Tariffs are bad news for batteries

Update: Since this story was first published in The Spark, our weekly climate newsletter, the White House announced that most reciprocal tariffs would be paused for 90 days. That pause does not apply to China, which will see an increased tariff rate of 125%. Today, new tariffs go into effect for goods imported into the…

Update: Since this story was first published in The Spark, our weekly climate newsletter, the White House announced that most reciprocal tariffs would be paused for 90 days. That pause does not apply to China, which will see an increased tariff rate of 125%.

Today, new tariffs go into effect for goods imported into the US from basically every country on the planet.

Since Donald Trump announced his plans for sweeping tariffs last week, the vibes have been, in a word, chaotic. Markets have seen one of the quickest drops in the last century, and it’s widely anticipated that the global economic order may be forever changed.

While many try not to look at the effects on their savings and retirement accounts, experts are scrambling to understand what these tariffs might mean for various industries. As my colleague James Temple wrote in a new story last week, anxieties are especially high in climate technology.

These tariffs could be particularly rough on the battery industry. China dominates the entire supply chain and is subject to monster tariff rates, and even US battery makers won’t escape the effects.

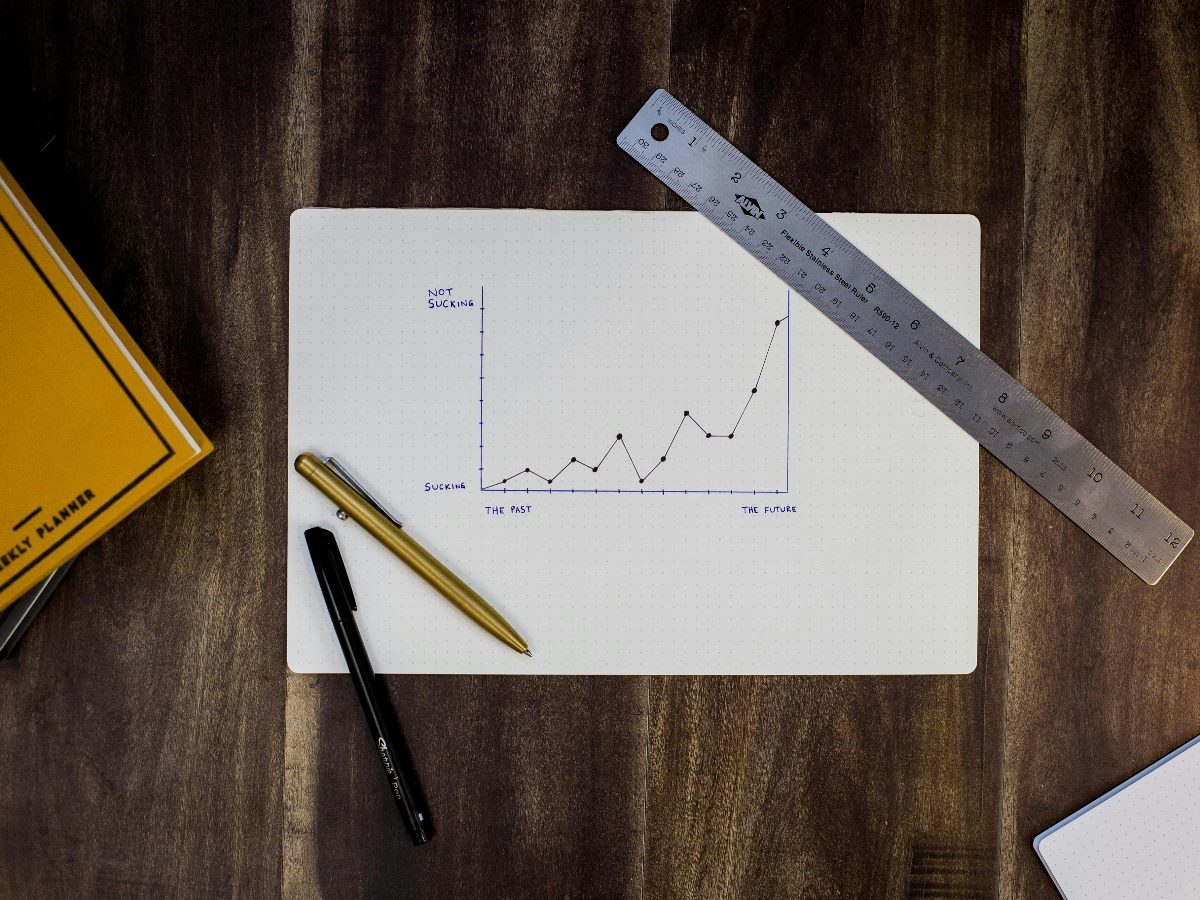

First, in case you need it, a super-quick refresher: Tariffs are taxes charged on goods that are imported (in this case, into the US). If I’m a US company selling bracelets, and I typically buy my beads and string from another country, I’ll now be paying the US government an additional percentage of what those goods cost to import. Under Trump’s plan, that might be 10%, 20%, or upwards of 50%, depending on the country sending them to me.

In theory, tariffs should help domestic producers, since products from competitors outside the country become more expensive. But since so many of the products we use have supply chains that stretch all over the world, even products made in the USA often have some components that would be tariffed.

In the case of batteries, we could be talking about really high tariff rates, because most batteries and their components currently come from China. As of 2023, the country made more than 75% of the world’s lithium-ion battery cells, according to data from the International Energy Agency.

Trump’s new plan adds a 34% tariff on all Chinese goods, and that stacks on top of a 20% tariff that was already in place, making the total 54%. (Then, as of Wednesday, the White House further raised the tariff on China, making the total 104%.)

But when it comes to batteries, that’s not even the whole story. There was already a 3.5% tariff on all lithium-ion batteries, for example, as well as a 7.5% tariff on batteries from China that’s set to increase to 25% next year.

If we add all those up, lithium-ion batteries from China could have a tariff of 82% in 2026. (Or 132%, with this additional retaliatory tariff.) In any case, that’ll make EVs and grid storage installations a whole lot more expensive, along with phones, laptops, and other rechargeable devices.

The economic effects could be huge. The US still imports the majority of its lithium-ion batteries, and nearly 70% of those imports are from China. The US imported $4 billion worth of lithium-ion batteries from China just during the first four months of 2024.

Although US battery makers could theoretically stand to benefit, there are a limited number of US-based factories. And most of those factories are still purchasing components from China that will be subject to the tariffs, because it’s hard to overstate just how dominant China is in battery supply chains.

While China makes roughly three-quarters of lithium-ion cells, it’s even more dominant in components: 80% of the world’s cathode materials are made in China, along with over 90% of anode materials. (For those who haven’t been subject to my battery ramblings before, the cathode and anode are two of the main components of a battery—basically, the plus and minus ends.)

Even battery makers that work in alternative chemistries don’t seem to be jumping for joy over tariffs. Lyten is a California-based company working to build lithium-sulfur batteries, and most of its components can be sourced in the US. (For more on the company’s approach, check out this story from 2024.) But tariffs could still spell trouble. Lyten has plans for a new factory, scheduled for 2027, that rely on sourcing affordable construction materials. Will that be possible? “We’re not drawing any conclusions quite yet,” Lyten’s chief sustainability officer, Keith Norman, told Heatmap News.

The battery industry in the US was already in a pretty tough spot. Billions of dollars’ worth of factories have been canceled since Trump took office. Companies making investments that can total hundreds of millions or billions of dollars don’t love uncertainty, and tariffs are certainly adding to an already uncertain environment.

We’ll be digging deeper into what the tariffs mean for climate technology broadly, and specifically some of the industries we cover. If you have questions, or if you have thoughts to share about what this will mean for your area of research or business, I’d love to hear them at casey.crownhart@technologyreview.com. I’m also on Bluesky @caseycrownhart.bsky.social.

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

![From Accountant to Data Engineer with Alyson La [Podcast #168]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1744420903260/fae4b593-d653-41eb-b70b-031591aa2f35.png?#)

.png?#)

![Apple Posts Full First Episode of 'Your Friends & Neighbors' on YouTube [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96990/96990/96990-640.jpg)

![Apple May Implement Global iPhone Price Increases to Mitigate Tariff Impacts [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96987/96987/96987-640.jpg)