Refactor-First, Feature-Last: Conversing with Code

Two months into my no-code-writing development experiment, I've started to reflect on what I've gained and lost in the process. There are clear wins: faster prototyping, more exploratory design conversations before touching code, and almost no actual coding (which is a huge relief, I'm more of an organize-ideas person, not a coder). I followed the tools' lead intentionally, curious to see what they had to offer. But in doing so, I slipped back into early-career patterns, prioritizing feature work and not handling code smells up front. I lost my Monday-ness. I'm a code whisperer. A wild west code wrangler. The one who could reshape entire systems by refactoring in their sleep. In this post, I want to return to the process that made that kind of work possible. The one that helped me grow from an intrepid puzzle-solver into a slayer of ye olde tech debt. It's not flashy. But it's deliberate, repeatable, and it's how I've quietly transformed codebases, again and again. The Core Philosophy Building software is a cycle of failing and learning. You'll never build spotless code, and can't fully predict the future. Whatever you did yesterday is wrong for today. That's why I treat building software as a conversation. All code talks back. It resists change, reveals design tensions, and asks for structure. A refactor-first, feature-last workflow gives me the space to listen before I act and lay the groundwork for successful feature building. The Workflow This diagram walks through all the stages I go through to develop a feature. You notice it has loops, sometimes I go through them a few times for any story I'm working on. Identify Feature Scope Usually, you do this before working on something, but it's a helpful starting point. Your feature might change scope or be broken into multiple features as you work. Attempt Loop I rarely do a feature in one shot. I take at least two passes through here, often 3 or 4. However, part of this process is that each subsequent iteration should be easier than the last. This loop has these stages: Try implementing the feature: The first iteration should be messy. See what you can do: see what you need. Evaluate friction and code smells: As you go, you'll get a sense of where the code isn't working and what you need to do for this feature. It might be missing test coverage, interface/abstraction, code duplication, or code smells. Keep a list of things you notice. You don't have to completely implement it before moving on; you just need to understand the space. Decide: Can I add this feature cleanly while touching as little existing code as possible? This question is my primary evaluation criterion for whether or not I can move on to feature development. I typically prioritize reducing the risk of human error. Human errors are reduced when I can: Cleanly add feature flags to toggle new behaviors on/off Implement new code in focused isolation from the existing system The SOLID principles are some of my primary benchmarks for evaluating this. These principles help me focus new work into smaller building blocks and help me find the missing ones. Branches: If your answer to the Decide question is: Yes: Sweet, go to the feature phase No: Go to the refactor phase. Throw away this attempt. Hard reset, delete the branch, or do whatever feels useful. Too Big: The feature scope is too big if you're having difficulty keeping track of all the parts. Go back and re-evaluate the feature scope. Refactor Phase For the refactoring phase, you'll go through the top 2-3 friction points you identified earlier. For each friction point: Create a new branch: do each refactoring in isolation. Isolating helps keep code reviews fast and simplifies identifying which introduced a defect in the worst-case scenario. Add/update tests: ensure good test coverage before making changes. Tests help protect against errors even when refactoring. For some things, if you aren't changing behavior, you might consider a compiler as test coverage. Refactor: make your changes Open a Pull Request, Code Review, Run Validation: Like any other code change, do your typical quality checks. If you kept it small, these should be quick. It's much easier to get a little bit of someone's time to review a small PR than it is to get them to review a big one. Once all the friction points you wanted to address are complete, return to the Feature Attempt Loop. Feature Phase By the time you get here, you've probably done most of the hard work. You should know how you want to build this feature, which should be relatively straightforward. Create a new branch: create the branch from your main branch with your completed refactoring. Implement your feature: write new code, add new tests Open a Pull Request, Code Review, Run Validation: Get feedback, but remember, it doesn't have to be perfect – you'll fix it next time. Approved: Mer

Two months into my no-code-writing development experiment, I've started to reflect on what I've gained and lost in the process.

There are clear wins: faster prototyping, more exploratory design conversations before touching code, and almost no actual coding (which is a huge relief, I'm more of an organize-ideas person, not a coder).

I followed the tools' lead intentionally, curious to see what they had to offer. But in doing so, I slipped back into early-career patterns, prioritizing feature work and not handling code smells up front. I lost my Monday-ness.

I'm a code whisperer. A wild west code wrangler. The one who could reshape entire systems by refactoring in their sleep.

In this post, I want to return to the process that made that kind of work possible. The one that helped me grow from an intrepid puzzle-solver into a slayer of ye olde tech debt. It's not flashy. But it's deliberate, repeatable, and it's how I've quietly transformed codebases, again and again.

The Core Philosophy

Building software is a cycle of failing and learning. You'll never build spotless code, and can't fully predict the future. Whatever you did yesterday is wrong for today.

That's why I treat building software as a conversation. All code talks back. It resists change, reveals design tensions, and asks for structure. A refactor-first, feature-last workflow gives me the space to listen before I act and lay the groundwork for successful feature building.

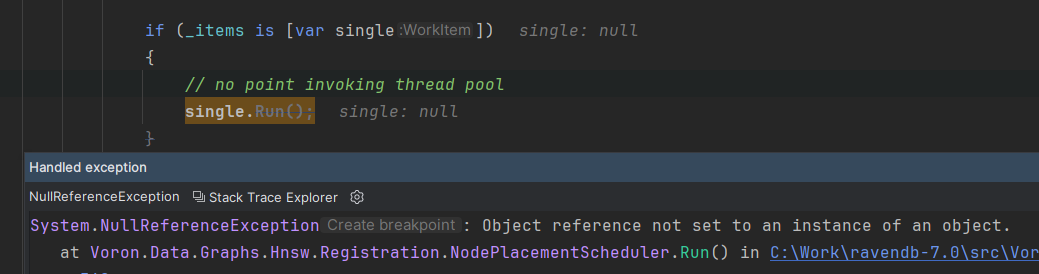

The Workflow

This diagram walks through all the stages I go through to develop a feature. You notice it has loops, sometimes I go through them a few times for any story I'm working on.

Identify Feature Scope

Usually, you do this before working on something, but it's a helpful starting point. Your feature might change scope or be broken into multiple features as you work.

Attempt Loop

I rarely do a feature in one shot. I take at least two passes through here, often 3 or 4. However, part of this process is that each subsequent iteration should be easier than the last. This loop has these stages:

- Try implementing the feature: The first iteration should be messy. See what you can do: see what you need.

- Evaluate friction and code smells: As you go, you'll get a sense of where the code isn't working and what you need to do for this feature. It might be missing test coverage, interface/abstraction, code duplication, or code smells. Keep a list of things you notice. You don't have to completely implement it before moving on; you just need to understand the space.

-

Decide: Can I add this feature cleanly while touching as little existing code as possible? This question is my primary evaluation criterion for whether or not I can move on to feature development. I typically prioritize reducing the risk of human error. Human errors are reduced when I can:

- Cleanly add feature flags to toggle new behaviors on/off

- Implement new code in focused isolation from the existing system

The SOLID principles are some of my primary benchmarks for evaluating this. These principles help me focus new work into smaller building blocks and help me find the missing ones.

-

Branches: If your answer to the Decide question is:

- Yes: Sweet, go to the feature phase

- No: Go to the refactor phase. Throw away this attempt. Hard reset, delete the branch, or do whatever feels useful.

- Too Big: The feature scope is too big if you're having difficulty keeping track of all the parts. Go back and re-evaluate the feature scope.

Refactor Phase

For the refactoring phase, you'll go through the top 2-3 friction points you identified earlier. For each friction point:

- Create a new branch: do each refactoring in isolation. Isolating helps keep code reviews fast and simplifies identifying which introduced a defect in the worst-case scenario.

- Add/update tests: ensure good test coverage before making changes. Tests help protect against errors even when refactoring. For some things, if you aren't changing behavior, you might consider a compiler as test coverage.

- Refactor: make your changes

- Open a Pull Request, Code Review, Run Validation: Like any other code change, do your typical quality checks. If you kept it small, these should be quick. It's much easier to get a little bit of someone's time to review a small PR than it is to get them to review a big one.

Once all the friction points you wanted to address are complete, return to the Feature Attempt Loop.

Feature Phase

By the time you get here, you've probably done most of the hard work. You should know how you want to build this feature, which should be relatively straightforward.

- Create a new branch: create the branch from your main branch with your completed refactoring.

- Implement your feature: write new code, add new tests

-

Open a Pull Request, Code Review, Run Validation: Get feedback, but remember, it doesn't have to be perfect – you'll fix it next time.

- Approved: Merge it; you're done!

- New Issues Found: go back to the refactor loop. You could keep this branch for rebasing or cherry picking from later.

- Too Big: Getting here and deciding your PR is too big is still possible. A big PR will be hard to review. Go back to the beginning and evaluate your feature scope.

Why This Works

This workflow helps adapt without fear. Because I know whatever I ship today, I've already built the space to improve it tomorrow. Learning, making mistakes, and improving are built into the workflow.

Each phase is relatively quick – I'll often do an attempt in the morning, do multiple refactorings in the afternoon, and then the feature the next day. Each PR reduces the cognitive load for you and your reviewers because you took the time to make small changes and set yourself up for success. Smaller PRs also increase your ability to be agile and react to new information as you go.

Paired with micro-commits, I have a safe and unstoppable workflow. I've used this flow to deep re-architect projects, migrations from old libraries to new, and for everyday feature work. It empowers me to continuously evaluate code change risk, build trust and design awareness with my teammates, and find strategies to ensure I'm providing a high-quality experience for customers.

Barriers to Adoption

I've seen a lot of developers struggle with adopting this pattern. Here are the top barriers:

- Initial slowdown: As with any process change, you slow down when you implement it. You have to be disciplined in following it until it becomes second nature.

- Pattern recognition: I've always relied on a gut feeling that not everyone has for detecting code smells. There is an art to writing good code that not everyone has. Code is communication, and not everyone is good at communicating. But it's a skill you can learn over time.

- External pressure: Even if you develop the muscle to do this pattern, external pressure to 'get things done' can still override what you know needs to be done. In my experience, this workflow is more resilient to external pressures because I can't do the feature until I'm ready to, but in a very early startup environment, I've fallen back into old habits (feature first, too big PRs, not throwing away code when I should)

Final Thoughts

This workflow is key to my fearlessness when facing even the oldest tech debt, and is flexible enough to carry me through any tech stack. It's freeing to orient my work around learning from my mistakes and the mistakes of the previous authors.

I wanted to reflect on this workflow because I'm considering how it can apply when the 'conversation' includes AI tools. Can this flow be used to improve AI coding outcomes? Could it help reduce the context needed for any individual task? LLMs can do these tasks, but current tools require prompting each step individually, which is exceptionally tedious.

Some of my upcoming experiments will attempt to automate this workflow using LLMs.

What about you? Have you tried adopting a similar workflow? How do you talk to code? What barriers have you faced in trying to improve your workflows?

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] Microsoft 365: 1-Year Subscription (Family/Up to 6 Users) (23% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![From Art School Drop-out to Microsoft Engineer with Shashi Lo [Podcast #170]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1746203291209/439bf16b-c820-4fe8-b69e-94d80533b2df.png?#)

![Re-designing a Git/development workflow with best practices [closed]](https://i.postimg.cc/tRvBYcrt/branching-example.jpg)

(1).jpg?#)

_Inge_Johnsson-Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![The Material 3 Expressive redesign of Google Clock leaks out [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/03/Google-Clock-v2.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![What Google Messages features are rolling out [May 2025]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/12/google-messages-name-cover.png?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![New Apple iPad mini 7 On Sale for $399! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96096/96096/96096-640.jpg)

![Apple to Split iPhone Launches Across Fall and Spring in Major Shakeup [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97211/97211/97211-640.jpg)

![Apple to Move Camera to Top Left, Hide Face ID Under Display in iPhone 18 Pro Redesign [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97212/97212/97212-640.jpg)

![Apple Developing Battery Case for iPhone 17 Air Amid Battery Life Concerns [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97208/97208/97208-640.jpg)