Improve Your Go Applications with Byte-level Data Optimization

Check out the full code referenced in this article on Github! Almost any application requires a way to store or transfer data. We often choose formats like JSON or YAML that are easy to read and modify. These formats are built to be generic to work in a variety of usecases, which means they are not heavily optimized for data size or fast encoding/decoding. I recently started making a sourdough starter. This requires dividing, feeding, and discarding every 12 or 24 hours. To ensure accuracy and consistency, I record the time and amounts for each feeding. This data is just numbers and time (which is also a number). Since I already had data optimizations on my mind, I saw a real-world usecase for implementing binary data optimizations. My goal is to create a hyper-specific and optimized time-series data. Rather than defaulting to JSON for storing data in a file, I will store it in a binary format. Intro to bytes Let's start with some basics about binary data in Go: The most basic types here are uint8 and byte, which are the same These contain 8 bits, which is 1 byte You might already be familiar with byte and []byte from encoding/decoding JSON or reading/writing files. This data type is use by Go for any filesystem interactions or encoding/decoding data. With 8 bits, we have 28 = 256 distinct values. Since we start at zero, we use the range 0-255. Each byte represents a number in this range and can be converted to characters from the extended ASCII table. The lower-case latin alphabet starts at 97 for 'a' and ends at 122 for 'z'. Therefore, []byte{104, 101, 108, 108, 111} is "hello" and 'b' - 'a' == 1 (see it for yourself!). Instead of using the ASCII table to convert bytes into human-readable strings, we can assign our own meaning to the data. The following JSON data holds two numbers and is 20 characters long, so it is 20 bytes: {"a": 114, "b": 125} A lot of this data is included just to make the data generically parseable by both humans and computers: ": marks the start and end of the string data type :: separates keys from values ,: separates one key-value pair from another {/}: shows the start and end of objects (space): just for human-readability A lot of this data is not strictly necessary if we are able to make specific assumptions about the data. After removing the brackets, quotes, and colons, we are left with: a255b127 Now this is only 8 bytes. However, it is no longer a flexible format. In order to be parseable, we have to introduce a few constraints: keys are always alphabetic (a-z, A-Z) and values are numeric 0-9. These constraints allow distinguishing the keys from values when parsing the data instead of relying on commas, colons, and quotation marks. Even this simple reduction introduces significant restrictions on what the data can represent, which is why JSON is so verbose. These numbers are each 3 characters since they are meant to be human-readable, so they use up 3 bytes of data. You might have noticed that these are within the 0-255 range, so they can be represented by a single byte each. As a human-readable character from the ASCII table, 114 is r and 125 is }. If we are able to assume that 'a' and 'b' are in order, then we can represent this data with only 2 bytes: r} (check it out here!) This data is no longer a generic key-value format and instead represents a specific type of data that just has two uint8 values. It also requires custom programming to encode and decode. In many usecases, these strict rules might not be worth the benefit. However, the tenfold reduction from 20 bytes to just 2 can result in significant storage and bandwidth savings. Now that we are familiar with byte and uint8, let's introduce a few more types: uint16: this is two bytes and holds up to 216-1 (65,535) uint32: 4 bytes, 232-1 (4,294,967,295) uint64: 8 bytes, 264-1 (18,446,744,073,709,551,615) We want to use the smallest type possible for each piece of data without compromising too much on the constraints. With such big jumps in size, there can be a lot of seemingly-wasted space. If we need a range of 0-300, we have to upsize from uint8 to uint16 which goes all the way to 65,535! It just uses one additional byte, so it's not a big deal. However, what if we could just use one additional bit to reach 300 instead of a whole byte? This, of course, is entirely possible. It requires more complex parsing using bit shifting and masking, but we'll get more into that later. Requirements In the previous section, we learned that we can significantly reduce the size of data by ditching JSON in favor of a more specific binary format. However, this requires a lot more knowledge about your data and the ability to follow strict constraints. It will increase the time it takes to program the encoding/decoding whenever new data fields are added. With JSON, you don't care if a number is int, int64, uint16, or any other value. In our case, these differ

Check out the full code referenced in this article on Github!

Almost any application requires a way to store or transfer data. We often choose formats like JSON or YAML that are easy to read and modify. These formats are built to be generic to work in a variety of usecases, which means they are not heavily optimized for data size or fast encoding/decoding.

I recently started making a sourdough starter. This requires dividing, feeding, and discarding every 12 or 24 hours. To ensure accuracy and consistency, I record the time and amounts for each feeding. This data is just numbers and time (which is also a number). Since I already had data optimizations on my mind, I saw a real-world usecase for implementing binary data optimizations. My goal is to create a hyper-specific and optimized time-series data. Rather than defaulting to JSON for storing data in a file, I will store it in a binary format.

Intro to bytes

Let's start with some basics about binary data in Go:

- The most basic types here are

uint8andbyte, which are the same - These contain 8 bits, which is 1 byte

You might already be familiar with byte and []byte from encoding/decoding JSON or reading/writing files. This data type is use by Go for any filesystem interactions or encoding/decoding data. With 8 bits, we have 28 = 256 distinct values. Since we start at zero, we use the range 0-255. Each byte represents a number in this range and can be converted to characters from the extended ASCII table. The lower-case latin alphabet starts at 97 for 'a' and ends at 122 for 'z'. Therefore, []byte{104, 101, 108, 108, 111} is "hello" and 'b' - 'a' == 1 (see it for yourself!). Instead of using the ASCII table to convert bytes into human-readable strings, we can assign our own meaning to the data.

The following JSON data holds two numbers and is 20 characters long, so it is 20 bytes:

{"a": 114, "b": 125}

A lot of this data is included just to make the data generically parseable by both humans and computers:

-

": marks the start and end of the string data type -

:: separates keys from values -

,: separates one key-value pair from another -

{/}: shows the start and end of objects -

(space): just for human-readability

A lot of this data is not strictly necessary if we are able to make specific assumptions about the data. After removing the brackets, quotes, and colons, we are left with:

a255b127

Now this is only 8 bytes. However, it is no longer a flexible format. In order to be parseable, we have to introduce a few constraints: keys are always alphabetic (a-z, A-Z) and values are numeric 0-9. These constraints allow distinguishing the keys from values when parsing the data instead of relying on commas, colons, and quotation marks. Even this simple reduction introduces significant restrictions on what the data can represent, which is why JSON is so verbose.

These numbers are each 3 characters since they are meant to be human-readable, so they use up 3 bytes of data. You might have noticed that these are within the 0-255 range, so they can be represented by a single byte each. As a human-readable character from the ASCII table, 114 is r and 125 is }. If we are able to assume that 'a' and 'b' are in order, then we can represent this data with only 2 bytes:

r}

This data is no longer a generic key-value format and instead represents a specific type of data that just has two uint8 values. It also requires custom programming to encode and decode. In many usecases, these strict rules might not be worth the benefit. However, the tenfold reduction from 20 bytes to just 2 can result in significant storage and bandwidth savings.

Now that we are familiar with byte and uint8, let's introduce a few more types:

-

uint16: this is two bytes and holds up to 216-1 (65,535) -

uint32: 4 bytes, 232-1 (4,294,967,295) -

uint64: 8 bytes, 264-1 (18,446,744,073,709,551,615)

We want to use the smallest type possible for each piece of data without compromising too much on the constraints. With such big jumps in size, there can be a lot of seemingly-wasted space. If we need a range of 0-300, we have to upsize from uint8 to uint16 which goes all the way to 65,535! It just uses one additional byte, so it's not a big deal. However, what if we could just use one additional bit to reach 300 instead of a whole byte? This, of course, is entirely possible. It requires more complex parsing using bit shifting and masking, but we'll get more into that later.

Requirements

In the previous section, we learned that we can significantly reduce the size of data by ditching JSON in favor of a more specific binary format. However, this requires a lot more knowledge about your data and the ability to follow strict constraints. It will increase the time it takes to program the encoding/decoding whenever new data fields are added. With JSON, you don't care if a number is int, int64, uint16, or any other value. In our case, these differences are very important and decisions between them must be data-driven. Let's get back to the sourdough use case and define some requirements:

- Sourdough starter measurement: this is the amount of existing starter that we are using. The process is started with just flour and water, so this measurement starts at 0. Once the process gets started, I'll be using 25-50 grams of starter.

- Flour measurement: we will always have a non-zero amount of flour, generally 50-100 grams.

- Water measurement: we will also always have non-zero amount of water. I aim to use the same amount of flour and water, but am sometimes off by a few grams so I can't always assume it's the same.

- Flour type: we can feed the starter with different types of flour: whole wheat, all purpose, bread, rye, or others

- Datetime: we want to know the time of feeding. Since feeding is a process that takes some time, we aren't going to pinpoint the time down to the second. Truncating to the minute is plenty. We could even do 5 minute granularity if that buys us any additional optimization. I don't need to backfill historical data, so dates after 2025 are fine.

Now that we have some base requirements, we can start designing and optimizing our data format.

Measurements

Since our measurements all have similar constraints and numeric values are easy, let's start there.

I follow a low-waste recipe that uses small amounts of each ingredient, so we can easily use uint8 which maxes out at 255 grams. If we need to allow for a larger-scale bakery to use this data format, we can measure in decagrams or kilograms which gives us up to 2,550 or 255,000 grams but loses some granularity. A uint16 would give us a much larger range at the cost of 1 additional byte, so this is an easy change to make if the requirements for measurements were different. In this case, let's stick with uint8.

Can we simplify it further? Ratios are big in the world of sourdough baking, so maybe we can use them to reduce data sizes. Unfortunately, since we start with 0 starter and non-zero water/flour, a ratio won't work here. Water and flour are usually in a 1:1 or 1:2 ratio which could easily be stored with a single bit. However, this doesn't account for inaccuracy in measurements. I often add a little too much water or a little too much flour so the values are slightly different and I want to record that discrepancy. Additionally, I might want to experiment with different ratios like 1:1.5 or others, so this constraint doesn't fit.

Since we are already using 1 byte with the uint8, any additional reductions introduce a lot of complexity. Taking off a single bit gives us up to 127g, which is enough for the scale I am operating at, but 1 bit isn't worth the effort and results in the same on-disk space in the end since filesystems operate at the byte-level. Removing another bit and limiting our measurements to 63g still works for my very small scale, but sometimes I might want to make a larger batch of bread that doesn't fit in this constraint. Therefore, I'll stick with the uint8.

In code, this looks like:

buf := make([]byte, dataSize)

// encode to bytes

buf[0] = data.StarterGrams

buf[1]] = data.FlourGrams

buf[2] = data.WaterGrams

// decode bytes

data.StarterGrams = in[0]

data.FlourGrams = in[1]

data.WaterGrams = in[2]

Flour type

Starters can be fed with different types of flour which will impact how it grows. I am only aware of four relevant types: all purpose, whole wheat, bread, rye, but I am sure there are more. In Go, enums are often created using iota constants, which is an untyped integer. Each flour type can be assigned to a different integer value, so the type used will determine the range of values.

uint8 allows up to 255 which goes way beyond the five types. 23 has the range 0-7 which fits our 5 types, but is not very extensible if I learn about and start using new types. However, Go does not allow having variables or data smaller than a byte and neither do filesystems. We would have to pad out the remaining 5 bits with zeros and lose any benefit from the optimization. Therefore, we'll stick with the uint8, but keep 23 in mind.

Once again, the code is very simple:

// encode

buf[3] = byte(data.FlourType)

// decode

data.FlourType = FlourType(in[3])

Time

Go represents time with a struct that can easily be converted to seconds since an epoch (January 1, 1970 UTC). This is an int64 which is already compact at 8 bytes, but we can do better. 1,745,010,295 represents a timestamp in April 2025 which is less than the max uint32 (4,294,967,295). Since we don't care about seconds, we can convert this to minutes by dividing by 60: 29,083,504. This is already way smaller, but doesn't fit in our next size down (uint16). Since we don't need historical data, we can count the minutes since 2025 as the epoch instead of 1970. That 55 year difference converts to 28,908,000 minutes. While this is a large number, it is less than 1% of uint32's max. This optimization would just extend our max date by 55 years which is not important here.

Since this data is sequential in a time-series, we can optimize by using time offsets. The initial time is recorded using uint32 (4 bytes) and then each new data point stores an amount of time passed since the previous. The options for recording the offsets are:

-

uint8: maxes at 255 minutes, or 10.625 hours which is not enough for a 12-24 hour feeding interval -

uint16: significantly larger range of 0-65,535 minutes, or about 45 days

uint16 is a good choice since the starter can go for a week or more without feeding if it's refrigerated. There is a low risk of overflowing the 45 days, but it's not an excessively large limit.

The flaw with this implementation is that we always have to read our data from the beginning if we want to see the latest date. Also, the first entry is a different format which can be challenging to deal with. There is no way to randomly-access data with this optimization. This would significantly reduce the data size from 4 bytes to only 2, so it may be worth it, especially since parsing the data should be fast. This flaw could also be mitigated by saving data ranges in chunks, where a full timestamp is written after every N data points. This would be interesting to implement, but I am focusing on parsing individual data points for now.

There's one more option that I am considering. Take a look at this simple datetime: 2025-04-16 12:00. Breaking it down, we have:

-

Year (2025+): This is the largest number, but we do not plan to insert historical data, so we can assume it starts at 2025 and only record an offset from there. Using a

uint8gives us 255 years before it overflows -

Month (1-12): Our smallest data type,

uint8goes up to 255 which is way overkill. Half of that, 24, allows 0-15, so we can use 4 bits instead -

Day (1-31): Once again,

uint8is overkill for this. 25 allows 0-31 so it's a perfect fit - Hour (1-24): This is another case for 25

- Minute (0-60): This one needs 26, which is 0-63

Overall, we have 8 + 4 + 5 + 5 + 6 = 28 bits. This is another partial-byte idea that requires padding out to 32 bits/4 bytes anyways. Instead of padding with empty bits, the 3-bit option for flour type could be stored in those extra bits. This requires more complex bitwise operations to encode and decode, so I'll put it on the backburner for now.

Ultimately, I'll move forward with the simplest option first: uint32 for a minutes epoch instead of the usual seconds epoch. This approach has a significant edge for its simplicity and already halves the data size compared to int64. Keep the other ideas in mind for future optimizations.

Since we have multiple bytes now, the code is a bit different:

// encode

// convert to minutes since epoch, then write across 4 bytes

minutes := sd.Time.Unix()/60

binary.LittleEndian.PutUint32(buf[4:], uint32(minutes))

// decode

// read 4 bytes into a uint32 and convert back to epoch time

minutes := binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(in[4:])

sd.Time = time.Unix(int64(minutes)*60, 0).UTC()

Putting it all together

Time: 4 bytes (32 bits)

Measurements: 1 byte each, for a total of 3 bytes (24 bits)

FlourType: 1 byte (8 bits)

Total: 8 bytes (64 bits)

This conveniently fits in a single int64! However, [8]byte is more practical and efficient to work with. If I feed my sourdough starter twice daily for 100 years, that's just 570.3 KiB!

- Two data points per day is 2 * 365 = 730 records each year

- Each record is 8 bytes total, so 8 * 730 = 5,840 bytes per year

- After 100 years, its 584,000 bytes

- 584,000 / 1,024 ~= 570.3 KiB

I averaged out the size of 100,000 JSON data points to be about 97.71074 bytes each. The JSON representation of this data would be 730 * 100 * 97.71074 = 7,132,884.02 bytes ~= 6.8 MiB! While this data is still pretty small, it significantly larger than the binary representation of data.

Here is the final code responsible for these optimizations:

const dataSize = 8

type Data struct {

Time time.Time

StarterGrams uint8

FlourGrams uint8

WaterGrams uint8

FlourType FlourType

}

func (sd *Data) MarshalBinary() ([]byte, error) {

buf := make([]byte, dataSize)

// The uint8 fields can be directly insert to the byte slice

buf[0] = sd.StarterGrams

buf[1] = sd.FlourGrams

buf[2] = sd.WaterGrams

buf[3] = byte(sd.FlourType)

// Convert Unix time to minutes

minutes := sd.Time.Unix()/60

// The encoding/binary library can be used to insert the uint32

// time representation into the byte slice

binary.LittleEndian.PutUint32(buf[4:], uint32(minutes))

return buf, nil

}

func (s *Data) UnmarshalBinary(in []byte) error {

// Simply read uint8 fields from the byte slice in the correct order

sd.StarterGrams = in[0]

sd.FlourGrams = in[1]

sd.WaterGrams = in[2]

sd.FlourType = FlourType(in[3])

// Get uint32 minutes from the byte slice and convert back into time.Time

minutes := binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(in[4:])

sd.Time = time.Unix(int64(minutes)*60, 0).UTC()

return nil

}

Similar to marshal and unmarshal in encoding/json, implementing MarshalBinary and UnmarshalBinary enables encoding and decoding with the encoding/gob package. This is useful when a struct is part of another data structure, such as a slice. With these implemented, we can encode and decode binary data with the same convenience as JSON.

Go's built-in benchmarking provides a way to test the performance compared to JSON. In order to make the tests more fair, the init function is used to generate a slice of data:

var data []sourdough.Data

func init() {

size := 10_000

data = make([]sourdough.Data, size)

for i := 0; i < size; i++ {

data[i].Time = time.Date(

2025+rand.Intn(50), // Year: 2025 + up to 49 years

time.Month(rand.Intn(12)+1), // Month

rand.Intn(28)+1, // Day

rand.Intn(24)+1, // Hour

rand.Intn(60)+1, // Minute

0, 0, time.UTC,

)

data[i].StarterGrams = uint8(rand.Intn(256))

data[i].FlourGrams = uint8(rand.Intn(256))

data[i].WaterGrams = uint8(rand.Intn(256))

data[i].FlourType = sourdough.FlourType(rand.Intn(int(sourdough.FlourTypeBread + 1)))

}

}

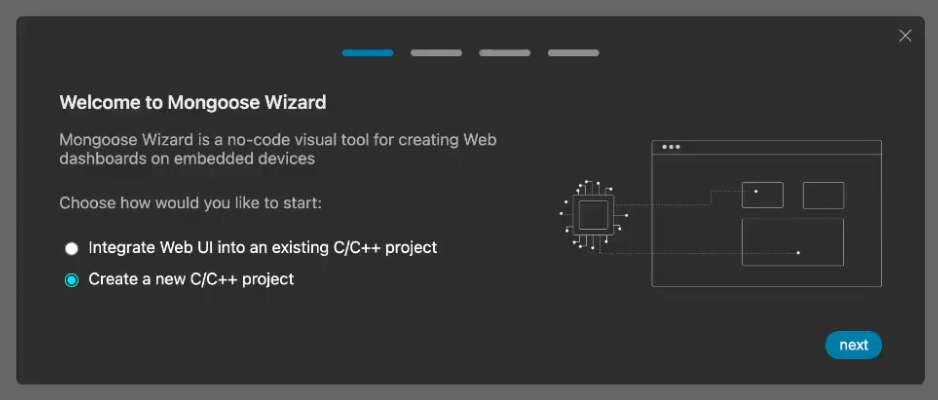

The benchmarks for each implementation encode the data to bytes, then decode it back into a new slice of data. Finally, it is compared to the initial data to make sure it encoded and decoded successfully. Here are the results of the benchmark:

> go test -bench . -benchmem

goos: darwin

goarch: arm64

pkg: sourdough

cpu: Apple M3 Pro

BenchmarkJSON-11 50 23172882 ns/op 5747196 B/op 30054 allocs/op

BenchmarkBinaryUnixMinute-11 1000000000 0.01411 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkBinaryUnix-11 1000000000 0.01398 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

BenchmarkBinaryCompact-11 1000000000 0.01439 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

PASS

ok sourdough 2.433s

The first number in each benchmark row is the total number of times that the test was executed. By default, Go will limit the benchmark time to 1 second and run as many iterations of each test as it takes to fill this time. It looks like each of the binary tests max out at 1,000,000,000 iterations while the JSON test only runs a miniscule 50 times. The next value shows how many nanoseconds each iteration of the benchmark took to execute, which shows a clear advantage to the binary implementations. Finally, we can see the memory usage and allocations for the tests which is another big win for binary.

There are slight variances each time the benchmark is executed, so I encourage you to try it for yourself.

In this output, there are a few additional tests different binary implementations:

-

BenchmarkBinaryUnixMinuteusesuint32for minutes since the epoch -

BenchmarkBinaryUnixusesuint64for seconds since the epoch (time.Unix()) -

BenchmarkBinaryCompactuses a more compact encoding that we'll explore in the next section

The benchmark results for the different binary implementations are too close to call, so comparing these will come down to storage size rather than performance.

Overall, each of the binary implementations is way faster than JSON, uses less memory, and much less storage space. In the short test execution time, the binary benchmarks had 20,000,000 times more iterations than the JSON benchmark. To be clear, that's 20,000,000 times the number of iterations, not 20,000,000 more iterations. Then, each JSON operation takes 23,172,882 nanoseconds, or about 23ms. The binary operations are taking less than a nanosecond, which is incomprehensible and 1,639,977,495 times faster than the JSON. We can scale things up a bit and run 1000 executions of encoding for each implementation. This takes over 9 seconds for JSON and about 477 milliseconds for the binary data. 9 seconds is definitely a loading time that you notice, while 477ms is more tolerable.

Optimizing it further

Benchmarking already revealed that this doesn't have an impact on speed, but let's look back at the partial-byte optimizations for time (28 bits) and flour type (3 bits). Speed isn't everything, so we'll focus on how this can reduce the data size. Since there are 31 bits, we can extend the flour type to use 4 bits and have an even 32 (4 bytes). Now the uint32 size that previously held the time can hold up to 16 different flour types!

This reduces the overall size of data to 7 bytes instead of 8. This small difference is more significant than it initially seems. The 12.5% reduction in size results in 71.3 KiB savings over 100 years. More importantly, it's an interesting technique to learn about and implement.

Sharing a byte

The tricky part now is implementing the shared bytes.

4 bytes look like this:

0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

Zoomed in a bit more:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000

Now we need to assign some meaning to these bits.

00000000 0000 0000 0 00000 00 0000 0000

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

- A - Year offset (8 bits, 0-255): this is the entire first byte

- B - Month (4 bits, 0-15): this is half of the second byte

- C - Day (5 bits, 0-31): the other half of the second byte + one bit from the third byte

- D - Hour (5 bits, 0-31): the next five bits of the third byte

- E - Minute (6 bits, 0-63): two remaining bits of the third byte and first half of the last byte

- F - Flour Type (4 bits, 0-15): last four bits of the fourth byte

This is how we can access data within the same byte, or even as parts of multiple bytes. When you have a normal 8-bit uint8, it may look something like this when converted to binary representation: 11110000. This is the base ten number 240. This byte can be split into two parts (nibbles): 1111 and 0000, or 15 and 0 respectively. How can we extract these values? In Go, the smallest integer is uint8, so these would still have to be represented by 8 bits: 00001111 and 00000000. This is where bit shifting and masking come in:

-

11110000can be changed to00001111by shifting the 1's to the right by 4 positions:

var x uint8 = 0b11110000 fmt.Println(x >> 4) -

11110000can be changed to00000000by replacing the 1's with 0's by masking

var x uint8 = 0b11110000 fmt.Println(x & 0b00001111)- This works by performing a bitwise "and" operation on the data. We put a

1in the positions that we want to keep since1 & 1 == 1and1 & 0 == 0. Anywhere on the original data with a 0 will remain 0, and anywhere with a 1 will remain 1

- This works by performing a bitwise "and" operation on the data. We put a

-

If we want the middle 4 bits (

1100, or 12), we need to combine shifting and masking:

var x uint8 = 0b11110000 fmt.Println((x & 0b00_1111_00) >> 2)- This works by "selecting" the middle 4 bits with the mask, and then shifts them over to be the right-most bits

Check out this simple example. This isn't intended to be an in-depth tutorial of bitwise operations. If this is a new concept for you, I encourage you to continue researching and learning about it.

Now we need to apply these techniques to extract six different pieces of data from four bytes.

Here's how we can encode the datetime and flour type into four bytes:

func encodeCompactDateAndFlourType(sd Data) []byte {

// Year is simply one byte/uint8

year := uint8(sd.Time.Year() - 2025)

// Month is the left four bits of the 2nd byte

month := uint8(sd.Time.Month() << 4)

// Day is 5 bits split across the 2nd and 3rd bytes

day := sd.Time.Day()

dayPart1 := (uint8(day) & 0b000_1111_0) >> 1

dayPart2 := (uint8(day) & 0b0000000_1) << 7

// Hour is 5 bits in the middle of the 3rd byte

hour := uint8(sd.Time.Hour()) << 2

// Minute is 6 bits split across the 3rd and 4th bytes

minute := sd.Time.Minute()

minutePart1 := (uint8(minute) & 0b00_11_0000) >> 4

minutePart2 := (uint8(minute) & 0b0000_1111) << 4

// FlourType is just the final 4 bits

flourType := uint8(sd.FlourType) & 0b0000_1111

return []byte{

year,

month | dayPart1,

dayPart2 | hour | minutePart1,

minutePart2 | flourType,

}

}

It can then be decoded from bytes with this function, which simply reverses the previous bitwise operations:

func decodeCompactDateAndFlourType(data []byte, sd *Data) {

year := int(data[0]) + 2025

month := data[1] >> 4

dayPart1 := (data[1] << 1) & 0b000_1111_0

dayPart2 := (data[2] >> 7) & 0b0000000_1

day := dayPart1 | dayPart2

hour := (data[2] >> 2) & 0b000_11111

minutePart1 := (data[2] << 4) & 0b00_11_0000

minutePart2 := (data[3] >> 4) & 0b0000_1111

minute := minutePart1 | minutePart2

sd.Time = time.Date(year, time.Month(month), int(day), int(hour), int(minute), 0, 0, time.UTC)

sd.FlourType = FlourType(data[3] & 0b0000_1111)

}

While this code isn't the most complex, it's generally unapproachable for a lot of developers. Even when revisiting this to write about it, I had to spend some extra time figuring out how it works. All of this saves just one byte of data. At a large scale, this can save a decent amount of storage space, but comes at a cost of maintainability.

The previous solution that operated at the byte-level already provided a significant boost in performance and reduced storage space with a minimal impact to maintainability. It's usually not worth the effort to take this next step to the bit level. If there's a specific use case to store many 4-bit values, that is a case where bit-level operations would be simple and halves the data size compared to uint8.

Conclusion

In this exploration of data optimization, we learned about the different data types and how they can be manipulated to represent more than just basic numbers. Well-defined constraints are the key to optimizing data. If we know exactly what our data can look like and how it needs to be used, we can make informed decisions about how to represent that data.

The tradeoff is that this format is very rigid and challenging to modify. Also, it cannot be parsed outside of our program, so debugging and analyzing data becomes more difficult.

Now what if you wanted to balance flexibility, extensibility, and performance? This is the reason Protobuf exists. It uses a schema/definition for structured data and generates the code for encoding and decoding it. This allows the defined types to be compatible with different progamming languages and spares engineers from low-level programming. I created a proto definition for this data and added another benchmark. There are a few small tradeoffs here. First, the smallest integer is uint32, so the protobuf data isn't quite as compact as the custom solution. Additionally, it is slightly slower in the benchmark, but when we are looking at thousandths of a nanosecond, the difference isn't significant.

If you have the ability to use rigidly-structured data, I recommend using Protobuf before rolling your own custom binary solution. However, it's still good to learn about how it works from scratch, and you can still squeeze out more optimizations if it's really necessary. Low-level concepts like binary data and bytes can be challenging to work with, but understanding them can increase your understanding of how programs work and how memory impacts performance. Knowing how things work will give you more tools and options for improving performance and efficiency of your applications.

![[The AI Show Episode 146]: Rise of “AI-First” Companies, AI Job Disruption, GPT-4o Update Gets Rolled Back, How Big Consulting Firms Use AI, and Meta AI App](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20146%20cover.png)

![[FREE EBOOKS] Offensive Security Using Python, Learn Computer Forensics — 2nd edition & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Ditching a Microsoft Job to Enter Startup Purgatory with Lonewolf Engineer Sam Crombie [Podcast #171]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1746753508177/0cd57f66-fdb0-4972-b285-1443a7db39fc.png?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-xl.jpg)

![New iPad 11 (A16) On Sale for Just $277.78! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97273/97273/97273-640.jpg)

![Apple Foldable iPhone to Feature New Display Tech, 19% Thinner Panel [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97271/97271/97271-640.jpg)