‘They got rid of some of our best talent’: How Trump is hacking away at America’s cyber defenses

“We’ve had many, many threats against our nation,” President Trump said in the Oval Office in November 2018, as he announced the creation of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Now “we’re putting people that are the best in the world in charge,” he said, “and I think we’re going to have a whole different ball game.” Eight years later, his second administration is ripping up parts of the country’s cyber playbook and taking many of its best players off the field, from threat hunters and election defenders at CISA to the leader of the NSA and Cyber Command. Amid a barrage of severe attacks like Volt Typhoon and rising trade tensions, lawmakers, former officials, and cyber professionals say that sweeping and confusing cuts are making the country more vulnerable and emboldening its adversaries. “There are intrusions happening now that we either will never know about or won’t see for years because our adversaries are undoubtedly stepping up their activity, and we have a shrinking, distracted workforce,” says Jeff Greene, a cybersecurity expert who has held top roles at CISA and the White House. The dismissals and budget cuts have eliminated hundreds of workers and jeopardized dozens of initiatives that help protect machines, networks, and individuals across the U.S. Most of the cuts are at CISA, which sits under the Department of Homeland Security and partners with the public and private sectors to defend grids, banks, networks, and other critical industries. It’s also responsible for protecting elections from hackers and foreign influence campaigns, efforts the President and Republicans have long accused of political censorship. Around 400 positions at the Dept. of Homeland Security have been cut so far, and in total, 1,300 jobs could be cut at CISA, or over a third of the agency’s workforce. Some of the earliest cuts hit contractors and probationary employees at CISA, eliminating an elite slate of experts recently hired through a new program geared toward attracting more talent from the private sector. (After a judge ordered the probationary workers to be rehired, the agency immediately placed them on administrative leave.) “They got rid of some of our best cyber talent,” says another veteran federal cyber official, speaking anonymously to avoid retribution. “It’s fucking ridiculous.” Many anticipated CISA would face heavy scrutiny under Trump 2.0, especially for its election security work. During her confirmation hearing, DHS chief Kristi Noem said the agency had gone “off-mission” with its work on elections and disinformation, and that she intends to make CISA “smaller and more nimble.” (Project 2025 called for closing the agency and moving what remains to the Dept. of Transportation.) But the cuts at CISA have extended to programs beyond election integrity, impacting much of what sits outside of the agency’s most basic mission of protecting .gov networks. More broadly, the cuts align with a February executive order that seeks to delegate the bulk of responsibility for disaster preparedness and response, “including cyber attacks, wildfires, hurricanes, and space weather,” to state and local governments. At the same time, the cuts are targeting programs that help cash-strapped states, small businesses and infrastructure operators defend their growing networks. The White House has cut resources around a key cybersecurity grant program that states have been clamoring for, and curtailed support for threat-advisory groups that assist states with network vulnerabilities, critical infrastructure, and election security. State and local cyber officials are worried the cuts will impact their ongoing efforts to fend off cyberattacks. According to a report published Tuesday by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, some government agencies say they will be unable to sustain their cybersecurity initiatives without the federal funding, which is up for reauthorization by Congress this year. “While I can understand [shifting more responsibility to states] in theory, it is a little concerning because we don’t really know what the plan is,” says Alex Whitaker, director of government affairs for the National Association of State Chief Information Officers. “States and localities are already on the front lines, and these are services they rely on.” Also shut down are CISA’s advisory boards focused on safety, AI, and telecommunications, which were conducting investigations into the China-linked hacking group Salt Typhoon and other ongoing threats. These were abruptly disbanded as part of an effort “ensuring that DHS activities prioritize our national security,” as an administrator wrote in an internal memo. Last week, two senior CISA officials who were leading its “Secure by Design” effort—aimed at making security core to the way our software is built—left the agency, adding to a number of other departures, and putting the initiative in jeopardy. “We’re

“We’ve had many, many threats against our nation,” President Trump said in the Oval Office in November 2018, as he announced the creation of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Now “we’re putting people that are the best in the world in charge,” he said, “and I think we’re going to have a whole different ball game.”

Eight years later, his second administration is ripping up parts of the country’s cyber playbook and taking many of its best players off the field, from threat hunters and election defenders at CISA to the leader of the NSA and Cyber Command. Amid a barrage of severe attacks like Volt Typhoon and rising trade tensions, lawmakers, former officials, and cyber professionals say that sweeping and confusing cuts are making the country more vulnerable and emboldening its adversaries.

“There are intrusions happening now that we either will never know about or won’t see for years because our adversaries are undoubtedly stepping up their activity, and we have a shrinking, distracted workforce,” says Jeff Greene, a cybersecurity expert who has held top roles at CISA and the White House.

The dismissals and budget cuts have eliminated hundreds of workers and jeopardized dozens of initiatives that help protect machines, networks, and individuals across the U.S. Most of the cuts are at CISA, which sits under the Department of Homeland Security and partners with the public and private sectors to defend grids, banks, networks, and other critical industries. It’s also responsible for protecting elections from hackers and foreign influence campaigns, efforts the President and Republicans have long accused of political censorship.

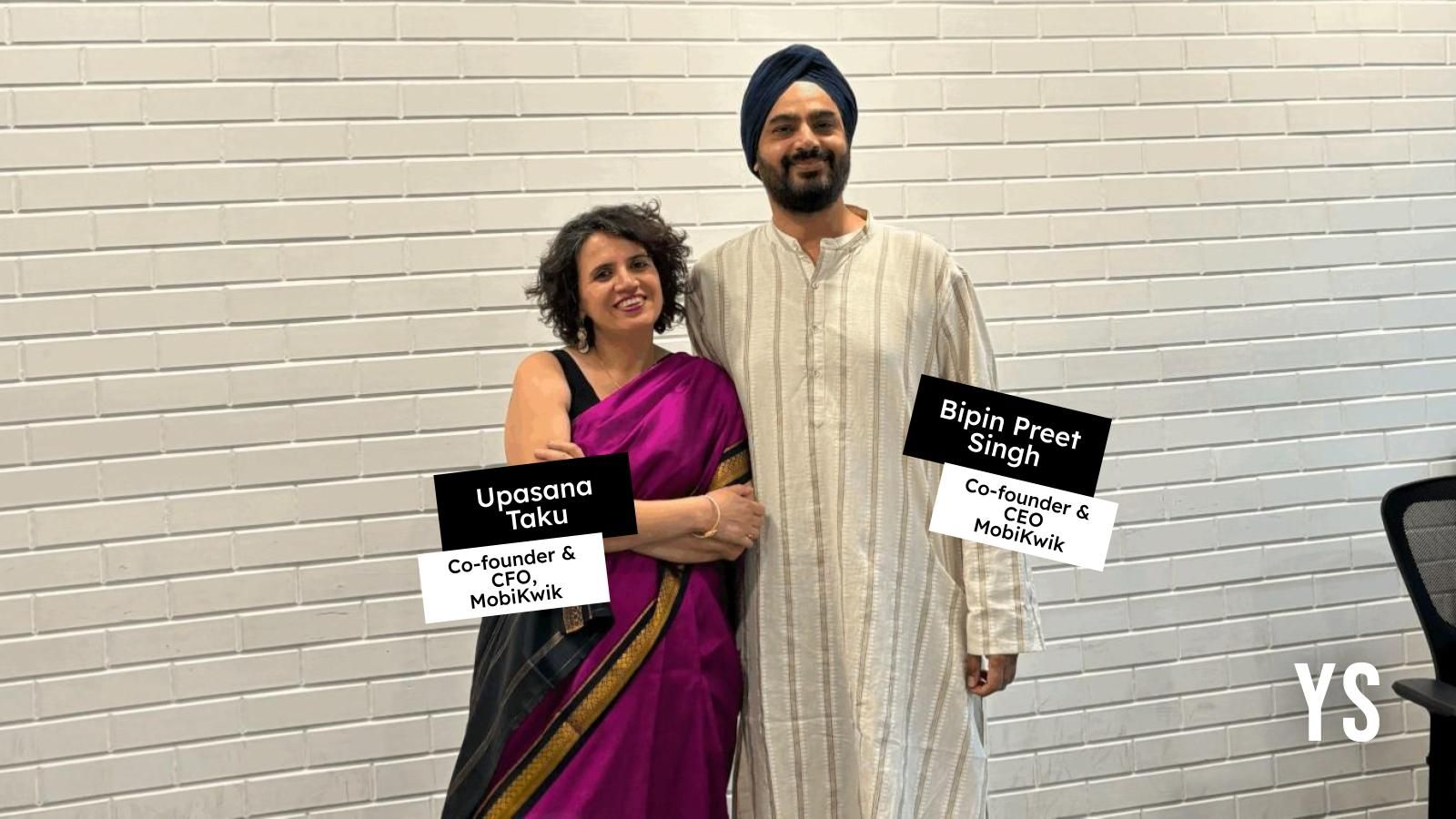

Around 400 positions at the Dept. of Homeland Security have been cut so far, and in total, 1,300 jobs could be cut at CISA, or over a third of the agency’s workforce. Some of the earliest cuts hit contractors and probationary employees at CISA, eliminating an elite slate of experts recently hired through a new program geared toward attracting more talent from the private sector. (After a judge ordered the probationary workers to be rehired, the agency immediately placed them on administrative leave.)

“They got rid of some of our best cyber talent,” says another veteran federal cyber official, speaking anonymously to avoid retribution. “It’s fucking ridiculous.”

Many anticipated CISA would face heavy scrutiny under Trump 2.0, especially for its election security work. During her confirmation hearing, DHS chief Kristi Noem said the agency had gone “off-mission” with its work on elections and disinformation, and that she intends to make CISA “smaller and more nimble.” (Project 2025 called for closing the agency and moving what remains to the Dept. of Transportation.)

But the cuts at CISA have extended to programs beyond election integrity, impacting much of what sits outside of the agency’s most basic mission of protecting .gov networks. More broadly, the cuts align with a February executive order that seeks to delegate the bulk of responsibility for disaster preparedness and response, “including cyber attacks, wildfires, hurricanes, and space weather,” to state and local governments.

At the same time, the cuts are targeting programs that help cash-strapped states, small businesses and infrastructure operators defend their growing networks. The White House has cut resources around a key cybersecurity grant program that states have been clamoring for, and curtailed support for threat-advisory groups that assist states with network vulnerabilities, critical infrastructure, and election security.

State and local cyber officials are worried the cuts will impact their ongoing efforts to fend off cyberattacks. According to a report published Tuesday by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, some government agencies say they will be unable to sustain their cybersecurity initiatives without the federal funding, which is up for reauthorization by Congress this year.

“While I can understand [shifting more responsibility to states] in theory, it is a little concerning because we don’t really know what the plan is,” says Alex Whitaker, director of government affairs for the National Association of State Chief Information Officers. “States and localities are already on the front lines, and these are services they rely on.”

Also shut down are CISA’s advisory boards focused on safety, AI, and telecommunications, which were conducting investigations into the China-linked hacking group Salt Typhoon and other ongoing threats. These were abruptly disbanded as part of an effort “ensuring that DHS activities prioritize our national security,” as an administrator wrote in an internal memo.

Last week, two senior CISA officials who were leading its “Secure by Design” effort—aimed at making security core to the way our software is built—left the agency, adding to a number of other departures, and putting the initiative in jeopardy.

“We’re undoing a lot of really good work that frankly was started under Trump 1,” says a former federal cyber official.

Enter revenge politics

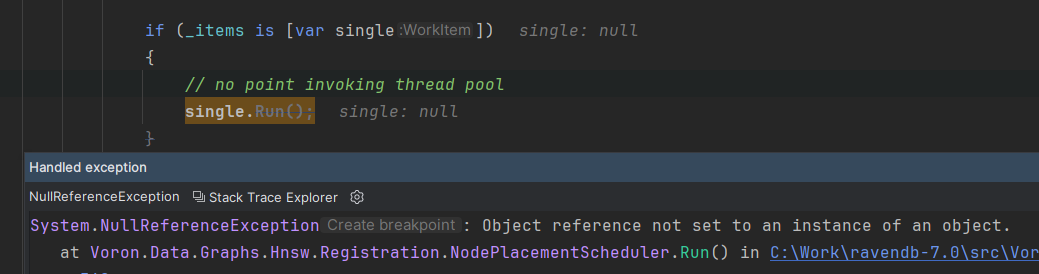

Amid the wave of efficiency-related cuts to cybersecurity, other decisions have cast a partisan shadow over a set of threats that are stubbornly indifferent to politics.

In an April 9 memo, Trump called for an investigation into CISA’s founding director, Chris Krebs, who earned the president’s ire in 2020 when he declared that the election was secure. The memo also demanded “a comprehensive evaluation of all of CISA’s activities over the last 6 years.”

On Monday, a public statement signed by hundreds of prominent cybersecurity professionals and academics condemned what they described as political retaliation. “Chris did the best he could in a difficult time, and he deserves our thanks not our anger,” says Greene.

“Right now, to see what’s happening to the cybersecurity community inside the federal government, we should be outraged,” Krebs, a lifelong Republican, said at the RSA Conference this week. “Absolutely outraged.”

Earlier in the month, Trump shocked the national security world when he abruptly fired Gen. Timothy Haugh, director of the National Security Agency and Cyber Command, and reassigned his deputy, without explanation. Some experts speculated the move could be part of a larger plan to split the leadership of NSA and Cyber Command, which are responsible for intelligence and military missions respectively. The right-wing influencer Laura Loomer, who visited the White House the day before, said the dismissals were related to questions about “loyalty.”

“Russia and China are laughing at us because we just fired the absolute best leaders,” Rep. Don Bacon, R-Nebraska, a member of the Armed Services Committee, told Face the Nation.

The firing of Gen. Haugh—an experienced four-star general with decades of experience in cyberspace—“really caught me off-guard,” one former CISA official says. “Those things have a morale impact that’s really hard to quantify.”

CISA, too, lacks a permanent leader. This month Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore, announced he was blocking the confirmation of Trump’s nominee to lead the agency, Sean Plankey, a veteran of the Pentagon and DHS, over CISA’s years-long refusal to release information regarding a vulnerability in global telecom networks.

In a statement, Wyden, a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, blamed the White House for weakening CISA and the country’s defenses. “Trump is kneecapping our country’s ability to defend itself against cyberattacks by disarming our country’s cybersecurity defenses and purging experienced professionals,” he said.

“From firing General Haugh, disbanding the Cyber Safety Review Board and preparing to slash the cybersecurity workforce at CISA, Trump is rolling out a digital red carpet to hackers from China and other adversary nations,” he added.

Some of the cyber decisions may reflect a push by Trump White House cyber officials toward a more offensive, deterrent posture. But former officials have worried the strategy could come at the expense of defense, and that its emphasis appears to be focused more heavily on China than on Russia.

One signal came in early March, when the Defense Secretary ordered Gen. Haugh at Cyber Command to temporarily pause offensive operations against Russia, amid negotiations with the Kremlin over Ukraine, as The Record and other outlets reported. Some experts at CISA were also directed to focus on adversaries other than Russia, sources told the Washington Post. The Pentagon later denied it had halted its cyber operations, according to Bloomberg, but the reports still chilled security experts, who say Russia remains a major cyberthreat to the U.S.

“If we’re dialing it back on hacking Russia, I think we have a high likelihood of seeing ransomware incidents go up against American companies and everybody else,” says one former White House cyber official.

In response to questions about specific cuts and the country’s cyber posture, a CISA spokesperson says in an email that the agency “was designed to work across public and private sectors to improve the nation’s cybersecurity, which demands more agility, flexibility, and innovation than traditional government organizations have allowed.”

“CISA continuously evaluates how we work with partners and takes decisive action to maximize impact while being good stewards of taxpayer dollars and aligning with Administration priorities and our authorities,” they added.

One Trump White House official, U.S. chief information officer Greg Barbaccia, struck a rare note of caution last month, when he urged federal agencies to refrain from laying off cybersecurity teams as they raced to complete mass layoffs.

“We believe cybersecurity is national security and we encourage Department-level Chief Information Officers to consider this when reviewing their organizations,” he wrote in an email to IT employees across the federal government.

Even CISA’s defenders acknowledge bureaucratic inefficiencies that hamper cyber defense. But they say Trump’s cuts are reckless and tainted by politics. Apart from upsetting cyber readiness, the upheaval and anxiety inside CISA could make it harder for the government to attract and retain top cyber talent, especially amid a severe talent shortage.

“It’s not good for bringing the best and the brightest into government, if you’re creating this environment of fear,” says the former White House official.

“People that we know will only respond to us on personal Signal, and they won’t even talk to anybody outside of government, because they’re so terrified of what the Trump people are doing,” they added.

The administration’s handling of sensitive data has raised a separate set of cyber alarms. Even before Signalgate and a slew of personal phones exposed military plans, the Department of Government Efficiency’s (DOGE) handling of government data, including on millions of Americans, prompted a slew of lawsuits. Meanwhile, one of two DOGE employees detailed to CISA is Edward Coristine, a college student who has been linked with a cybercrime gang and was suspected by an employer, cybersecurity firm Path Network, of leaking proprietary information to a competitor. Coristine did not respond to a request for comment.

‘Very concerning’ at the local level

For years, CISA has offered free services and consultations to states and municipalities that struggle to hire their own IT and cyber experts. State and local governments, K-12 schools, and critical infrastructure facilities are often short on resources and have limited tolerance for downtime, making them a top target for cyberattackers. Officials from every party have also expressed gratitude for CISA’s help protecting elections, adopted the agency’s recommendations, and sought out its services.

“Your IT person is a city council member; he or she is mowing the lawn and they’re also doing all the IT stuff,” says Whitaker. “There’s never enough resources.”

But soon, layoffs are expected to decimate the units at CISA primarily responsible for much of this work.

Cuts are expected at the Integrated Operations Division, which coordinates CISA operations at the regional level and helps respond to incidents that impact critical infrastructure, and at the Stakeholder Engagement Division, which helps coordinate national and global information sharing and helps local governments, companies, and other organizations protect critical infrastructure. The National Risk Management Center (NRMC), which coordinates risk analysis for cyber and critical infrastructure, is also expected to see significant cuts.

In March the administration also eliminated an inter-state threat-advisory organization focused on election threats, and placed on leave dozens of personnel who work on combating foreign election disinformation. At the FBI, Attorney General Pam Bondi also dissolved a task force focused on foreign influence around U.S. elections. And the State Department has put dozens of employees who tracked global disinformation on leave, closing the operation that had publicized the spread of Chinese and Russian propaganda.

Cuts have also impacted a separate threat sharing program, the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC). Some of its work will continue, including support for an intrusion detection system geared toward government networks. But other services have been decimated, including stakeholder engagement, cyber threat intelligence, and cyber incident response.

Cuts to the MS-ISAC are “very concerning,” Whitaker says. MS-ISAC is considered “one of the best tools that states have to figure out where the threats are coming from.”

The New York-based nonprofit that runs the program has said it will continue its efforts with more limited funding in the short-term. The group recently issued two advisories about vulnerabilities and patches, which was the first time it had done so in more than a month.

States also stand to lose millions in vital cyber funds. In 2021, Congress created a four-year, $1 billion cybersecurity grant program for state and local governments. Since then, every state but one has taken advantage of the funds to back initiatives like deploying intrusion-monitoring software, securing websites, and teaching cyber hygiene, with states required to direct at least 80% of their grant awards to cash-strapped local governments.

In Connecticut in 2022, more than 100 communities requested a combined $12 million, far more than the state’s $2.7 million allotment from Washington, its CIO told the House Subcommittee on Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection at a March hearing.

“The federal funding is not big,” says Whitaker, “but it’s essential.”

The grant program expires next September, however, leaving its fate in the hands of a GOP-controlled Congress, and Kristi Noem, whose state was the only one in the country not to take the federal cyber funds.

And the funding is already in jeopardy. The White House recently cut staff at CISA and FEMA who manage the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, and an Office of Management and Budget memo that went into effect in January directs federal agencies to “temporarily pause all activities related to obligations or disbursement of all Federal financial assistance,” including dozens of cybersecurity-specific federal grant programs and other federal grants that can help bolster cyber defenses. A federal judge temporarily halted the order the same day.

The prospect of state governments shouldering more responsibility for cybersecurity has rattled some state officials, who operate on often razor-thin budgets, and are already eyeing cuts to technical and fiscal support.

”States have tools, but states need the federal government to lead on coordination, unification and major incident response,” adds Colin Ahern, the chief cyber officer for New York State. “We think that one of the things that only the feds can really do is this information sharing and operational collaboration.”

A retreat by Washington is also prompting companies to reevaluate their own defenses, according to Danny Rogers, CEO of iVerify, which partnered with CISA last year on a security toolkit for communities at higher risk of cyberattack.

The cuts, he said, suggest “that you’re really not going to be able to rely on the government to have your back anymore.”

The effects won’t be immediately evident. “It’s a boil the frog thing,” he added, “where we’re going to wake up one day and realize there’s a lot more catastrophe and a lot less capacity to deal with it.”

Contact Alex at apasternack@fastcompany.com or on Signal at alex.265

![[Free Webinar] Guide to Securing Your Entire Identity Lifecycle Against AI-Powered Threats](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjqbZf4bsDp6ei3fmQ8swm7GB5XoRrhZSFE7ZNhRLFO49KlmdgpIDCZWMSv7rydpEShIrNb9crnH5p6mFZbURzO5HC9I4RlzJazBBw5aHOTmI38sqiZIWPldRqut4bTgegipjOk5VgktVOwCKF_ncLeBX-pMTO_GMVMfbzZbf8eAj21V04y_NiOaSApGkM/s1600/webinar-play.jpg?#)

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![Google Home app fixes bug that repeatedly asked to ‘Set up Nest Cam features’ for Nest Hub Max [U]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2022/08/youtube-premium-music-nest-hub-max.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![New Hands-On iPhone 17 Dummy Video Shows Off Ultra-Thin Air Model, Updated Pro Designs [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97171/97171/97171-640.jpg)

![Apple Shares Trailer for First Immersive Feature Film 'Bono: Stories of Surrender' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97168/97168/97168-640.jpg)