Venmo’s dubious defaults look like a permanent privacy foul

If it weren’t for Signal, Venmo might be the most infamous app of the Trump administration—and maybe the most beloved among journalists covering this White House. That’s not because of any Trump staffer’s clumsiness, like the one that led national security advisor Mike Waltz to accidentally add Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg to a Signal chat group set up to discuss military strikes against Houthi terrorists. With the PayPal-owned payments app, the blame (or credit) goes to its default setting of making users’ friends lists public. Vice President JD Vance ran afoul of that in July, when Wired identified the Venmo account of then-Sen. Vance (R-Ohio) and found 211 names on his friends list: a mix of tech executives, politicians, and journalists. Wired repeated the exercise in March for Waltz and found 328 Venmo friends covering a similar range of Washington society. And on Tuesday, NOTUS reported that among “more than 50 current lawmakers, more than 20 former members of Congress, and more than three dozen current Trump administration officials and nominees” whose Venmo accounts the site identified over a week of research, “almost everyone had their friends lists open to the public.” “It just keeps happening,” says Sara Collins, director of government affairs at the Washington-based digital-rights group Public Knowledge. Who does this serve? Venmo has historically defended this default as part of its social nature, much like it once made transactions public by default, despite vocal criticism. That payment publicity persisted even after Venmo settled a Federal Trade Commission investigation into that and other alleged deceptive conduct. Venmo didn’t remove the public transactions feed until 2021. PayPal spokesperson Erin Mackey responded to Fast Company with a statement similar to what the company has offered in previous stories about Venmo privacy. “The privacy and safety of Venmo users are top priorities,” she wrote. “Venmo provides in-app education and easy-to-use privacy settings to put users in control of who their friends lists are shared with or whether they appear in other users’ lists at all.” Her statement ended with a line that departs slightly from prior responses: “We’re always listening to our customers to strengthen and evolve the Venmo platform while staying true to the social aspects they’ve come to know and love.” Privacy advocates find Venmo’s public friends-list default nearly as troubling as the old public transactions feed. “It’s not a good practice,” says Collins. “I have no idea whose interest it serves to be public”—except, she adds, for law enforcement and national-security investigators, who could find it “hugely useful.” The Trump administration’s immigration crackdown—one that has targeted politically active students here on visas—may give government investigators even more reasons to inspect public Venmo data. “I can think of a million ways, but I also don’t want to give them a million ideas about how to use this data,” says Reem Suleiman, U.S. advocacy lead with the Mozilla Foundation, the nonprofit behind the Firefox browser that has published multiple critiques of Venmo’s privacy settings. Venmo’s overall utility to government investigations remains unclear because PayPal has yet to follow the practice of other tech firms—even X, after a lapse following Elon Musk’s purchase of what was then Twitter—by publishing a transparency report documenting its responses to government queries. “Any company that holds sensitive user data should publish a thorough transparency report,” says Gennie Gebhart, managing director of technology at the San Francisco-based digital-liberties nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Users deserve a basic level of insight into how the company handles government requests for that kind of information.” A setting that’s not obvious to surface The setting can be easy to overlook because other payment apps don’t make your social graph public. Collins calls Venmo “a kind of strange outlier” in that respect. To check this in your own account: Open Venmo’s mobile app (the web interface doesn’t present this setting), tap the “Me” button at bottom right, tap the gear icon at top right, tap “Privacy,” tap “Friends List,” and select “Private.” Venmo didn’t even offer that privacy option for years; EFF called out the company for its absence in 2019, and only added it in 2021 after BuzzFeed News identified former president Joe Biden’s account. You can also choose not to appear in the friends lists of people who haven’t changed this default (and who may have only added you because they accepted Venmo’s invitation to import their entire contacts list). To do that, deselect “Appear in other users’ friends lists” beneath the friends-list publicity setting. This last privacy option is also less than self-evident, Suleiman admits: “I didn’t know that until I saw your questions.” Venmo did not answer a que

If it weren’t for Signal, Venmo might be the most infamous app of the Trump administration—and maybe the most beloved among journalists covering this White House.

That’s not because of any Trump staffer’s clumsiness, like the one that led national security advisor Mike Waltz to accidentally add Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg to a Signal chat group set up to discuss military strikes against Houthi terrorists. With the PayPal-owned payments app, the blame (or credit) goes to its default setting of making users’ friends lists public.

Vice President JD Vance ran afoul of that in July, when Wired identified the Venmo account of then-Sen. Vance (R-Ohio) and found 211 names on his friends list: a mix of tech executives, politicians, and journalists. Wired repeated the exercise in March for Waltz and found 328 Venmo friends covering a similar range of Washington society.

And on Tuesday, NOTUS reported that among “more than 50 current lawmakers, more than 20 former members of Congress, and more than three dozen current Trump administration officials and nominees” whose Venmo accounts the site identified over a week of research, “almost everyone had their friends lists open to the public.”

“It just keeps happening,” says Sara Collins, director of government affairs at the Washington-based digital-rights group Public Knowledge.

Who does this serve?

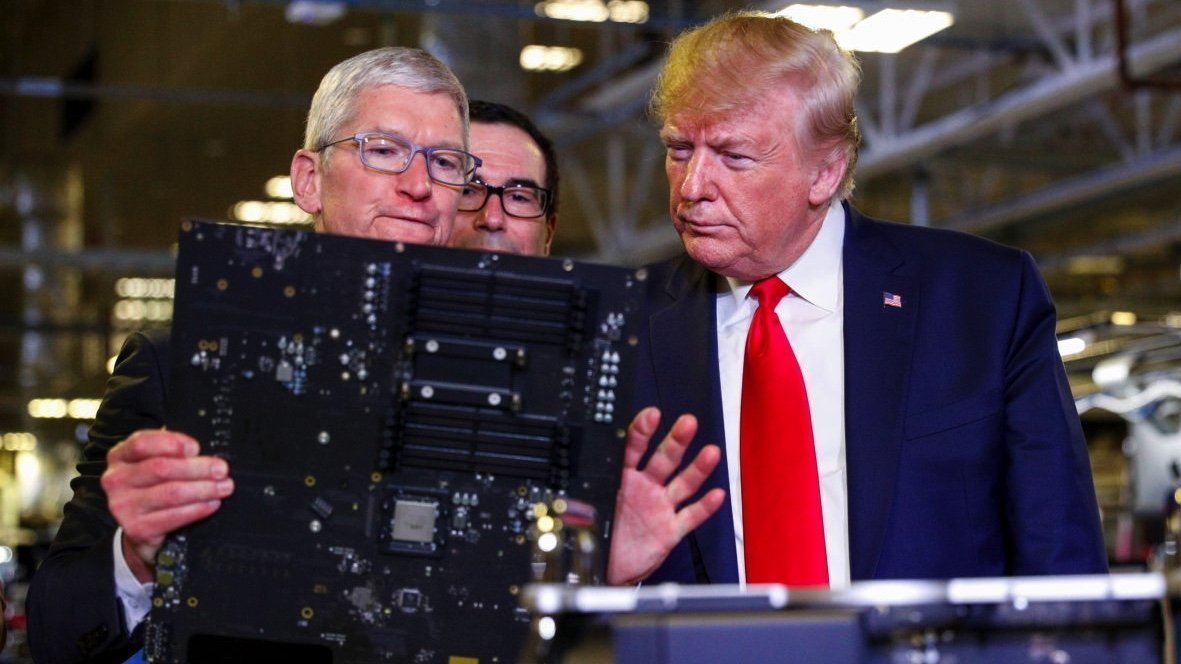

Venmo has historically defended this default as part of its social nature, much like it once made transactions public by default, despite vocal criticism. That payment publicity persisted even after Venmo settled a Federal Trade Commission investigation into that and other alleged deceptive conduct. Venmo didn’t remove the public transactions feed until 2021.

PayPal spokesperson Erin Mackey responded to Fast Company with a statement similar to what the company has offered in previous stories about Venmo privacy.

“The privacy and safety of Venmo users are top priorities,” she wrote. “Venmo provides in-app education and easy-to-use privacy settings to put users in control of who their friends lists are shared with or whether they appear in other users’ lists at all.”

Her statement ended with a line that departs slightly from prior responses: “We’re always listening to our customers to strengthen and evolve the Venmo platform while staying true to the social aspects they’ve come to know and love.”

Privacy advocates find Venmo’s public friends-list default nearly as troubling as the old public transactions feed.

“It’s not a good practice,” says Collins. “I have no idea whose interest it serves to be public”—except, she adds, for law enforcement and national-security investigators, who could find it “hugely useful.”

The Trump administration’s immigration crackdown—one that has targeted politically active students here on visas—may give government investigators even more reasons to inspect public Venmo data.

“I can think of a million ways, but I also don’t want to give them a million ideas about how to use this data,” says Reem Suleiman, U.S. advocacy lead with the Mozilla Foundation, the nonprofit behind the Firefox browser that has published multiple critiques of Venmo’s privacy settings.

Venmo’s overall utility to government investigations remains unclear because PayPal has yet to follow the practice of other tech firms—even X, after a lapse following Elon Musk’s purchase of what was then Twitter—by publishing a transparency report documenting its responses to government queries.

“Any company that holds sensitive user data should publish a thorough transparency report,” says Gennie Gebhart, managing director of technology at the San Francisco-based digital-liberties nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Users deserve a basic level of insight into how the company handles government requests for that kind of information.”

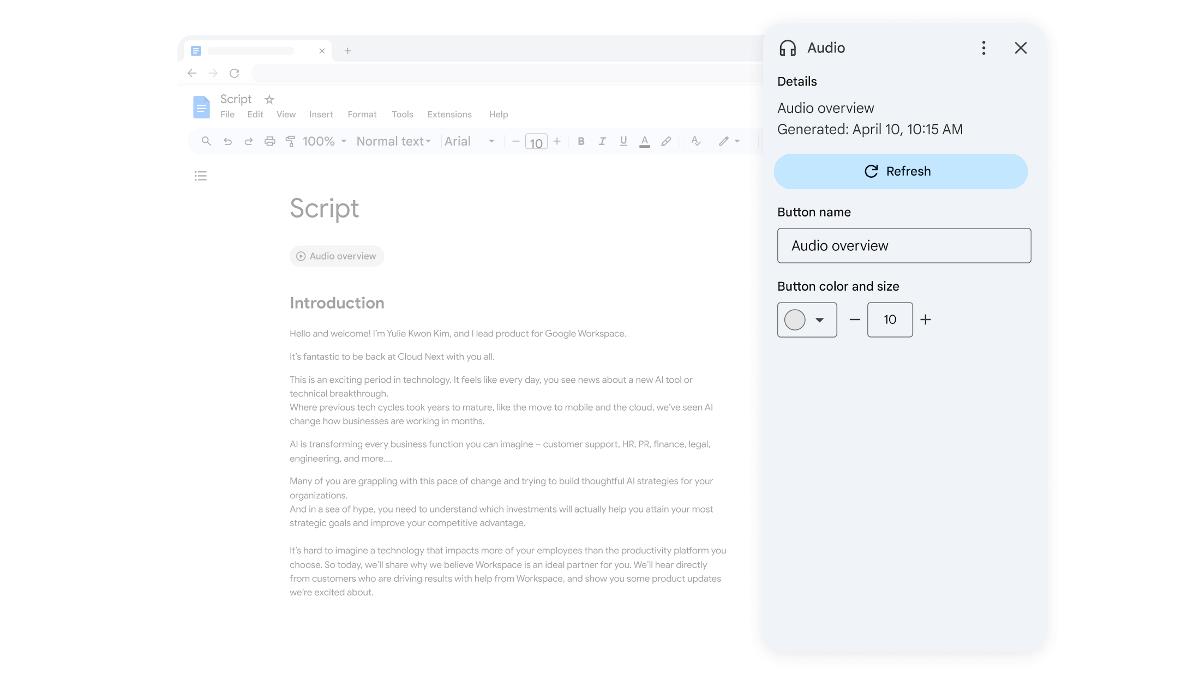

A setting that’s not obvious to surface

The setting can be easy to overlook because other payment apps don’t make your social graph public. Collins calls Venmo “a kind of strange outlier” in that respect.

To check this in your own account: Open Venmo’s mobile app (the web interface doesn’t present this setting), tap the “Me” button at bottom right, tap the gear icon at top right, tap “Privacy,” tap “Friends List,” and select “Private.”

Venmo didn’t even offer that privacy option for years; EFF called out the company for its absence in 2019, and only added it in 2021 after BuzzFeed News identified former president Joe Biden’s account.

You can also choose not to appear in the friends lists of people who haven’t changed this default (and who may have only added you because they accepted Venmo’s invitation to import their entire contacts list). To do that, deselect “Appear in other users’ friends lists” beneath the friends-list publicity setting.

This last privacy option is also less than self-evident, Suleiman admits: “I didn’t know that until I saw your questions.”

Venmo did not answer a question about how many of its users have changed their friends-list defaults.

“If public figures and elected officials with security teams can’t figure out Venmo’s settings, then we know that regular people just trying to pay for everything from rent to medical treatments are vulnerable, too,” says Gebhart.

Icky but not illegal

But while all of these experts judged Venmo’s conduct distasteful and unhelpful, they also suggested it wasn’t the makings of a legal case.

“Is it bad in the legal sense? No,” says Collins. “You put it in the terms of service, technically they’re notified.”

In late November, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau finalized a rule that would empower the agency to supervise digital-payment apps—including how they protect the privacy of their customers’ data.

But Republicans in Congress are moving quickly to quash that rule under the Congressional Review Act. The Senate has already voted to scrap it, with the House set to do so soon.

Outside Washington, the California Consumer Privacy Act provides much stronger privacy protections. But Collins says its provisions mainly focus on companies sending your data elsewhere.

“The California law is very concerned about selling data without your consent, or transferring data without your consent,” she explains. “There is no transfer here.”

The California Privacy Protection Agency, tasked with enforcing the CCPA, says it can’t comment on “potential or ongoing investigations.”

But in any case, state-level privacy laws offer no help to people living in other states. Which means Venmo’s lax defaults also expose a larger defect in the U.S.—the continued inability of Congress to pass a comprehensive federal privacy law, no matter how many examples surface to show one might help.

“To say that Venmo isn’t breaking the law here isn’t saying much, generally speaking, in the U.S.,” says Suleiman.

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

![From Accountant to Data Engineer with Alyson La [Podcast #168]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1744420903260/fae4b593-d653-41eb-b70b-031591aa2f35.png?#)

.png?#)

![Apple Watch SE 2 On Sale for Just $169.97 [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96996/96996/96996-640.jpg)

![Apple Posts Full First Episode of 'Your Friends & Neighbors' on YouTube [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96990/96990/96990-640.jpg)