How to Refactor Complex Codebases – A Practical Guide for Devs

Developers often see refactoring as a secondary concern that they can delay indefinitely because it doesn’t immediately contribute to revenue or feature development. And managers frequently view refactoring as "not a business need" until it boils ove...

Developers often see refactoring as a secondary concern that they can delay indefinitely because it doesn’t immediately contribute to revenue or feature development.

And managers frequently view refactoring as "not a business need" until it boils over and becomes the most significant business need possible.

"Oh, our software somehow works. We can't implement any new changes. And oh, everyone is quitting because work is miserable."

In this article, I’ll walk you through the steps I use to refactor a complex codebase. We’ll talk about setting goals, writing tests, breaking up monoliths into smaller modules, verifying changes, making sure existing features still work, and keeping tabs on performance. I’ll also show you how to speed up reviews using AI tools.

By following these steps, you can turn complex, fragile code into a clean, reliable codebase your team can own.

The Issue of Technical Debt

As projects grow and evolve, technical debt increases. Code that was once functional and manageable turns into an unmaintainable mess, where even small changes become risky and time-consuming.

Despite the obvious need for cleanup, refactoring rarely gets prioritized because there's always something more urgent, new features, bug fixes, and client demands.

I’ve had conversations with engineers, many of whom are working on enterprise software and are fully aware of their codebase's code smells and inconsistencies. They dislike the situation but feel powerless to change it.

So how do we shift from a culture of writing for pure functionality to a culture that values maintainability, especially for complex codebases?

It’s usually a mistake to completely halt new feature development for a long refactoring period (except perhaps in emergencies). Business needs still exist, and putting everything on hold can create tension and lost opportunities. It’s better to find a balance so you’re still delivering value to users even as you clean under the hood.

While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, a structured approach can help teams introduce sustainable refactoring practices, even in environments where management is resistant. Let’s explore how this works.

Table of Contents:

What is Refactoring?

Many people all too often use the word "refactor" when they mean a targeted rewrite.

As Martin Fowler famously said,

“Refactoring is a controlled technique for improving the design of an existing code base. Its essence is applying a series of small behavior-preserving transformations... However, the cumulative effect... is quite significant.”

In practice, this means continuously polishing code to reduce complexity and technical debt.

While traditional software development follows a linear approach of designing first and coding second, real-world projects often evolve in ways that lead to structural decay. Refactoring counteracts this by continuously refining the codebase, transforming disorganized or inefficient implementations into well-structured, maintainable solutions.

A targeted rewrite is a focused overhaul of a specific aspect of an application, often affecting multiple parts of the codebase. It carries more risk than refactoring but is still controlled and contained.

Preparing for Refactoring

Even the most skilled refactoring effort can stall without proper preparation. Before you start moving code around, laying a foundation that will keep your work organized and your team on the same page is crucial.

Here are some steps you can take to ensure your refactoring efforts are successful.

Secure Management Buy-in

As I’ve already discussed, getting time for refactoring can be difficult in feature-driven organizations. Often, management will accept refactoring investment if you can tie it to business outcomes, faster time to market, fewer outages (which translates to happier customers), and the ability to take on new initiatives.

Make those connections explicit. For example, you could say:

“If we refactor our reporting engine now, it will make it feasible to add the analytics module next quarter, which unlocks a new revenue stream.”

Or use data:

“We spent 30% of our last sprint fixing bugs in module Y. After refactoring Y, we expect that to drop significantly, freeing time for new features.”

Business-minded arguments help justify the balance.

Ensure a Safety Net with Automated Testing

As you refactor, tests are your safety net. Before modifying a component, write characterization tests around it if they don’t exist.

# example: characterization test for a legacy function

def legacy_calculate_discount(price, rate):

# ... complex logic you don't fully understand yet ...

return price * (1 - rate/100) if rate < 100 else 0

def test_legacy_calculate_discount():

# capture existing behavior

assert legacy_calculate_discount(100, 10) == 90

assert legacy_calculate_discount(50, 200) == 0

These tests capture the current behavior, so you’ll know if you accidentally change it. Unit tests, integration tests, and e2e tests all validate that refactoring hasn’t broken anything.

It’s often worth investing time in setting up a continuous integration pipeline so that every change triggers automated tests. This gives rapid feedback and confidence that you’re not introducing regressions. Robust testing and CI/CD enable you to move faster and refactor with peace of mind.

# .github/workflows/ci.yml

name: CI

on: [push, pull_request]

jobs:

test:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

- uses: actions/setup-python@v4

with: python-version: '3.10'

- run: pip install -r requirements.txt

- run: pytest --maxfail=1 --disable-warnings -q

Identify High-Risk Areas

The first step is to figure out what to refactor. High-risk areas are parts of the code likely to cause bugs or slow development. Common signs include long methods, large classes, duplicate code, and complex conditional logic.

Such code “smells” often hint at deeper design problems. Tools like static analysis can automatically flag these issues.

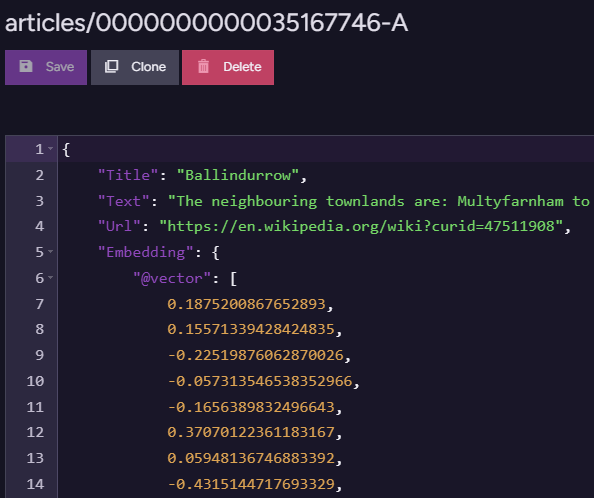

For example, SonarQube will mark code smells (like high complexity or long methods) that increase technical debt. Using SonarQube or similar tools, you can generate reports on code complexity (for example, cyclomatic complexity metrics) and find hotspots in the codebase that need more attention.

Set Clear Refactoring Goals

Before refactoring code, define the goal.

Goals must be specific and measurable. For example, you might aim to reduce a class’s size or a function’s cyclomatic complexity by a certain amount or to increase unit test coverage from 60% to 90%.

Each goal is tied to a measurable outcome: shorter methods, fewer if statements or classes with a single responsibility, faster execution for processing orders, higher test coverage, and no unused code. These targets will guide our refactoring plan and let us verify when we’ve succeeded.

Tip: Write down your refactoring goals and share them with your team. This sets expectations that you’re not adding new features in this effort, just making the code cleaner and more robust. It also helps justify the time spent by showing the benefits (like more straightforward future additions and fewer bugs).

Techniques for Refactoring Complex Codebases

1. Identifying and Isolating Problem Areas

It can be overwhelming to decide where to start refactoring a large codebase. Not every part of the code needs refactoring – some areas are delicate or rarely touched.

The most impactful refactoring efforts typically target the “problem areas”: parts of the codebase that are overly complex, error-prone, or act as bottlenecks for development and performance. Identifying these areas is a crucial first step.

Techniques for Finding Hotspots

Team knowledge & developer frustration

Don’t underestimate the value of anecdotal information from the team. Which parts of the code do developers dread working in? Often, the team’s instincts point to areas that are hard to understand or modify (for example, “the accounting module is a black box, we hate touching it”). These could be areas to improve.

In my experience, simply asking, “If you had a magic wand, which part of the code would you rewrite?” yields very insightful answers.

Code complexity metrics

Use static analysis tools to measure cyclomatic complexity, code duplication, large functions/classes, and so on. Files or modules with extremely high complexity numbers or thousands of lines are good candidates for scrutiny. But static complexity alone doesn’t tell the whole story – a file might be ugly but rarely touched.

Change frequency (Churn)

Look at version control history to see which files are often changed, especially those associated with bug fixes or incidents.

Hotspot analysis

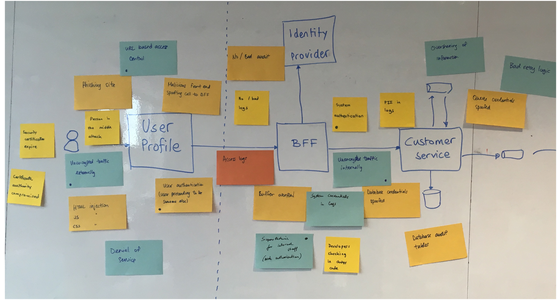

A robust approach combines complexity and change frequency to find “hotspots.” For example, a tool or technique plotting modules by their complexity and how often they change can highlight the problematic areas. CodeScene (a code analysis tool) popularized this: hotspots are parts of the code that are highly complex and frequently modified, indicating areas where “paying down debt has a real impact”.

If a module is a mess and developers are in it every week, improving that module will likely yield outsized benefits (fewer bugs, faster adds).

Performance bottlenecks and crashes

Some parts of the codebase become targets for refactoring because they cause frequent performance problems or outages. For instance, if a specific service or job crashes often or can’t keep up with the load, you might need to refactor it for stability.

How to Isolate Problem Areas

Once you’ve identified a hotspot or problem area, the next challenge is isolating it so you can refactor safely. In a complex system, nothing lives in complete isolation. That problematic module likely interacts with many others.

Here are strategies to isolate and tackle it:

Break dependencies (Create seams)

Michael Feathers (in Working Effectively with Legacy Code) introduced the concept of “seams” – places where you can cut into a codebase to isolate a part for testing or refactoring. This might mean introducing an interface or abstraction between components so you can work on one side independently.

For example, suppose PaymentService is tightly coupled to StripeGateway, with direct calls scattered throughout the code.

# payment_service.py

def charge_customer(order_id, amount):

# Hardcoded dependency to Stripe

stripe = StripeGateway()

stripe.charge(order_id, amount)

To isolate and refactor the payment logic safely, you can introduce a PaymentProcessor interface and have PaymentService depend on that interface instead. Then, create an adapter like StripeAdapter that implements PaymentProcessor and delegates to the existing Stripe logic.

This way, you can safely refactor or even replace the Stripe integration behind the StripeAdapter without impacting PaymentService or any other module that uses it. As long as the PaymentProcessor interface is honored, the rest of the system remains unaffected.

# interfaces.py

class PaymentProcessor:

def charge(self, order_id, amount):

raise NotImplementedError

# stripe_adapter.py

class StripeAdapter(PaymentProcessor):

def charge(self, order_id, amount):

# Internally still uses Stripe

stripe = StripeGateway()

stripe.charge(order_id, amount)

# payment_service.py (Refactored)

class PaymentService:

def __init__(self, processor: PaymentProcessor):

self.processor = processor

def charge_customer(self, order_id, amount):

self.processor.charge(order_id, amount)

“Branch-by-abstraction”

This technique is related to the above and is often used in continuous delivery. The idea is to add a layer of abstraction (like an interface or proxy) in front of the old code, have both old and new code implementations behind it, and then gradually shift usage from the old to the new implementation. For a while, you might have a temporary state where both versions exist (perhaps toggled by a config or feature flag).

This is similar to how the strangler fig pattern works at an architectural level. It’s a bit of extra work (since you maintain two paths for a while), but it allows you to migrate functionality and fall back if needed incrementally.

Aim to identify the 20% of the code causing 80% of the problems. Focus your refactoring energy there for maximum impact. When you do, create a plan to isolate that area via abstractions, interfaces, modules, or other means so that you can work on it with minimal risk of side effects. The more you can contain the blast radius of a refactoring, the more confidently you can move forward.

2. Incremental vs. Big Bang Refactoring

One of the first strategic decisions is approaching the refactor incrementally or going for a “big bang” overhaul. In most cases, an incremental approach is preferable, but there are scenarios where more significant coordinated refactoring steps are considered.

Let’s break down what these mean:

# before: one large function with multiple responsibilities

def process_order(order):

validate(order)

apply_discount(order)

save_to_db(order)

send_confirmation(order)

log_metrics(order)

update_loyalty_points(order)

# potentially more steps

# after: refactored incrementally into clearer, smaller units

def process_order(order):

validate(order)

apply_discount(order)

persist_and_notify(order)

def persist_and_notify(order):

save_to_db(order)

send_confirmation(order)

log_metrics(order)

update_loyalty_points(order)

Incremental refactoring

This means making small, manageable changes over time rather than attempting a massive overhaul in one shot. The system should remain functional at each step (even internally in transition). The advantage is risk mitigation: each small change is less likely to go wrong, and it’s easier to pinpoint and fix if it does.

Incremental delivery lets you confirm changes in production and makes diagnosing issues easier since you’re only changing one small thing at a time. It also means the system keeps running during the refactor, so there’s less pressure to rush to “get the system back to working condition”. If priorities shift, you can pause after some increments and still have a working product.

Big bang refactoring (Rewrite)

This is the “tear it down and rebuild” approach. You stop adding new features, possibly freeze the code for a period, and devote a considerable effort to redesigning or rewriting a significant portion (or the entirety) of the system. The idea is to emerge on the other side with a brand new, clean system.

So when (if ever) is a big bang justified? Perhaps when the existing system is truly untenable – for example, an outdated technology that must be replaced (such as a platform that can’t meet new performance or security requirements or code written in a language no longer supported). Even then, wise teams often simulate a big bang by breaking it into stages or developing the new system in parallel.

Whenever possible, favor an incremental refactoring strategy. Teams successfully pull off massive transformations by treating the big refactor as a series of mini-refactors under a shared vision.

3. Breaking Down Monolithic Code

Many complex codebases start life as a single monolithic application, one deployable, a single code project, or a tightly coupled set of modules all maintained and released together.

Over time, monoliths can become unwieldy, builds take forever, a change in one area can unintentionally affect another, and teams can be complex to scale because everyone is stepping on each other’s toes in the same code. A common refactoring challenge for senior engineers is modularising or splitting a monolith into more manageable pieces.

# define the interface

class PaymentProcessor:

def charge(self, amount): ...

# old implementation

class LegacyProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def charge(self, amount):

# original code

# new implementation behind a feature flag

class NewProcessor(PaymentProcessor):

def charge(self, amount):

# cleaner code

def get_processor():

if config.feature_new_payment:

return NewProcessor()

return LegacyProcessor()

# usage remains the same

processor = get_processor()

processor.charge(100)

Strategies for modularization.

Layer separation: Start by enforcing logical layer boundaries. For example, separate the user interface code from business logic and separate business logic from data access. In a messy monolith, these concerns often get mixed together. By organizing the code into layers (even within the same repository), you can limit the ripple effect of changes.

Domain-based modularization: If your system spans multiple business domains or functional areas, consider splitting along those lines. For example, an e-commerce monolith might be separated into modules like Accounts, Orders, Products, Shipping, and so on.

Each could become a subsystem or a package. The goal is to minimize the information these modules need to know about each other’s internals (high cohesion within modules and clear APIs between them).Microservices or services extraction: In recent years, the trend has been to break monoliths into microservices, independent services that communicate over APIs. This form of architectural refactoring can significantly improve independent deployability and scalability. But it’s a significant undertaking with complexities (distributed systems, network calls, and so on). If you decide to go this route, do it gradually.

A proven method is the strangler fig pattern mentioned earlier: you pick one piece of functionality and rewrite or extract it as a separate service, redirect traffic or calls to the new service. At the same time, the rest of the monolith remains intact and iteratively does this for other pieces.Modular monolith: Not every system needs to go full microservices. There’s an approach called a modular monolith, essentially structuring your single application into well-defined modules that communicate via explicit interfaces (almost like internal microservices but without the overhead of separate deployments).

This can give you many microservices' advantages (clear boundaries, separate development responsibility) while avoiding operational complexity.

- Identify shared utilities vs. truly independent components: In breaking down a monolith, some code is widely shared (like utility functions or cross-cutting concerns such as authentication). It might make sense to factor those into libraries or services first, as they will be needed by whatever other pieces you split out.

While breaking down a monolith, maintaining functionality during the transition is essential. Techniques like backward compatibility (discussed next) and thorough testing will be your safety net.

Finally, be prepared for the team workflow to change. If you move to microservices, teams might take ownership of different services, requiring more DevOps and communication across teams. If you keep a modular monolith, enforce code ownership or review rules to keep the modules from tangling up again (for example, you might restrict direct database access from one module to another’s tables, and so on).

4. Ensuring Backward Compatibility

A critical concern during large refactoring is: Will our changes break existing contracts?

In other words, can other systems, modules, or clients that rely on our code work as expected after we refactor? Backward compatibility is especially important if your codebase provides public APIs (to external customers or other teams), data persisted in a certain format, configuration files that users have written, etc.

Here are some strategies and considerations to maintain backward compatibility:

Suppose you have a widely-used function like send_email(to, subject, body). You want to refactor the internal logic to support additional features like HTML formatting, but you don’t want to break existing callers.

Instead of changing the function signature, you keep the public API unchanged and delegate to a new internal function:

# original API

def send_email(to, subject, body):

# send mail...

# refactored internals, keep signature

def send_email(to, subject, body):

sendv2(to=to, subject=subject, body=body)

def sendv2(to, subject, body, html=True):

# new implementation with HTML support

The internal send_email_v2() function adds new capabilities like HTML formatting, but older code using send_email() still works without any modifications.

If you're introducing a new, improved version like send_email_v2(to, subject, body, html=True), it's good practice to:

Mark the old version (send_email) as deprecated in documentation.

Ensure the old version internally calls the new one.

Give other teams time to migrate at their own pace.

Use versioning for external APIs

If your system provides an HTTP API or similar to external clients, the safest route for major changes is to version the API. Introduce a v2 API endpoint for the refactored logic, keep v1 running (maybe internally calling v2 or using a translation layer). Clients can move to v2 at their own pace.

It’s extra work to maintain two APIs temporarily, but it prevents a breaking change from angering users or causing outages. Always communicate changes clearly and provide migration guides if applicable.

Have a clear deprecation policy

Make sure there’s a policy (and communication) around how long deprecated features will be supported. For internal APIs, maybe it’s one release cycle. For external ones, maybe multiple cycles or never removal without a major version bump. A good practice is to announce deprecation early.

If you’re exposing an HTTP API, consider introducing a new versioned endpoint (for example, /api/v2/send_email) and maintain the older /api/v1/send_email temporarily. Internally, v1 might call v2 with default parameters, ensuring behavior stays consistent for existing clients.

In summary, maintain backward compatibility whenever possible, and implement a clear deprecation policy for anything you do change.

Write adapter or compatibility layers

In some cases, you can write an adapter to bridge old and new systems. For instance, suppose you refactor the underlying data model of your application, but you still have old configuration files in the old format. Rather than forcing all those files to be rewritten immediately, you could write a small adapter that translates the old format to the new one at runtime (or during startup). This way, old data continues to work.

Test for compatibility

Include tests that specifically ensure backward compatibility. For instance, if you have a public API, keep a suite of tests using the old API contracts and run them against the refactored code, they should still pass.

In summary, ensure that as you refactor, the external behavior and contracts remain consistent. This careful approach protects your users and downstream systems, allowing you to reap the internal benefits of refactoring without causing external chaos.

5. Handling dependencies and tight coupling

One of the hairiest aspects of refactoring a large codebase is dealing with deeply interdependent code. Complex systems often suffer from tight coupling. Module A assumes details about Module B and vice versa, global variables or singletons are used all over, or a change in one place ripples through half the codebase.

Reducing coupling is a significant aim of refactoring because it makes the code more modular, meaning each piece can be understood, tested, and changed independently. So, how do we gradually loosen the coupling in a legacy system?

Let’s go over some strategies to reduce coupling.

Introduce interfaces or abstraction layers

A very effective way to decouple is to put an interface between components. For example, if you have a class that directly queries a database, introduce an interface and have the class use that instead. The underlying database code implements the interface.

# before: direct instantiation

class OrderService:

def __init__(self):

self.repo = OrderRepository()

# after: inject dependency

class OrderService:

def __init__(self, repo):

self.repo = repo

# wiring up in application startup

repo = OrderRepository(db_conn)

service = OrderService(repo)

Now, that class no longer depends on how the data is fetched. Applying the dependency inversion principle depends on abstractions, not concretions.

Use dependency injection

Once you have interfaces, use dependency injection to supply concrete implementations. Many frameworks support DI containers, or you can do it manually (passing in dependencies via constructors). Dependency injection means code A doesn’t instantiate code B itself – instead, B is passed into A.

This approach also makes unit testing easier (you can inject mock dependencies).

Facades or wrapper services

If a particular subsystem is heavily entangled with others, consider creating a Facade, an object that provides a simplified interface to a larger body of code. Other parts of the system are then called the Facade, not the many internal methods of the subsystem. Internally, the subsystem can be refactored (even split into smaller pieces) as long as the Facade’s outward interface remains consistent.

This is similar to how microservices work (other services don’t care how one service is implemented internally – they just call its API), but you can do it in-process, too.

Gradual replacement (Parallel Run)

If a specific component is to be replaced with a new implementation, it can help to run them in parallel for a while. For instance, if you have a spaghetti module that you want to redo correctly, you could leave the spaghetti code in place for legacy calls but start routing new calls to the new module.

The result is a codebase where changes in one area (hopefully) won’t unpredictably break another, a key property of a maintainable system.

6. Testing Strategies (Safely Refactoring with Confidence)

A robust testing strategy will give you the confidence to make sweeping changes because you’ll know quickly if something important breaks. Here’s how to approach testing in the context of a large refactoring:

Establish a baseline with regression tests

Before you even begin refactoring a particular component, make sure you have tests that cover its current behavior. You're lucky if the codebase already has a good test suite, but many legacy systems have inadequate tests.

One of the first tasks in those cases is often writing characterization tests. A characterization test is a test that documents what the system currently does, not what we think it should do.

As Feathers says, “a characterization test is a test that characterizes the actual behavior of a piece of code.” This allows you to take a snapshot of what it does and ensure that it doesn’t change.

This gives you a safety net so you can refactor with confidence that you’re not introducing regressions. Use automated test suites to help things run smoothly (unit, integration, end-to-end).

Continuous integration (CI)

It is highly recommended that testing be integrated into a CI pipeline that runs on every commit or merge. This way, you catch a bug during refactoring as soon as you introduce it, tightening the feedback loop.

Canary releases and feature flags

Beyond pre-release testing, consider strategies for safely deploying refactored code. A canary release involves rolling out the change to a small subset of users or servers first, observing it, and then gradually expanding.

This is great for catching issues that tests might miss (for example, performance issues or edge cases in production data). If the canary looks good (no errors, metrics are healthy), you proceed to full rollout. If not, you rollback quickly—with only a small impact scope.

Performance and load testing

If performance is a concern, incorporate performance tests into your strategy. This can be done in a staging environment. You might reconsider your approach or optimize the new code if you see a significant regression.

Testing legacy code lacking tests

If you’re dealing with a part of the system with zero tests (not uncommon in older code), prioritize getting at least some coverage there. There are also techniques like approval testing (where you generate output and have a human approve it as correct, then use that as a baseline for future tests). The key is not to refactor entirely in the dark; give yourself at least a flashlight in the form of tests!

In sum, a strong testing strategy is non-negotiable for refactoring complex systems. It’s your safety net, early warning system, and guide to know that your “cleanup” hasn’t broken anything vital.

7. Refactoring Without Breaking Performance

A common concern when refactoring is whether these cleaner code changes will make my system slower or more resource-hungry. Ideally, refactoring is about the internal structure and shouldn’t change external behavior, and performance is part of the behavior.

In theory, performance should remain the same if you don’t change algorithms or data structures in a way that affects complexity.

In practice, though, performance can be inadvertently affected by refactoring. The new code may be more readable but uses more memory, or perhaps a critical caching mechanism was removed in the spirit of simplicity.

Senior engineers need to be mindful of performance-sensitive parts of the system when refactoring and take steps to avoid regressions (or even improve performance where possible).

Here’s how to refactor with performance in mind:

Identify performance-critical code paths

Not all codes are equal regarding performance impact. If you refactor them, treat it almost like a functional change: you must re-measure performance afterwards. You have more leeway for parts of the code that run rarely or are not bottlenecks.

Use profiling before and after

A profiler is a tool that measures where time is spent in your code or how memory is allocated. It’s beneficial to run a profiler on the code before refactoring a module to see how it behaves, and then run it after to compare. If you see, for example, that after refactoring, a function now shows up as taking 30% of execution time (when it was negligible before), that’s a red flag. Maybe the new code calls it more times than before.

import cProfile, pstats

from mymodule import slow_function

def profile(fn):

profiler = cProfile.Profile()

profiler.enable()

fn()

profiler.disable()

stats = pstats.Stats(profiler).strip_dirs().sort_stats('cumtime')

stats.print_stats(10)

# run before refactor

profile(lambda: slow_function())

# after you refactor slow_function(), re-run and compare stats

When possible, improve performance through refactoring

On the flip side, refactoring can help performance.

For example, by refactoring duplicated code into one place, you can use better caching in that one place. So, watch for performance improvement opportunities that arise naturally as you refactor.

Performance should be treated as part of the “external behavior” that needs to be preserved in a good mindset. Refactoring should ideally not make things slower for users. To ensure that, incorporate performance checks into your plan, especially for critical sections. Measure, don’t guess. The end goal is a codebase that is both clean and fast enough.

8. Automate Code Reviews with AI tools

Refactoring code is an ongoing process, not a one-time event – AI code review tools help enforce clean-code standards, catch smells early, and reduce the repetitive tasks that can bog down human reviewers. This frees your engineers to focus on deeper architectural or domain-specific issues.

One powerful option is CodeRabbit, an AI-driven review platform designed to cut review time and bugs in half.

Here’s how it works and why it can boost your refactoring workflow:

AI-powered contextual feedback

CodeRabbit analyzes pull requests line by line, applying both advanced language models and static analysis under the hood. It flags potential bugs, best-practice deviations, and style issues before a human opens the PR.

Some other features include:

Auto-generated summaries and 1-click fixes – Summarize large PRs and apply straightforward fixes instantly.

Real-time collaboration and AI chat – Chat with the AI for clarifications, alternate code snippets, and instant feedback.

Integrates with popular dev platforms – Supports GitHub, GitLab, and Azure DevOps for seamless PR scanning.

CodeRabbit even has a free AI code reviews in VS Code and with this VS Code extension, you can get the most advanced AI code reviews directly in your code editor, saving review time, catching more bugs, and helping you in refactoring.

Summary

Refactoring a complex enterprise codebase is like renovating a large building while people still live in it without collapsing the structure.

Refactoring should be an ongoing process. You prevent the codebase from decaying by incorporating these practices into your regular development (perhaps allocating some time each sprint for refactoring or doing it opportunistically when touching your code). Each minor refactoring should not be too complex, and the cumulative effect is significant.

As Martin Fowler puts it, a series of small changes can lead to a significant improvement in design.

That's it for this blog. I hope you learned something new today.

If you want to read more interesting articles about developer tools, React, Next.js, AI and more, then I'll encourage you to checkout my blog.

Some of the new and interesting articles I've written in the last 24 months.

You can get in touch if you have any questions or corrections. I’m expecting them.

And if you found this blog useful, please share it with your friends and colleagues who might benefit from it as well. Your support enables me to continue producing useful content for the tech community.

Now it’s time to take the next step by subscribing to my newsletter and following me on Twitter.

![[The AI Show Episode 148]: Microsoft’s Quiet AI Layoffs, US Copyright Office’s Bombshell AI Guidance, 2025 State of Marketing AI Report, and OpenAI Codex](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20148%20cover%20%281%29.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 146]: Rise of “AI-First” Companies, AI Job Disruption, GPT-4o Update Gets Rolled Back, How Big Consulting Firms Use AI, and Meta AI App](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20146%20cover.png)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Alan_Wilson_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_pichetw_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Apple Leads Global Wireless Earbuds Market in Q1 2025 [Chart]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97394/97394/97394-640.jpg)

![OpenAI Acquires Jony Ive's 'io' to Build Next-Gen AI Devices [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97399/97399/97399-640.jpg)

![Apple Shares Teaser for 'Chief of War' Starring Jason Momoa [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97400/97400/97400-640.jpg)