Your gut microbes might encourage criminal behavior

A few years ago, a Belgian man in his 30s drove into a lamppost. Twice. Local authorities found that his blood alcohol level was four times the legal limit. Over the space of a few years, the man was apprehended for drunk driving three times. And on all three occasions, he insisted he hadn’t been…

A few years ago, a Belgian man in his 30s drove into a lamppost. Twice. Local authorities found that his blood alcohol level was four times the legal limit. Over the space of a few years, the man was apprehended for drunk driving three times. And on all three occasions, he insisted he hadn’t been drinking.

He was telling the truth. A doctor later diagnosed auto-brewery syndrome—a rare condition in which the body makes its own alcohol. Microbes living inside the man’s body were fermenting the carbohydrates in his diet to create ethanol. Last year, he was acquitted of drunk driving.

His case, along with several other scientific studies, raises a fascinating question for microbiology, neuroscience, and the law: How much of our behavior can we blame on our microbes?

Each of us hosts vast communities of tiny bacteria, archaea (which are a bit like bacteria), fungi, and even viruses all over our bodies. The largest collection resides in our guts, which play home to trillions of them. You have more microbial cells than human cells in your body. In some ways, we’re more microbe than human.

Microbiologists are still getting to grips with what all these microbes do. Some seem to help us break down food. Others produce chemicals that are important for our health in some way. But the picture is extremely complicated, partly because of the myriad ways microbes can interact with each other.

But they also interact with the human nervous system. Microbes can produce compounds that affect the way neurons work. They also influence the functioning of the immune system, which can have knock-on effects on the brain. And they seem to be able to communicate with the brain via the vagus nerve.

If microbes can influence our brains, could they also explain some of our behavior, including the criminal sort? Some microbiologists think so, at least in theory. “Microbes control us more than we think they do,” says Emma Allen-Vercoe, a microbiologist at the University of Guelph in Canada.

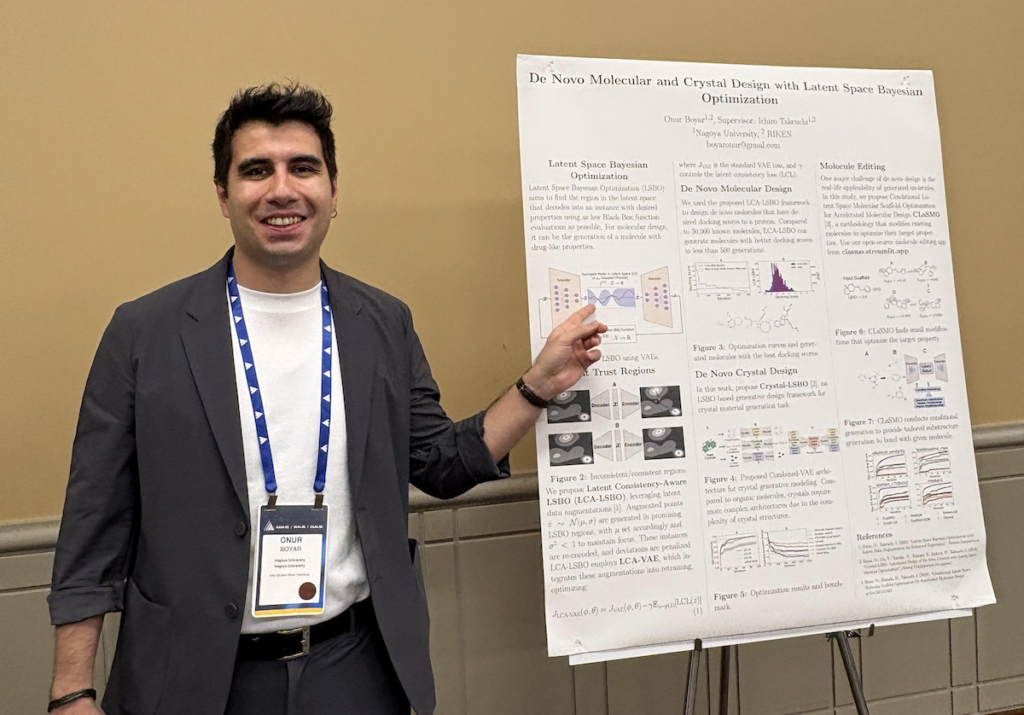

Researchers have come up with a name for applications of microbiology to criminal law: the legalome. A better understanding of how microbes influence our behavior could not only affect legal proceedings but also shape crime prevention and rehabilitation efforts, argue Susan Prescott, a pediatrician and immunologist at the University of Western Australia, and her colleagues.

“For the person unaware that they have auto-brewery syndrome, we can argue that microbes are like a marionettist pulling the strings in what would otherwise be labeled as criminal behavior,” says Prescott.

Auto-brewery syndrome is a fairly straightforward example (it has been involved in the acquittal of at least two people so far), but other brain-microbe relationships are likely to be more complicated. We do know a little about one microbe that seems to influence behavior: Toxoplasmosis gondii, a parasite that reproduces in cats and spreads to other animals via cat feces.

The parasite is best known for changing the behavior of rodents in ways that make them easier prey—an infection seems to make mice permanently lose their fear of cats. Research in humans is nowhere near conclusive, but some studies have linked infections with the parasite to personality changes, increased aggression, and impulsivity.

“That’s an example of microbiology that we know affects the brain and could potentially affect the legal standpoint of someone who’s being tried for a crime,” says Allen-Vercoe. “They might say ‘My microbes made me do it,’ and I might believe them.”

There’s more evidence linking gut microbes to behavior in mice, which are some of the most well-studied creatures. One study involved fecal transplants—a procedure that involves inserting fecal matter from one animal into the intestines of another. Because feces contain so much gut bacteria, fecal transplants can go some way to swap out a gut microbiome. (Humans are doing this too—and it seems to be a remarkably effective way to treat persistent C. difficile infections in people.)

Back in 2013, scientists at McMaster University in Canada performed fecal transplants between two strains of mice, one that is known for being timid and another that tends to be rather gregarious. This swapping of gut microbes also seemed to swap their behavior—the timid mice became more gregarious, and vice versa.

Microbiologists have since held up this study as one of the clearest demonstrations of how changing gut microbes can change behavior—at least in mice. “But the question is: How much do they control you, and how much is the human part of you able to overcome that control?” says Allen-Vercoe. “And that’s a really tough question to answer.”

After all, our gut microbiomes, though relatively stable, can change. Your diet, exercise routine, environment, and even the people you live with can shape the communities of microbes that live on and in you. And the ways these communities shift and influence behavior might be slightly different for everyone. Pinning down precise links between certain microbes and criminal behaviors will be extremely difficult, if not impossible.

“I don’t think you’re going to be able to take someone’s microbiome and say ‘Oh, look—you’ve got bug X, and that means you’re a serial killer,” says Allen-Vercoe.

Either way, Prescott hopes that advances in microbiology and metabolomics might help us better understand the links between microbes, the chemicals they produce, and criminal behaviors—and potentially even treat those behaviors.

“We could get to a place where microbial interventions are a part of therapeutic programming,” she says.

This article first appeared in The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, and read articles like this first, sign up here.

-Reviewer-Photo-SOURCE-Julian-Chokkattu-(no-border).jpg)

![[The AI Show Episode 146]: Rise of “AI-First” Companies, AI Job Disruption, GPT-4o Update Gets Rolled Back, How Big Consulting Firms Use AI, and Meta AI App](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20146%20cover.png)

![Life in Startup Pivot Hell with Ex-Microsoft Lonewolf Engineer Sam Crombie [Podcast #171]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1746753508177/0cd57f66-fdb0-4972-b285-1443a7db39fc.png?#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-Nintendo-Switch-2-Hands-On-Preview-Mario-Kart-World-Impressions-&-More!-00-10-30.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Andrey_Khokhlov_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![New iPad 11 (A16) On Sale for Just $277.78! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97273/97273/97273-640.jpg)

![Apple Foldable iPhone to Feature New Display Tech, 19% Thinner Panel [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97271/97271/97271-640.jpg)

![Apple Developing New Chips for Smart Glasses, Macs, AI Servers [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97269/97269/97269-640.jpg)

![[Weekly funding roundup May 3-9] VC inflow into Indian startups touches new high](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/WeeklyFundingRoundupNewLogo1-1739546168054.jpg)