A once-abandoned parking garage in Buenos Aires is now a stunning tower with a park on top

Four years ago, if you found yourself at one particular intersection of Buenos Aires, you would see a nondescript, three-story parking garage with no cars inside. That building still exists—but it’s completely unrecognizable. Today, that structure looks like a stubby, UFO-like tower mushrooming from a concrete pedestal with a landscaped ramp curving upward. The metamorphosis is thanks to a multiyear project by New York architecture firm ODA. Ola Palermo, as the reimagined structure is known, has become a mixed-use building with cafés, restaurants, and Class A office space. The cherry on top of this (concrete) cake is an open-air promenade that peels off the sidewalk, winds up to what used to be the roof of the garage, blossoms into a rooftop park, then winds back down to the other side of the building. In a structure once defined by cars, the ramp is now be synonymous with people.[Photo: Alan Karchmer/courtesy ODA]To demolish or not to demolishODA (ranked among the World’s Most Innovative Companies of 2025 by Fast Company) has a history of working on adaptive reuse projects, including Detroit’s Book Tower and 10 Jay Street in Brooklyn, but when founder Eran Chen first heard about the project from real estate firm BSD Investments, it was presented to him as an empty site.The building, which had been vacant for years, sits on a tricky plot sandwiched between two busy roads and an elevated train line. It is very close to the edge of Tres de Febrero Park (also known as Bosques de Palermo, or Palermo Woods), but before ODA got involved the two were not connected. [Image: courtesy ODA]Before arriving on-site, Chen had considered demolishing the parking garage, but when he saw the building, the idea just clicked. “The building immediately captured my imagination,” Chen says, noting the first thing that surprised him was the structure’s ceiling height. Most parking garages have low ceilings, which makes them challenging to convert—this one had a 14- to 15-foot ceiling. (For perspective: Most homes have 8- to 9-foot ceilings.) The ceiling had a waffle design, which looks like a grid of intersecting beams that create a pattern of recessed squares. This helped distribute the weight of the ceiling evenly, allowing it to span large areas without the need for additional columns for support, and creating a more open and flexible space for the building’s use. [Photo: Alan Karchmer/courtesy ODA]To top it all off, the roof afforded a clear 360-degree view. On one side, you could see through Palermo Woods, all the way to downtown Buenos Aires. On the other, there’s a private racetrack and polo fields that people can visit only if they have exclusive memberships. “On one side you have the haves, and on the other, you have everybody else, and this is smack dab in between the two,” says Chen. He saw the rooftop as an opportunity to turn the tables and allow the park’s visitors to “look down” on the exclusive grounds and catch a (free) glimpse of any events that take place there.[Photo: Alan Karchmer/courtesy ODA]Form follows experiencesODA kept 80% of the original structure to create a 160,000-square-foot building. A quarter of this surface—about 40,000 square feet—is dedicated to public terraces, green spaces, and the open-air promenade. The rest is taken up by restaurants, cafés, and retail spaces. Parking for 250 cars is also available on the ground floor. But the program, or function, of the building wasn’t always clear. The area isn’t zoned for residential use, and commercial use wasn’t “the obvious choice,” says Chen, as most companies who could afford rent for a modern office building would opt for a space in downtown Buenos Aires. Retail, which thrives on heavy footfall, wasn’t obvious either since the site is so isolated and on the edge of the city.[Photo: Alan Karchmer/courtesy ODA]But for many years now, Chen has been honing a new mantra. “Form should not follow function anymore. Form should follow experiences,” he says. “If we design buildings for the human experience, people will visit these buildings—and enjoy them—regardless of the program.” In other words, build it and they will come? I ask. “Build it well and they will come,” he says. An important distinction. To turn the building into an irresistible destination, ODA made four incisions. They carved out one courtyard to let light into the widest part of the building, and shaved off slivers of the facade to make room for two sets of stairs and the ramp.These incisions amount to 20% of the floor area, but the architects didn’t lose that space; they redistributed it. At one end of the building, there once was a water tower that rose above the area’s height restrictions. The tower was obsolete, so Chen convinced the city to remove it. In its place, Chen’s team built a four-story tower “based on the memory of the water tower.” This “concrete mushroom” as he calls it, now rises above the rest of the structure, holding its most premium office spaces.[Photo: Alan Karc

Four years ago, if you found yourself at one particular intersection of Buenos Aires, you would see a nondescript, three-story parking garage with no cars inside. That building still exists—but it’s completely unrecognizable.

Today, that structure looks like a stubby, UFO-like tower mushrooming from a concrete pedestal with a landscaped ramp curving upward. The metamorphosis is thanks to a multiyear project by New York architecture firm ODA.

Ola Palermo, as the reimagined structure is known, has become a mixed-use building with cafés, restaurants, and Class A office space. The cherry on top of this (concrete) cake is an open-air promenade that peels off the sidewalk, winds up to what used to be the roof of the garage, blossoms into a rooftop park, then winds back down to the other side of the building. In a structure once defined by cars, the ramp is now be synonymous with people.

To demolish or not to demolish

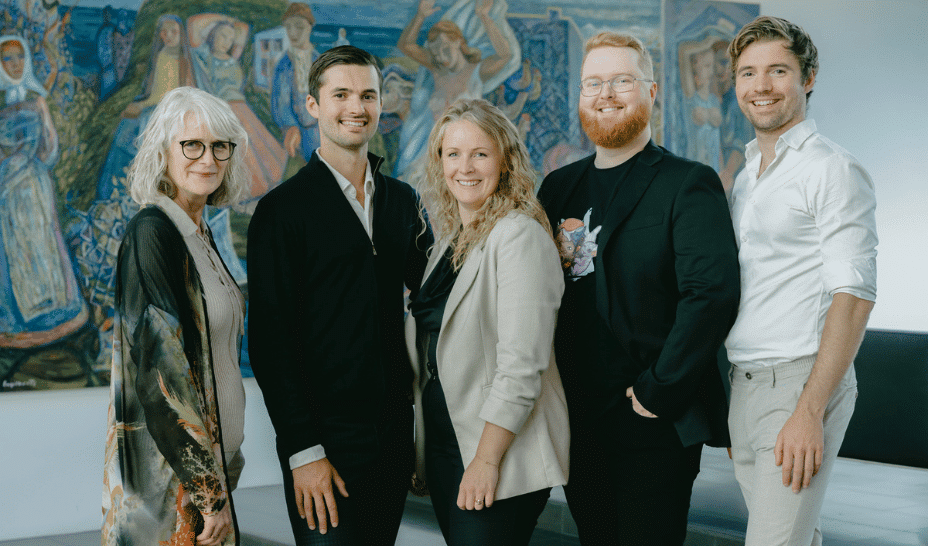

ODA (ranked among the World’s Most Innovative Companies of 2025 by Fast Company) has a history of working on adaptive reuse projects, including Detroit’s Book Tower and 10 Jay Street in Brooklyn, but when founder Eran Chen first heard about the project from real estate firm BSD Investments, it was presented to him as an empty site.

The building, which had been vacant for years, sits on a tricky plot sandwiched between two busy roads and an elevated train line. It is very close to the edge of Tres de Febrero Park (also known as Bosques de Palermo, or Palermo Woods), but before ODA got involved the two were not connected.

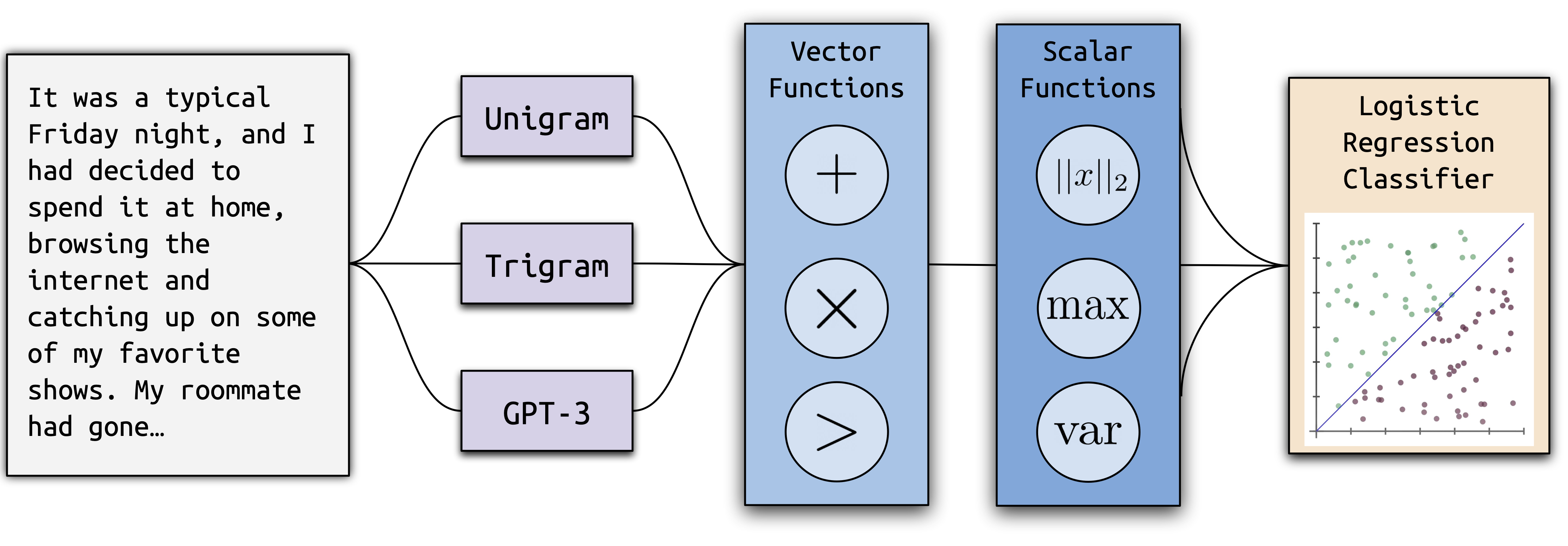

Before arriving on-site, Chen had considered demolishing the parking garage, but when he saw the building, the idea just clicked. “The building immediately captured my imagination,” Chen says, noting the first thing that surprised him was the structure’s ceiling height. Most parking garages have low ceilings, which makes them challenging to convert—this one had a 14- to 15-foot ceiling. (For perspective: Most homes have 8- to 9-foot ceilings.)

The ceiling had a waffle design, which looks like a grid of intersecting beams that create a pattern of recessed squares. This helped distribute the weight of the ceiling evenly, allowing it to span large areas without the need for additional columns for support, and creating a more open and flexible space for the building’s use.

To top it all off, the roof afforded a clear 360-degree view. On one side, you could see through Palermo Woods, all the way to downtown Buenos Aires. On the other, there’s a private racetrack and polo fields that people can visit only if they have exclusive memberships. “On one side you have the haves, and on the other, you have everybody else, and this is smack dab in between the two,” says Chen.

He saw the rooftop as an opportunity to turn the tables and allow the park’s visitors to “look down” on the exclusive grounds and catch a (free) glimpse of any events that take place there.

Form follows experiences

ODA kept 80% of the original structure to create a 160,000-square-foot building. A quarter of this surface—about 40,000 square feet—is dedicated to public terraces, green spaces, and the open-air promenade. The rest is taken up by restaurants, cafés, and retail spaces. Parking for 250 cars is also available on the ground floor.

But the program, or function, of the building wasn’t always clear. The area isn’t zoned for residential use, and commercial use wasn’t “the obvious choice,” says Chen, as most companies who could afford rent for a modern office building would opt for a space in downtown Buenos Aires. Retail, which thrives on heavy footfall, wasn’t obvious either since the site is so isolated and on the edge of the city.

But for many years now, Chen has been honing a new mantra. “Form should not follow function anymore. Form should follow experiences,” he says. “If we design buildings for the human experience, people will visit these buildings—and enjoy them—regardless of the program.”

In other words, build it and they will come? I ask. “Build it well and they will come,” he says. An important distinction.

To turn the building into an irresistible destination, ODA made four incisions. They carved out one courtyard to let light into the widest part of the building, and shaved off slivers of the facade to make room for two sets of stairs and the ramp.

These incisions amount to 20% of the floor area, but the architects didn’t lose that space; they redistributed it. At one end of the building, there once was a water tower that rose above the area’s height restrictions. The tower was obsolete, so Chen convinced the city to remove it. In its place, Chen’s team built a four-story tower “based on the memory of the water tower.” This “concrete mushroom” as he calls it, now rises above the rest of the structure, holding its most premium office spaces.

A blueprint for the U.S.

The resulting building is what Chen calls a “win-win-win.” It benefits city agencies because it makes a meaningful contribution to the public realm. It benefits the local community, which now has access to a public rooftop park. And it benefits the developer, who saved on construction costs (no new foundations were required) by not demolishing the building.

It also benefits the environment, since giving buildings a second chance, as Chen puts it, can help lower the environmental footprint associated with building anew. (Though there could be costs associated with bringing an old building up to code.)

“Cities are filled with structures that are either dated or unnecessary, and of course, a big chunk of it is parking garages,” Chen says.

Already, architects are starting to build “future-proof” parking garages like this multistory car park in Calgary, Alberta, that was specifically designed to transform into a 600-person office or 50-unit residential building if (and when) the need arises.

But Chen believes that residential and commercial are not the only options, especially if the building’s ceilings are low, as they often are. He includes indoor/outdoor sports venues, like pickleball courts; urban farms; and even open-air markets among the possibilities. “The key,” he says, “is not to be fixated on the obvious programs that people might think of.”

![[The AI Show Episode 142]: ChatGPT’s New Image Generator, Studio Ghibli Craze and Backlash, Gemini 2.5, OpenAI Academy, 4o Updates, Vibe Marketing & xAI Acquires X](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20142%20cover.png)

![YouTube Announces New Creation Tools for Shorts [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96923/96923/96923-640.jpg)

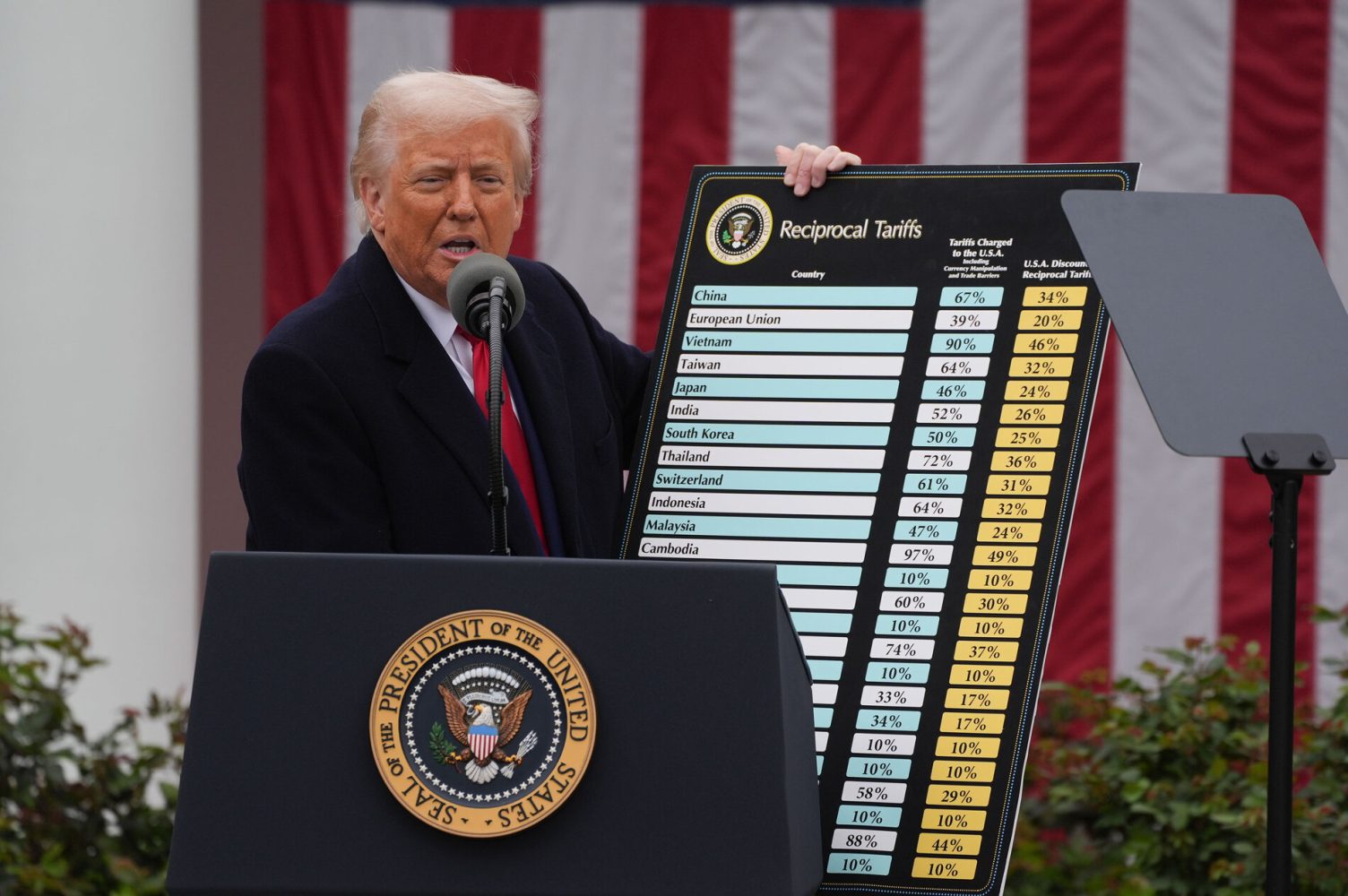

![Apple Faces New Tariffs but Has Options to Soften the Blow [Kuo]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96921/96921/96921-640.jpg)