This is how it feels at the beginning of the end of the world

“The apocalypse will start having vermouths and tapas,” a friend told me yesterday. Just a day before, the electricity shut down for all of Spain and Portugal, trapping thousands in subways, trains, and elevators for hours, forcing people to walk miles back to their homes, putting hospitals on backup power, and turning off traffic lights, phones, and credit card readers. It shut down everything. Officials are still calculating the economic costs, but it will be in the billions. As this was happening, I still saw the people drinking in bar terraces too, as I was walking up the street to pick up my son early from school. They were joking and making fun. Others were rushing around in a panic like me, some with their kids, some alone. Lines dozens of people long were waiting for buses that came and passed by, overloaded. After everything passed, many celebrated online how refreshing it was to be living without social media or phones. An analog world felt so nice to those who were ignorant about the ultimate consequences of a total blackout for hours or days. Nobody knew that, if this lasted for more than 24 hours, many people would start dying in hospitals and panic would ensue. In 48, we will be out of water or any food supply chains. And, in 72 hours without electricity, civilization as we knew it would be on the brink. “Without electricity, we go back to the Stone Age. Especially in high density urban centers,” Dr. Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi, assistant professor of computing in University of California, Irvine, told me in a conversation about a potential global blackout years ago. “I can’t even imagine what would happen in an event of this scale.” Luckily, that didn’t happen, but it felt like the beginning of the end to me. When the national blackout started at 12:23, on April 28, 2025, I was at home writing, as usual. I noticed that my internet was off at the same time as everyone else in the country. I shrugged. “The building power is down. Probably they are doing some work again outside,” I told myself. I took a break, had the last cup of coffee still warm in my french press. I noticed my phone’s data was off. An hour later, the internet didn’t come back and my cell connection still wasn’t working. Weird. I went outside and saw people rushing. Some were out of their offices, talking. The doorman didn’t know what was going on and mumbled something about the damn government. Thinking it was just my neighborhood, I decided to go to a café by my son’s school. That’s when I passed by the first traffic light. It, too, was off. At that point I suddenly got extremely worried. A police helicopter zoomed by at low altitude. “This is how the world ends,” I told myself. Spectators roam the grounds of the Mutua Madrid Open tennis tournament after a power outage forced the cancellation of play on April 28, 2025. [Photo: Oscar J. Barroso/Europa Press/Getty Images] Where are all the zombies? I wasn’t expecting zombies. Okay, maybe for a split second (The Last of Us Season 2 is intense). A couple years ago, I wrote and directed a short documentary on how a major solar storm—something called a Carrington Event—could take down the entire civilization. The phenomenon made telegraph poles burn down back in 1859 but, today, when everything depends on electricity, experts told me that it would probably cripple our entire civilization. Not for 12 hours. Not for a day. But, for decades, according to the Pentagon and the National Academy of Sciences. John Kappenman, an American engineer with decades of experience in the North American electrical industry, painted a dire picture: “Yes, there would clearly be public health disasters, public service disasters, disasters in the food distribution chain, disasters in the pharmaceutical industry, collapse of hospitals and ERs, payment systems. . . . Everything will fall once you suffer an impact on the most important of all infrastructure, the power grid,” he said. I spoke with scientists from NASA. Everyone told me the same thing. And everyone insisted that we urgently needed to set up better early warning systems and reconfigure power networks throughout the world to make them more independent from each other. We needed to install surge suppression systems capable of absorbing the energy overload from such a solar event, and stockpile industrial transformers, which right now take about two years to make and deliver (most of them, from China, of course!). “It’s not a question about whether we are going to suffer one of these events or not. It’s a question about when it is going to happen,” Holly Gilbert—the former director of the heliophysical science division of the NASA Goddard research center who now heads the High Altitude Observatory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research of the United States—told me back then. [Photo: Alejandro Martinez Velez/Europa Press/Getty Images] A surreal experience So you have to excuse my contained panic

“The apocalypse will start having vermouths and tapas,” a friend told me yesterday.

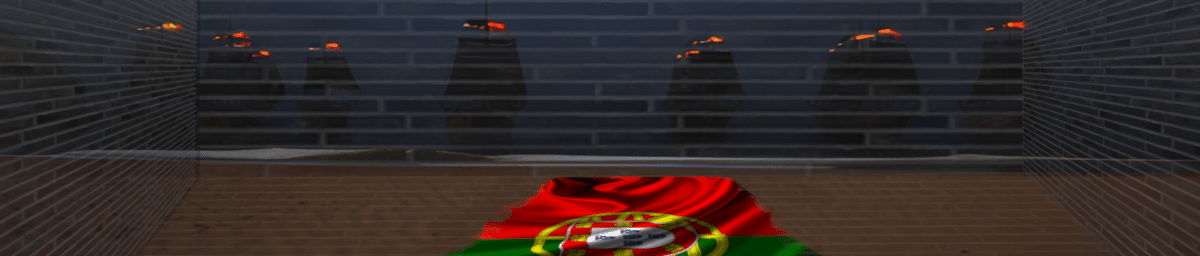

Just a day before, the electricity shut down for all of Spain and Portugal, trapping thousands in subways, trains, and elevators for hours, forcing people to walk miles back to their homes, putting hospitals on backup power, and turning off traffic lights, phones, and credit card readers. It shut down everything. Officials are still calculating the economic costs, but it will be in the billions.

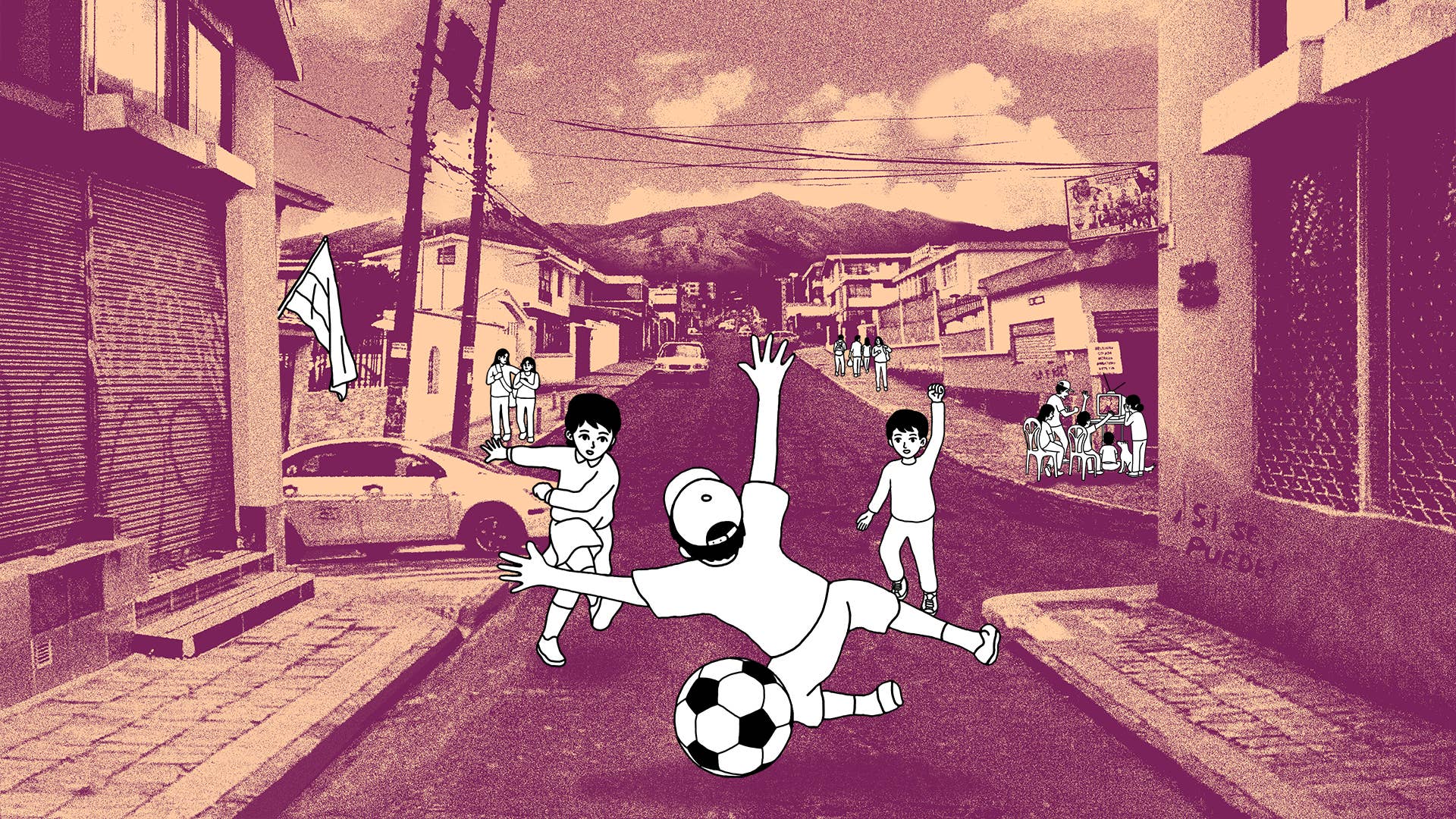

As this was happening, I still saw the people drinking in bar terraces too, as I was walking up the street to pick up my son early from school. They were joking and making fun. Others were rushing around in a panic like me, some with their kids, some alone. Lines dozens of people long were waiting for buses that came and passed by, overloaded.

After everything passed, many celebrated online how refreshing it was to be living without social media or phones. An analog world felt so nice to those who were ignorant about the ultimate consequences of a total blackout for hours or days. Nobody knew that, if this lasted for more than 24 hours, many people would start dying in hospitals and panic would ensue. In 48, we will be out of water or any food supply chains. And, in 72 hours without electricity, civilization as we knew it would be on the brink. “Without electricity, we go back to the Stone Age. Especially in high density urban centers,” Dr. Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi, assistant professor of computing in University of California, Irvine, told me in a conversation about a potential global blackout years ago. “I can’t even imagine what would happen in an event of this scale.”

Luckily, that didn’t happen, but it felt like the beginning of the end to me. When the national blackout started at 12:23, on April 28, 2025, I was at home writing, as usual. I noticed that my internet was off at the same time as everyone else in the country. I shrugged. “The building power is down. Probably they are doing some work again outside,” I told myself. I took a break, had the last cup of coffee still warm in my french press. I noticed my phone’s data was off. An hour later, the internet didn’t come back and my cell connection still wasn’t working. Weird. I went outside and saw people rushing. Some were out of their offices, talking. The doorman didn’t know what was going on and mumbled something about the damn government. Thinking it was just my neighborhood, I decided to go to a café by my son’s school.

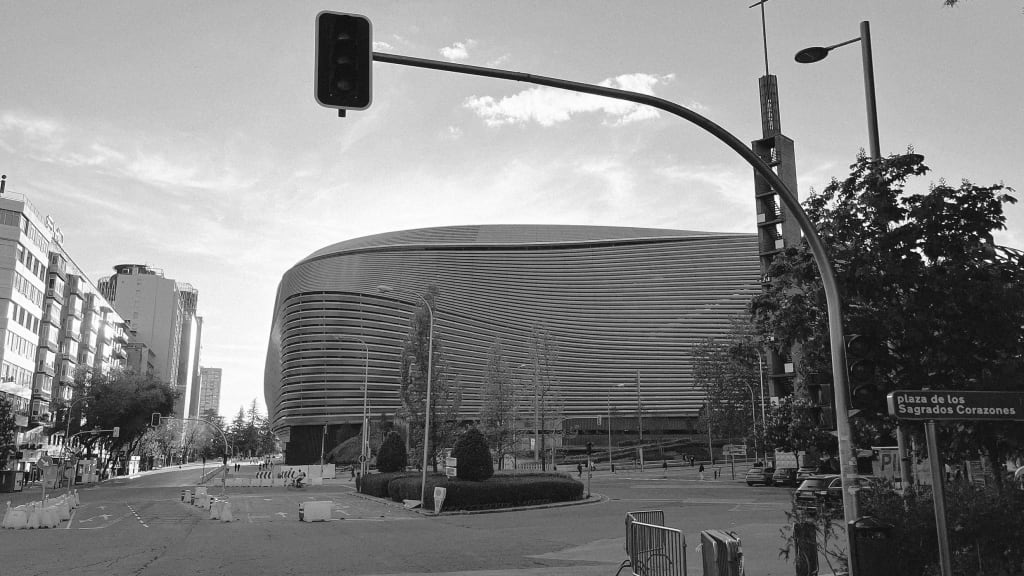

That’s when I passed by the first traffic light. It, too, was off. At that point I suddenly got extremely worried. A police helicopter zoomed by at low altitude. “This is how the world ends,” I told myself.

Where are all the zombies?

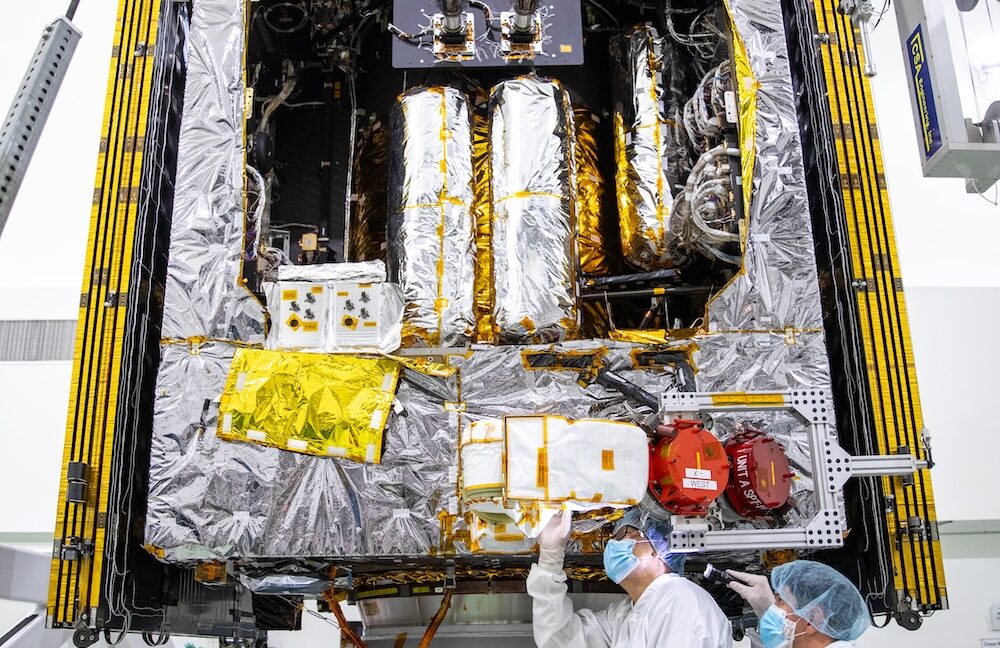

I wasn’t expecting zombies. Okay, maybe for a split second (The Last of Us Season 2 is intense). A couple years ago, I wrote and directed a short documentary on how a major solar storm—something called a Carrington Event—could take down the entire civilization. The phenomenon made telegraph poles burn down back in 1859 but, today, when everything depends on electricity, experts told me that it would probably cripple our entire civilization. Not for 12 hours. Not for a day. But, for decades, according to the Pentagon and the National Academy of Sciences.

John Kappenman, an American engineer with decades of experience in the North American electrical industry, painted a dire picture: “Yes, there would clearly be public health disasters, public service disasters, disasters in the food distribution chain, disasters in the pharmaceutical industry, collapse of hospitals and ERs, payment systems. . . . Everything will fall once you suffer an impact on the most important of all infrastructure, the power grid,” he said.

I spoke with scientists from NASA. Everyone told me the same thing. And everyone insisted that we urgently needed to set up better early warning systems and reconfigure power networks throughout the world to make them more independent from each other. We needed to install surge suppression systems capable of absorbing the energy overload from such a solar event, and stockpile industrial transformers, which right now take about two years to make and deliver (most of them, from China, of course!).

“It’s not a question about whether we are going to suffer one of these events or not. It’s a question about when it is going to happen,” Holly Gilbert—the former director of the heliophysical science division of the NASA Goddard research center who now heads the High Altitude Observatory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research of the United States—told me back then.

A surreal experience

So you have to excuse my contained panic when I started to assume the worst—even as, within minutes, the lack of transformers on fire proved I was just paranoid. I could still hear the ambulance, police, and firefighter sirens howling, and I saw the cars starting to pile up in long traffic jams. But drivers and pedestrian alike were incredibly polite and chill.

My mind, still searching for a culprit, jumped from solar interference to the war in Ukraine and Putin. Could this be a cyberattack? I got to the café and asked the owner, Francesco, if he knew anything. “My father sent me a message from Italy. I got it in a brief moment of signal,” he said (I guessed and confirmed later that some people had connections that were coming and going because their cell provider had towers with backup power units). “He said that Spain, Portugal, and the south of Spain are down.” It had to be an attack. Well, that, or some monumental incompetence with the power lines.

I decided to get my son from school right away. He was startled by the situation and he asked if the Russians could nuke Madrid. I told him no. I told myself yes. I knew a major cyberattack taking communications and power down would be the opening notes of a full war. I walked with him back home, easing his fears and making it all a game. We noticed hundreds of people walking alongside us. People out of their offices. People with kids.

Many were carrying big water bottles and supermarket bags. “Don’t forget to fill your bath tubs,” I told a couple. They laughed nervously, thinking I was joking. I wasn’t. Others were carrying suitcases. “Are they leaving” I kept asking myself. Scenes from the documentary kept coming to my mind. “The first people start leaving the city hours after the hit,” the voice over was narrating in my head.

I knew that fridges—at homes, restaurants, and supermarkets—were off. With no credit card readers—since there was no cell coverage for the most part—shops were shutting down. Some bars were open (it’s Spain!) but only cash payments were possible. TV and routers went off at homes. Some had solar panels and batteries, so they could still access the internet, while many were in their cars parked in the street listening to the radio, the only source of information. The government had no idea what was happening. The President only appeared to say that he didn’t know anything five hours after the shutdown. This would have been unthinkable in any other serious European country. The national power grid company said electricity may be on in six hours but, for most of Spain, it didn’t come after much later.

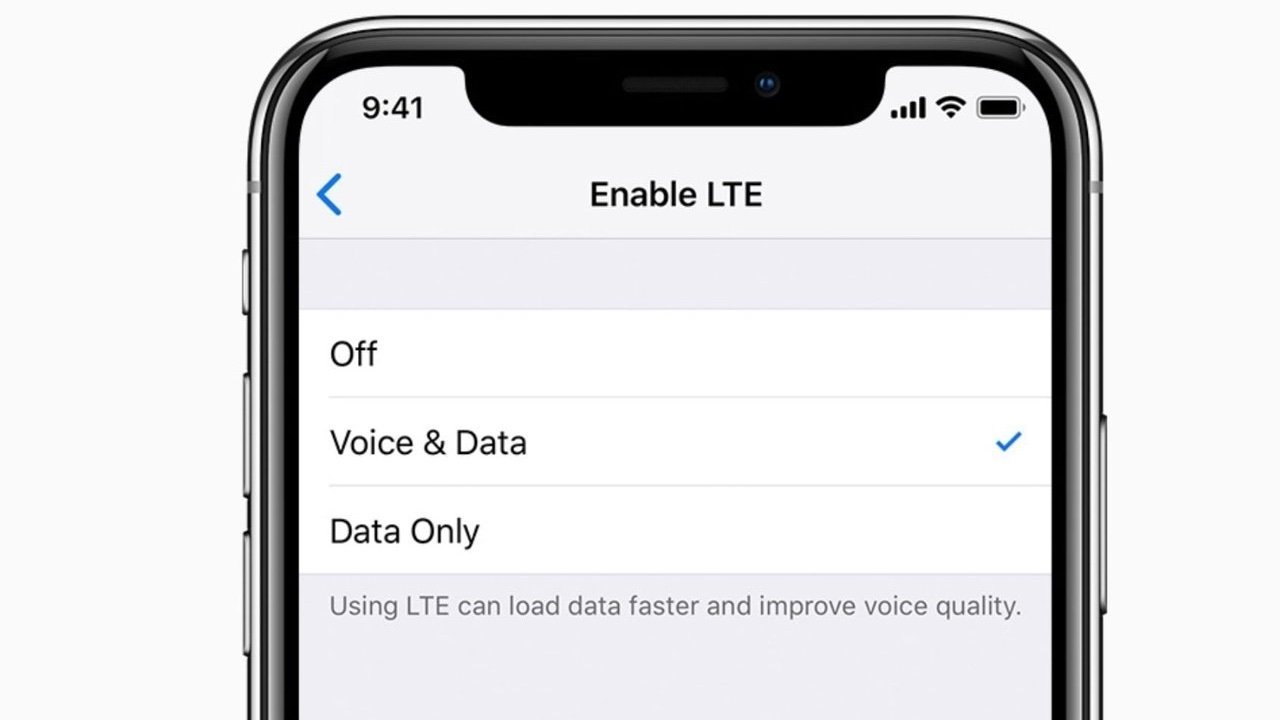

As we were walking home, I noticed people searching for cell bars. Some of them were texting. I raised my phone trying to find a connection, like a diviner in search of water. My phone showed 5G and two bars. The internet worked for a few seconds and a torrent of messages poured in. Friends. Work. Family. Then I managed to call my brother for a few seconds. The 5G turned to 4G, then 3G then E. Then nothing.

I got bits of info from other people and realized how everything I’d learned researching the documentary was becoming a reality. Hospitals were on emergency power. Surgeries got cancelled. I knew that, after 12 hours, we may start seeing generators running out of fuel. Without energy, people on respirators could start dying in the first 24 hours. People who needed dialysis or other electric devices to survive would die in a few days. Blood banks and some drugs would quickly start going bad, too.

I learned that some buildings in Barcelona lost water pressure. Without electricity, their pumps couldn’t get water to the higher floors. I already had filled bath tubs and bottles with water. Just in case. After 24 hours, I knew things could get really bad. Logistics would stop. Major distribution centers would stop working. Cities would become rat traps. The water supply be cut off for most part in every city. The admirable civic attitude of the first hours would get replaced by desperation and panic. Supermarkets would be emptied. Elderly people in need of oxygen and care would be at risk.

In 72 hours, the experts told me, civilization as we know it would just end.

The weird feeling of seeing the world standing still

My brain was racing but I put it all aside. I knew this was an extreme case. I learned that the rest of the world was fine. Europe was okay. We were okay. I went back out with my son because I didn’t have a cell signal at home. We went to the park.

When we arrived, I saw all the families. At this time, nobody would be at the park on a typical weekday. But, without anything to do, there were parents and their kids, just hanging out, and commenting on what was going on. I overheard that all radios were sold out at Chinese bazaars and shops. No batteries either. And supermarkets were already out of water.

But people seemed weirdly calm. It was almost picturesque.

My son and I returned home after playing some soccer. We had dinner (luckily, we have a garden and a small grill, so I fired some wood and we had a feast of chorizos and blood sausage before they went bad in the fridge). We watched some Andor on my laptop. He brushed his teeth and went to bed using the light of my iPhone.

It was just a little different than normal. He told me “I love you” and “goodnight.” And I went back to wait. It wasn’t until 11:30 p.m. when my neighborhood got the power back.

It was a relief, but we still don’t entirely know what happened. We know that it wasn’t an extreme solar weather event, like some rumors from Portugal suggested. That would have fried everything electrical, worldwide. We also know that the European Union and the electrical companies said it wasn’t a cyberattack. The Spanish national power grid company said that 15 gigawatts coming from solar panels disappeared, a sign of what appears to be a terrible design of the power network and the lack of batteries that sustain Spain’s electric network, 71% of which comes from renewable energy. It seems that, for years, the current Spanish government has failed to architect its network to match the amount of solar and wind power we are producing. It’s a dreadful error that will now cost the country billions of dollars.

But it was over. Alone in my room at night, brushing my teeth with my battery-powered toothbrush looking at the torrent of news and messages in my revived phone, I couldn’t think of anything else but how mundane everything seemed at that point and, at the same time, how close we all came from dodging the bullet that may one day end modern life as we know it.

We got really lucky. Because nobody was ready for this. Not the companies, not the government, not the people—the latter of whom were so civil and nice and, luckily, so naive about how everything could have unfolded.

I figured out that the world wouldn’t begin its final days with zombies invading out of nowhere. No, I thought, the zombies this evening are all of us still caught in a stupor. They are the thousands of people spending the night in frozen trains, waiting to be rescued by the military. The people sleeping in their homes after getting drunk with friends or alone. The wandering humans walking miles to their homes. Or this single dad having grilled chorizo with his kid, playing with him, putting him to sleep, and then impatiently waiting for lights and the internet to come back alive, staring blank at a bathtub full of water, planning how we could escape a city of seven million people and head to Cádiz in case things went truly wrong next time.

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] Mail Backup X Individual Edition: Lifetime Subscription (72% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

_Andreas_Prott_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Severance-inspired keyboard could cost up to $699 – have your say [Video]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/05/Severance-inspired-keyboard-could-cost-up-to-699-%E2%80%93-have-your-say-Video.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Ships 55 Million iPhones, Claims Second Place in Q1 2025 Smartphone Market [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97185/97185/97185-640.jpg)