What is "right" and what is "wrong"? — in IT

What is "right" and what is "wrong"? — in IT Originally written at pooyan.info Who is the author? Check out my profile on LinkedIn. Right and Wrong: Philosophical Debate The question of what is right and wrong has been a central theme of human thought for centuries. Is morality absolute, or does it depend on the context? Philosophers have long debated how ethical principles should be determined. Do we have "the good" and "the bad" or is it all relative? Let's begin with a general debate and see how the answer to the question evolved through history. Then, we will discuss how it applies to IT, our modern digital societies, and software development. Note: All the dates mentioned in this article are based on the Gregorian calendar. The Absolute Morality: Religious Thinking Religious teachings often promote the idea of absolute morality, where right and wrong are already known and defined set in the stone by divine commandments. For instance, in Christianity, the Ten Commandments serve as a guide for moral behavior, while in Islam, the Quran provides clear guidelines for what is considered righteous. These absolute frameworks suggest that morality is not subjective but dictated by a higher power. The God's commands are considered the "right" actions, and if you obey them, you will be rewarded for eternity. On the other hand, disobedient is considered "wrong," and you will be punished for eternity. Immanuel Kant (Emanuel Kant, 1724–1804, Germany), a German philosopher, echoed this sentiment with his theory of the categorical imperative, which asserts that moral actions are those that can be universally applied. As he famously said: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law." — Immanuel Kant Moral Relativism: The Collective Agreement In contrast, modern societies often adopt a relativistic view of morality, where right and wrong are determined collectively based on cultural, social, and situational factors. This perspective argues that morality is not fixed but evolves over time and across different societies. So, what is right? It depends! What is wrong? Again, it depends! Aboo Ali Sina (also known as Ebn-e Sina, or Avicenna in the West, 980–1037, Iran), an Iranian philosopher, physician, and the founder of modern medicine, believed in rational ethics. He thought morality should be grounded in intellect rather than dictated purely by external forces. He argued that the pursuit of knowledge and virtue leads to ethical behavior. " The highest good is that which is sought for its own sake, and the greatest evil is that which is avoided for its own sake. " — Aboo Ali Sina, The Book of Healing (Shafa) PS: Shafa means healing in Persian, coming from an Arabic word. Omar Khayyam (1048–1131, Iran), an Iranian philosopher, poet, and mathematician, known for his skeptical view of absolute truths, particularly in morality and existential questions. His poetry often reflected a deep understanding that what people consider "right" and "wrong" is ever-changing. In his poems, he was suggesting that "if something isn’t working, why not break it down and redesign it based on a deeper understanding of needs?" He suggests there is no definitive answers, because it depends on context. This is an example of one of his poems, in which he challenges the religious idea of absolute morality coming from a higher power: And this is the "translation" of it: " They say there will be paradise and houris divine, With rivers of wine, honey, and things so fine. If we choose wine and love in this life, why regret? Since in the end, that’s what we’re promised to get! " — Omar Khayyam, Robaiyat #87 (translation) Remember, words in Farsi have many different meanings, and no translation can capture the different layers of magic and the depth of the original text! Molla Sadra (1571–1640, Iran), an Iranian philosopher, also challenged the idea of absolute morality. In his Substantial Motion theory, he argued that everything is in a constant state of change—including morality, knowledge, and understanding. He suggests that there is no absolute "right" or "wrong," only different intensities of truth based on context. "Being is a single reality that appears in different degrees and intensities." — Molla Sadra, Asfar ol-Arba‘a (The Four Journeys of the Intellect) He also said: "The essence of things is not fixed; rather, it transforms in response to time, space, and perception." — Molla Sadra Sartre (Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre, 1905–1980, France), a French philosopher, championed the idea of existentialism, asserting that individuals are free to define their own values and morality. Sartre wrote: "Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself." — Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism This notion of freedom and choice highlights the subjective nature of morality in a

What is "right" and what is "wrong"? — in IT

Originally written at pooyan.info

Who is the author? Check out my profile on LinkedIn.

Right and Wrong: Philosophical Debate

The question of what is right and wrong has been a central theme of human thought for centuries. Is morality absolute, or does it depend on the context? Philosophers have long debated how ethical principles should be determined. Do we have "the good" and "the bad" or is it all relative?

Let's begin with a general debate and see how the answer to the question evolved through history. Then, we will discuss how it applies to IT, our modern digital societies, and software development.

Note: All the dates mentioned in this article are based on the Gregorian calendar.

The Absolute Morality: Religious Thinking

Religious teachings often promote the idea of absolute morality, where right and wrong are already known and defined set in the stone by divine commandments. For instance, in Christianity, the Ten Commandments serve as a guide for moral behavior, while in Islam, the Quran provides clear guidelines for what is considered righteous. These absolute frameworks suggest that morality is not subjective but dictated by a higher power. The God's commands are considered the "right" actions, and if you obey them, you will be rewarded for eternity. On the other hand, disobedient is considered "wrong," and you will be punished for eternity.

Immanuel Kant (Emanuel Kant, 1724–1804, Germany), a German philosopher, echoed this sentiment with his theory of the categorical imperative, which asserts that moral actions are those that can be universally applied. As he famously said:

"Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law." — Immanuel Kant

Moral Relativism: The Collective Agreement

In contrast, modern societies often adopt a relativistic view of morality, where right and wrong are determined collectively based on cultural, social, and situational factors. This perspective argues that morality is not fixed but evolves over time and across different societies.

So, what is right? It depends!

What is wrong? Again, it depends!

Aboo Ali Sina (also known as Ebn-e Sina, or Avicenna in the West, 980–1037, Iran), an Iranian philosopher, physician, and the founder of modern medicine, believed in rational ethics. He thought morality should be grounded in intellect rather than dictated purely by external forces. He argued that the pursuit of knowledge and virtue leads to ethical behavior.

" The highest good is that which is sought for its own sake, and the greatest evil is that which is avoided for its own sake. " — Aboo Ali Sina, The Book of Healing (Shafa)

PS: Shafa means healing in Persian, coming from an Arabic word.

Omar Khayyam (1048–1131, Iran), an Iranian philosopher, poet, and mathematician, known for his skeptical view of absolute truths, particularly in morality and existential questions. His poetry often reflected a deep understanding that what people consider "right" and "wrong" is ever-changing.

In his poems, he was suggesting that "if something isn’t working, why not break it down and redesign it based on a deeper understanding of needs?" He suggests there is no definitive answers, because it depends on context.

This is an example of one of his poems, in which he challenges the religious idea of absolute morality coming from a higher power:  And this is the "translation" of it:

And this is the "translation" of it:

" They say there will be paradise and houris divine, With rivers of wine, honey, and things so fine. If we choose wine and love in this life, why regret? Since in the end, that’s what we’re promised to get! " — Omar Khayyam, Robaiyat #87 (translation)

Remember, words in Farsi have many different meanings, and no translation can capture the different layers of magic and the depth of the original text!

Molla Sadra (1571–1640, Iran), an Iranian philosopher, also challenged the idea of absolute morality. In his Substantial Motion theory, he argued that everything is in a constant state of change—including morality, knowledge, and understanding. He suggests that there is no absolute "right" or "wrong," only different intensities of truth based on context.

"Being is a single reality that appears in different degrees and intensities." — Molla Sadra, Asfar ol-Arba‘a (The Four Journeys of the Intellect)

He also said:

"The essence of things is not fixed; rather, it transforms in response to time, space, and perception." — Molla Sadra

Sartre (Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre, 1905–1980, France), a French philosopher, championed the idea of existentialism, asserting that individuals are free to define their own values and morality. Sartre wrote:

"Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself." — Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism

This notion of freedom and choice highlights the subjective nature of morality in a relativistic framework.

Traditional vs. Modern Thinking

This debate began earlier in the East, from Iran, and later a few centuries later, it was picked up in the West and evolved by philosophers like Kant and Sartre. Beyond Ebn-e Sina, Khayyam, Molla Sadra, Kant, and Sartre, many other thinkers have also contributed to this debate.

Persian thinkers throughout history have challenged the meaning of "good" and "bad" and the way we think about things. This used to be pretty common in Iranian/Persian culture during the pre-Arab invasion era, where in Mithra-ism and Zarathustra's teachings, people were encouraged to think and question things. Later, after the attack of Arabs/Islam, our ancestors created Shia Islam (the new religion of resistance) to kick out invaders. Philosophers used the old Persian teachings to encourage the society to think again and push back the new strict Sunni/Arab/invader/colonist mindset who wanted to enslave the world.

That's why a few centuries after that, Aboo Ali Sina, Omar Khayyam, and Molla Sadra argued that "the answers" are not fixed but evolves over time and context. They promoted the idea that decisions should be made with adaptability in mind.

A few centuries later, Friedrich Nietzsche critiqued the traditional Western moral systems, declaring, "God is dead" (this has nothing to do against religion and beliefs in my opinion and is more about ways of thinking), and then he suggested that humanity must create its own values (focusing on thinking rather than just following).

On the other hand, Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948, India) emphasized universal principles of truth and nonviolence, saying, "You may never know what results come of your actions, but if you do nothing, there will be no result."

These contrasting views highlight the complexity of defining right and wrong, revealing that morality often depends on the interplay of culture, context, and individual beliefs.

Okay, but I work in IT. What does this have to do with me?

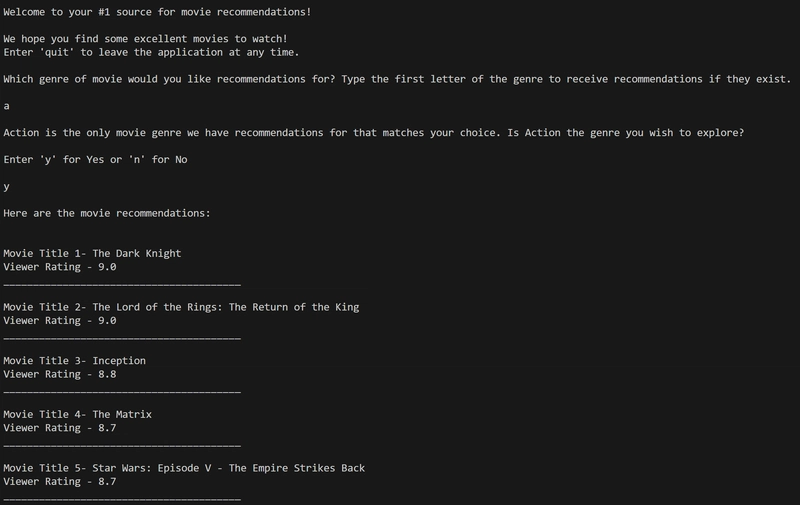

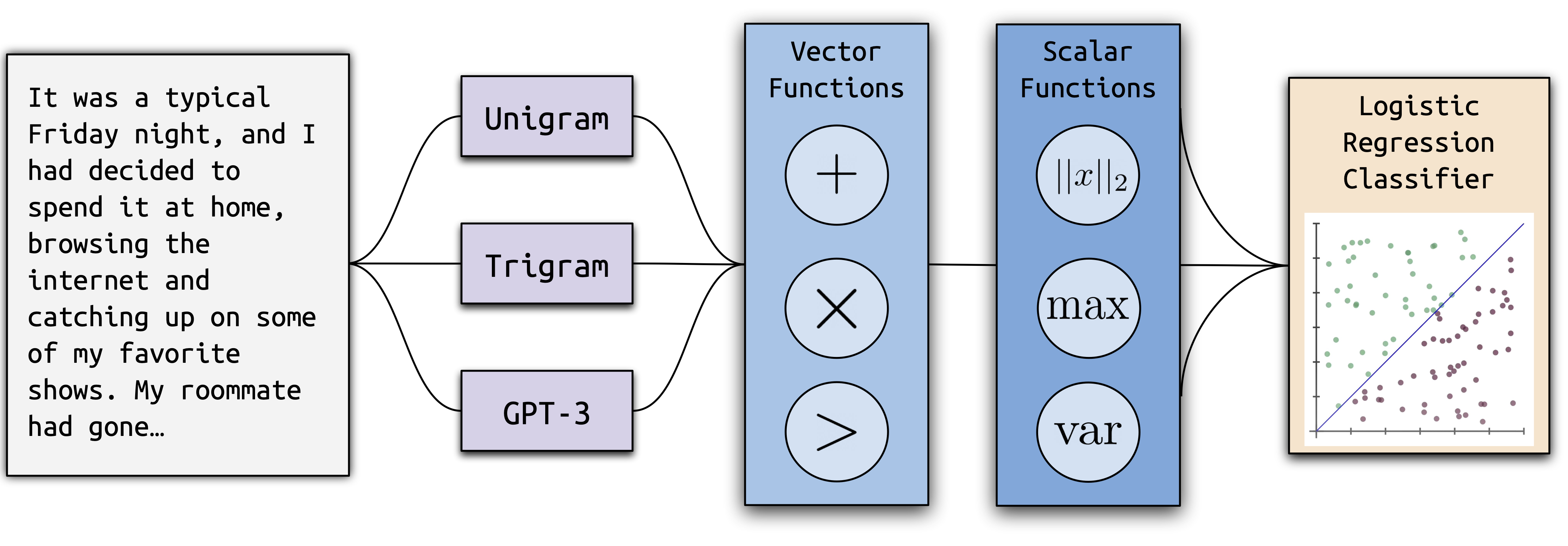

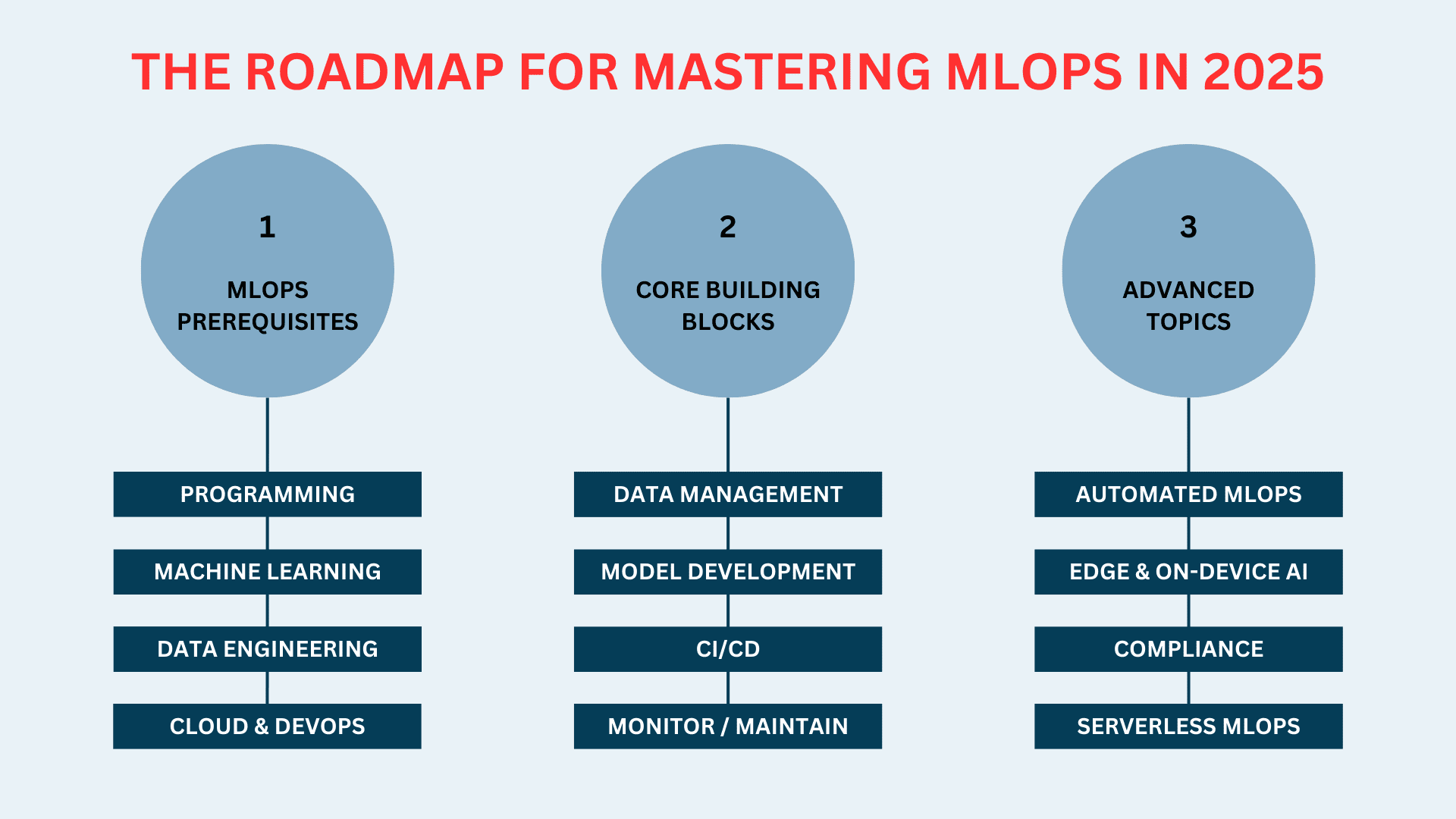

In the world of IT, infrastructure, operations, and programming, the debate between absolutes and contextual decision-making is highly relevant. Unlike morality, where traditional societies and many philosophers seeked to define a universal truth, around A superpower like "God" or "the mighty king" or religion, software development thrives on contextual decisions.

Some, still like the traditional absolute mindset and either blindly follow the hypes or just accept what a random person on the internet calls the "best practice" or "the tool that you should use"! The same applies to things like "the best solution architecture" or "the best programming language" ... That's why we always see conversations around "blah blah programming language is dead", "Golang is the best" or "Kubernetes is the answer to all infrastructure problems you can imagine"! — and you cannot even ask why?!

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

![Apple Watch to Get visionOS Inspired Refresh, Apple Intelligence Support [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96976/96976/96976-640.jpg)

![New Apple Watch Ad Features Real Emergency SOS Rescue [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96973/96973/96973-640.jpg)

![Apple Debuts Official Trailer for 'Murderbot' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96972/96972/96972-640.jpg)

![Alleged Case for Rumored iPhone 17 Pro Surfaces Online [Image]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96969/96969/96969-640.jpg)