Basics of Animal Tracking Databases: Crafting the Schema

“ChatGPT, whip up a next-gen animal tracking database for me…” In my last post, Basics of Animal Tracking Databases, we nailed the essentials: core entities, a tight data model, and why SQL is the MVP for most tracking gigs. Now, let’s get our hands dirty and actually build a PostgreSQL schema. Who doesn’t love a good, structured database? Why PostgreSQL? PostgreSQL is the Swiss Army knife of SQL databases. It’s got structured data, rock-solid relationships, and ACID compliance, plus it’s free and open-source. For our median Movebank study (10 tags, 10,000 locations), it’s a perfect fit. We’ll use it to bring five key entities to life: Study, Tag, Animal, Deployment, and Location. Let’s build this thing. Setting the Stage First, we need a fresh sandbox. Fire up your PostgreSQL tool of choice (psql, pgAdmin, whatever vibes with you) and run: -- Create the database to house our tracking data CREATE DATABASE animal_tracking; -- Connect to it \c animal_tracking -- Set up a schema for organization CREATE SCHEMA tracking; Boom. A clean database and a tracking schema to keep our tables organized. Simple but effective. Crafting the Schema Here’s the fun part: turning our data model into tables. Five entities, each with fields, keys, and relationships, ready to handle real tracking data. Let’s roll. Let's revisit the Entity-Relationship diagram from the previous post: Study The study table is our anchor. Everything ties back to it. -- Table for research studies, the top-level entity CREATE TABLE tracking.study ( study_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each study study_name TEXT NOT NULL -- Human-readable study name ); study_id is our unique identifier. study_name gives it a readable label. Easy peasy. Tag Next up, tag. This is the hardware pumping out data, linked to a study. -- Table for tracking devices CREATE TABLE tracking.tag ( tag_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each tag study_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.study(study_id), -- Link to parent study tag_manufacturer TEXT, -- Optional: who made the tag tag_model TEXT -- Optional: tag model details ); study_id hooks each tag to its study with a foreign key. Manufacturer and model are optional for flexibility. Animal The animal table is for our stars: wolves, eagles, you name it. -- Table for tracked animals CREATE TABLE tracking.animal ( animal_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each animal study_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.study(study_id), -- Link to parent study animal_name TEXT, -- Optional: name or identifier animal_sex CHAR(1), -- M/F/U for male, female, unknown animal_species TEXT -- Species name ); Another study_id foreign key keeps animals tied to their study. animal_sex is M/F/U (unknown). Short and sweet. Deployment The deployment table is the glue, linking tags to animals over time. -- Table to track when tags are attached to animals CREATE TABLE tracking.deployment ( deployment_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each deployment study_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.study(study_id), -- Link to study tag_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.tag(tag_id), -- Link to tag animal_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.animal(animal_id), -- Link to animal deployment_start_timestamp TIMESTAMP NOT NULL, -- When tag was attached deployment_end_timestamp TIMESTAMP -- When tag was removed (nullable if active) ); Three foreign keys and timestamps track when a tag’s on duty. deployment_end_timestamp stays nullable for active deployments. Location Finally, location. This is where the magic happens: GPS points from tags. -- Table for GPS location data generated by tags CREATE TABLE tracking.location ( tag_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.tag(tag_id), -- Link to tag generating data location_longitude DECIMAL, -- Longitude location_latitude DECIMAL, -- Latitude location_timestamp TIMESTAMP NOT NULL -- When the point was recorded ); tag_id ties each point to its device. This design assumes GPS data is tied to tags, not animals directly. Use the deployment table to find out which animal wore the tag at any point in time. Double-Checking Run this in psql to make sure everything’s there: -- List all tables in the tracking schema \dt tracking.* You should see: study, tag, animal, deployment, and location. If they’re listed, we’re in business! Quick Recap Table Purpose study Top-level research project tag GPS tracking hardware animal The tracked individual (e.g., wolf) deployment Connects tag to animal over

“ChatGPT, whip up a next-gen animal tracking database for me…”

In my last post, Basics of Animal Tracking Databases, we nailed the essentials: core entities, a tight data model, and why SQL is the MVP for most tracking gigs. Now, let’s get our hands dirty and actually build a PostgreSQL schema. Who doesn’t love a good, structured database?

Why PostgreSQL?

PostgreSQL is the Swiss Army knife of SQL databases. It’s got structured data, rock-solid relationships, and ACID compliance, plus it’s free and open-source. For our median Movebank study (10 tags, 10,000 locations), it’s a perfect fit.

We’ll use it to bring five key entities to life: Study, Tag, Animal, Deployment, and Location.

Let’s build this thing.

Setting the Stage

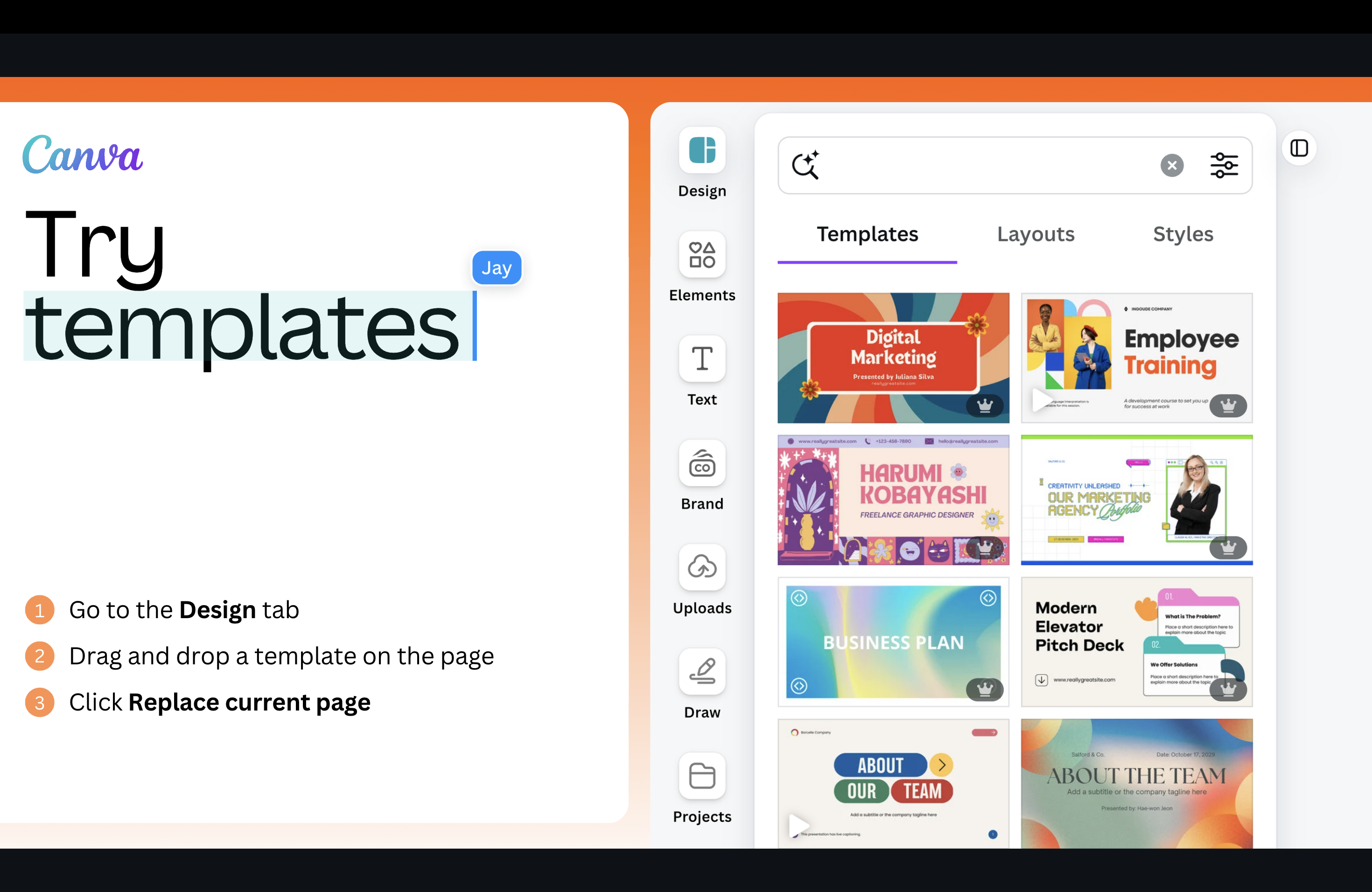

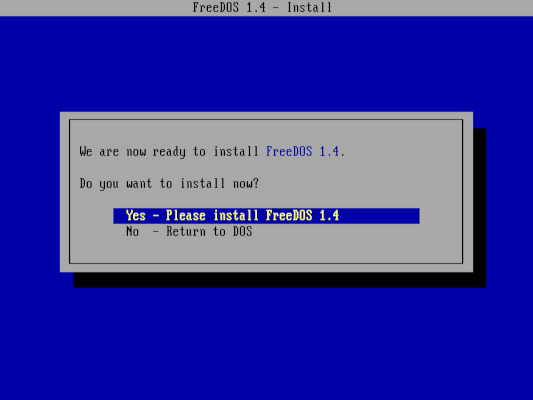

First, we need a fresh sandbox. Fire up your PostgreSQL tool of choice (psql, pgAdmin, whatever vibes with you) and run:

-- Create the database to house our tracking data

CREATE DATABASE animal_tracking;

-- Connect to it

\c animal_tracking

-- Set up a schema for organization

CREATE SCHEMA tracking;

Boom. A clean database and a tracking schema to keep our tables organized. Simple but effective.

Crafting the Schema

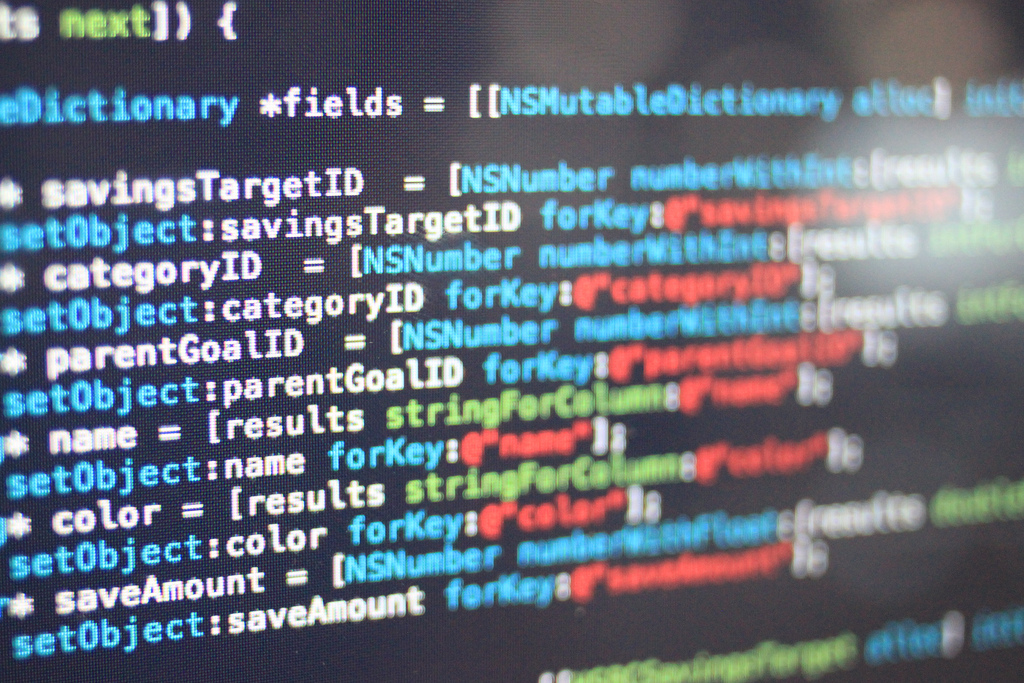

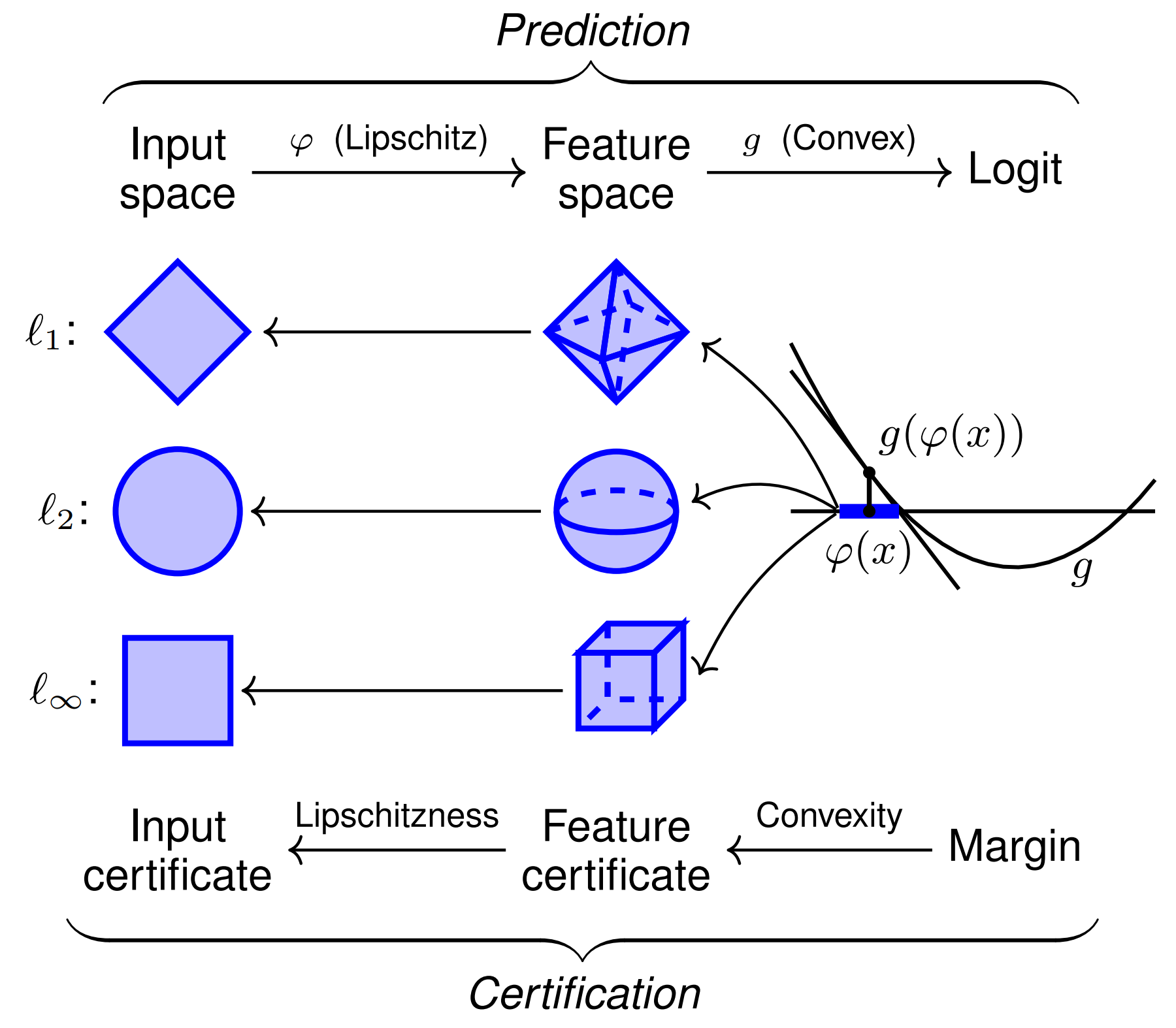

Here’s the fun part: turning our data model into tables. Five entities, each with fields, keys, and relationships, ready to handle real tracking data. Let’s roll.

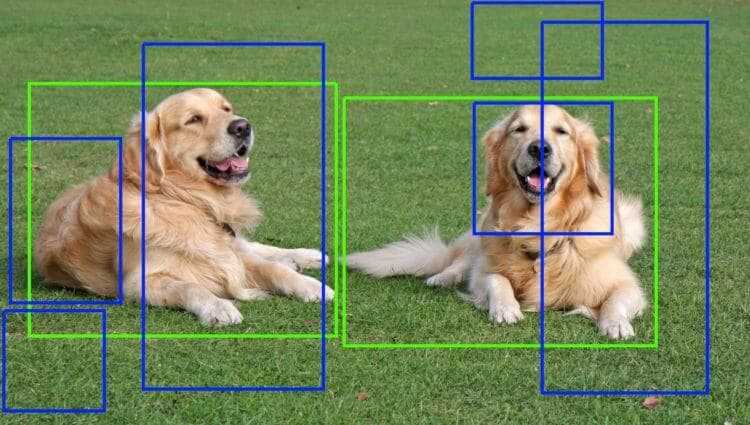

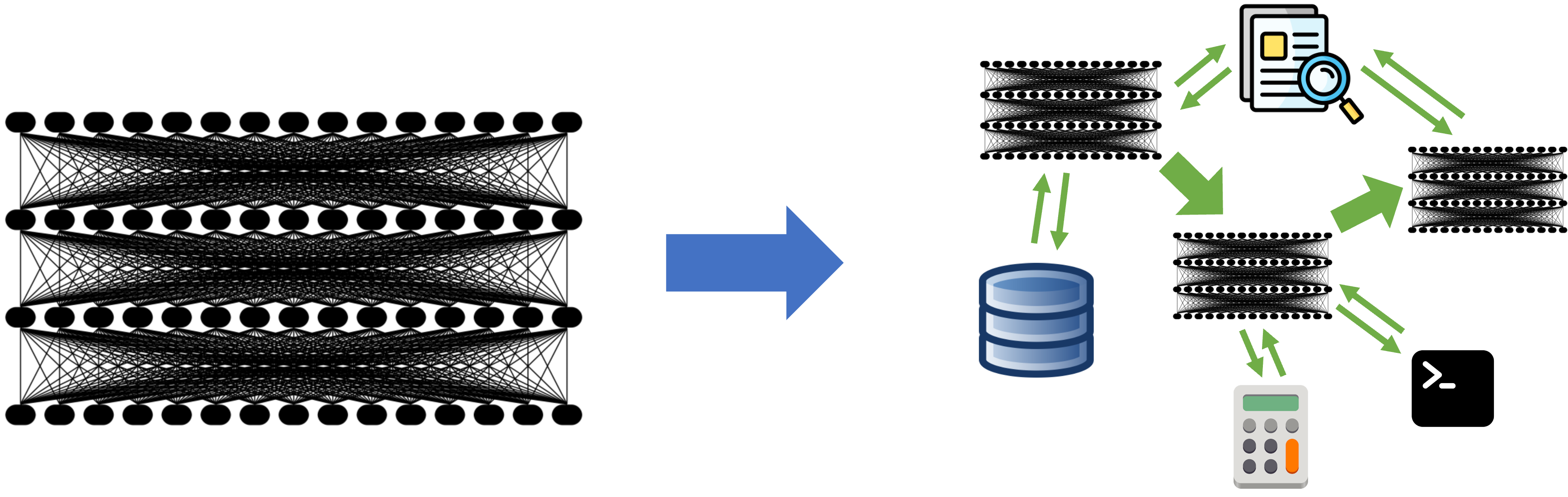

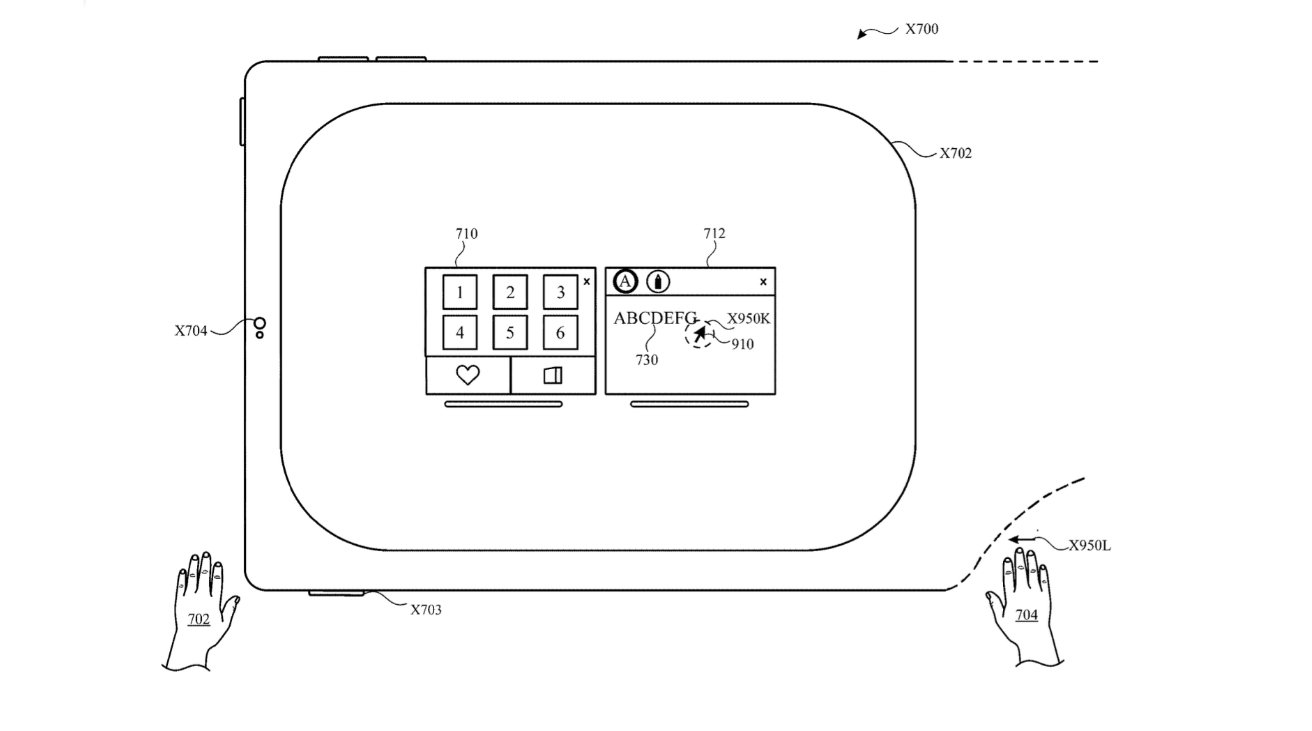

Let's revisit the Entity-Relationship diagram from the previous post:

Study

The study table is our anchor. Everything ties back to it.

-- Table for research studies, the top-level entity

CREATE TABLE tracking.study (

study_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each study

study_name TEXT NOT NULL -- Human-readable study name

);

study_id is our unique identifier. study_name gives it a readable label. Easy peasy.

Tag

Next up, tag. This is the hardware pumping out data, linked to a study.

-- Table for tracking devices

CREATE TABLE tracking.tag (

tag_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each tag

study_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.study(study_id), -- Link to parent study

tag_manufacturer TEXT, -- Optional: who made the tag

tag_model TEXT -- Optional: tag model details

);

study_id hooks each tag to its study with a foreign key. Manufacturer and model are optional for flexibility.

Animal

The animal table is for our stars: wolves, eagles, you name it.

-- Table for tracked animals

CREATE TABLE tracking.animal (

animal_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each animal

study_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.study(study_id), -- Link to parent study

animal_name TEXT, -- Optional: name or identifier

animal_sex CHAR(1), -- M/F/U for male, female, unknown

animal_species TEXT -- Species name

);

Another study_id foreign key keeps animals tied to their study. animal_sex is M/F/U (unknown). Short and sweet.

Deployment

The deployment table is the glue, linking tags to animals over time.

-- Table to track when tags are attached to animals

CREATE TABLE tracking.deployment (

deployment_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -- Unique ID for each deployment

study_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.study(study_id), -- Link to study

tag_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.tag(tag_id), -- Link to tag

animal_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.animal(animal_id), -- Link to animal

deployment_start_timestamp TIMESTAMP NOT NULL, -- When tag was attached

deployment_end_timestamp TIMESTAMP -- When tag was removed (nullable if active)

);

Three foreign keys and timestamps track when a tag’s on duty. deployment_end_timestamp stays nullable for active deployments.

Location

Finally, location. This is where the magic happens: GPS points from tags.

-- Table for GPS location data generated by tags

CREATE TABLE tracking.location (

tag_id INTEGER REFERENCES tracking.tag(tag_id), -- Link to tag generating data

location_longitude DECIMAL, -- Longitude

location_latitude DECIMAL, -- Latitude

location_timestamp TIMESTAMP NOT NULL -- When the point was recorded

);

tag_id ties each point to its device. This design assumes GPS data is tied to tags, not animals directly. Use the deployment table to find out which animal wore the tag at any point in time.

Double-Checking

Run this in psql to make sure everything’s there:

-- List all tables in the tracking schema

\dt tracking.*

You should see: study, tag, animal, deployment, and location. If they’re listed, we’re in business!

Quick Recap

| Table | Purpose |

|---|---|

| study | Top-level research project |

| tag | GPS tracking hardware |

| animal | The tracked individual (e.g., wolf) |

| deployment | Connects tag to animal over time |

| location | Stores GPS coordinates from tags |

What’s Next?

We’ve got a lean, mean schema. It’s relational, structured, and ready to rock.

Next time, we’ll load it with some tracking data and start querying the heck out of it. Got a specific angle you’d like to explore next—spatial queries, performance tips, or real-time ingestion? Drop me a line. Let’s build it together.

About the Author

Matthias Berger has been a key member of the Movebank Development Team since its inception in 2008, contributing to the advancement of animal tracking databases and supporting researchers worldwide.

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

![From drop-out to software architect with Jason Lengstorf [Podcast #167]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1743796461357/f3d19cd7-e6f5-4d7c-8bfc-eb974bc8da68.png?#)

_Zoonar_GmbH_Alamy.jpg?#)

(1).webp?#)

![Are you buying a new Apple product to avoid tariffs? [Poll]](https://9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/03/tim-cook-apple-fifth-ave-joz.jpg?quality=82&strip=all&w=290&h=145&crop=1)

![New iOS 19 Leak Allegedly Reveals Updated Icons, Floating Tab Bar, More [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96958/96958/96958-640.jpg)

![Apple to Source More iPhones From India to Offset China Tariff Costs [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96954/96954/96954-640.jpg)