Stablecoins Are a Monetary Revolution in the Making

Marvin Barth says pegged cryptocurrencies could effectively create “narrow banking”: a long-held dream of economists looking to separate critical financial functions.

We may be on the verge of a revolution in monetary finance that is the century-long dream of many prominent economists. Financial innovation is laying the foundation for their dream just as the U.S. political economy is shifting to support it. This revolution, if it proceeds, has major implications for global finance, economic development, and geopolitics, and will create many winners and losers. The shift I’m referring to is “narrow banking” built on stablecoins. If those are unfamiliar concepts to you, let me review 800 years of financial innovation in 500 words.

The origins of fractional reserve banking

Our current financial system is built on the concept of fractional-reserve banking. In the 13th and 14th century, Italian money changers cum bankers began to figure out that because depositors (rarely) demand their money back at the same time, they could hold only a fraction of the coin needed to back their deposits. Not only was this more profitable but it also facilitated payments across great distances: rather than send gold coins over dangerous roads, a Medici in Florence need only sent a letter to his agent in Venice instructing him to debit one account and credit another.

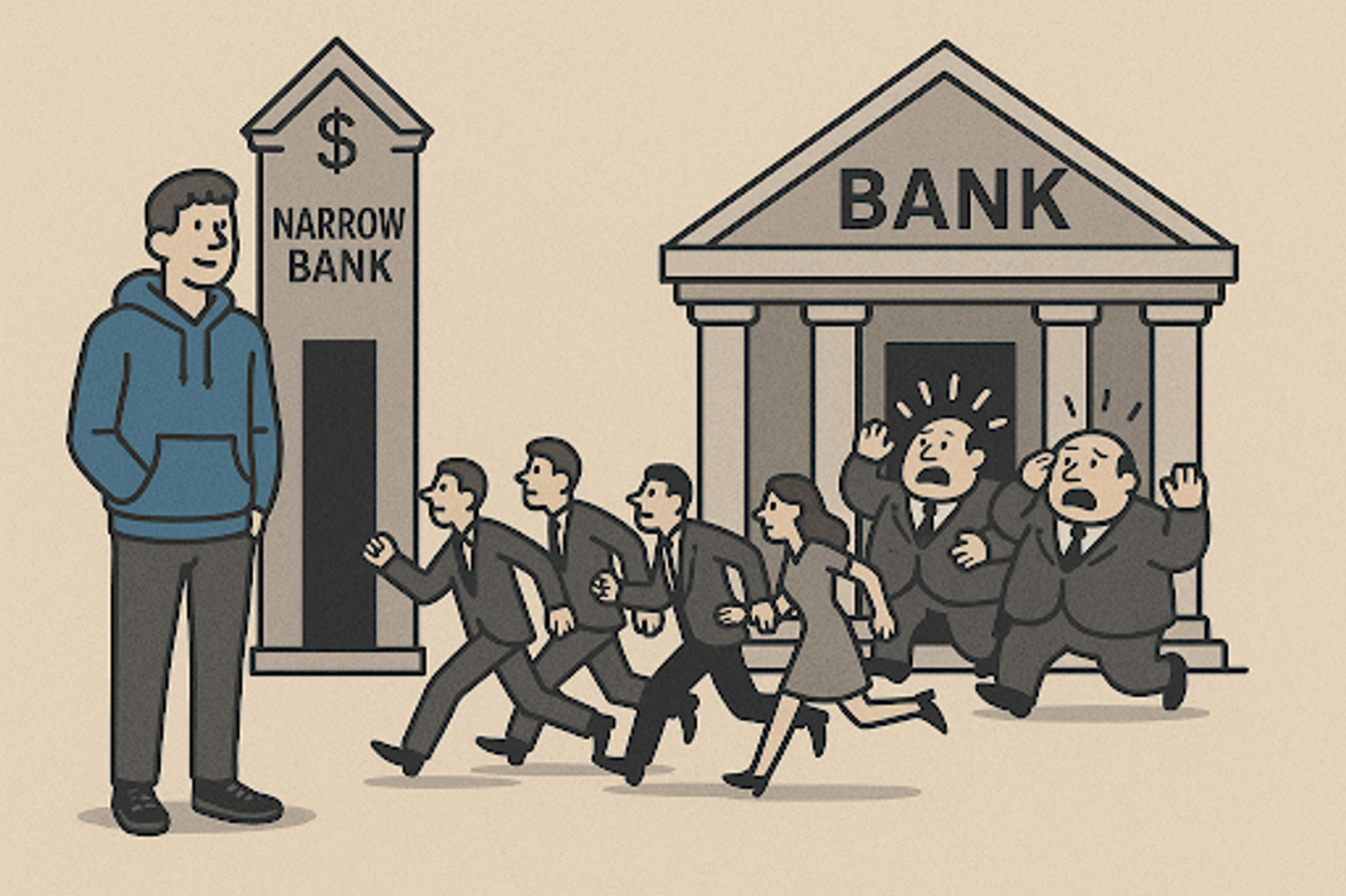

Though highly profitable and effective for payments in normal circumstances, fractional reserve banking has a downside. Its inherent leverage makes the system unstable. A downturn in the economy might cause more depositors to withdraw savings at once, or worse, generate rumors that the loans backing banks’ deposits are going to default, causing a “run” on the bank. A bank unable to meet its depositors’ demands collapses into bankruptcy. But more than just depositors’ wealth is lost when banks fail in a fractional reserve system. Because banks both generate credit and facilitate payment, economic activity is severely constricted when banks fail since payment for goods and services is impaired and lending isn’t available for new investment.

Governments attempt to fix its problems

Over the centuries, as banks became simultaneously more leveraged and more critical to economic functioning, governments stepped in to try to reduce the risks of banking crises. In 1668, Sweden chartered the first central bank, the Riksbank, to lend to other banks experiencing runs. The Bank of England followed 26 years later. While that helped solve liquidity problems (banks with good assets but insufficient cash), it didn’t stop solvency crises (banks with bad loans). The U.S. created deposit insurance in 1933 to help stop solvency-based bank runs, but as illustrated by the many banking crises since, including the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis in 2008, neither deposit insurance nor bank capital regulations solved fractional reserve banking’s endemic fragility. Government intervention reduced only the frequency of crises and shifted their costs from depositors to taxpayers.

Economists build a better mousetrap

Around the time that the Roosevelt Administration was introducing deposit insurance, some of the era’s top names in economics at the University of Chicago were hatching a different solution: the so-called Chicago Plan, or “narrow banking.” During the U.S. savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s the idea had a resurgence among economists.

Narrow banking solves the central problem of fractional reserve banking by separating the critical functions of payments and money creation from credit creation. Many people think that central banks create money. But that’s not true in a fractional reserve system: banks do. Central banks manage the rate at which banks manufacture money (by controlling their access to reserves), but money is created by banks whenever they lend money, magically generating corresponding deposits in the process. This system – and its chaotic unwind – ties money growth to credit growth, and through banks’ network effects, to payments.

Splitting banks in two

The Chicago Plan separates the critical functions of money creation and payments from credit by splitting banking functions in two. “Narrow” banks that accept deposits and facilitate payments are required to back their deposits one for one with safe instruments like T-bills or central bank reserves. Think of them like a money market fund with a debit card. Lending is done by “broad” or “merchant” banks that fund themselves with equity capital or long-term bonds, hence aren’t subject to runs.

This segmentation of banking makes each function safe from the others. Deposit runs are eliminated because they are fully backed by high-quality assets (as well as access to the central bank). Since narrow banks facilitate payments, their safety removes the risk to the payments system. Because money is no longer created by credit creation, bad lending decisions at merchant banks don’t affect the money supply, deposits or payments. Conversely, neither natural fluctuations in the economy’s demand for money – booms or recessions – nor concerns over loan quality affect merchant banks’ lending because it is funded with long-term debt and equity.

But why didn’t we adopt this wonderful solution?

You may be asking yourself now, “If narrow banking is so wonderful, why don’t we have it today?” The answer is twofold: the transition is painful and there has never been a political economy to support legislation to make the change.

Because narrow banking requires 100% backing of deposits by either T-bills or central bank reserves, the transition to narrow banking would require existing banks to either call in their loans, shrinking the money supply dramatically, or if they could find non-bank buyers, sell off their loan portfolios to buy short-term government paper. Both would precipitate a massive credit crunch, and the former would create liquidity shortages and payments problems.

As to the political economy, fractional reserve banking is extremely profitable – “a license to steal” as my father calls it (admiringly) – and generates a lot of jobs. Economists, in contrast, are a small group that are questionably employed themselves. As anyone in Washington, DC will tell you, the American Bankers Association (ABA) is among the most powerful lobbies in town. The same play with different actors runs in London, Brussels, Zürich, Tokyo, et cetera. Hence the continuance of fractional reserve banking is not a banking conspiracy; it’s just been good politics and cautious economics.

Financial innovation meets shifting politics

That may no longer be so. Both the costs of transition and the political economy have changed, particularly in the U.S. Developments in decentralized finance – a.k.a. “DeFi” or “crypto” – and the coincident evolution of the U.S. political economy, national interests, and financial structure have generated conditions that make a shift to narrow banking in the U.S. not only feasible, but increasingly likely in my view.

Let’s start with the critical DeFi development: the rapid growth of stablecoins. Stablecoins are decentralized “digital dollars” (or euros, yen, et cetera). Unlike central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) that are issued, cleared and settled centrally by central banks, stablecoins are privately created “digital tokens” (electronic records). Like cryptocurrencies, ownership and transactions are stored and cleared through blockchain technology on distributed ledgers (decentralized registries). The combination of blockchain immutability and universally replicated registries facilitates trust between unknown parties without a government guarantee.

Stablecoins differ from cryptocurrencies in being pegged to fiat currencies, gold or other stores of value that are more “stable” than bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. They were designed to be on- and off-ramps between the traditional world of fiat money and the blockchain-based world of DeFi and cryptocurrencies, and to provide a steady “on-blockchain” unit of account to facilitate DeFi trading. But stablecoins’ use case has evolved significantly amid spectacular growth in acceptance and usage. Stablecoin annual transaction volumes through March totalled $35 trillion, more than doubling the prior 12-month period, while users have increased more than 50% to over 30 million, and the outstanding value of stablecoins has hit $250 billion.

More than 90% of stablecoin transactions still involve either on/off-ramping or DeFi trading, but an increasing share of transaction growth involves “real world” uses. Person-to-person and business transactions in countries with unstable local currencies, like Argentina, Nigeria and Venezuela, have been a key source of growth, but one of the largest has been increasing use in global remittances by migrant labor, over a quarter of the total according to one estimate.

With the help of Congress

Stablecoins’ increasingly rapid acceptance and growth as an alternative payments system is coming just as the Trump Administration and Congress are moving to institutionalize them.

How do stablecoins maintain their value versus a particular currency like the dollar? In theory each stable coin unit is backed one for one with the currency it is pegged to. In practice, this hasn’t always been the case. But the U.S. legislation defines what are acceptable high-quality, liquid assets (HQLA), mandates one-for-one backing and requires regular audits to establish compliance. Thus, Congress is creating the legal basis for entities that (1) take deposits; (2) are required to fully back deposits by HQLA; and (3) facilitate payments in the economy.

Deja vu

Does that sound familiar to you? Isn’t that a narrow bank?

There are a few missing pieces. Most notably that neither the GENIUS nor STABLE Acts grant stablecoin issuers access to the Federal Reserve and neither defines stablecoins as money for tax purposes. The omission of access to the Fed likely reflects both necessary prudence to avoid undermining the fractional reserve banking system (too quickly) with a direct competitor and the ABA’s lobbying efforts to protect banks’ monopoly. But even here there are intriguing breadcrumbs that hint banks’ protection may be temporary and only long enough to transition to a narrow banking model: among the approved HQLA for stablecoin issuers in both bills are reserves at the Federal Reserve, currently accessible only by banks.

Shifting political sands

Both the Trump campaign’s pivot to crypto last year and both houses of Congress moving to normalize stablecoins reflects a profound shift in America’s domestic political economy and its sense of national interests. Bipartisan populist anger at banks and their relationship with Washington hasn’t dissipated since the Global Financial Crisis. The Fed’s QE and recent inflationary policy errors have only increased populist fury. This is just as much a part of the crypto phenomenon as FOMO.

But crypto also has generated immense new wealth and opportunities for business, creating a well financed rival to the ABA. Even institutional asset managers now are diverging with their traditional allies in banking, salivating at the opportunities they see in DeFi. The combination of popular base and economic muscle is creating, for the first time, a political economy supportive of narrow banking.

Further, the U.S. now has compelling national interests in developing stablecoins. First, in a world where China (and other U.S. rivals) increasingly seek to displace U.S. payment systems like SWIFT with their own, an independent, third-party payment system that prevents countries from being “trapped” in a Chinese payments system is appealing. The other national interest is the one that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent keeps mentioning: a systemic shift towards stablecoin-based narrow banking creates “one of the largest buyers of U.S. T-bills.”

And the new financial architecture

U.S. financial structure has become far more conducive to a non-disruptive transition relative to any time in its history, or relative to other countries today, giving it an advantage over rivals. While the U.S. has long been less bank dependent for credit than other major economies due to its greater use of corporate bond markets and securitized mortgages, the growth of so-called “shadow” banking in the last two decades has made it even more so. Bank credit in the U.S. is little more than a third of total credit to the private non-financial sector. The rest is provided by bond markets and the shadow sector that are in fact the broad or merchant banks envisioned under the Chicago Plan.

The economic, geopolitical and financial implications of a shift to stablecoin-based narrow banking in the United States are huge. It would create significant winners and losers both within the U.S. and around the world.

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

![GrandChase tier list of the best characters available [June 2025]](https://media.pocketgamer.com/artwork/na-33057-1637756796/grandchase-ios-android-3rd-anniversary.jpg?#)

.jpg?#)

_ArtemisDiana_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Latest leak shows how Galaxy Z Flip 7 FE compares to the standard Flip 7 [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/galaxy-z-flip-7-fam-blass-1.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple in Last-Minute Talks to Avoid More EU Fines Over App Store Rules [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97680/97680/97680-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds tvOS 26 Beta 2 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97691/97691/97691-640.jpg)