I love finite-state machines:)

Hi, my name is Anton. I'm a software developer specializing in cross-platform mobile development, currently working at a fintech company where I help build a neo-banking application. There's often debate about design patterns—do we really need them, or are they just outdated theory with little practical value in modern software development? I strongly disagree with the idea that patterns are unnecessary. In my view, having a solid foundation in theoretical concepts is extremely valuable. It's like recursion: you might not need it every day, but when you encounter a problem that is recursive in nature—like traversing a file system—you simply can't solve it effectively any other way. The same applies to design patterns. Some processes naturally fit certain patterns, and recognizing them allows you to solve problems in a well-known, structured way. Otherwise, you risk reinventing the wheel—often with a much, much less effective result. Recently, I was assigned an interesting task at work that proves my point, and I think it's worth sharing. In my daily work, I'm always looking for patterns that can help implement features more cleanly and maintainably. Since I mostly work on the client side, which is inherently stateful, one of my favorite patterns is the finite-state machine. Even if you know nothing about state machines, you're probably using them unconsciously in your code. The reason is that state machines are incredibly common in our daily lives - they appear in everything from traffic lights and vending machines to smartphone apps and ATMs. Any system that moves through specific states in response to certain inputs or events is essentially a state machine. We interact with them constantly, often without realizing it. But if you use them unconsciously, they usually end up as a messy combination of boolean flags and if statements. It's hard to add new states, and each additional state makes the abstraction worse and worse. It's much better if you can recognize the pattern and organize it properly. That's exactly the situation we had. My team and I are pretty obsessed with code quality. During a regular upgrade of our dependencies (a routine process in any React Native app), we decided to migrate to the latest version of React Navigation, and as part of that process, refactor some connected features. While investigating what to improve, the identity verification process caught our attention. Like in any banking app, a crucial part of ours is verifying customer identity and documents during onboarding. This is a fairly complex process, involving many steps, and in our app, it was spread across nine screens. And the original implementation, to be honest, was far from ideal. It seemed like previously nobody had tried to see the whole picture. Each screen was treated as a separate entity, and as a result, the logic for each step was spread throughout the functional component body—often 50 to 150 lines of business logic per screen, right in the render method. The communication between screens was also poor. All data was passed through route params, which is fine for primitive values but becomes unwieldy for complex objects used across multiple screens. Before: Passing Everything Through Navigation Params // SomeDocumentScreen.tsx export const SomeDocumentScreen = ({ route }) => { const { navigate } = useNavigation(); // Complex business logic directly in component // Passing all params through, for the next screens const handleNextStep = (path) => { const { firstStepData } = route.params; if (firstStepData) { navigate("SecondStepScreen", { ...route.params, type: "typeB", firstStepData: { ...firstStepData, path } }); } }; const handleRetry = (error) => { const { type, firstStepData } = route.params; const retryInfo = determineRetryPath(error); navigate("RetryStepScreen", { ...route.params, failed: retryInfo.failed, maxAllowedRetries: 0 }); }; return ( // Components UI... ); }; Some screens didn't need more than half of the params, but were forced to accept them because the next screen needed them, which is a direct violation of the interface segregation principle. It became almost impossible to track which screen actually needed which params. We could have continued treating it as nine separate screens, maybe refactored here and there, or moved some data from params to a state manager. That would have been a slight improvement, but still not what I wanted. Instead, I decided to take a step back and look at the whole process from a wider perspective. I immediately noticed that it was really a single, complex process with nine clear steps—each of which could be represented as a separate state with the clear transitions between them. I was excited, this was a perfect case for the finite-state machine pattern! I started planning how to improve this feature, but the complexity made

Hi, my name is Anton. I'm a software developer specializing in cross-platform mobile development, currently working at a fintech company where I help build a neo-banking application.

There's often debate about design patterns—do we really need them, or are they just outdated theory with little practical value in modern software development? I strongly disagree with the idea that patterns are unnecessary. In my view, having a solid foundation in theoretical concepts is extremely valuable. It's like recursion: you might not need it every day, but when you encounter a problem that is recursive in nature—like traversing a file system—you simply can't solve it effectively any other way. The same applies to design patterns. Some processes naturally fit certain patterns, and recognizing them allows you to solve problems in a well-known, structured way. Otherwise, you risk reinventing the wheel—often with a much, much less effective result.

Recently, I was assigned an interesting task at work that proves my point, and I think it's worth sharing.

In my daily work, I'm always looking for patterns that can help implement features more cleanly and maintainably. Since I mostly work on the client side, which is inherently stateful, one of my favorite patterns is the finite-state machine. Even if you know nothing about state machines, you're probably using them unconsciously in your code. The reason is that state machines are incredibly common in our daily lives - they appear in everything from traffic lights and vending machines to smartphone apps and ATMs. Any system that moves through specific states in response to certain inputs or events is essentially a state machine. We interact with them constantly, often without realizing it. But if you use them unconsciously, they usually end up as a messy combination of boolean flags and if statements. It's hard to add new states, and each additional state makes the abstraction worse and worse. It's much better if you can recognize the pattern and organize it properly.

That's exactly the situation we had. My team and I are pretty obsessed with code quality. During a regular upgrade of our dependencies (a routine process in any React Native app), we decided to migrate to the latest version of React Navigation, and as part of that process, refactor some connected features. While investigating what to improve, the identity verification process caught our attention. Like in any banking app, a crucial part of ours is verifying customer identity and documents during onboarding. This is a fairly complex process, involving many steps, and in our app, it was spread across nine screens. And the original implementation, to be honest, was far from ideal. It seemed like previously nobody had tried to see the whole picture. Each screen was treated as a separate entity, and as a result, the logic for each step was spread throughout the functional component body—often 50 to 150 lines of business logic per screen, right in the render method. The communication between screens was also poor. All data was passed through route params, which is fine for primitive values but becomes unwieldy for complex objects used across multiple screens.

Before: Passing Everything Through Navigation Params

// SomeDocumentScreen.tsx

export const SomeDocumentScreen = ({ route }) => {

const { navigate } = useNavigation();

// Complex business logic directly in component

// Passing all params through, for the next screens

const handleNextStep = (path) => {

const { firstStepData } = route.params;

if (firstStepData) {

navigate("SecondStepScreen", {

...route.params,

type: "typeB",

firstStepData: { ...firstStepData, path }

});

}

};

const handleRetry = (error) => {

const { type, firstStepData } = route.params;

const retryInfo = determineRetryPath(error);

navigate("RetryStepScreen", {

...route.params,

failed: retryInfo.failed,

maxAllowedRetries: 0

});

};

return (

// Components UI...

);

};

Some screens didn't need more than half of the params, but were forced to accept them because the next screen needed them, which is a direct violation of the interface segregation principle. It became almost impossible to track which screen actually needed which params. We could have continued treating it as nine separate screens, maybe refactored here and there, or moved some data from params to a state manager. That would have been a slight improvement, but still not what I wanted.

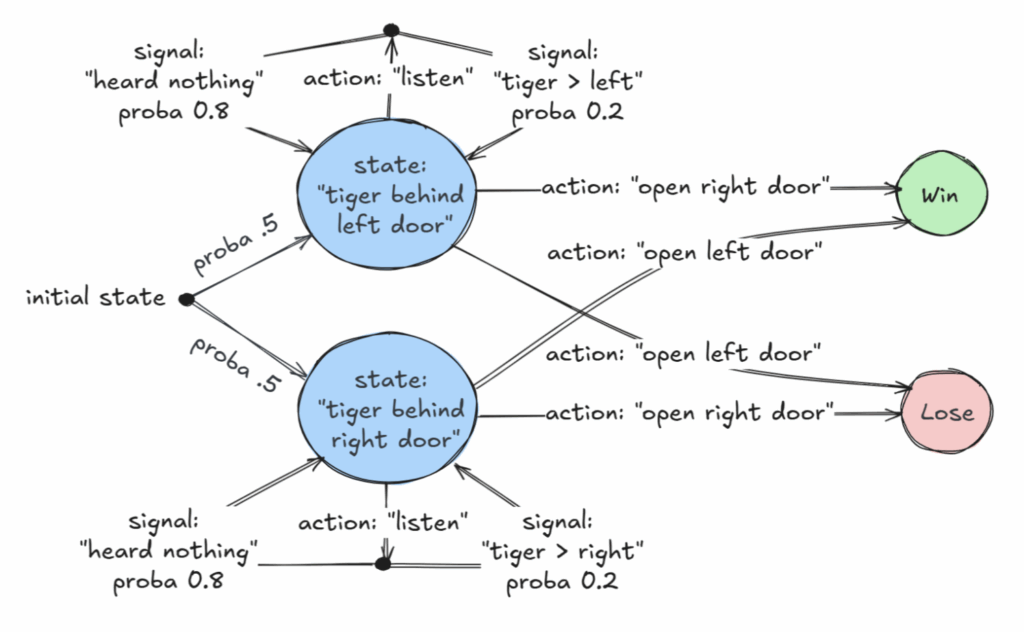

Instead, I decided to take a step back and look at the whole process from a wider perspective. I immediately noticed that it was really a single, complex process with nine clear steps—each of which could be represented as a separate state with the clear transitions between them. I was excited, this was a perfect case for the finite-state machine pattern!

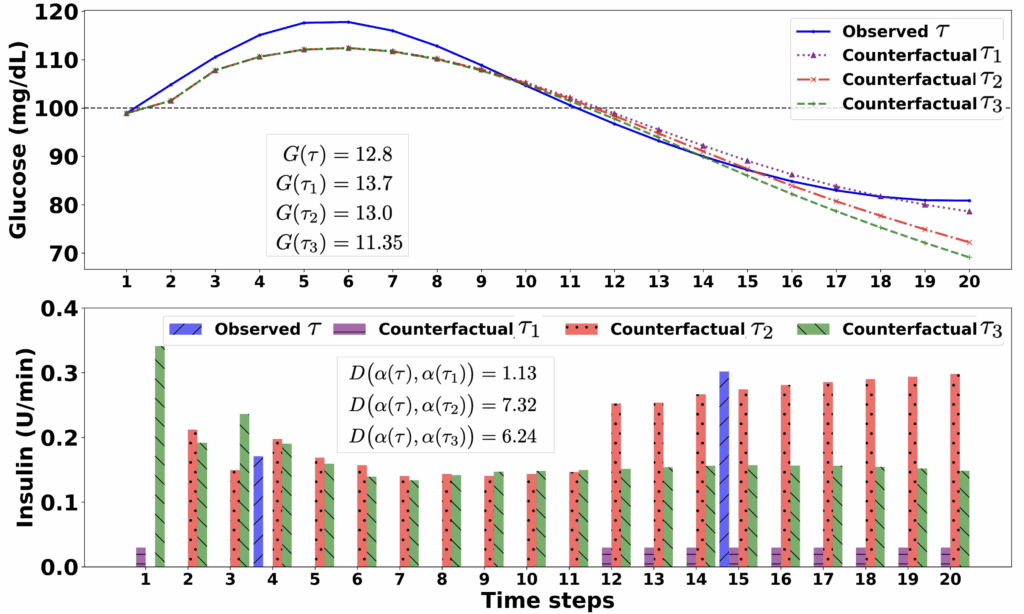

I started planning how to improve this feature, but the complexity made it hard to see the full picture. To help myself, I decided to visualize the process first. I spent about two days preparing a flowchart of the entire process, and only after that did I start working on the implementation.

The Refactoring: Step by Step

I started by creating the structure of the state machine, declaring all the steps, and preparing an object to connect each state to its corresponding screen.

// ProcessSteps.ts

export const processSteps = {

FIRST_STEP: "FirstStep",

SECOND_STEP: "SecondStep",

// Additional steps...

RETRY_STEP: "RetryStep",

} as const;

export type ProcessState = (typeof processSteps)[keyof typeof processSteps];

export const stateToScreen: Record<ProcessState, ScreenNames> = {

[processSteps.FIRST_STEP]: "FirstStepScreen",

[processSteps.SECOND_STEP]: "SecondStepScreen",

// Mapping additional steps to screens...

[processSteps.RETRY_STEP]: "RetryStepScreen",

};

I also wrote navigation helpers to handle the different navigation actions. Since React Navigation v7 requires the navigation object to come from a hook and only be used inside component bodies, I passed it to the state machine transition functions as a dependency.

// Helper functions to handle different navigation actions

export const navigateToState = (

state: ProcessState,

navigate: NavigateFunction,

params?: Record<string, any>

) => {

const screenName = stateToScreen[state];

navigate(screenName, params);

};

export const resetToState = (state: ProcessState, reset: ResetFunction) => {

const screenName = stateToScreen[state];

reset({

index: 0,

routes: [{ name: screenName }],

});

};

export const pushToState = (

state: ProcessState,

dispatch: DispatchFunction

) => {

const screenName = stateToScreen[state];

dispatch(StackActions.push(screenName));

};

Once this preparation was done, I began gradually moving the business logic from each screen into the respective state in my state machine, step by step. This process took at least two weeks, including testing each step to make sure nothing broke. I also made a point not to change the logic itself, since it was already working well—there was no need to make the task even more complicated. I focused solely on changing the structure, making the transition as safe and minimal as possible.

To manage the state of our finite-state machine and house its transition logic, I leveraged our existing client-state management solution, Zustand. The createProcessStore function, shown below, defines this logic. It's worth noting that the FSM pattern itself is flexible; you could implement it with vanilla React hooks, Context API, or other state management libraries. For applications with numerous or highly complex state machines, dedicated libraries like XState are also excellent choices, offering powerful features such as formal definitions, visualizers, and actor model capabilities.

The Result

I was very satisfied with the result. Now, the business logic is encapsulated in one place, and it's easy to understand the whole flow just by looking at the code for each step. In fact, it's so clear and self-documenting that you barely need the flowchart anymore.

// ProcessStore.ts

export const createProcessStore: StateCreator<ProcessStore> = (set, get) => ({

// Initial state

currentState: undefined,

type: undefined,

firstStepData: { path: undefined, success: false, id: undefined },

secondStepData: { path: undefined, success: false, id: undefined },

// Utility methods

clear: () => set(() => initialState),

// State transitions

// Business logic that previously lived in the components body

navigateToFirstStep: (navigate) => {

// Logic to transition to the first step

set((state) => ({

...state,

currentState: processSteps.FIRST_STEP,

type: "typeA",

// Update state related to the transition

}));

navigateToState(processSteps.FIRST_STEP, navigate);

},

navigateToSecondStep: (dispatch, path) => {

// Logic to transition to second step state

set((state) => {

const dataKey = getDataKey(state.type);

return {

...state,

currentState: processSteps.SECOND_STEP,

[dataKey]: { ...state[dataKey], path },

};

});

pushToState(processSteps.SECOND_STEP, dispatch);

},

// Additional state transitions for each step in the process

// ...

// Error handling state transitions

handleRetry: (navigate, failed) => {

// Logic to handle retry logic

set((state) => ({

...state,

currentState: processSteps.RETRY_STEP,

tasksInProgress: { completed: [], remaining: failed },

maxAllowedRetries: 0,

}));

navigateToState(processSteps.RETRY_STEP, navigate, {

// Params to pass ...

});

},

});

The screens themselves became much more "dumb"—they no longer handle any business logic, but simply use the functions provided by the state machine.

// SomeDocumentScreen.tsx

export const SomeDocumentScreen = () => {

const { navigate, dispatch } = useNavigation();

const { navigateToSecondStep, handleRetry } = useProcessStore();

const handleNextStep = (path: string) => {

navigateToSecondStep(dispatch, path);

};

const handleError = (error: Error) => {

const retryInfo = determineRetryPath(error);

handleRetry(navigate, retryInfo.failed);

};

return (

// Components UI...

);

};

While some FSMs use a generic transition function, like proceedToStep(targetState, ...params), I chose specific methods for each state transition (e.g., navigateToSecondStep). This was my conscious decision to maintain clarity ,type safety and simplicity, as each transition in our process had distinct parameter requirements, making a single generic dispatcher less practical for this use case.

As a pleasant side effect, I was able to delete many lines of redundant code that were, in fact, not in use—but it wasn't obvious before, and everyone was afraid to remove it for fear of breaking something. I shudder to think what it would have been like if we had needed to add new features or extend this code in its previous form—it would have been a nightmare. Now, the code is much better structured, clearer, far more maintainable, and easy to extend with new features in the future.

Key Takeaways

Recognize the Pattern: Taking a step back to see the bigger picture revealed that our nine separate screens were actually a single process with distinct states - a perfect match for the finite-state machine pattern.

Centralized Logic: Moving business logic from individual components into a dedicated state machine significantly improved code organization and maintainability.

Cleaner Components: UI components became simpler "dumb" presentational components, focused solely on rendering and user interaction rather than complex business logic.

Self-Documenting Code: The state machine structure made the flow so clear that it serves as documentation - you can understand the entire process just by reviewing the state transitions.

Easier Debugging: Finding and fixing bugs became much simpler with a centralized, structured approach to state management.

Reduced Code: As a bonus, we were able to safely remove redundant code that was previously difficult to identify as unused.

Future-Proofing: Adding new features or states to the process is now straightforward since the pattern scales well with additional complexity.

Theoretical Knowledge Has Practical Value: This real-world example demonstrates why understanding design patterns like finite-state machines remains valuable in modern software development.

The time investment in refactoring (approximately two weeks) has already paid dividends in terms of code quality and maintenance efficiency. What initially seemed like a daunting task - refactoring nine complex screens - became manageable by applying the right pattern to the problem.

Thank you for your attention and happy hacking!

![[The AI Show Episode 156]: AI Answers - Data Privacy, AI Roadmaps, Regulated Industries, Selling AI to the C-Suite & Change Management](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20156%20cover.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

_incamerastock_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Senators reintroduce App Store bill to rein in ‘gatekeeper power in the app economy’ [U]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/06/app-store-senate.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)