Falling Down The Land Camera Rabbit Hole

It was such an innocent purchase, a slightly grubby and scuffed grey plastic box with the word “P O L A R O I D” intriguingly printed along its top …read more

It was such an innocent purchase, a slightly grubby and scuffed grey plastic box with the word “P O L A R O I D” intriguingly printed along its top edge. For a little more than a tenner it was mine, and I’d just bought one of Edwin Land’s instant cameras. The film packs it takes are now a decade out of production, but my Polaroid 104 with its angular 1960s styling and vintage bellows mechanism has all the retro-camera-hacking appeal I need. Straight away I 3D printed an adapter and new back allowing me to use 120 roll film in it, convinced I’d discover in myself a medium format photographic genius.

But who wouldn’t become fascinated with the film it should have had when faced with such a camera? I have form on this front after all, because a similar chance purchase of a defunct-format movie camera a few years ago led me into re-creating its no-longer-manufactured cartridges. I had to know more, both about the instant photos it would have taken, and those film packs. How did they work?

A Print, Straight From The Camera

In conventional black-and-white photography the film is exposed to the image, and its chemistry is changed by the light where it hits the emulsion. This latent image is rolled up with all the others in the film, and later revealed in the developing process. The chemicals cause silver particles to precipitate, and the resulting image is called a negative because the silver particles make it darkest where the most light hit it. Positive prints are made by exposing a fresh piece of film or photo paper through this negative, and in turn developing it. My Polaroid camera performed this process all-in-one, and I was surprised to find that behind what must have been an immense R&D effort to perfect the recipe, just how simple the underlying process was.

My dad had a Polaroid pack film camera back in the 1970s, a big plastic affair that he used to take pictures of the things he was working on. Pack film cameras weren’t like the motorised Polaroid cameras of today with their all-in-one prints, instead they had a paper tab that you pulled to release the print, and a peel-apart system where after a time to develop, you separated the negative from the print. I remember as a youngster watching this process with fascination as the image slowly appeared on the paper, and being warned not to touch the still-wet print or negative when it was revealed. What I was looking at wasn’t a negative printing process as described in the previous paragraph but something else, one in which the unexposed silver halide compounds which make the final image are diffused onto the paper from the less-exposed areas of the negative, forming a positive image of their own when a reducing agent precipitates out their silver crystals. Understanding the subtleties of this process required a journey back to the US Patent Office in the middle of the 20th century.

It’s All In The Diffusion

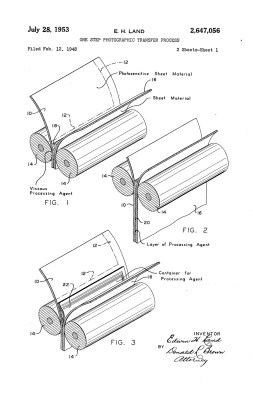

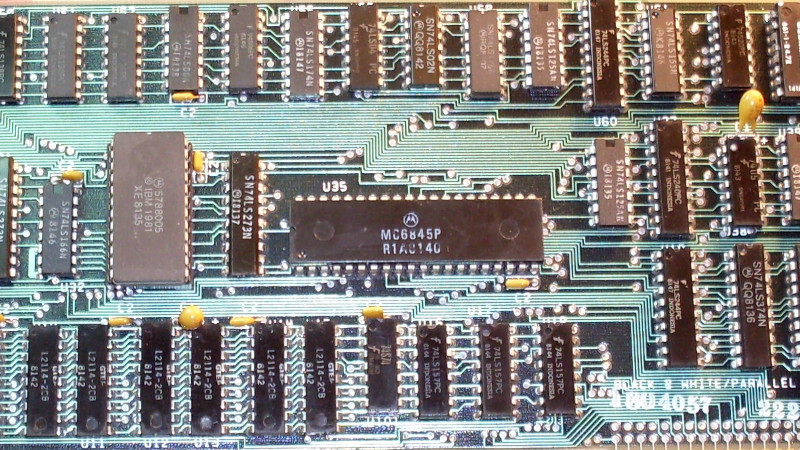

It’s in US2647056 that we find a comprehensive description of the process, and the first surprise is that the emulsion on the negative is the same as on a contemporary panchromatic black-and-white film. The developer and fixer for this emulsion are also conventional, and are contained in a gel placed in a pouch at the head of the photograph. When the exposed film is pulled out of the camera it passes through a set of rollers that rupture this pouch, and then spread the gel in a thin layer between the negative and the coated paper. This gel has two functions: it develops the negative, but over a longer period it provides a wet medium for those unexposed silver halides to diffuse through into the now-also-wet coating of the paper which will become the print. This coating contains a reducing agent, in this case a metalic sulphide, which over a further period precipitates out the silver that forms the final visible image. This is what gives Polaroid photographs their trademark slow reveal as the chemistry does its job.

I’ve just described the black and white process; the colour version uses the same diffusion mechanism but with colour emulsions and dye couplers in place of the black-and-white chemistry. Meanwhile modern one-piece instant processes from Polaroid and Fuji have addressed the problem of making the image visible from the other side of the paper, removing the need for a peel-apart negative step.

Given that the mechanism and chemistry are seemingly so simple, one might ask why we can no longer buy two-piece Polaroid pack or roll film except for limited quantities of hand-made packs from One Instant. The answer lies in the complexity of the composition, for while it’s easy to understand how it works, it remains difficult to replicate the results Polaroid managed through a huge amount of research and development over many decades. Even the Impossible Project, current holders of the Polaroid brand, faced a significant effort to completely replicate the original Polaroid versions of their products when they brought the last remaining Polaroid factory to production back in 2010 using the original Polaroid machinery. So despite it retaining a fascination among photographers, it’s unlikely that we’ll see peel-apart film for Polaroid cameras return to volume production given the small size of the potential market.

Hacking A Sixty Year Old Camera

So having understood how peel-apart pack film works and discovered what is available here in 2025, what remains for the camera hacker with a Land camera? Perhaps the simplest idea would be to buy one of those One Instant packs, and use it as intended. But we’re hackers, so of course you will want to print that 120 conversion kit I mentioned, or find an old pack film cartridge and stick a sheet of photographic paper or even a Fuji Instax sheet in it. You’ll have to retreat to the darkroom and develop the film or run the Instax sheet through an Instax camera to see your images, but it’s a way to enjoy some retro photographic fun.

Further than that, would it be possible to load Polaroid 600 or i-Type sheets into a pack film cartridge and somehow give them paper tabs to pull through those rollers and develop them? Possibly, but all your images would be back to front. Sadly, rear-exposing Instax Wide sheets wouldn’t work either because their developer pod lies along their long side. If you were to manage loading a modern instant film sheet into a cartridge, you’d then have to master the intricate paper folding arrangement required to ensure the paper tabs for each photograph followed each other in turn. I have to admit that I’ve become fascinated by this in considering my Polaroid camera. Finally, could you make your own film? I would of course say no, but incredibly there are people who have achieved results doing just that.

My Polaroid 104 remains an interesting photographic toy, one I’ll probably try a One Instant pack in, and otherwise continue with the 3D printed back and shoot the occasional 120 roll film. If you have one too, you might find my 3D printed AAA battery adapter useful. Meanwhile it’s the cheap model without the nice rangefinder so it’ll never be worth much, so I might as well just enjoy it for what it is. And now I know a little bit more about his invention, admire Edwin Land for making it happen.

Any of you out there hacking on Polaroids?

![[The AI Show Episode 147]: OpenAI Abandons For-Profit Plan, AI College Cheating Epidemic, Apple Says AI Will Replace Search Engines & HubSpot’s AI-First Scorecard](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20147%20cover.png)

![How to Enable Remote Access on Windows 10 [Allow RDP]](https://bigdataanalyticsnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/remote-access-windows.jpg)

![[DEALS] The 2025 Ultimate GenAI Masterclass Bundle (87% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Legends Reborn tier list of best heroes for each class [May 2025]](https://media.pocketgamer.com/artwork/na-33360-1656320479/pg-magnum-quest-fi-1.jpeg?#)

-Olekcii_Mach_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Brian_Jackson_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Watch Aston Martin and Top Gear Show Off Apple CarPlay Ultra [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97336/97336/97336-640.jpg)

![Trump Tells Cook to Stop Building iPhones in India and Build in the U.S. Instead [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97329/97329/97329-640.jpg)