Is AI “normal”?

Right now, despite its ubiquity, AI is seen as anything but a normal technology. There is talk of AI systems that will soon merit the term “superintelligence,” and the former CEO of Google recently suggested we control AI models the way we control uranium and other nuclear weapons materials. Anthropic is dedicating time and money…

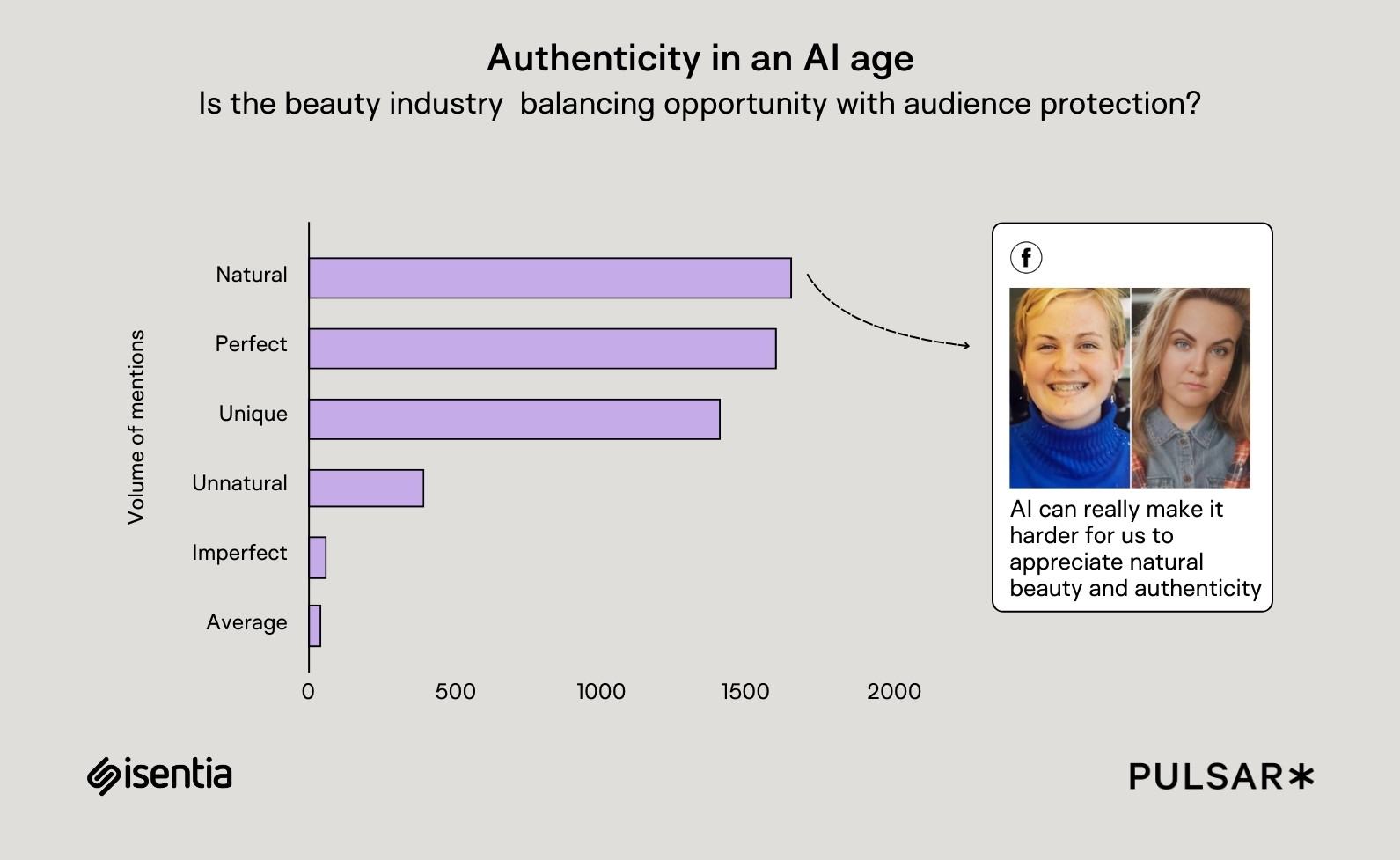

Right now, despite its ubiquity, AI is seen as anything but a normal technology. There is talk of AI systems that will soon merit the term “superintelligence,” and the former CEO of Google recently suggested we control AI models the way we control uranium and other nuclear weapons materials. Anthropic is dedicating time and money to study AI “welfare,” including what rights AI models may be entitled to. Meanwhile, such models are moving into disciplines that feel distinctly human, from making music to providing therapy.

No wonder that anyone pondering AI’s future tends to fall into either a utopian or a dystopian camp. While OpenAI’s Sam Altman muses that AI’s impact will feel more like the Renaissance than the Industrial Revolution, over half of Americans are more concerned than excited about AI’s future. (That half includes a few friends of mine, who at a party recently speculated whether AI-resistant communities might emerge—modern-day Mennonites, carving out spaces where AI is limited by choice, not necessity.)

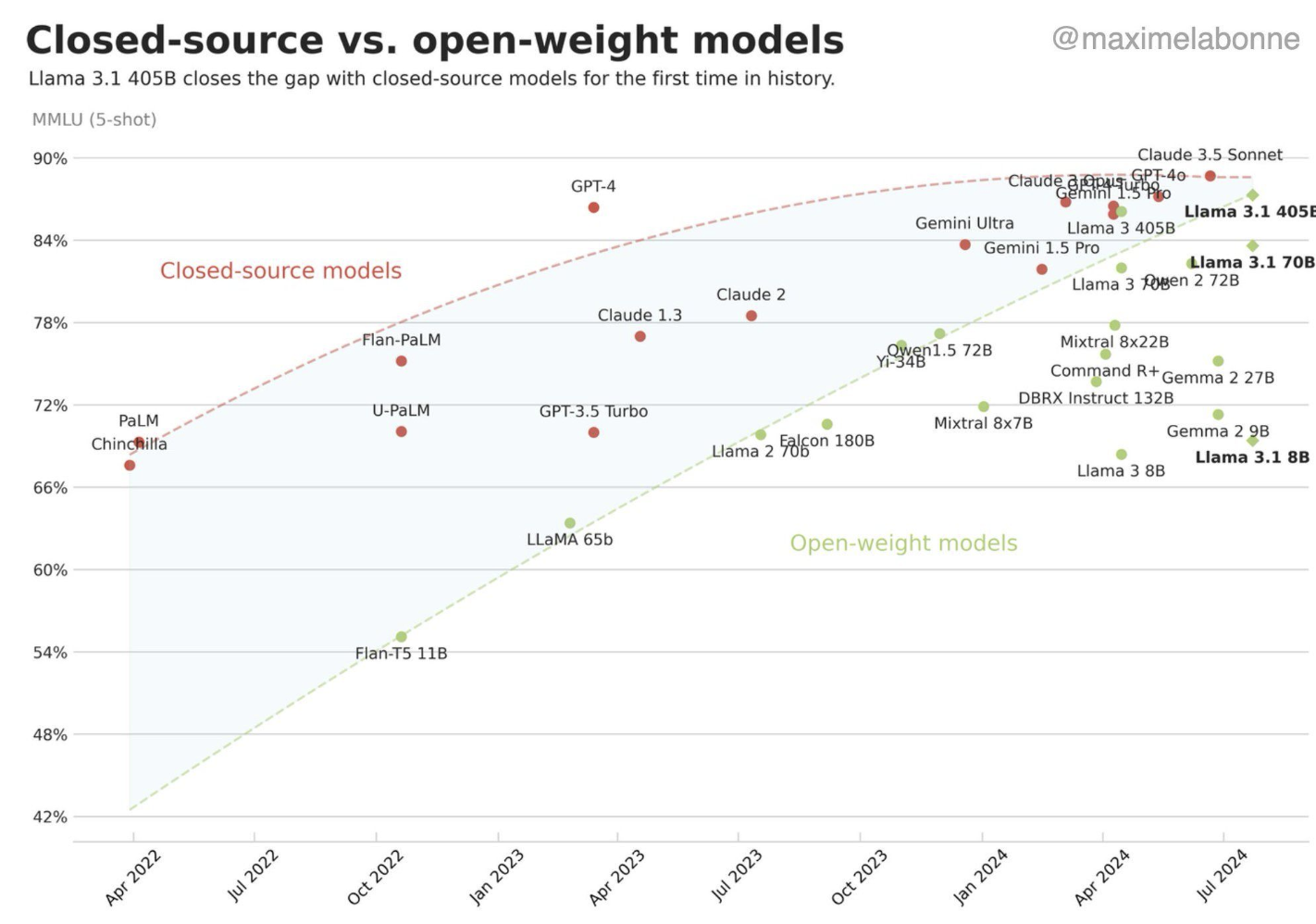

So against this backdrop, a recent essay by two AI researchers at Princeton felt quite provocative. Arvind Narayanan, who directs the university’s Center for Information Technology Policy, and doctoral candidate Sayash Kapoor wrote a 40-page plea for everyone to calm down and think of AI as a normal technology. This runs opposite to the “common tendency to treat it akin to a separate species, a highly autonomous, potentially superintelligent entity.”

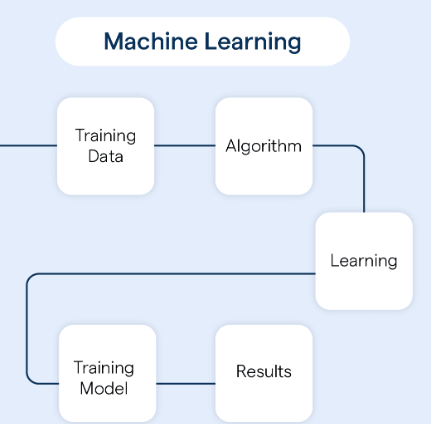

Instead, according to the researchers, AI is a general-purpose technology whose application might be better compared to the drawn-out adoption of electricity or the internet than to nuclear weapons—though they concede this is in some ways a flawed analogy.

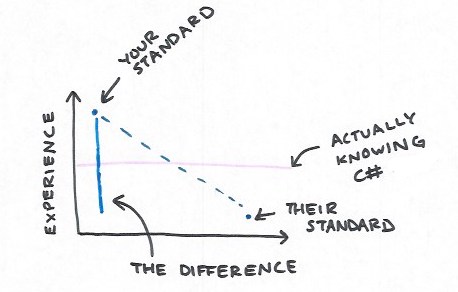

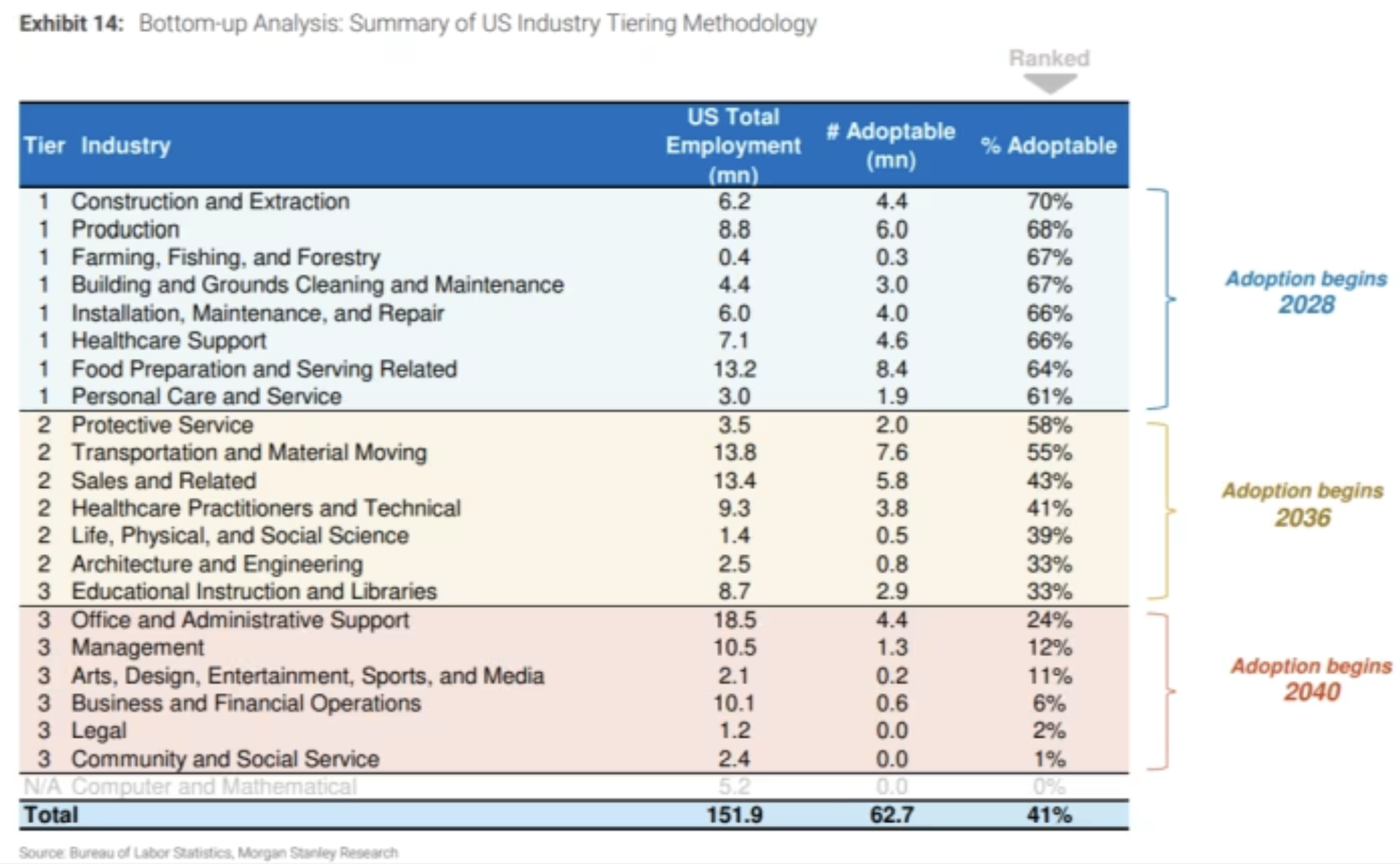

The core point, Kapoor says, is that we need to start differentiating between the rapid development of AI methods—the flashy and impressive displays of what AI can do in the lab—and what comes from the actual applications of AI, which in historical examples of other technologies lag behind by decades.

“Much of the discussion of AI’s societal impacts ignores this process of adoption,” Kapoor told me, “and expects societal impacts to occur at the speed of technological development.” In other words, the adoption of useful artificial intelligence, in his view, will be less of a tsunami and more of a trickle.

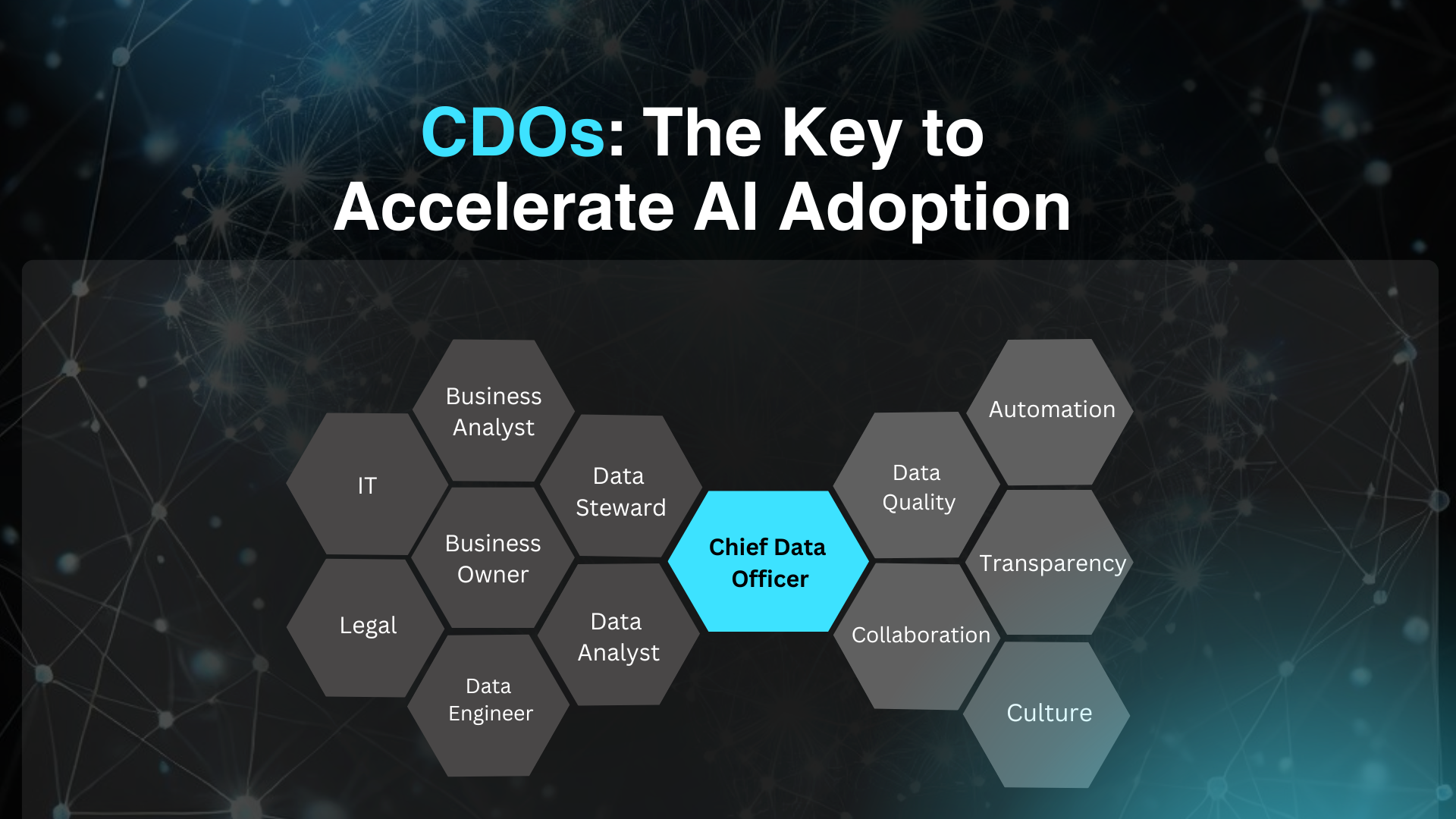

In the essay, the pair make some other bracing arguments: terms like “superintelligence” are so incoherent and speculative that we shouldn’t use them; AI won’t automate everything but will birth a category of human labor that monitors, verifies, and supervises AI; and we should focus more on AI’s likelihood to worsen current problems in society than the possibility of it creating new ones.

“AI supercharges capitalism,” Narayanan says. It has the capacity to either help or hurt inequality, labor markets, the free press, and democratic backsliding, depending on how it’s deployed, he says.

There’s one alarming deployment of AI that the authors leave out, though: the use of AI by militaries. That, of course, is picking up rapidly, raising alarms that life and death decisions are increasingly being aided by AI. The authors exclude that use from their essay because it’s hard to analyze without access to classified information, but they say their research on the subject is forthcoming.

One of the biggest implications of treating AI as “normal” is that it would upend the position that both the Biden administration and now the Trump White House have taken: Building the best AI is a national security priority, and the federal government should take a range of actions—limiting what chips can be exported to China, dedicating more energy to data centers—to make that happen. In their paper, the two authors refer to US-China “AI arms race” rhetoric as “shrill.”

“The arms race framing verges on absurd,” Narayanan says. The knowledge it takes to build powerful AI models spreads quickly and is already being undertaken by researchers around the world, he says, and “it is not feasible to keep secrets at that scale.”

So what policies do the authors propose? Rather than planning around sci-fi fears, Kapoor talks about “strengthening democratic institutions, increasing technical expertise in government, improving AI literacy, and incentivizing defenders to adopt AI.”

By contrast to policies aimed at controlling AI superintelligence or winning the arms race, these recommendations sound totally boring. And that’s kind of the point.

This story originally appeared in The Algorithm, our weekly newsletter on AI. To get stories like this in your inbox first, sign up here.

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Muhammad_R._Fakhrurrozi_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![AirPods Pro 2 With USB-C Back On Sale for Just $169! [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96315/96315/96315-640.jpg)

![Apple Releases iOS 18.5 Beta 4 and iPadOS 18.5 Beta 4 [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97145/97145/97145-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds watchOS 11.5 Beta 4 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97147/97147/97147-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds visionOS 2.5 Beta 4 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97150/97150/97150-640.jpg)