Why Energy Star works so well—and why the private sector can’t replace it

To Deb Cloutier, president and founder of the sustainability firm RE Tech Advisors, the news that the Trump administration is planning to get rid of Energy Star simply didn’t make sense. Trump’s claims that he wants to reduce Americans’ energy bills is “completely at odds with this move to scrap the program that certifies energy efficient appliances. And she sees no viable way for private companies or nonprofits to fill this gap. She would know what it takes: Cloutier is one of the original designers of the program. Energy Star officially launched in 1992, under President George H. Bush. Cloutier helped shape the program’s focus on building efficiency, and then worked as a consultant every year since its launch. In the past 30 years, Energy Star has “exceeded all expectations,” Cloutier says: It saves consumers more than $40 billion every year on their bills, and helps certified buildings use 35% less energy, which means lower operating costs. Energy Star is voluntary, not mandatory Energy Star was specifically intended to be a voluntary, nonregulatory way of getting businesses to adopt and understand energy efficiency. The program doesn’t force businesses or building owners to participate. And yet more than 16,000 companies and organizations do—from appliance manufacturers to school districts. “Dozens of voluntary programs exist today, but Energy Star was the seminal first program that proved that businesses working in concert with government in a collaborative fashion could learn from one another, and develop resources that would not be brought to market by the businesses on their own,” Cloutier says. It has been a model for other public-private partnerships since, some even directly taking Energy Star’s tools: Canada uses Energy Star’s buildings portfolio manager for how it rates and ranks its own buildings. Businesses don’t often want to be the first to adopt something new like energy efficiency metrics; it’s a risk, and not always clear how the market will respond. But Energy Star was able to convene industry leaders together so multiple businesses could adopt these standards at once. Then, it started recognizing the top 25% most efficient products, buildings, and manufacturers. “It really helped spark that competitive nature of businesses to try and set goals to have X percent of their portfolio that has energy Star certification,” Cloutier says. An impartial agency, and a recognizable symbol Because Energy Star is a government program, it provides an impartial scoring metric for efficiency, based on rigorous scientific research. Energy Star’s iconic blue label is also easily recognizable by consumers: According to the program, nearly 90% of American households recognize the symbol. Without one symbol from a trusted, third-party source, manufacturers or retailers may put their own efficiency labels on products, which would make for a confusing and crowded landscape for consumers. It also wouldn’t be clear if those labels are consistent in what they measure or reward, or who’s verifying those claims. And if a nonprofit were to take over Energy Star’s role, it’s unlikely that it could cover the same array of industries—retail, manufacturing, residential, schools, and state and local governments—that the federal government does. “It would be a tall order to find something that replicates the federal government’s impartiality and breadth,” Cloutier says. Energy Star simplifies the efficiency process The federal government is in a unique position to have the national energy data, the research from national laboratories, and the industry expertise that underpin Energy Star’s tools and standards. The program draws from other government agencies like the Energy Information Administration, and it incorporates state and local regulations around emissions caps and what information buildings must disclose around their energy consumption. “If you own and operate buildings in more than one state or multinational jurisdictions, it’s already a very complex compliant landscape,” Cloutier says. But Energy Star helps simplify the process through things like its portfolio manager software tool, which allows entities to enter their buildings’ energy consumption and receive a score between 1 and 100, and to track their improvement over time. The private sector not only would struggle to access all the national energy data and laboratory research crucial for Energy Star, it would also face challenges from businesses themselves. “I think most entities would be hesitant to give what they would consider to be confidential business information around energy usage to a third party,” Cloutier says. Private businesses likely couldn’t carry out Energy Star at a large scale either. Its portfolio manager is used by more than 280,000 properties. For a private business to fund such an expansive, far-reaching tool, it would likely have to charge for it, Cloutier says—which would burden American

To Deb Cloutier, president and founder of the sustainability firm RE Tech Advisors, the news that the Trump administration is planning to get rid of Energy Star simply didn’t make sense. Trump’s claims that he wants to reduce Americans’ energy bills is “completely at odds with this move to scrap the program that certifies energy efficient appliances. And she sees no viable way for private companies or nonprofits to fill this gap. She would know what it takes: Cloutier is one of the original designers of the program.

Energy Star officially launched in 1992, under President George H. Bush. Cloutier helped shape the program’s focus on building efficiency, and then worked as a consultant every year since its launch. In the past 30 years, Energy Star has “exceeded all expectations,” Cloutier says: It saves consumers more than $40 billion every year on their bills, and helps certified buildings use 35% less energy, which means lower operating costs.

Energy Star is voluntary, not mandatory

Energy Star was specifically intended to be a voluntary, nonregulatory way of getting businesses to adopt and understand energy efficiency. The program doesn’t force businesses or building owners to participate. And yet more than 16,000 companies and organizations do—from appliance manufacturers to school districts.

“Dozens of voluntary programs exist today, but Energy Star was the seminal first program that proved that businesses working in concert with government in a collaborative fashion could learn from one another, and develop resources that would not be brought to market by the businesses on their own,” Cloutier says. It has been a model for other public-private partnerships since, some even directly taking Energy Star’s tools: Canada uses Energy Star’s buildings portfolio manager for how it rates and ranks its own buildings.

Businesses don’t often want to be the first to adopt something new like energy efficiency metrics; it’s a risk, and not always clear how the market will respond. But Energy Star was able to convene industry leaders together so multiple businesses could adopt these standards at once. Then, it started recognizing the top 25% most efficient products, buildings, and manufacturers. “It really helped spark that competitive nature of businesses to try and set goals to have X percent of their portfolio that has energy Star certification,” Cloutier says.

An impartial agency, and a recognizable symbol

Because Energy Star is a government program, it provides an impartial scoring metric for efficiency, based on rigorous scientific research. Energy Star’s iconic blue label is also easily recognizable by consumers: According to the program, nearly 90% of American households recognize the symbol.

Without one symbol from a trusted, third-party source, manufacturers or retailers may put their own efficiency labels on products, which would make for a confusing and crowded landscape for consumers. It also wouldn’t be clear if those labels are consistent in what they measure or reward, or who’s verifying those claims.

And if a nonprofit were to take over Energy Star’s role, it’s unlikely that it could cover the same array of industries—retail, manufacturing, residential, schools, and state and local governments—that the federal government does. “It would be a tall order to find something that replicates the federal government’s impartiality and breadth,” Cloutier says.

Energy Star simplifies the efficiency process

The federal government is in a unique position to have the national energy data, the research from national laboratories, and the industry expertise that underpin Energy Star’s tools and standards. The program draws from other government agencies like the Energy Information Administration, and it incorporates state and local regulations around emissions caps and what information buildings must disclose around their energy consumption.

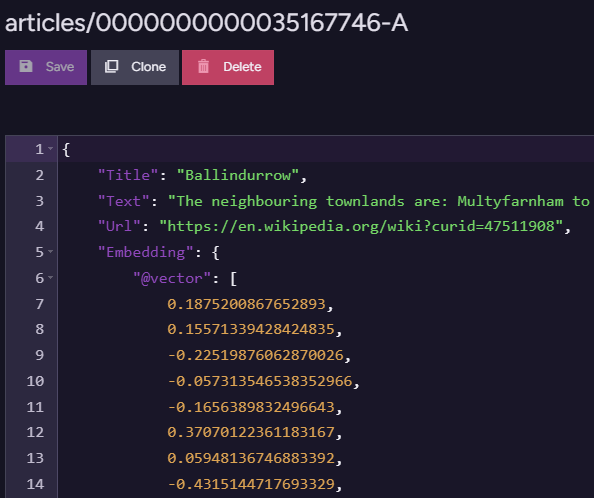

“If you own and operate buildings in more than one state or multinational jurisdictions, it’s already a very complex compliant landscape,” Cloutier says. But Energy Star helps simplify the process through things like its portfolio manager software tool, which allows entities to enter their buildings’ energy consumption and receive a score between 1 and 100, and to track their improvement over time.

The private sector not only would struggle to access all the national energy data and laboratory research crucial for Energy Star, it would also face challenges from businesses themselves. “I think most entities would be hesitant to give what they would consider to be confidential business information around energy usage to a third party,” Cloutier says.

Private businesses likely couldn’t carry out Energy Star at a large scale either. Its portfolio manager is used by more than 280,000 properties. For a private business to fund such an expansive, far-reaching tool, it would likely have to charge for it, Cloutier says—which would burden American businesses, buildings, and families directly.

As a government program, Energy Star is incredibly cost-effective: For every federal dollar invested, it delivers a return of $350. “When you look at the very small budget to run Energy Star, I would say it’s sort of the little engine that could in terms of its results,” she says. The program supports more than 750,000 U.S. jobs, and Americans purchase 300 million Energy Star-certified products a year, worth $100 billion in market value.

Energy efficiency benefits everyone

Energy Star has long had bipartisan support, and for good reason. Making products and buildings more efficient helps the entire country—not only by lowering people’s energy bills, but by putting less pressure on the national energy grid. That means less blackouts and brownouts, too. “The more we can help drive down the amount of energy used to live, work, and play in buildings, that helps produce more bandwidth on the grid,” Cloutier says. U.S. energy demand is only growing, especially with more data centers to support AI and cloud services, which will also likely raise energy prices for consumers.

Without Energy Star, Americans might be more likely to choose the cheapest option at the appliance store, not realizing that doing so will actually increase their energy bills over time. It’s not easy, without a third-party label like Energy Star, to translate that trade-off in purchase price versus long-term savings. But by having the Energy Star product, consumers know that item inherently saves energy; Energy Star also details the annual energy use of a product—and how much that use compares to the federal standard. Consumers can even search for items like dishwashers and the Energy Star website will sort them by energy use.

Losing Energy Star also means buildings might lag on efficiency, in part because the process to meet efficiency standards and implement energy-saving tools will be a more difficult undertaking. Building operators may then pass those increased utility costs on to residents, in the case of apartment buildings, or customers, in the case of hotels. Cloutier has seen numerous examples of how aligning with Energy Star standards has helped building operators save money; thousands of school districts, she says, have saved on operating costs that can then make more resources available for teachers.

And Energy Star is authorized by Congress, which means it can’t legally be ended in this fiscal year. What happens after that isn’t clear, but Energy Star’s benefits are. During his first term, Trump tried to end the program but faced strong opposition, and Energy Star survived. “I am highly encouraging our clients and peers in the industry,” Cloutier says, “. . . to defend the value of Energy Star again.”

![[The AI Show Episode 146]: Rise of “AI-First” Companies, AI Job Disruption, GPT-4o Update Gets Rolled Back, How Big Consulting Firms Use AI, and Meta AI App](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20146%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The ChatGPT & AI Super Bundle (91% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![How to make Developer Friends When You Don't Live in Silicon Valley, with Iraqi Engineer Code;Life [Podcast #172]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1747360508340/f07040cd-3eeb-443c-b4fb-370f6a4a14da.png?#)

![A rare look inside the TSMC Arizona plant making chips for Apple [Video]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/05/A-look-inside-the-TSMC-Arizona-plant-making-chips-for-Apple.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Why Apple Still Can't Catch Up in AI and What It's Doing About It [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97352/97352/97352-640.jpg)

![Sonos Move 2 On Sale for 25% Off [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97355/97355/97355-640.jpg)

![Apple May Not Update AirPods Until 2026, Lighter AirPods Max Coming in 2027 [Kuo]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97350/97350/97350-640.jpg)