When it comes to logos, these numbers are the most popular

This month’s legal dustup between NFL quarterback Lamar Jackson and NASCAR legend Dale Earnhardt Jr. over trademark rights to the number 8 may have amounted to little more than a tempest in a teapot, but it has drawn attention to a rarely considered topic in branding and marketing: the use of numbers in brand names and logos. Why might a seemingly arbitrary number like 8—or 27 or 63, for that matter—be worth fighting over? And are some numbers worth more than others? Obviously, numbers are at an important disadvantage compared to letters when it comes to their use as trademarks. While an initial letter can stand for any word that it begins with, numbers are much more constrained in their ability to represent a range of meanings. This helps explain why an examination of U.S. Patent and Trademark Office records shows that, over time, there have been a total of 7,183 trademark applications for logos consisting solely of a stylized letter A—whether traditional or crossbar-less—while the most popular number (1, naturally) has garnered just 466 such logo applications. So it’s rare for numbers to stand alone as trademarks. They often serve as supporting elements in brand names, (Heinz 57, Phillips 66), or worse (Nike’s would-be moniker, Dimension 6). USPTO data reveals, surprisingly, that in trademarks that are simply names, with no graphic elements, the most commonly used number between 0 and 100 is 2, which edges ahead of 1 perhaps in part due to its ability to represent the word to in a name. Next come 4, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 100, with poor number 8—so hotly contested by Jackson and Earnhardt—relegated to 11th place. The bottom of the list is populated by the apparently uninspiring 87, 67, 82, 89, and, last of all, 83. Some numbers are able to function as trademarks by playing off meanings that have already been baked into them. Both the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers and 76 gas stations (shortened from the more descriptive Union 76) strike patriotic chords by referring to the U.S.’s 1776 founding (although the latter also nods to the fuel’s original 76 octane rating). When no such meaning is obvious, numbers used as trademarks are like empty vessels that can be laden with significance only through some combination of time and heavy brand lifting. Take 84 Lumber: Its name is essentially arbitrary, stemming from the company’s location in the village of Eighty Four, Pennsylvania, which itself is named after . . . well, no one is quite sure. But after 69 years in business, 84 Lumber more or less “owns” the number 84. Part of the appeal of such seemingly random numbers is their mystery, and the accompanying tease that they might hold some secret meaning. This explains the popularity of the use of area codes as trademarks, and hints at why Rolling Rock continues to emblazon a 33 on each of its beer bottles. But for brands more interested in distinctiveness than riddles, perhaps the best way to employ a number as a trademark is to express it in the form of a unique logo design, making it not a mere number, but a stylized numeral. The result can be a powerful symbol, particularly for types of businesses where identifying numbers have an outsize importance, like television stations (see WABC New York’s 63-year-old “Circle 7” mark), banks (Cincinnati’s Fifth Third Bank has a delightful improper fraction for a logo), and, yes, racing concerns like NASCAR (where Dale Jr. emerged from his recent kerfuffle with the rights to the iconic “Budweiser 8”). Adopting an unusual design motif can help a brand lay claim to even the most common of numerals, as Builders FirstSource has done with its oddly tilted 1. As noted above, 1 is the most prevalent stylized logo number in the USPTO’s files. After that, though, come 7 and the coveted 8, suggesting a particular visual appeal in the form of these numerals. Following along are 3, 5, 2, 4, 9, and 6, before the first double-digit number, the aforementioned 76. Repeating digits seem popular in logos; 33 comes in at 14th, and 99 at 19th, for instance. Meanwhile, the most unpopular numbers are 71, 87, and 94, with only one logo trademark application apiece. But perhaps in these unloved numbers there are opportunities for brands to acquire an ownable set of digits that they won’t have to tussle over.

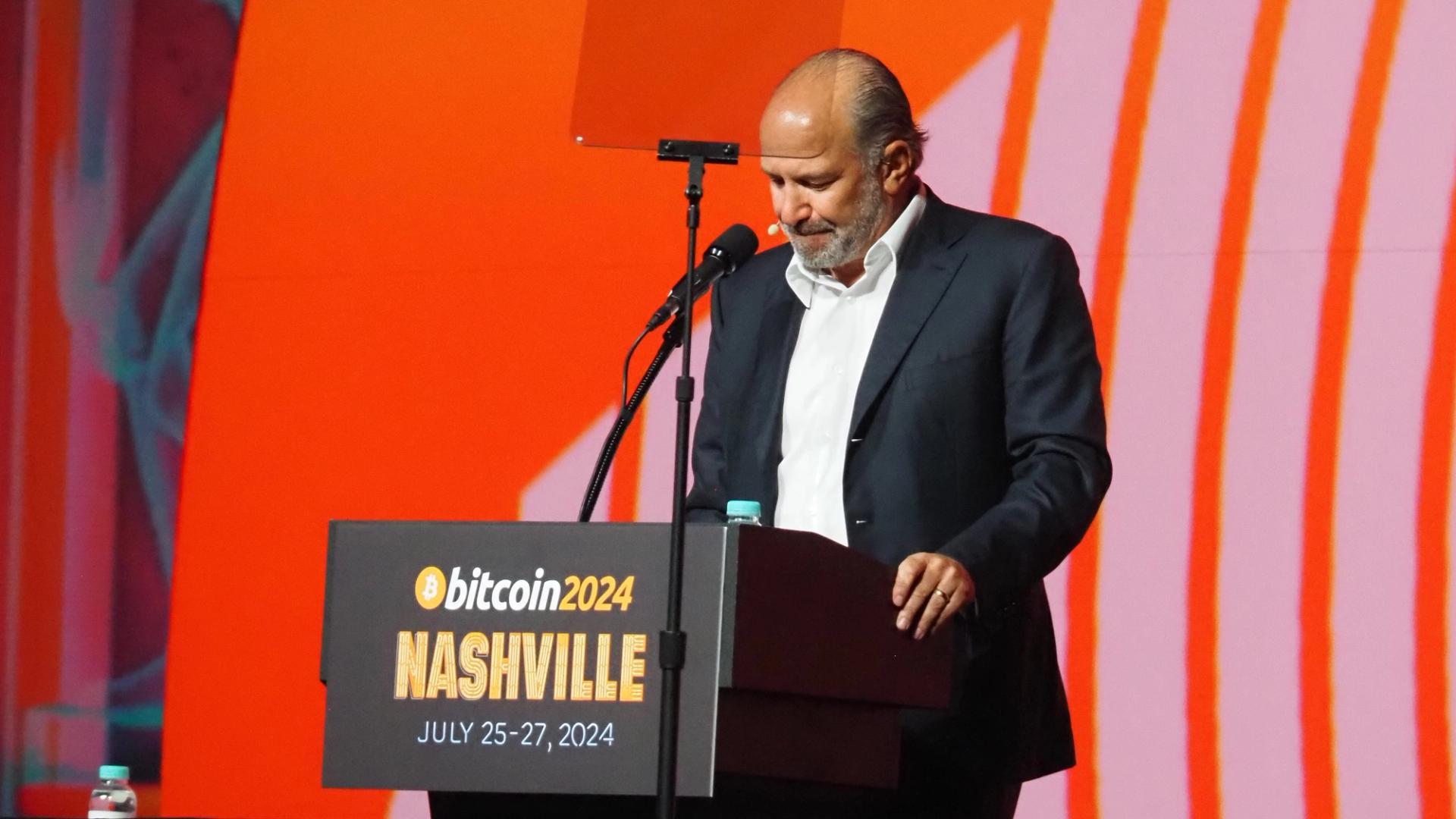

This month’s legal dustup between NFL quarterback Lamar Jackson and NASCAR legend Dale Earnhardt Jr. over trademark rights to the number 8 may have amounted to little more than a tempest in a teapot, but it has drawn attention to a rarely considered topic in branding and marketing: the use of numbers in brand names and logos. Why might a seemingly arbitrary number like 8—or 27 or 63, for that matter—be worth fighting over? And are some numbers worth more than others?

Obviously, numbers are at an important disadvantage compared to letters when it comes to their use as trademarks. While an initial letter can stand for any word that it begins with, numbers are much more constrained in their ability to represent a range of meanings. This helps explain why an examination of U.S. Patent and Trademark Office records shows that, over time, there have been a total of 7,183 trademark applications for logos consisting solely of a stylized letter A—whether traditional or crossbar-less—while the most popular number (1, naturally) has garnered just 466 such logo applications.

So it’s rare for numbers to stand alone as trademarks. They often serve as supporting elements in brand names, (Heinz 57, Phillips 66), or worse (Nike’s would-be moniker, Dimension 6). USPTO data reveals, surprisingly, that in trademarks that are simply names, with no graphic elements, the most commonly used number between 0 and 100 is 2, which edges ahead of 1 perhaps in part due to its ability to represent the word to in a name. Next come 4, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 100, with poor number 8—so hotly contested by Jackson and Earnhardt—relegated to 11th place. The bottom of the list is populated by the apparently uninspiring 87, 67, 82, 89, and, last of all, 83.

Some numbers are able to function as trademarks by playing off meanings that have already been baked into them. Both the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers and 76 gas stations (shortened from the more descriptive Union 76) strike patriotic chords by referring to the U.S.’s 1776 founding (although the latter also nods to the fuel’s original 76 octane rating). When no such meaning is obvious, numbers used as trademarks are like empty vessels that can be laden with significance only through some combination of time and heavy brand lifting. Take 84 Lumber: Its name is essentially arbitrary, stemming from the company’s location in the village of Eighty Four, Pennsylvania, which itself is named after . . . well, no one is quite sure. But after 69 years in business, 84 Lumber more or less “owns” the number 84.

Part of the appeal of such seemingly random numbers is their mystery, and the accompanying tease that they might hold some secret meaning. This explains the popularity of the use of area codes as trademarks, and hints at why Rolling Rock continues to emblazon a 33 on each of its beer bottles.

But for brands more interested in distinctiveness than riddles, perhaps the best way to employ a number as a trademark is to express it in the form of a unique logo design, making it not a mere number, but a stylized numeral. The result can be a powerful symbol, particularly for types of businesses where identifying numbers have an outsize importance, like television stations (see WABC New York’s 63-year-old “Circle 7” mark), banks (Cincinnati’s Fifth Third Bank has a delightful improper fraction for a logo), and, yes, racing concerns like NASCAR (where Dale Jr. emerged from his recent kerfuffle with the rights to the iconic “Budweiser 8”). Adopting an unusual design motif can help a brand lay claim to even the most common of numerals, as Builders FirstSource has done with its oddly tilted 1.

As noted above, 1 is the most prevalent stylized logo number in the USPTO’s files. After that, though, come 7 and the coveted 8, suggesting a particular visual appeal in the form of these numerals. Following along are 3, 5, 2, 4, 9, and 6, before the first double-digit number, the aforementioned 76. Repeating digits seem popular in logos; 33 comes in at 14th, and 99 at 19th, for instance. Meanwhile, the most unpopular numbers are 71, 87, and 94, with only one logo trademark application apiece. But perhaps in these unloved numbers there are opportunities for brands to acquire an ownable set of digits that they won’t have to tussle over.

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![Did I Discover A New Programming Paradigm? [closed]](https://miro.medium.com/v2/resize:fit:1200/format:webp/1*nKR2930riHA4VC7dLwIuxA.gif)

-Classic-Nintendo-GameCube-games-are-coming-to-Nintendo-Switch-2!-00-00-13.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Wavebreakmedia_Ltd_FUS1507-1_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![New iPhone 17 Dummy Models Surface in Black and White [Images]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97106/97106/97106-640.jpg)

![Hands-On With 'iPhone 17 Air' Dummy Reveals 'Scary Thin' Design [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97100/97100/97100-640.jpg)