Game of clones: Colossal’s new wolves are cute, but are they dire?

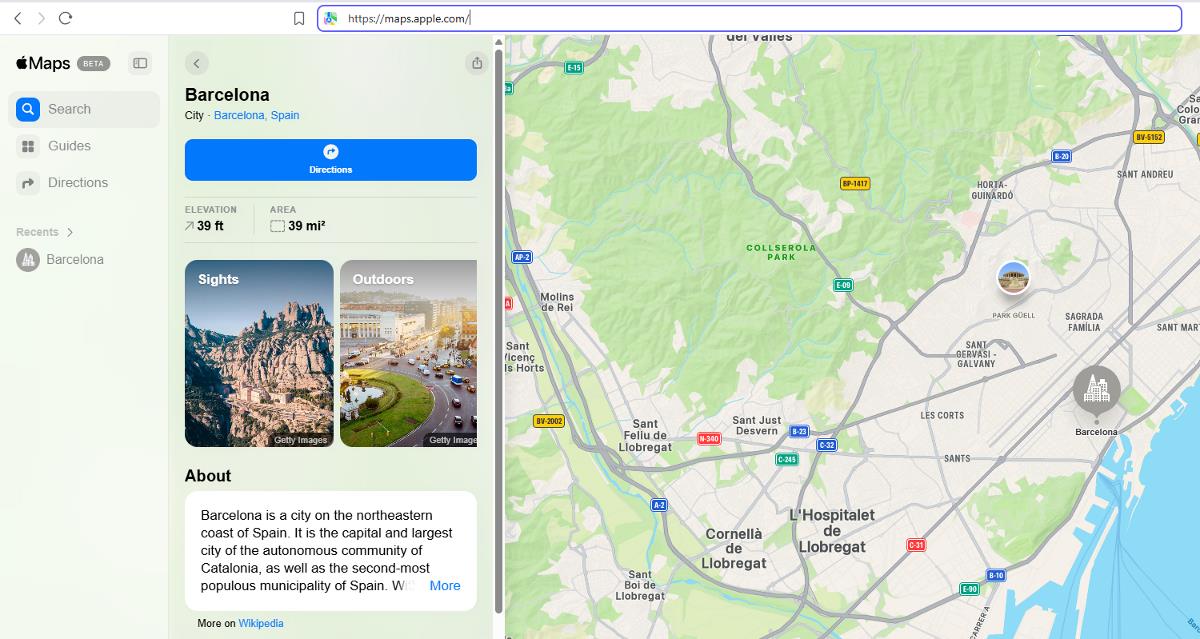

Somewhere in the northern US, drones fly over a 2,000-acre preserve, protected by a nine-foot fence built to zoo standards. It is off-limits to curious visitors, especially those with a passion for epic fantasies or mythical creatures. The reason for such tight security? Inside the preserve roam three striking snow-white wolves—which a startup called Colossal…

Somewhere in the northern US, drones fly over a 2,000-acre preserve, protected by a nine-foot fence built to zoo standards. It is off-limits to curious visitors, especially those with a passion for epic fantasies or mythical creatures.

The reason for such tight security? Inside the preserve roam three striking snow-white wolves—which a startup called Colossal Biosciences says are members of a species that went extinct 13,000 years ago, now reborn via biotechnology.

For several years now, the Texas-based company has been in the news for its plans to re-create woolly mammoths someday. But now it’s making a bold new claim—that it has actually “de-extincted” an animal called the dire wolf.

And that could be another reason for the high fences and secret location—to fend off scientific critics, some of whom have already been howling that the company is a “scam” perpetrating “elephantine fantasies” on the public and engaging in “pure hype.”

Dire wolves were large, big-jawed members of the canine family. More than 400 of their skulls have been recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits in California. Ultimately they were replaced by smaller relatives like the gray wolf.

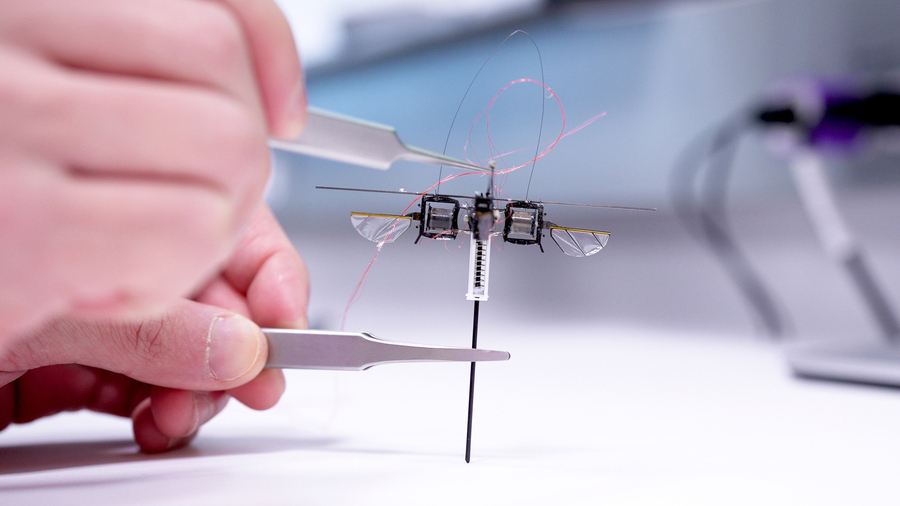

In its effort to re-create the animal, Colossal says, it extracted DNA information from dire wolf bones and used gene editing to introduce some of those elements into cells from gray wolves. It then used a cloning procedure to turn the cells into three actual animals.

The animals include two males, Romulus and Remus, born in October, and one female, Khaleesi, whose name is a reference to the TV series Game of Thrones, in which fictional dire wolves play a part.

Each animal, the company says, has 20 genetic changes across 14 genes designed to make them larger, change their facial features, and give them a snow-white appearance.

Some scientists reject the company’s claim that the new animals are a revival of the extinct creatures, since in reality dire wolves and gray wolves are different species separated by a few million of years of evolution and several million letters of DNA.

“I would say such an animal is not a dire wolf and it’s not correct to say dire wolves have been brought back from extinction. It’s a modified gray wolf,” says Anders Bergström, a professor at the University of East Anglia who specializes in the evolution of canines. “Twenty changes is not nearly enough. But it could get you a strange-looking gray wolf.”

Beth Shapiro, an expert on ancient DNA who is now on a three-year sabbatical from the University of California, Santa Cruz, as the company’s CSO, acknowledged in an interview that other scientists would bristle at the claim.

“What we’re going to have here is a philosophical argument about whether we should call it a dire wolf or call it something else,” Shapiro said. Asked point blank to call the animal a dire wolf, she hesitated but then did so.

“It is a dire wolf,” she said. “I feel like I say that, and then all of my taxonomist friends will be like, ‘Okay, I’m done with her.’ But it’s not a gray wolf. It doesn’t look like a gray wolf.”

Dire or not, the new wolves demonstrate that science is becoming more deft in its control over the genomes of animals—and point to how that skill could help in conservation. As part of the project, Colossal says, it also cloned several red wolves, an American species that’s the most endangered wolf in the world.

But that isn’t as dramatic as the supposed rebirth of an extinct animal with a large cultural following. “The motivation really is to develop tools that we can use to stop species from becoming extinct. Do we need ancient DNA for that? Maybe not,” says Shapiro. “Does it bring more attention to it so that maybe people get excited about the idea that we can use biotechnology for conservation? Probably.”

Secret project

Colossal was founded in 2021 after founder Ben Lamm, a software entrepreneur, visited the Harvard geneticist George Church and learned about a far-out and still mostly theoretical project to re-create woolly mammoths. The idea is to release herds of them in cold regions, like Siberia, and restore an ecological balance that keeps greenhouse gases trapped in the permafrost.

Lamm has unexpectedly been able to raise more than $400 million from investors to back the plan, and Forbes reported that he is now a multibillionaire, at least on paper, thanks to the $10 billion value assigned to the startup.

As Lamm showed he could raise money for Colossal’s ideas, it soon expanded beyond its effort to modify elephants. It publicly announced a bid to re-create the thylacine, a marsupial predator hunted to extinction, and then, in 2023, it started planning to resurrect the dodo bird—the effort that brought Shapiro to the company.

So far, none of those projects have actually resulted in a live animal.

Each faced dire practical issues. With elephants, it was that their pregnancies last two years, longer than those in any other species. Testing out mammoth designs would be impossibly slow. With the dodo bird, it was that no one has ever figured out how to genetically modify the pigeon, the most closely related species from which to craft a dodo via editing. One of Lamm’s other favorite targets—the Steller’s sea cow, which disappeared around 1770—has no obvious surrogate of any kind.

But bringing back a wolf was feasible. Over 1,500 dogs had been cloned, primarily by one company in South Korea. Researchers in Asia had even used dog eggs and dog mothers to produce both coyote and wolf clones. That’s not surprising, since all these species are closely enough related to interbreed.

“Just thinking about surrogacy for the dire wolf … it was like ‘Oh, yeah,’” recalls Shapiro. “Surrogacy there would be really straightforward.”

Dire wolves did present some new problems. One was the lack of any clear ecological purpose in reviving animals that disappeared during the Pleistocene epoch and are usually portrayed as ferocious predators with slavering jaws. “People have weird feelings about things that, you know, may or may not eat people or livestock,” Shapiro says.

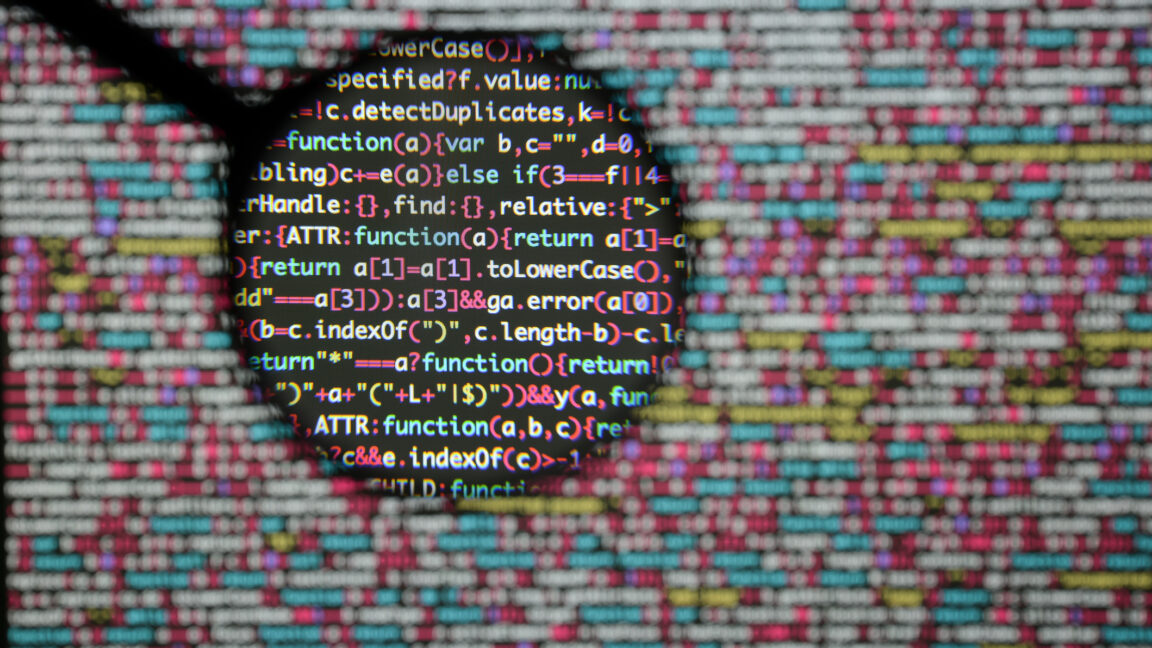

The technical challenge was there was still no accurate DNA sequence of a dire wolf. A 2021 effort to obtain DNA from old bones had yielded only a tiny amount, not enough to accurately decode the genome in detail. And without a detailed gene map, Colossal wouldn’t be able see what genetic differences they would need to install in gray wolves, the species they intended to alter.

Shapiro says she went back to museums, including the Idaho Museum of Natural History, and eventually got permission to cut off more bone from a 72,0000-year-old skull that’s on display there. She also got a tooth from a 13,000-year-old skull held in another museum. which she drilled into herself.

This time the bones yielded far more DNA and a much more complete gene map. A paper describing the detailed sequence is being submitted for publication; its authors include George R.R. Martin, the fantasy author whose books were turned into the HBO series Game of Thrones, and in which dire wolves appear as the characters’ magical companions.

In addition to placing dire wolves more firmly in the Canidae family tree (they’re slightly closer to jackals than to gray wolves, but more than 99.9% identical to both at a genetic level) and determining when dire wolves split from the pack (about 4 million years ago), the team also located around 80 genes where dire wolves seemed to be most different. If you wanted to turn a gray wolf into a dire wolf, this would be the obvious list to start from.

Crying wolf

Colossal then began the process of using base editing, an updated form of the CRISPR gene-modification technique, to introduce some of those exact DNA variations into blood cells of a gray wolf kept in its labs. Each additional edit, the company hoped, would make the eventual animal a little more dire-wolf-like, even it involved changing just a single letter of a gene.

Shapiro says all the edits involve “genetic enhancers,” bits of DNA that help control how strongly certain genes are expressed. These can influence how big animals grow, as well as affecting the shape of their ears, faces, and skulls. This tactic was not as dramatic as intervening right in the middle of a gene, which would change what protein is made. But it was less risky—more like turning knobs on an unfamiliar radio than cutting wires and replacing circuits.

That left the scientists to engineer into the animals what would become the showstopper trait—the dramatic white fur. Shapiro says the genome code indicated that dire wolves might have had light coats. But the specific pigment genes involved are linked to a risk of albinism, deafness, and blindness, and they didn’t want sick wolves.

That’s when Colossal opted for a shortcut. Instead of reproducing precise DNA variants seen in dire wolves, they disabled two genes entirely. In dogs and other species, the absence of those genes is known to produce light fur.

The decision to make the wolves white did result in dramatic photos of the animals. “It’s the most striking thing about them,” says Mairin Balisi, a paleontologist who studies dire wolf fossils. But she doubts it reflects what the animals actually looked like: “A white coat might make sense if you are in a snowy landscape, but one of the places where dire wolves were most abundant was around Los Angeles and the tar pits, and it was not a snowy landscape even in the Ice Age. If you look at mammals in this region today, they are not white. I am just confused by the declaration that dire wolves are back.”

Bergström also says he doesn’t think the edits add up to a dire wolf. “I doubt that 20 changes are enough to turn a gray wolf to a dire wolf. You’d probably need hundreds or thousands of changes—no one really knows,” he says. “This is one of those unsolved questions in biology. People argue [about] the extent to which many small differences make a species distinct, versus a small number of big-effect differences. Nobody knows, but I lean to the ‘many small differences’ view.”

Some genes have big, visible effects—changing a single gene can make a dog hairless, for instance. But it might be many more small changes that account for the difference in size and appearance between, say, a Great Dane and a Chihuahua. And that is just looks. Bergström says science has much less idea which changes would account for behavior—even if we could tell from a genome how an extinct animal acted, which we can’t.

“A lot of people are quite skeptical of what they are doing,” Bergström says of Colossal. “But I still think it’s interesting that someone is trying. It takes a lot of money and resources, and if we did have the technology to bring species back from extinction, I do think that would be useful. We drive species to extinction, sometimes very rapidly, and that is a shame.”

Cloning with dogs

By last August, the gray wolf cells had been edited, and it was time to try cloning those cells and producing animals. Shapiro says her company transferred 45 cloned embryos apiece into six surrogate dogs. That led to three pregnancies, from which four dogs were born. One of the four, Khaleesi’s sister, died 10 days after birth from an intestinal infection, deemed unrelated to the cloning process. “That was the only puppy that didn’t make it,” says Shapiro. Two other fetal clones were reabsorbed during pregnancy, which means they disintegrated, a fairly common occurrence in dogs.

These days the white wolves are able to freely roam around a large area. They don’t have radio collars, but they are watched by cameras and are trained to come to their caretakers to get fed, which offers a chance to weigh them as they cross a scale in the ground. The 10 staff members attending to them can see them up close, though they’re now too big to handle the way the caretakers could when they were puppies.

Whatever species these animals are, it’s not obvious what their future will be. They don’t seem to have a conservation purpose, and Lamm says he isn’t trying to profit from them.

“We’re not making money off the dire wolves. That’s not our business plan,” Lamm said in an interview with MIT Technology Review. He added that the animals would also not be put on display for the public, since “we’re not in the business of attractions.”

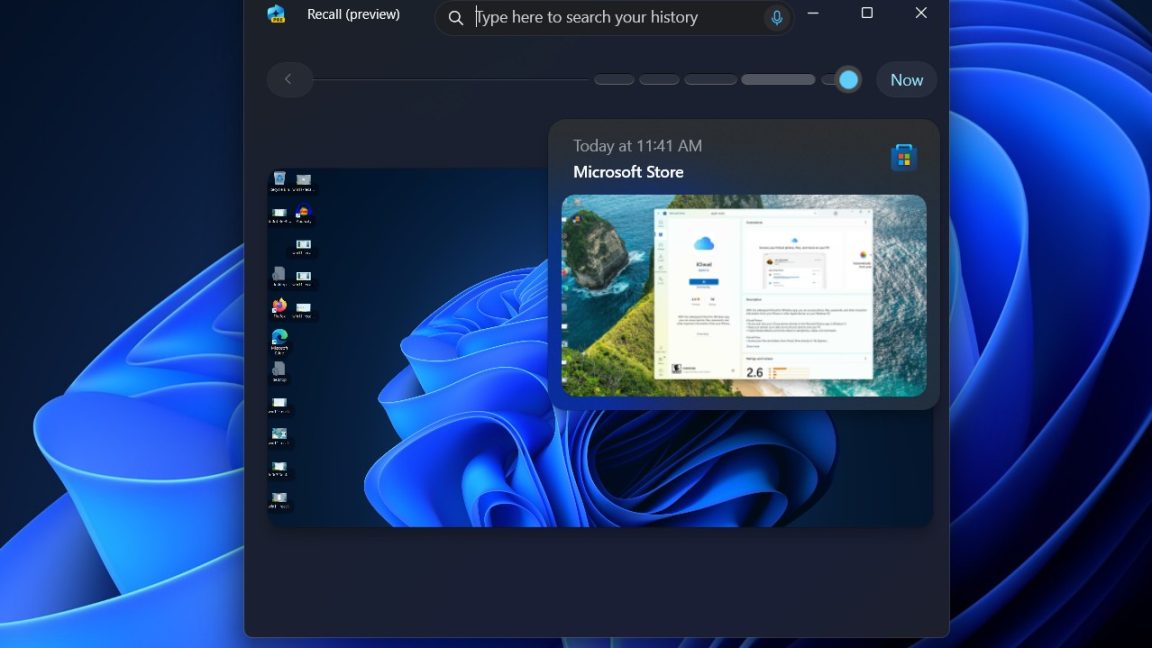

At least not in-person attractions. But every aspect of the project has been filmed, and in February, the company inked a deal to produce a docuseries about its exploits. That same month it also hired as its marketing chief a Hollywood executive who previously worked on big-budget “monster movies.”

And there are signs that de-extinction, in Colossal’s hands, has the potential to generate nearly out-of-control of attention, much like that scene in the original King Kong when the giant ape—captured by a filmmaker—breaks its chains under the flashes of the cameras.

For instance company’s first creation, mice with shaggy, mammoth-like hair, was announced only five weeks ago, yet there are already unauthorized sales of throw pillows and T-shirts (they read “Legalize Woolly Mice”), as well as some “serious security issues” involving unannounced visitors.

“We’ve had people show up to our labs because they want the woolly mouse,” Lamm says. “We’re worried about that from a security perspective [for] the wolves, because you’re going to have all the Game of Thrones people. You’re going to have a lot of people that want to see these animals.”

Lamm said that in light of his concerns about unruly fans, diagrams of the ecological preserve provided to the media had been altered so that no internet “sleuths” could use them to guess its location.

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

![From Accountant to Data Engineer with Alyson La [Podcast #168]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1744420903260/fae4b593-d653-41eb-b70b-031591aa2f35.png?#)

.png?#)

![Apple Posts Full First Episode of 'Your Friends & Neighbors' on YouTube [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96990/96990/96990-640.jpg)

![Apple May Implement Global iPhone Price Increases to Mitigate Tariff Impacts [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96987/96987/96987-640.jpg)