Houston is sinking half an inch per year—and it’s not alone

In Texas, parts of Houston are sinking at a rate faster than 10 millimeters—or about two-fifths of an inch—per year. Parts of Dallas and Fort Worth are sinking more than 5 millimeters per year. While that may sound small, it adds up: Every few millimeters that a city sinks can cause cracks in roads or tilt building foundations, and make that region more vulnerable to extreme flooding. And those Texas cities aren’t alone: Twenty-five other major cities—from New York and San Francisco to Boston and Oklahoma City—are also sinking, according to a new study, putting more than 34 million people at risk. Cities can sink for a few reasons. Buildings are heavy, and so sometimes the ground below them can settle and constrict, especially if they’re built on top of sand. Erosion or natural land and tectonic movements can come into play, too. But the most common cause for cities sinking lower and lower—a process known as subsidence—is groundwater extraction. Across the county, half of the U.S. population relies on groundwater for drinking, irrigation, or industrial uses. When cities pump that water from the ground below, the land then compacts and settles down, bringing the city, and the structural integrity of its buildings roads, and bridges, with it. “Land subsidence is often invisible—until it isn’t,” says Manoochehr Shirzaei, a geophysicist at Virginia Tech and coauthor of the study, published today in the journal Nature Cities. “It undermines building foundations, damages roads and pipelines, and compromises flood defenses. . . . It’s a quiet hazard, but its effects accumulate, potentially amplifying damage during storms or earthquakes.” All 28 major U.S. cities are shrinking For their study, Shirzaei and his team focused on the 28 most populous U.S. cities, which cover nearly 12% of the country’s population. Previous studies about subsidence often focused just on coastal regions or individual cities, ignoring the widespread urban risk. Researchers used satellite-based radar measurements to create high-resolution maps of those cities’ sinking land. The researchers expected to see subsidence in places like Houston and New Orleans. Houston has long been one of the fastest-sinking cities because of groundwater mining and oil and gas extraction; and New Orleans is built on top of soft, marshy land, with a drainage system that runs through the city. But they found subsidence in all 28 cities they examined—including Chicago, Columbus, Seattle, and Denver. “The widespread nature of the hazard was striking,” Shirzaei says. In 25 out of the 28 cities, at least 65% of the urban area is sinking. In some cities, that’s even greater: Chicago, Dallas, Columbus, Detroit, Fort Worth, Denver, New York, Indianapolis, Houston, and Charlotte saw the most widespread subsidence, with about 98% of their areas affected. Dallas, Fort Worth, and Houston saw the highest rates of subsidence, from about 5 millimeters to as much as 10 millimeters per year. Climate change, subsidence, and what cities can do Subsidence comes with a range of risks. In cities that are already prone to flooding, like New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., it can make floods even worse because more land is closer to sea level. That means when cities sink, they’re more vulnerable to climate change’s impacts. “Our study found that the cities with the highest rates of subsidence have also experienced numerous major flood events in the past two decades,” Shirzaei says. But at the same time, climate change can exacerbate subsidence, by increasing droughts and also the demand for groundwater. Cities still have time to act, Shirzaei says. They can slow this rate of sinking, or even reverse subsidence, by enacting regulations around groundwater use, managing aquifers better, and updating building codes to take soil movement into account. Cities should also adopt monitoring systems, integrate this risk into their urban planning, and retrofit any infrastructure that may be vulnerable. The key is that these responses must be tailored to a specific city—its ground makeup, its infrastructure, and its subsidence causes. “What works in San Diego won’t work in Memphis,” Shirzaei says.

In Texas, parts of Houston are sinking at a rate faster than 10 millimeters—or about two-fifths of an inch—per year. Parts of Dallas and Fort Worth are sinking more than 5 millimeters per year. While that may sound small, it adds up: Every few millimeters that a city sinks can cause cracks in roads or tilt building foundations, and make that region more vulnerable to extreme flooding.

And those Texas cities aren’t alone: Twenty-five other major cities—from New York and San Francisco to Boston and Oklahoma City—are also sinking, according to a new study, putting more than 34 million people at risk.

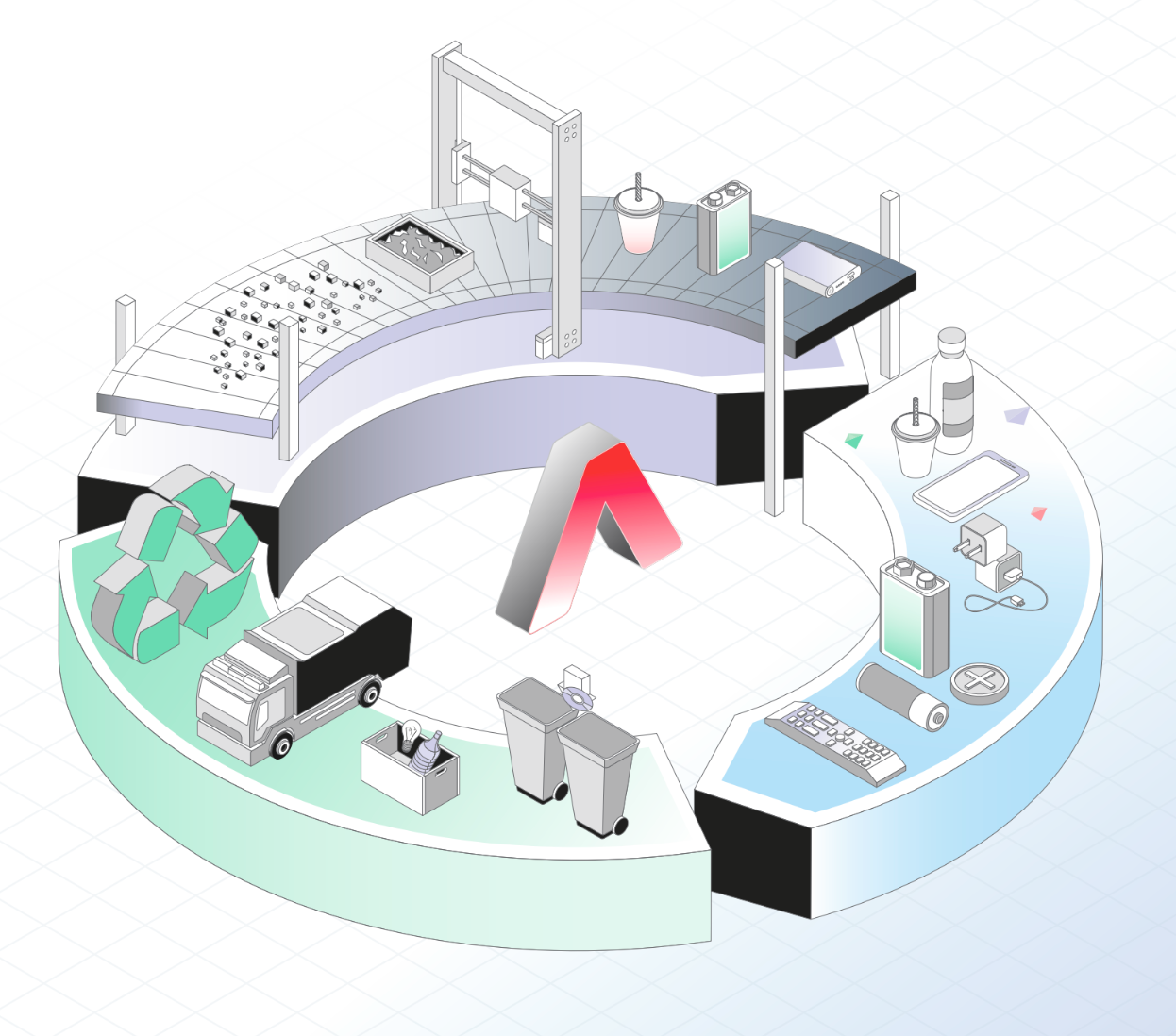

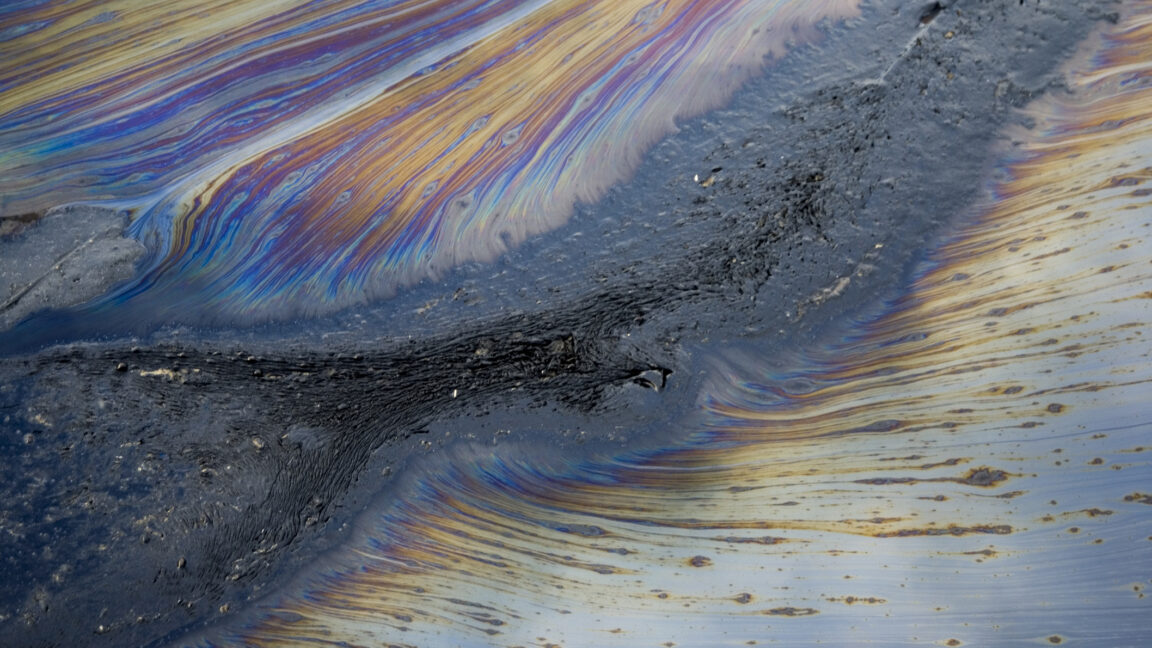

Cities can sink for a few reasons. Buildings are heavy, and so sometimes the ground below them can settle and constrict, especially if they’re built on top of sand. Erosion or natural land and tectonic movements can come into play, too. But the most common cause for cities sinking lower and lower—a process known as subsidence—is groundwater extraction.

Across the county, half of the U.S. population relies on groundwater for drinking, irrigation, or industrial uses. When cities pump that water from the ground below, the land then compacts and settles down, bringing the city, and the structural integrity of its buildings roads, and bridges, with it.

“Land subsidence is often invisible—until it isn’t,” says Manoochehr Shirzaei, a geophysicist at Virginia Tech and coauthor of the study, published today in the journal Nature Cities. “It undermines building foundations, damages roads and pipelines, and compromises flood defenses. . . . It’s a quiet hazard, but its effects accumulate, potentially amplifying damage during storms or earthquakes.”

All 28 major U.S. cities are shrinking

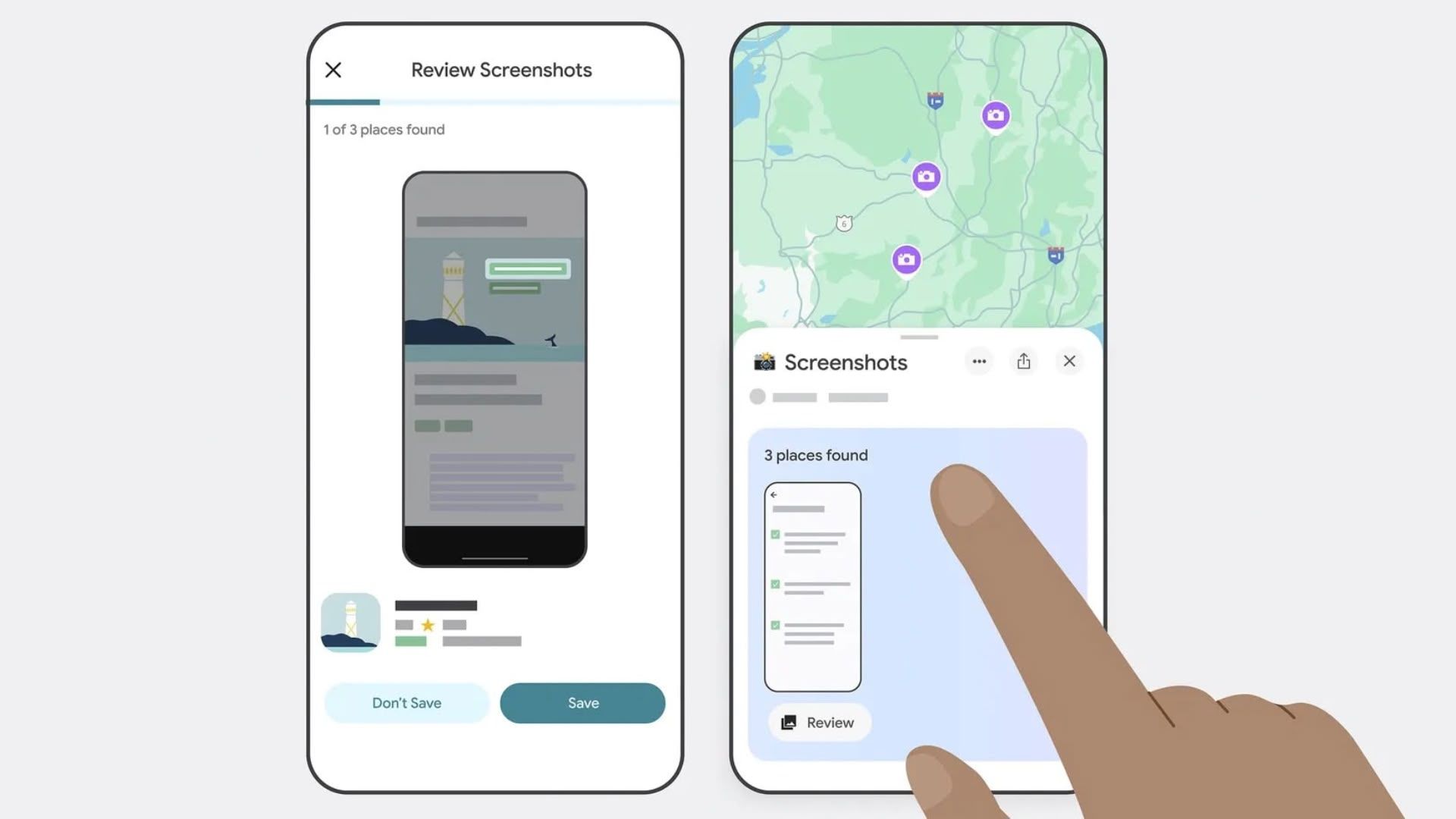

For their study, Shirzaei and his team focused on the 28 most populous U.S. cities, which cover nearly 12% of the country’s population. Previous studies about subsidence often focused just on coastal regions or individual cities, ignoring the widespread urban risk. Researchers used satellite-based radar measurements to create high-resolution maps of those cities’ sinking land.

The researchers expected to see subsidence in places like Houston and New Orleans. Houston has long been one of the fastest-sinking cities because of groundwater mining and oil and gas extraction; and New Orleans is built on top of soft, marshy land, with a drainage system that runs through the city. But they found subsidence in all 28 cities they examined—including Chicago, Columbus, Seattle, and Denver. “The widespread nature of the hazard was striking,” Shirzaei says.

In 25 out of the 28 cities, at least 65% of the urban area is sinking. In some cities, that’s even greater: Chicago, Dallas, Columbus, Detroit, Fort Worth, Denver, New York, Indianapolis, Houston, and Charlotte saw the most widespread subsidence, with about 98% of their areas affected. Dallas, Fort Worth, and Houston saw the highest rates of subsidence, from about 5 millimeters to as much as 10 millimeters per year.

Climate change, subsidence, and what cities can do

Subsidence comes with a range of risks. In cities that are already prone to flooding, like New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., it can make floods even worse because more land is closer to sea level.

That means when cities sink, they’re more vulnerable to climate change’s impacts. “Our study found that the cities with the highest rates of subsidence have also experienced numerous major flood events in the past two decades,” Shirzaei says. But at the same time, climate change can exacerbate subsidence, by increasing droughts and also the demand for groundwater.

Cities still have time to act, Shirzaei says. They can slow this rate of sinking, or even reverse subsidence, by enacting regulations around groundwater use, managing aquifers better, and updating building codes to take soil movement into account. Cities should also adopt monitoring systems, integrate this risk into their urban planning, and retrofit any infrastructure that may be vulnerable.

The key is that these responses must be tailored to a specific city—its ground makeup, its infrastructure, and its subsidence causes. “What works in San Diego won’t work in Memphis,” Shirzaei says.

![[The AI Show Episode 146]: Rise of “AI-First” Companies, AI Job Disruption, GPT-4o Update Gets Rolled Back, How Big Consulting Firms Use AI, and Meta AI App](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20146%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The Premium Python Programming PCEP Certification Prep Bundle (67% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Honor 400 series officially launching on May 22 as design is revealed [Video]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/05/honor-400-series-announcement-1.png?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Beats Studio Pro Wireless Headphones Now Just $169.95 - Save 51%! [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97258/97258/97258-640.jpg)