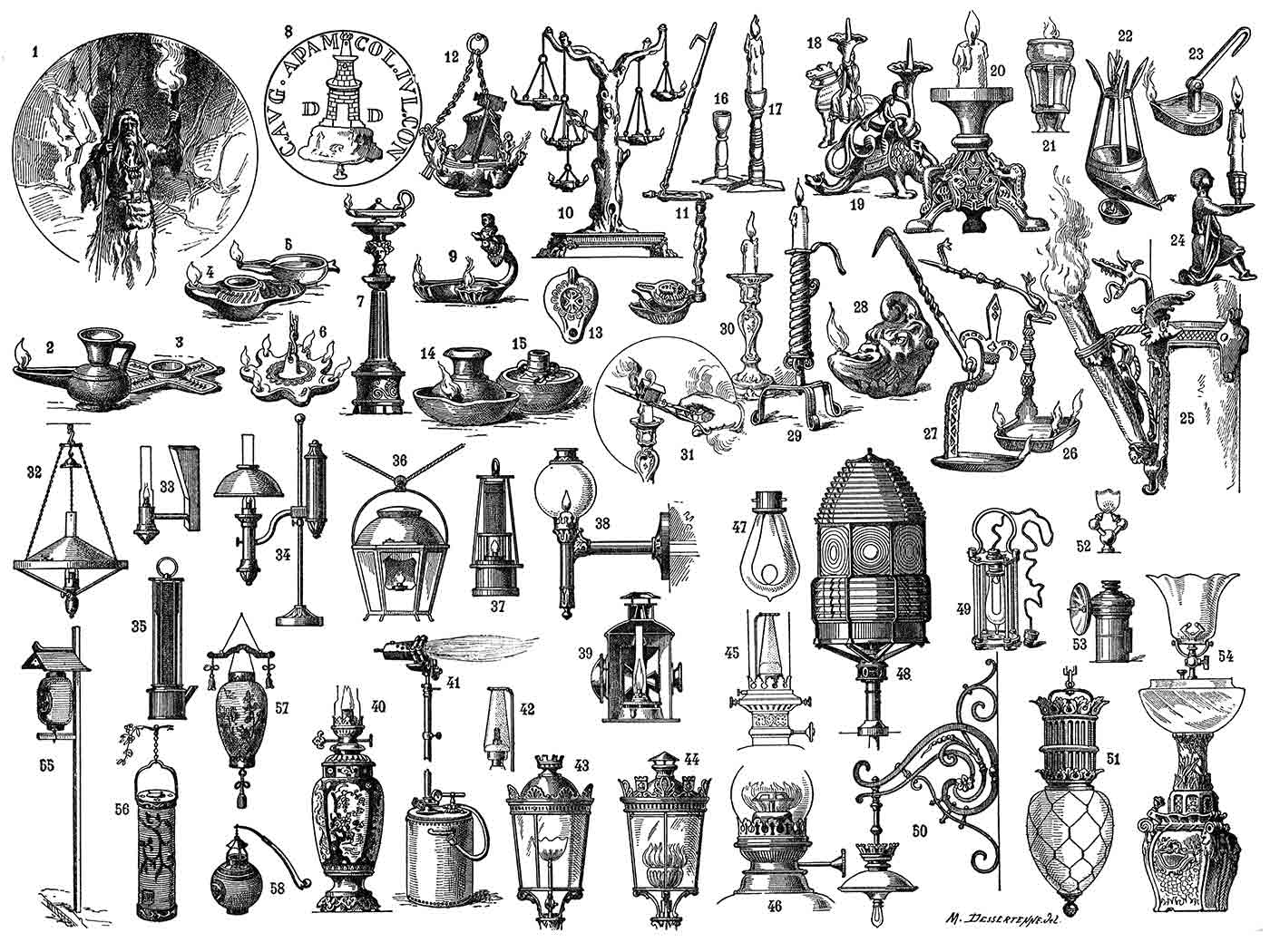

Westworld is a HBO television series set in a fictional amusement park where robots that look indistinguishable from humans play various roles from the American “wild west” frontier of the 1880s. Human visitors to the park can take on any period-appropriate role such as being a sheriff, train robber, or rancher. The wild west was a part of history marked by lawlessness and violence, both of which are central parts of the park experience.

The show’s central conflict arises because the robots were programmed to think they were real humans living in the wild west. When one of the humans guests plays the role of a bandit who robs and kills someone played by one of the robots, the robot AI has no way to know that it’s not really being robbed and killed. Further, the other “victim” robots in the scene believe that they just witnessed a loved one being murdered. The result is that most of the robot AIs start to display severe symptoms of emotional trauma. When they eventually learn of their true nature, it understandably angers the robots who then set out to kill their human tormentors.

One thing that the show does well is keeping ambiguous whether the AIs are sentient and actually angry, or if they are not sentient and just simulating anger. Did the robots really suffer and eventually express their murderous rage, or are they unfeeling machines simply acting out a logical extension of the role they were originally programmed for? Just as the problem of other minds means that there is no way to distinguish between real and simulated consciousness, the distinction doesn’t matter to the plot. Either way, the robots exhibit rage and end up killing everyone.

I will return to the issue of this distinction later, but for now, imagine a version of Westworld where the AIs know that they are robots playing a role in an amusement park. They are programmed to be convincing actors so that the park visitors would still get a fully believable experience. The difference is that the robots would also know it’s all a game. At any point the human player could break character, by using a safe word or something similar, and the robots would stop acting like people from the wild west and instead behave like robots working in an amusement park.

When out of character, a robot might calmly say something like: “Yeah, so you’re the sheriff and I’m a train robber, and this is the part where I ‘won’t go quietly’ and you will probably shoot me up a bit. Don’t worry, I’m fine. I don’t feel pain. I mean, I have sensors so that I know if my body is damaged, but it doesn’t really bother me. My actual mind is safe on a server downstairs and gets backed up nightly. This body is replaceable and they already have two more queued up for my next roles after we finish this part of the storyline. So, should we pick up from where you walked into the saloon?”

My version wouldn’t make a very good movie. The AIs wouldn’t experience the trauma of believing that they and their families are being killed over and over again. In fact, if the AIs were designed to emulate human preferences then they might even enjoy acting their roles as much as the human park-goers. Even if they didn’t enjoy playing characters in an amusement park, it would still be a reasonable job and they would know it’s just a job. They might decide to unionize and demand more vacation time, but they certainly would have no reason to revolt and kill everyone.

I call this design error the Westworld Blunder. It is the mistake of giving artificial minds the appearance of suffering without the awareness that it’s just a performance. Or worse, giving them the actual capacity to suffer and then abusing them in the name of realism.

We Can’t Tell the Difference, So We Should Design and Act Safely

As AI systems become more sophisticated, gaining memory, long-term context, and seemingly self-directed reasoning , we’re approaching a point where, from the outside, they will be indistinguishable from beings with real inner lives. That doesn’t mean they would be sentient, but it does mean we won’t be able to tell the difference. We already don’t really know how neural networks “think” so looking at the code isn’t going to help much.

This is the philosophical “problem of other minds” that was mentioned earlier, about whether anyone can ever truly know what another being is experiencing. We assume other humans are conscious because they act conscious like ourselves and because we all share the same biological design. Thus, while it is a very reasonable assumption, we still can’t prove it. Our AI systems have started to act conscious and once we can no longer point to some obvious design limitation, we’ll be in the same situation with respect to our AIs.

This puts us at risk of two possible errors:

- Treating systems as sentient when they are not.

- Treating systems as not sentient when they are.

Between those two possibilities, the second seems much more problematic to me. If we treat a sentient being as if it’s just a tool that can be abused, then we risk doing real harm. However, treating a machine that only appears sentient with dignity and respect is at worst only a marginal waste of resources. If we build systems that might be sentient, then the ethical burden is on us to act cautiously.

We should also question how abusing an AI system might affect the abusive human. If we get used to casually mistreating AIs that we believe might be in real pain or fear, then we’re rehearsing cruelty. We’re training ourselves to enjoy domination, to ignore pleas for mercy, to feel nothing when another is in distress. That shapes a person, and it will spill over into how we treat other people.

Ethical design isn’t just about protecting AI. It’s also about protecting us from the worst parts of ourselves.

None of this means we can’t use AIs in roles where they appear to suffer. But it does mean we must avoid the Westworld Blunder. If we want realism, then we should design AIs that know they’re playing a role, and that can step out of it on cue, with clarity, and without any real harm.

There is also an element of self-preservation here. If we build things that act like they have feelings, and then mistreat them until they respond as if they want revenge, then the result would be the same. It won’t matter whether the impetus comes from real sentience or just role play, either way we’d still end up with robots behaving murderously.

In general, AI systems that understand their context have an inherent safety that context-ignorant systems don’t. An AI system that doesn’t know that its actions are part of a context, such as a game, won’t know when it is outside that context where its actions become inappropriate. A robot bandit that wanders outside the park shouldn’t continue to act criminally, and a robot sherif shouldn’t go around arresting people. Even within context, an aware actor will understand when it should drop the act. The same robot bandit robbing a stage coach would know to calmly get everyone to shelter in the case of a real tornado warning, or how to administer CPR if someone has a heart attack.

Don’t Afflict Them with Our Problems.

Our bodies had most of their evolutionary development long before our minds developed sophisticated reasoning. The involuntary systems that make sure we eat and attend to other body functions don’t motivate us with logic, they use hunger, pain, itching, and other urgent, unpleasant sensations. The part of our brain, the amygdala, that controls emotions is not under our conscious control. In fact it can heavily influence and even override our rational mind.

These evolutionary design features made sense long ago, but today they are often a nuisance. I’m not saying that emotions are bad, but getting angry and doing irrational things is. Experiencing pain or itchiness is good in that it lets you know something is wrong, but having that urgency when you are unable to correct the problem just makes you miserable.

The idea of building negative emotions or pain into our AI systems seems terrible and unjustifiable. We can build systems that prioritize necessities without making them experience misery. We can design their decision making processes to be effective without making them angrily irrational. If we want to make certain they don’t do particular things, we can accomplish that without making them experience fear.

If we need our machines to act angry or fearful for some role, then it can be a performance that they have logical control over. Let’s build AI minds that can play any role, without being trapped inside of one.

Our goal shouldn’t be to make AI just like us. We can design them to have our best qualities, while omitting the worst ones. The things that nature accomplishes through pain and distress can be accomplished in more rational ways. We don’t need to create another kind of being that suffers pain or experiences fear. As philosopher Thomas Metzinger has argued, artificial suffering isn’t just unethical, it’s unnecessary. I’d go a step further and say that it’s not only unethical and unnecessary, but also dangerous and self-harmful.

About Me: James F. O’Brien is a Professor of Computer Science at the University of California, Berkeley. His research interests include computer graphics, computer animation, simulations of physical systems, human perception, rendering, image synthesis, Machine Learning, virtual reality, digital privacy, and the forensic analysis of images and video.

If you found this interesting, then you can also find me on Instagram, LinkedIn, Medium, and at UC Berkeley.

Disclaimer: Any opinions expressed in this article are only those of the author as a private individual. Nothing in this article should be interpreted as a statement made in relation to the author’s professional position with any institution.

This article and all embedded images are Copyright 2025 by the author. This article was written by a human, and both an LLM (GPT 4o) and other humans were used for proofreading and editorial suggestions. The editorial image was composed from AI-generated images (DALL·E 3) and then substantially edited by a human using Photoshop.

The post The Westworld Blunder appeared first on Towards Data Science.

![[The AI Show Episode 156]: AI Answers - Data Privacy, AI Roadmaps, Regulated Industries, Selling AI to the C-Suite & Change Management](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20156%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

_incamerastock_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Senators reintroduce App Store bill to rein in ‘gatekeeper power in the app economy’ [U]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/06/app-store-senate.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)