The value of ‘almost.’ Why near misses can make or break you

Whether we like it or not, we live in a world that is ruthlessly optimized to reward results. Nonetheless, failure is a part of everyone’s life—and an essential part of achievement in fields ranging from sports to science. In fact, high achievers are those who fail more often—not less—than the average person. They take more risks, go outside their comfort zone, set more challenging goals, and engage more frequently and vigorously in improving their performance—and this is how they succeed. You can’t lose if you never play—you also can’t win. Runner-up But what about coming in second? Is there value to the “near miss”—to being so close to a win, but falling short? In education, being salutatorian is impressive. But it still means you miss out on the valedictory speech and its attendant scholarship. A high spot on the university waitig list rarely becomes an enrollment offer. In careers, the runner-up performer might earn a congratulatory email but not the promotion or hefty salary increase; the second-best job interview candidate gets little consolation from knowing they almost received a job offer but are still unemployed. Salespeople who hit 99% of their quota still forfeit the Hawaiian-vacation incentive and bonus. In research, the lab that publishes second loses the patent, the grant, and the headlines. And if you are the runner-up in a presidential election, there’s at best a slim chance you can run again in the future, and your popularity may actually decrease after losing (in politics, this loser effect leads to a dip in confidence from voters, and there’s often no time for a second chance). Near misses as opportunity And yet, near misses are not as disastrous as the above thought experiments suggest. Indeed, finishing a hair’s breadth behind the winner still means you’ve outperformed almost everyone else—be they hundreds of classmates, thousands of job applicants, or an entire electorate. Moreover, the person who edges you out isn’t necessarily better on merit alone—factors like political currents, privilege, or just plain luck can tip the scales. Perhaps most importantly, coming up just short can serve as a springboard for growth, offering the chance to learn, adapt, and come back stronger—provided you choose to seize it. Here’s why: Lessons learned First, while everyone prefers success to failure, it is often easier to learn from failure than from success. Success tells you that you are great; it is the socially accepted way to provide you with positive feedback on your talents, reinforcing your self-belief, and inflating your ego. While this sounds great—and without much in the way of downside—success is also likely to generate complacency, overconfidence, and arrogance (it’s much easier to stay humble in defeat). Conversely, failures are opportunities to learn, especially when you see them as learning experiments that provide you with critical feedback on your skills, choices, and behaviors. As Niels Bohr wisely noted, “An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.” In short, a near miss can act as an inherently, if brutally honest audit of your assumptions and strategies—uncovering blind spots that success tends to conceal. By forcing you—or at least inviting you—to diagnose exactly why you fell short, a near miss suggests you refine your mental models; rethink and tweak your tactics; and build new, better tested, decision-making muscles. Failing enthusiastically Second, failure increases the gap between your aspirational self (who you want to be) and your actual self (who you are, at least from a reputational standpoint). This uncomfortable psychological gap is only reduced through hard work, grit, and persistence, which together strengthen your chances of succeeding in the future. At the very least, they help you become a better version of yourself, even if you don’t succeed in achieving a sought-after prize or goal. As Winston Churchill famously noted, “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.” Importantly, near misses can be a powerful form of failure precisely because they hurt the most. Being so close to a success can reaffirm your determination and reignite your ambition. Every extraordinary achiever (across fields) differs from others in one important way: they are less likely to be satisfied with their achievements. Indeed, the most common reason people fail to learn from failure is that they are too wounded or hurt by their lack of success, to the point that it extinguishes their drive. In contrast, extraordinary achievers will not give up or let go—even when their failures are hard to digest. This ambitious mindset helps them seek to understand the factors leading to their near misses without getting deflated or depressed by them. Instead, it makes them even hungrier for victory, resilient, and focused on bouncing back stronger. Emotionally resilient Thir

Whether we like it or not, we live in a world that is ruthlessly optimized to reward results. Nonetheless, failure is a part of everyone’s life—and an essential part of achievement in fields ranging from sports to science.

In fact, high achievers are those who fail more often—not less—than the average person. They take more risks, go outside their comfort zone, set more challenging goals, and engage more frequently and vigorously in improving their performance—and this is how they succeed. You can’t lose if you never play—you also can’t win.

Runner-up

But what about coming in second? Is there value to the “near miss”—to being so close to a win, but falling short?

In education, being salutatorian is impressive. But it still means you miss out on the valedictory speech and its attendant scholarship. A high spot on the university waitig list rarely becomes an enrollment offer. In careers, the runner-up performer might earn a congratulatory email but not the promotion or hefty salary increase; the second-best job interview candidate gets little consolation from knowing they almost received a job offer but are still unemployed.

Salespeople who hit 99% of their quota still forfeit the Hawaiian-vacation incentive and bonus. In research, the lab that publishes second loses the patent, the grant, and the headlines. And if you are the runner-up in a presidential election, there’s at best a slim chance you can run again in the future, and your popularity may actually decrease after losing (in politics, this loser effect leads to a dip in confidence from voters, and there’s often no time for a second chance).

Near misses as opportunity

And yet, near misses are not as disastrous as the above thought experiments suggest.

Indeed, finishing a hair’s breadth behind the winner still means you’ve outperformed almost everyone else—be they hundreds of classmates, thousands of job applicants, or an entire electorate. Moreover, the person who edges you out isn’t necessarily better on merit alone—factors like political currents, privilege, or just plain luck can tip the scales.

Perhaps most importantly, coming up just short can serve as a springboard for growth, offering the chance to learn, adapt, and come back stronger—provided you choose to seize it. Here’s why:

Lessons learned

First, while everyone prefers success to failure, it is often easier to learn from failure than from success. Success tells you that you are great; it is the socially accepted way to provide you with positive feedback on your talents, reinforcing your self-belief, and inflating your ego. While this sounds great—and without much in the way of downside—success is also likely to generate complacency, overconfidence, and arrogance (it’s much easier to stay humble in defeat). Conversely, failures are opportunities to learn, especially when you see them as learning experiments that provide you with critical feedback on your skills, choices, and behaviors. As Niels Bohr wisely noted, “An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.”

In short, a near miss can act as an inherently, if brutally honest audit of your assumptions and strategies—uncovering blind spots that success tends to conceal. By forcing you—or at least inviting you—to diagnose exactly why you fell short, a near miss suggests you refine your mental models; rethink and tweak your tactics; and build new, better tested, decision-making muscles.

Failing enthusiastically

Second, failure increases the gap between your aspirational self (who you want to be) and your actual self (who you are, at least from a reputational standpoint). This uncomfortable psychological gap is only reduced through hard work, grit, and persistence, which together strengthen your chances of succeeding in the future. At the very least, they help you become a better version of yourself, even if you don’t succeed in achieving a sought-after prize or goal. As Winston Churchill famously noted, “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

Importantly, near misses can be a powerful form of failure precisely because they hurt the most. Being so close to a success can reaffirm your determination and reignite your ambition. Every extraordinary achiever (across fields) differs from others in one important way: they are less likely to be satisfied with their achievements. Indeed, the most common reason people fail to learn from failure is that they are too wounded or hurt by their lack of success, to the point that it extinguishes their drive. In contrast, extraordinary achievers will not give up or let go—even when their failures are hard to digest. This ambitious mindset helps them seek to understand the factors leading to their near misses without getting deflated or depressed by them. Instead, it makes them even hungrier for victory, resilient, and focused on bouncing back stronger.

Emotionally resilient

Third, the way you respond to any form of defeat or failure, and especially the painful near misses, sends a powerful signal to everyone around you—investors, bosses, or teammates—that you’re emotionally mature, resilient, and coachable. Humans have a general tendency to attribute their successes to their own talents and merit, while blaming others, or situations, for their failures and misses. Avoiding this tendency makes you an exception to the norm. This will be noticed and will impress others. While resilience is largely a function of your personality (the more emotionally stable, extroverted, curious, agreeable, and especially conscientious you are, the more resilience you will show), we can all work to increase our resilience if we truly care about achieving our end goal, by becoming grittier and harnessing whatever mental toughness we have.

When you dissect a near miss with curiosity and humility, you demonstrate a growth mindset that invites collaboration and sparks confidence in your potential. Visible resilience often earns more credibility (and resources) than a flawless run, because it shows you’re willing to learn in public. Over time, people who witness your thoughtful rebound become your strongest advocates, eager to back the next iteration of your vision. Life, despite how it feels in disappointing moments, is not a final exam but a continuous assessment; what matters most is not brilliant one-off successes but reliable, steady, determined excellence. As Aristotle pointed out, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

Greater legacies

To be sure, there’s no shortage of prominent historical figures who confirm how near misses and other kinds of failures in their early career stages were poor indicators of their actual talent and potential but instead unfortunate or unlucky episodes, uncharacteristic of their brilliance. Consider Roger Federer: after six runner-up finishes on tour, he finally lifted Wimbledon’s trophy in 2003 and would go on to amass 20 Grand Slam titles. The Netherlands of 1974, whose Total Football lost the final, rewrote soccer’s playbook. J.K. Rowling, turned down by 12 publishers, went on to sell over 600 million Harry Potter copies. Barbara McClintock, whose “jumping genes” work was ignored for decades, earned a 1983 Nobel Prize for the discovery. Meryl Streep, whose first Oscar nod in 1979 went unrewarded, has since racked up 21 nominations and 3 wins. The Beatles were rejected by Decca as “yesterday’s sound” before selling some 1.6 billion records. And Alibaba, once dwarfed by eBay in China, now serves over a billion annual active consumers. Each of these (and many other) examples provide evidence that near misses can herald even greater legacies.

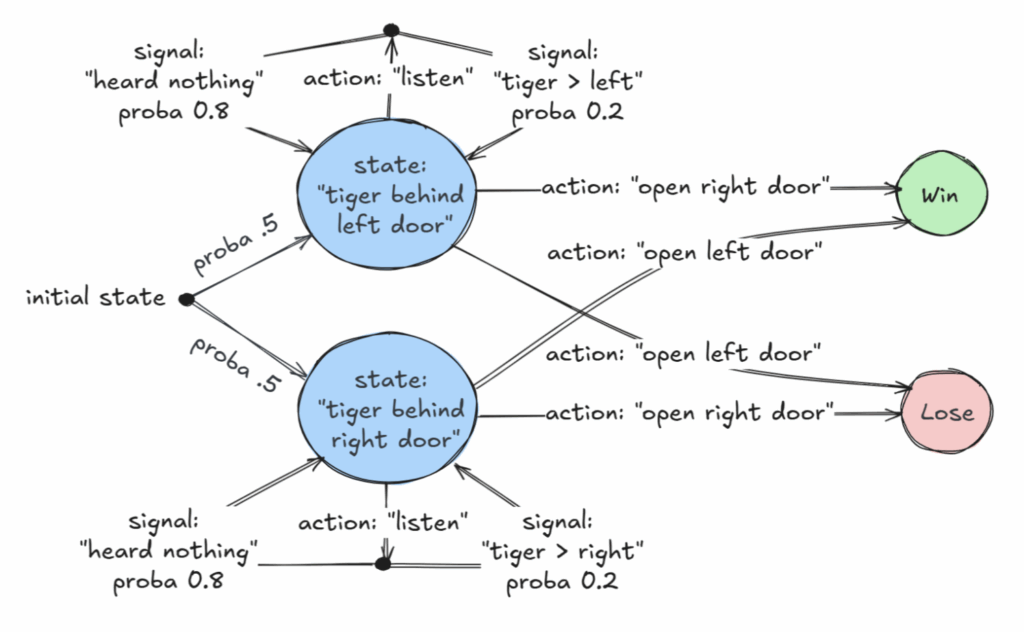

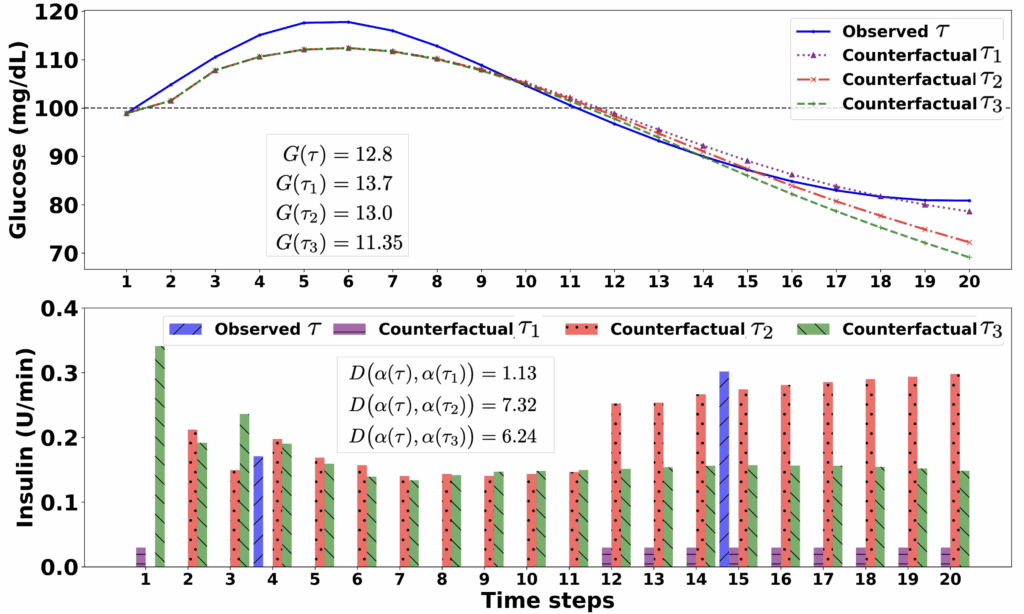

Ultimately, the sting of “almost” is less a verdict on your potential than an invitation to hone it. Near misses aren’t life sentences—they’re signposts pointing to gaps in your strategy, fuel for your ambition, and a live demonstration of your character to the world. While it is tempting to ruminate about what could have or should have happened, the truth is we never know. We all indulge in counterfactual fantasies—those “what if” spirals where we picture an alternate universe in which we married someone else, took the other job, or moved to that city. Psychologists call them sliding doors moments: innocuous-seeming forks in the road that, in hindsight, feel like cosmic turning points. But while it’s human to ruminate, it’s wiser to remember that we’re not omniscient authors of our own lives. The illusion of total control is just that—an illusion.

More often than not, the best way to recover from regret or disappointment is not by obsessing over the road not taken, but by taking a different road. Que será, será. Life is less about scripting your destiny than adapting to its plot twists. In other words, how you react to failure matters, but failure is too brutal and negative a word for simply not getting what you think you preferred or wanted, especially when it may not even be what you actually needed or ought to have preferred. When we embrace each narrow defeat as data, not destiny, we are able to build the very habits and resilience that turn “almost” into subsequent undeniable success. As the saying goes, experience is what you get when you didn’t get what you wanted. We add that experience can be more valuable than the objective success of getting what you wanted. In fact, enjoyment of objectives successes including of awards and victories, tends to be more short-lived than we expect.

We need not define ourselves by our past and present achievements. Who we are also comprises our future self, including our possible selves—the parts of our character and identity that are actually the only ones we can influence.

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

.jpg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Vladimir_Stanisic_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Design_Pics_Inc_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Latest Galaxy Z Fold 7 leak leaves very little to the imagination [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/galaxy-z-fold-7-teaser-1.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Mercedes, Audi, Volvo Reject Apple's New CarPlay Ultra [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97711/97711/97711-640.jpg)

![Apple Considers LX Semicon and LG Innotek Components for iPad OLED Displays [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97699/97699/97699-640.jpg)