Endless growth, endless harm: Facebook is a symptom, not an outlier

The recent exposé Careless People, by former Facebook (now Meta) executive Sarah Wynn-Williams, has received significant attention for its jaw-dropping revelations about the social media company and its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg. According to the author, company decisions enabled the Chinese Communist Party to suppress dissent, undermined the mental health of teenage girls, and led to genocide in Myanmar and election interference in the U.S. While there has been much attention to details showing the moral bankruptcy of Zuckerberg and former COO Sheryl Sandberg, there has been less discussion of how financial pressures shaped executives’ decisions. Are Meta’s leaders just “bad apples,” or are the many troubling revelations in Careless People representative of pervasive problems across corporate America? While Careless People focuses on Facebook, it also prompts a broader reflection on the tech industry as a whole. Companies like Amazon, X, Google, YouTube, TikTok, and many others similarly operate extractive growth models that prioritize engagement, surveillance, and monetization over social responsibility. What Wynn-Williams has laid bare is a shared playbook of scale over ethics. Facebook’s meteoric rise—and the ethical corners cut by its leaders to meet its goals—reveals fatal flaws at the heart of growth-obsessed capitalism. The company had a vast infrastructure overseen by a chief growth officer operating “. . . fast and loose, and always looking for opportunities in the gray area created by the lack of regulation.” When Facebook reached 1 billion users, COO Javier Olivan (who succeeded Sandberg) expressed fear and uncertainty, not pride and accomplishment, because it meant the company had to figure out things “like how to reach children, how to get into places like China that are hostile to any social media site.” The company engineered algorithms to maximize time spent on the platform—regardless of whether that meant radicalizing users, fostering election misinformation, or taking advantage of people’s vulnerability. Even when Facebook became a trillion-dollar company, internal discussions continued to emphasize seizing vulnerable markets (like teenagers experiencing mental health crises) because these were deemed “high-value” audiences. In internal documents, Facebook acknowledged that its platforms made eating disorders worse and increased suicidal ideation among teen girls. Against this backdrop of relentless innovation to maximize engagement and ad spending, Zuckerberg’s frequent claims that monitoring hate speech or misinformation at scale was “too difficult” or “technically impossible” ring hollow. How could it be impossible to monitor hate speech while simultaneously keeping tabs on when teen girls are feeling insecure? The truth is, when it came to growing revenue and profits, Facebook demonstrated immense ingenuity and problem-solving power; when it came to safeguarding democracy or human dignity, the company suddenly discovered its limits. The damage inflicted by Facebook is so sweeping, so deeply intertwined with human rights abuses and national security threats, it should force us to reconsider—or at least raise significant questions about—whether growth itself is a valid goal. Mark Zuckerberg didn’t just build a tech giant; he built a cautionary tale. The title of Wynn-Williams’s book is from The Great Gatsby and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s indictment of characters Tom and Daisy, who “smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness.” The parallel with Zuckerberg and Sandberg is clear. But Careless People should also spark deeper consideration of how our growth-obsessed capitalist system leads to perverse incentives, catastrophic externalities, and systems that cannibalize the very societies they rely upon. Similarly, The Great Gatsby isn’t just a discussion of the poor morals and behaviors of the upper classes in the Roaring Twenties—it’s also a critical perspective on the social and economic transformation in America at that time. Skepticism of the “growth-at-all-costs” logic that underpins today’s capitalism is often dismissed as fringe thinking. As ecological economist Tim Jackson observes, “Questioning growth is deemed the act of lunatics, idealists, and revolutionaries.” Yet what alternative is left when companies like Meta repeatedly erode public trust, mental health, and democratic institutions in pursuit of investor returns? Degrowth, a growing movement in response to runaway capitalism, has been gaining attention as an urgently needed alternative—one that rejects expansion as an end in itself and instead redefines progress around well-being rather than accumulation: shorter working hours, universal basic services, caps on resource extraction, and new models of enterprise that are accountable to people and the planet. Companies like Patagonia and Fairphone are already showing what some of these princip

The recent exposé Careless People, by former Facebook (now Meta) executive Sarah Wynn-Williams, has received significant attention for its jaw-dropping revelations about the social media company and its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg. According to the author, company decisions enabled the Chinese Communist Party to suppress dissent, undermined the mental health of teenage girls, and led to genocide in Myanmar and election interference in the U.S.

While there has been much attention to details showing the moral bankruptcy of Zuckerberg and former COO Sheryl Sandberg, there has been less discussion of how financial pressures shaped executives’ decisions. Are Meta’s leaders just “bad apples,” or are the many troubling revelations in Careless People representative of pervasive problems across corporate America?

While Careless People focuses on Facebook, it also prompts a broader reflection on the tech industry as a whole. Companies like Amazon, X, Google, YouTube, TikTok, and many others similarly operate extractive growth models that prioritize engagement, surveillance, and monetization over social responsibility. What Wynn-Williams has laid bare is a shared playbook of scale over ethics.

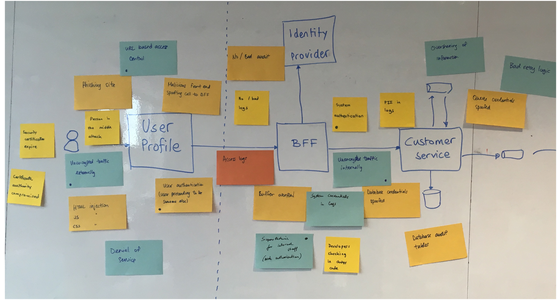

Facebook’s meteoric rise—and the ethical corners cut by its leaders to meet its goals—reveals fatal flaws at the heart of growth-obsessed capitalism. The company had a vast infrastructure overseen by a chief growth officer operating “. . . fast and loose, and always looking for opportunities in the gray area created by the lack of regulation.” When Facebook reached 1 billion users, COO Javier Olivan (who succeeded Sandberg) expressed fear and uncertainty, not pride and accomplishment, because it meant the company had to figure out things “like how to reach children, how to get into places like China that are hostile to any social media site.”

The company engineered algorithms to maximize time spent on the platform—regardless of whether that meant radicalizing users, fostering election misinformation, or taking advantage of people’s vulnerability. Even when Facebook became a trillion-dollar company, internal discussions continued to emphasize seizing vulnerable markets (like teenagers experiencing mental health crises) because these were deemed “high-value” audiences. In internal documents, Facebook acknowledged that its platforms made eating disorders worse and increased suicidal ideation among teen girls.

Against this backdrop of relentless innovation to maximize engagement and ad spending, Zuckerberg’s frequent claims that monitoring hate speech or misinformation at scale was “too difficult” or “technically impossible” ring hollow. How could it be impossible to monitor hate speech while simultaneously keeping tabs on when teen girls are feeling insecure? The truth is, when it came to growing revenue and profits, Facebook demonstrated immense ingenuity and problem-solving power; when it came to safeguarding democracy or human dignity, the company suddenly discovered its limits.

The damage inflicted by Facebook is so sweeping, so deeply intertwined with human rights abuses and national security threats, it should force us to reconsider—or at least raise significant questions about—whether growth itself is a valid goal. Mark Zuckerberg didn’t just build a tech giant; he built a cautionary tale.

The title of Wynn-Williams’s book is from The Great Gatsby and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s indictment of characters Tom and Daisy, who “smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness.” The parallel with Zuckerberg and Sandberg is clear.

But Careless People should also spark deeper consideration of how our growth-obsessed capitalist system leads to perverse incentives, catastrophic externalities, and systems that cannibalize the very societies they rely upon. Similarly, The Great Gatsby isn’t just a discussion of the poor morals and behaviors of the upper classes in the Roaring Twenties—it’s also a critical perspective on the social and economic transformation in America at that time.

Skepticism of the “growth-at-all-costs” logic that underpins today’s capitalism is often dismissed as fringe thinking. As ecological economist Tim Jackson observes, “Questioning growth is deemed the act of lunatics, idealists, and revolutionaries.” Yet what alternative is left when companies like Meta repeatedly erode public trust, mental health, and democratic institutions in pursuit of investor returns?

Degrowth, a growing movement in response to runaway capitalism, has been gaining attention as an urgently needed alternative—one that rejects expansion as an end in itself and instead redefines progress around well-being rather than accumulation: shorter working hours, universal basic services, caps on resource extraction, and new models of enterprise that are accountable to people and the planet.

Companies like Patagonia and Fairphone are already showing what some of these principles look like in practice. Patagonia’s transfer of ownership to an environmental trust ensures all profits support climate action, while Fairphone’s modular, repairable phones challenge the logic of planned obsolescence and resource waste.

Critics often dismiss degrowth as unrealistic or anti-innovation. But what’s truly delusional is believing that the endless growth obsession that fuels companies like Meta can coexist with human dignity and democratic stability. The real question isn’t whether we can afford to abandon growth. It’s whether we can afford not to.

Meta’s history confirms the urgency of making this shift. Without systemic limits, the pursuit of scale inevitably erodes the conditions necessary for a free and flourishing society. Had Meta been judged by measures like user safety, informational integrity, or ethical design—instead of engagement and ad revenue—the world would be a safer and saner place today. It’s time for policymakers to recognize this and start asking harder questions: Growth for whom? At what cost? To what end?

![[The AI Show Episode 150]: AI Answers: AI Roadmaps, Which Tools to Use, Making the Case for AI, Training, and Building GPTs](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20150%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 149]: Google I/O, Claude 4, White Collar Jobs Automated in 5 Years, Jony Ive Joins OpenAI, and AI’s Impact on the Environment](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20149%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The All-in-One CompTIA Certification Prep Courses Bundle (90% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![How to Survive in Tech When Everything's Changing w/ 21-year Veteran Dev Joe Attardi [Podcast #174]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1748483423794/0848ad8d-1381-474f-94ea-a196ad4723a4.png?#)

_ArtemisDiana_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Sonos Father's Day Sale: Save Up to 26% on Arc Ultra, Ace, Move 2, and More [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97469/97469/97469-640.jpg)

![Apple 15-inch M4 MacBook Air On Sale for $1023.86 [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97468/97468/97468-640.jpg)