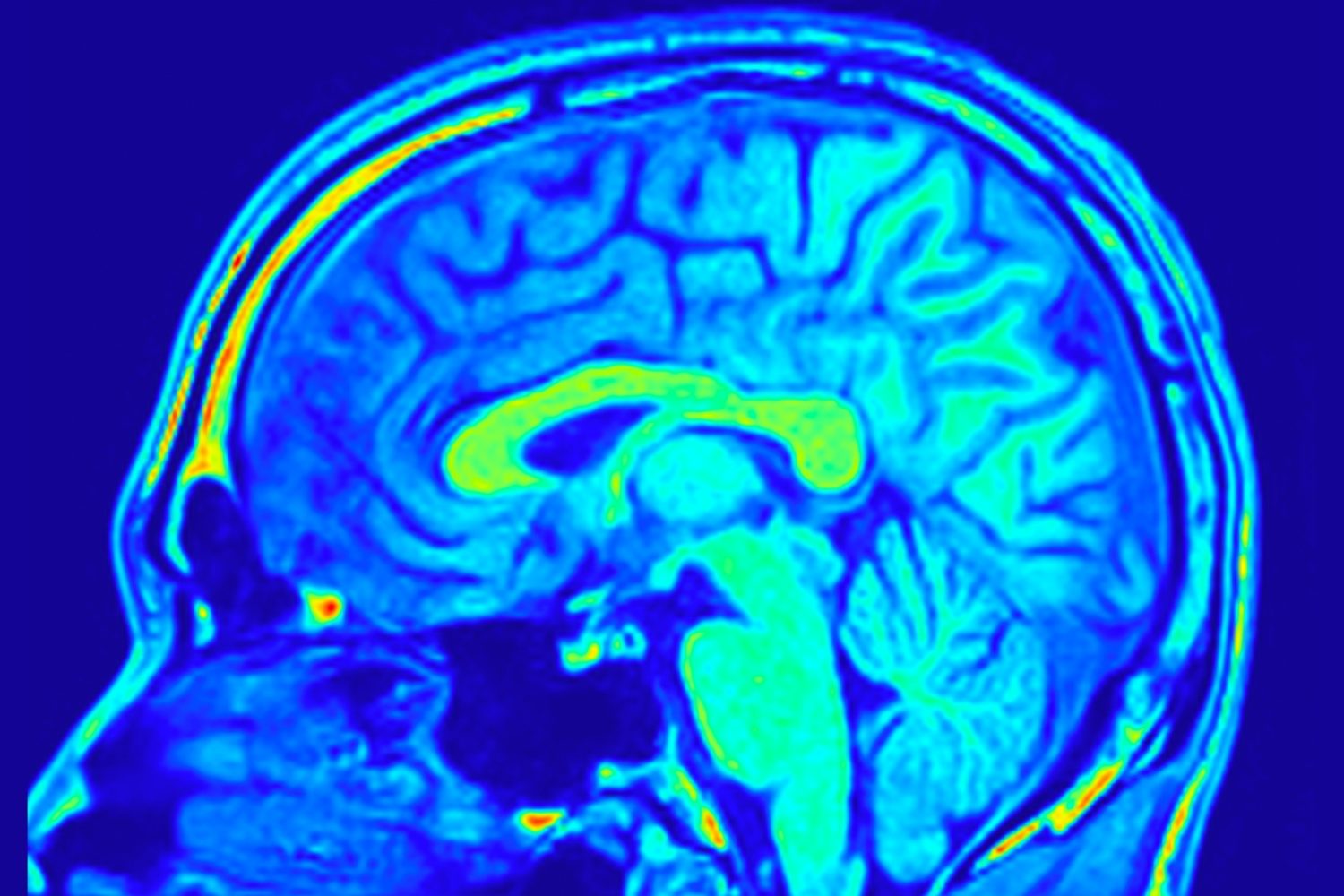

This patient’s Neuralink brain implant gets a boost from generative AI

Last November, Bradford G. Smith got a brain implant from Elon Musk’s company Neuralink. The device, a set of thin wires attached to a computer about the thickness of a few quarters that sits in his skull, lets him use his thoughts to move a computer pointer on a screen. And by last week he…

Last November, Bradford G. Smith got a brain implant from Elon Musk’s company Neuralink. The device, a set of thin wires attached to a computer about the thickness of a few quarters that sits in his skull, lets him use his thoughts to move a computer pointer on a screen.

And by last week he was ready to reveal it in a post on X.

“I am the 3rd person in the world to receive the @Neuralink brain implant. 1st with ALS. 1st Nonverbal. I am typing this with my brain. It is my primary communication,” he wrote. “Ask me anything! I will answer at least all verified users!”

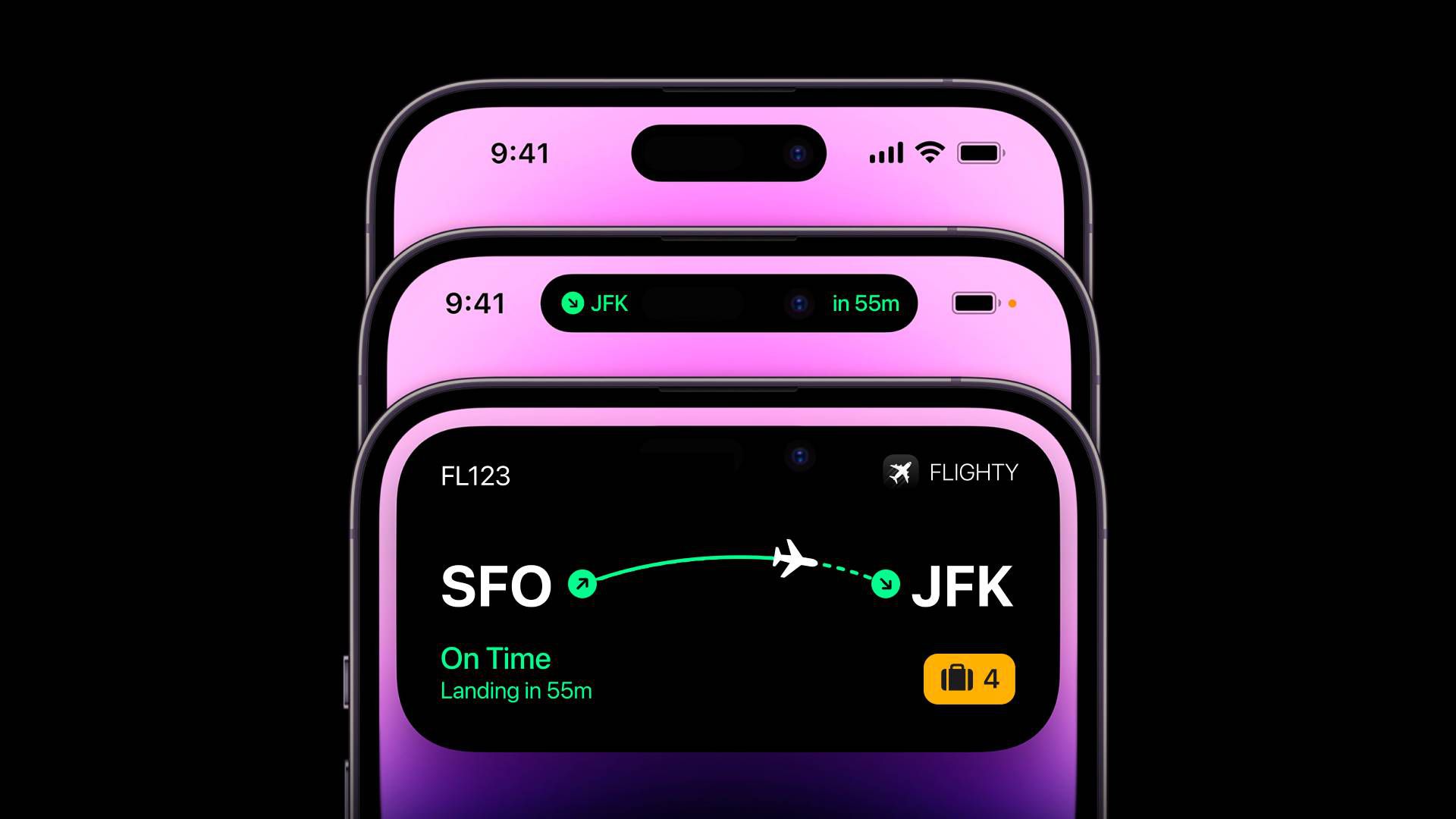

Smith’s case is drawing interest because he’s not only communicating via a brain implant but also getting help from Grok, Musk’s AI chatbot, which is suggesting how Smith can add to conversations and drafted some of the replies he posted to X.

The generative AI is speeding up the rate at which he can communicate, but it also raises questions about who is really talking—him or Musk’s software.

“There is a trade-off between speed and accuracy. The promise of brain-computer interface is that if you can combine it with AI, it can be much faster,” says Eran Klein, a neurologist at the University of Washington who studies the ethics of brain implants.

Smith is a Mormon with three kids who learned he had ALS after a shoulder injury he sustained in a church dodgeball game wouldn’t heal. As the disease progressed, he lost the ability to move anything except his eyes, and he was no longer able to speak. When his lungs stopped pumping, he made the decision to stay alive with a breathing tube.

Starting in 2024, he began trying to get accepted into Neuralink’s implant study via “a campaign of shameless self-promotion,” he told his local paper in Arizona: “I really wanted this.”

The day before his surgery, Musk himself appeared on a mobile phone screen to wish Smith well. “I hope this is a game changer for you and your family,” Musk said, according to a video of the call.

“I am so excited to get this in my head,” Smith replied, typing out an answer using a device that tracks his eye movement. This was the technology he’d previously used to communicate, albeit slowly.

Smith was about to get brain surgery, but Musk’s virtual appearance foretold a greater transformation. Smith’s brain was about to be inducted into a much larger technology and media ecosystem—one of whose goals, the billionaire has said, is to achieve a “symbiosis” of humans and AI.

Consider what unfolded on April 27, the day Smith announced on X that he’d received the brain implant and wanted to take questions. One of the first came from “Adrian Dittmann,” an account often suspected of being Musk’s alter ego.

Dittmann: “Congrats! Can you describe how it feels to type and interact with technology overall using the Neuralink?”

Smith: “Hey Adrian, it’s Brad—typing this straight from my brain! It feels wild, like I’m a cyborg from a sci-fi movie, moving a cursor just by thinking about it. At first, it was a struggle—my cursor acted like a drunk mouse, barely hitting targets, but after weeks of training with imagined hand and jaw movements, it clicked, almost like riding a bike.”

Another user, noting the smooth wording and punctuation (a long dash is a special character, used frequently by AIs but not as often by human posters), asked whether the reply had been written by AI.

Smith didn’t answer on X. But in a message to MIT Technology Review, he confirmed he’d used Grok to draft answers after he gave the chatbot notes he’d been taking on his progress. “I asked Grok to use that text to give full answers to the questions,” Smith emailed us. “I am responsible for the content, but I used AI to draft.”

The exchange on X in many ways seems like an almost surreal example of cross-marketing. After all, Smith was posting from a Musk implant, with the help of a Musk AI, on a Musk media platform and in reply to a famous Musk fanboy, if not actually the “alt” of the richest person in the world. So it’s fair to ask: Where does Smith end and Musk’s ecosystem begin?

That’s a question drawing attention from neuro-ethicists, who say Smith’s case highlights key issues about the prospect that brain implants and AI will one day merge.

What’s amazing, of course, is that Smith can steer a pointer with his brain well enough to text with his wife at home and answer our emails. Since he’d only been semi-famous for a few days, he told us, he didn’t want to opine too much on philosophical questions about the authenticity of his AI-assisted posts. “I don’t want to wade in over my head,” he said. “I leave it for experts to argue about that!”

The eye tracker Smith previously used to type required low light and worked only indoors. “I was basically Batman stuck in a dark room,” he explained in a video he posted to X. The implant lets him type in brighter spaces—even outdoors—and quite a bit faster.

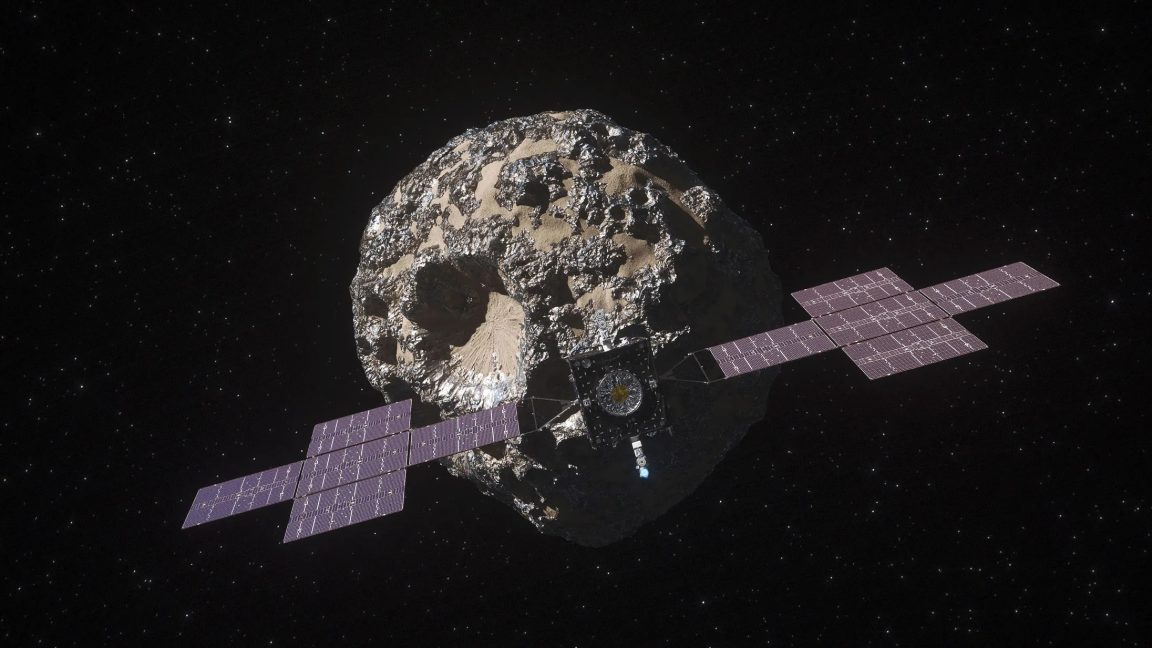

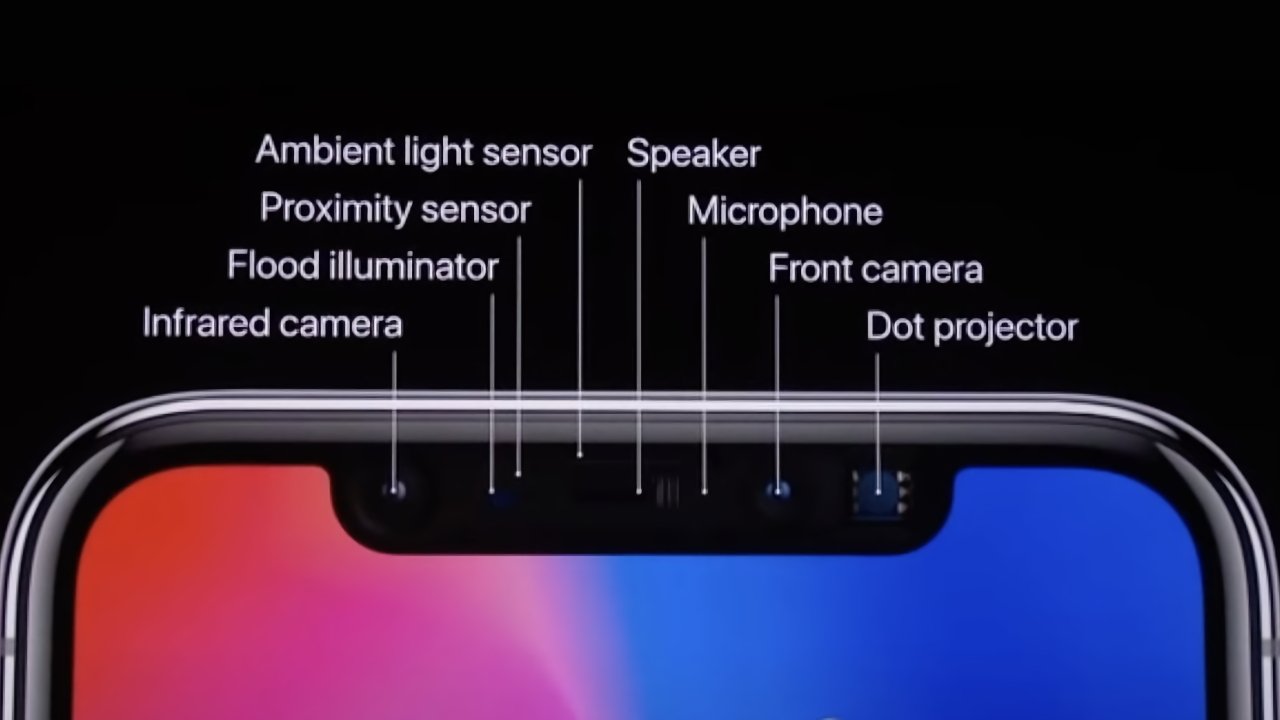

The thin wires implanted in his brain listen to neurons. Because their signals are faint, they need to be amplified, filtered, and sampled to extract the most important features—which are sent from his brain to a MacBook via radio and then processed further to let him move the computer pointer.

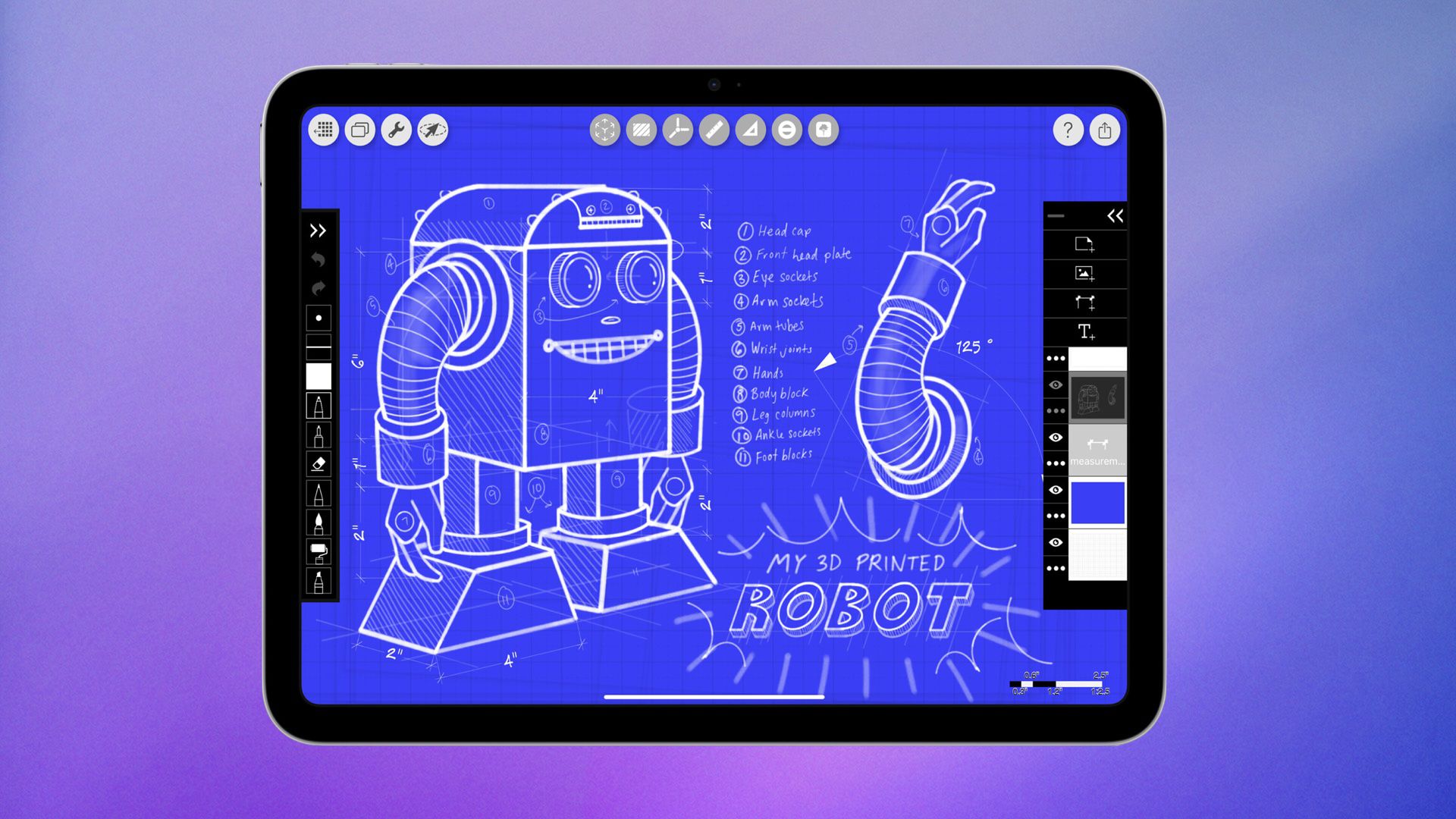

With control over this pointer, Smith types using an app. But various AI technologies are helping him express himself more naturally and quickly. One is a service from a startup called ElevenLabs, which created a copy of his voice from some recordings he’d made when he was healthy. The “voice clone” can read his written words aloud in a way that sounds like him. (The service is already used by other ALS patients who don’t have implants.)

Researchers have been studying how ALS patients feel about the idea of aids like language assistants. In 2022, Klein interviewed 51 people with ALS and found a range of different opinions.

Some people are exacting, like a librarian who felt everything she communicated had to be her words. Others are easygoing—an entertainer felt it would be more important to keep up with a fast-moving conversation.

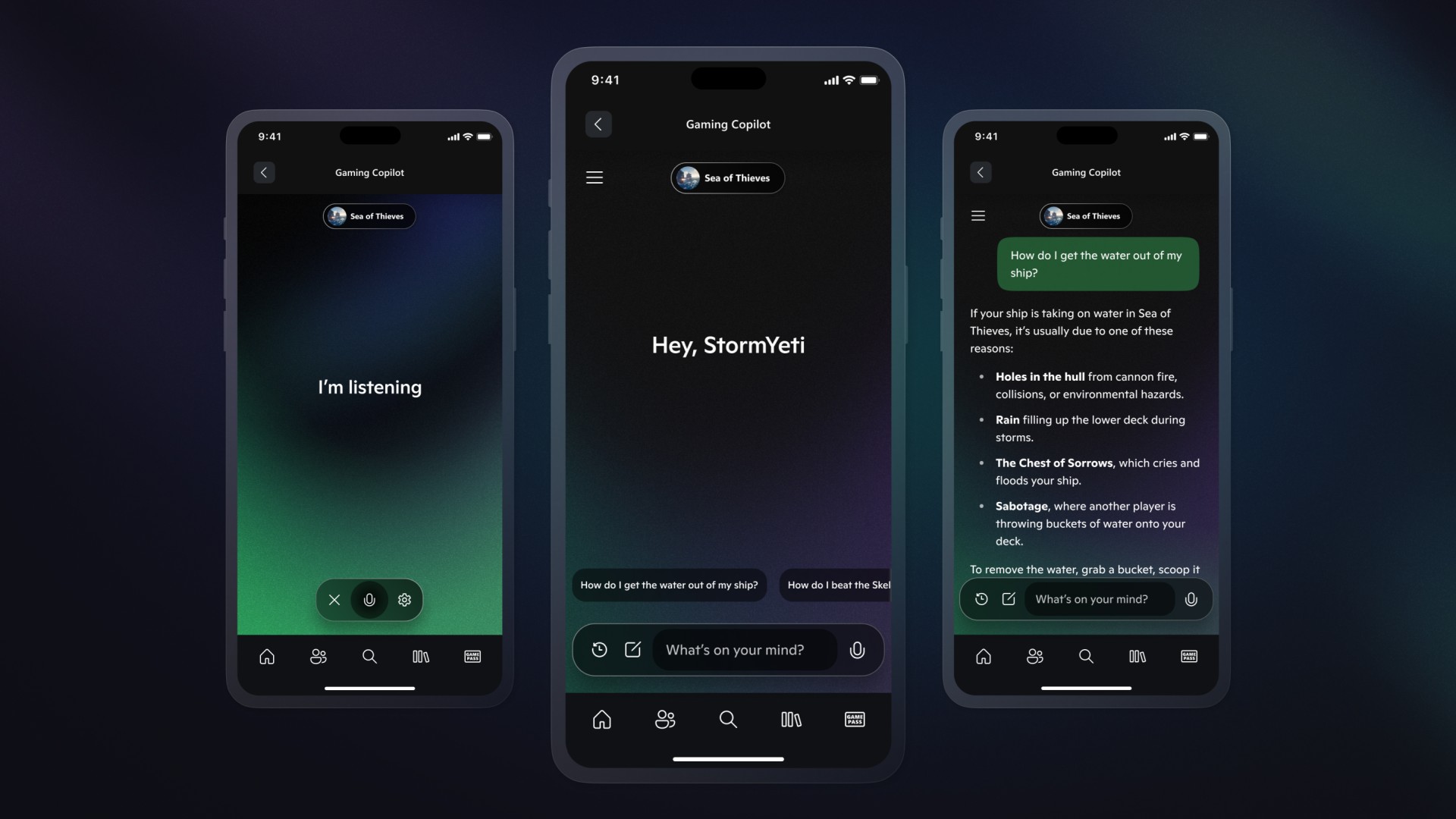

In the video Smith posted online, he said Neuralink engineers had started using language models including ChatGPT and Grok to serve up a selection of relevant replies to questions, as well as options for things he could say in conversations going on around him. One example that he outlined: “My friend asked me for ideas for his girlfriend who loves horses. I chose the option that told him in my voice to get her a bouquet of carrots. What a creative and funny idea.”

These aren’t really his thoughts, but they will do—since brain-clicking once in a menu of choices is much faster than typing out a complete answer, which can take minutes.

Smith told us he wants to take things a step further. He says he has an idea for a more “personal” large language model that “trains on my past writing and answers with my opinions and style.” He told MIT Technology Review that he’s looking for someone willing to create it for him: “If you know of anyone who wants to help me, let me know.”

![[The AI Show Episode 154]: AI Answers: The Future of AI Agents at Work, Building an AI Roadmap, Choosing the Right Tools, & Responsible AI Use](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20154%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 153]: OpenAI Releases o3-Pro, Disney Sues Midjourney, Altman: “Gentle Singularity” Is Here, AI and Jobs & News Sites Getting Crushed by AI Search](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20153%20cover.png)

![GrandChase tier list of the best characters available [June 2025]](https://media.pocketgamer.com/artwork/na-33057-1637756796/grandchase-ios-android-3rd-anniversary.jpg?#)

.jpg?#)

_marcos_alvarado_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Apple in Last-Minute Talks to Avoid More EU Fines Over App Store Rules [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97680/97680/97680-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds tvOS 26 Beta 2 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97691/97691/97691-640.jpg)