6 forgotten heroes of mid-century Modern design you need to know

The Postwar design phenomenon known as mid-century modernism has been back—and thriving—for years now. In addition to a steady stream of new products from major retailers that cash in on the clean curves of the past, people continue to buy originals, reissues, and knockoffs of icons like the Eames Lounge Chair in droves. But if there’s one person I’d wager loves it just a bit more than the rest of us, it’s journalist Dominic Bradbury. In the wake of his tomes Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces and Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses, today Bradbury is back with another book: Mid-Century Modern Designers, a hulking A to Z chronicle of 300 design pioneers known and unknown. [Photo: courtesy Phaidon] “I do write about contemporary design and contemporary architecture as well,” Bradbury says. “But I have become slightly obsessive and fixated on this period. I just find it so exciting and so inspiring in lots of different ways.” Naturally, it was thus more difficult for Bradbury to stop at 300 designers than it was for him to reach 300 in the first place. His initial list comprised some 450–500 names, and he whittled it down using a number of criteria. He and the publisher wanted an international focus and a diversity of disciplines, with a particular focus on those designing for home or personal use. They also wanted a mix of big names like the Eameses, Alvar Aalto, and Lina Bo Bardi, as well as more obscure designers who played a critical role in the movement. “What I find really exciting about doing these kind of big, research-led books, is you’ll always discover something new,” Bradbury says of resurfacing lesser-known talents. To that end, on the eve of the book’s publication, we asked Bradbury to select his top five forgotten mid-century Moderns who helped define their era. Their work speaks to the question of who gets remembered and who gets left in the past—and perhaps also shines a light on why the world still can’t seem to get enough mid-century modernism at large. “It’s such an extraordinary period of innovation and excitement and so many ideas—and just also this really incredibly optimistic feeling, which I think we’re probably all in need of at the moment,” says Bradbury. Yrjo Kukkapuro [Photo: courtesy Phaidon] Yrjö Kukkapuro (1933–2025) The Finnish Kukkapuro used to sit in the snow to study the shape of the human body as he was working on his best-known piece, the 1964 Karuselli (carousel) Chair, according to Bradbury. Kukkapuro later covered himself in chicken wire to create a plaster mold of himself reclining, all of which played into the final design of the reclining swivel chair. “He was one of the early masters of ergonomics,” Bradbury notes. The chair found fame when it landed on the cover of architectural and design magazine Domus in 1966. Its production continues to this day, although Kukkapuro is often overlooked in lieu of more famous Finnish designers, such as Alvar Aalto. “When you’re going around Scandinavia, you sometimes see these chairs in hotel lobbies and things like that,” Bradbury says. “They’ve become a bit of an icon.” Nanna Ditzel [Photo: courtesy Phaidon] Nanna Ditzel (1923–2005) You may not know the Danish Ditzel by name, but you’ve probably seen her most famous work—or copies of it—which she designed with her husband, Jørgen Ditzel: the 1957 Hanging Egg Chair. It is also still in production today, like many of her creations. “I really admire her for her combination of craftsmanship and organic materiality,” Bradbury says, adding that while other egg chairs of the period might have been created using fiberglass or other solutions, the Ditzels used natural wicker—spinning an expressive take on traditional materials in a modern context. Thanks to such decisions, as Bradbury notes in his book, Ditzel offered “an engaging version of warm Modernism.” While Ditzel may not be mentioned in the same breath as other master Midcentury Scandinavian designers, Bradbury says that like many on this list, her work is being rediscovered as people search archives for pieces that could be suitable for reissue or collection today. Borge Mogensen [Photo: courtesy Phaidon] Børge Mogensen (1914-1972) Mogensen trained under Kaare Klint, “the father of modern Danish furniture design.” Bradbury says a major part of Klint’s approach was making sure one understood tradition—and that carried over to his protégé’s output. “Mogensen’s work [features] this combination of looking to the past and looking to the future at the same time,” says Bradbury. “So he would take traditional forms of furniture, like a hunting chair, and then reinterpret them in this sort of modern idiom.” That yielded such pieces as the 1950 Hunting Chair and his 1958 Spanish Chair—creations that make one ponder the broader question of why some designers get overlooked in mid-century modern history at large. Bradbury says one key part of the equation is

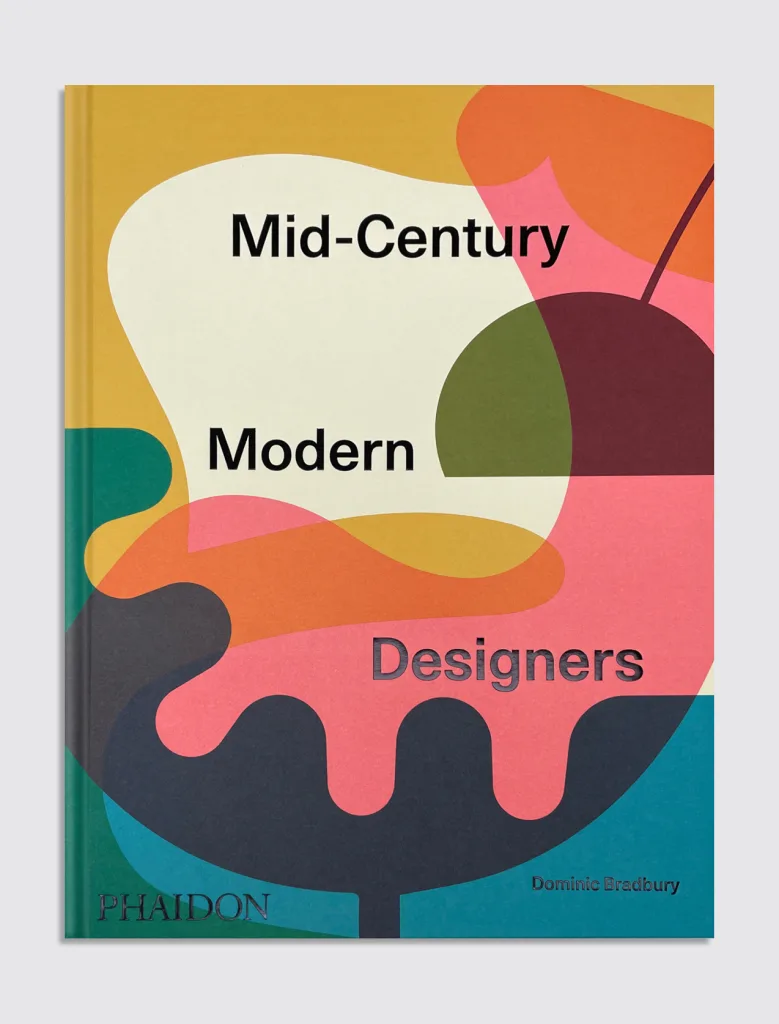

The Postwar design phenomenon known as mid-century modernism has been back—and thriving—for years now. In addition to a steady stream of new products from major retailers that cash in on the clean curves of the past, people continue to buy originals, reissues, and knockoffs of icons like the Eames Lounge Chair in droves.

But if there’s one person I’d wager loves it just a bit more than the rest of us, it’s journalist Dominic Bradbury. In the wake of his tomes Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces and Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses, today Bradbury is back with another book: Mid-Century Modern Designers, a hulking A to Z chronicle of 300 design pioneers known and unknown.

“I do write about contemporary design and contemporary architecture as well,” Bradbury says. “But I have become slightly obsessive and fixated on this period. I just find it so exciting and so inspiring in lots of different ways.”

Naturally, it was thus more difficult for Bradbury to stop at 300 designers than it was for him to reach 300 in the first place. His initial list comprised some 450–500 names, and he whittled it down using a number of criteria.

He and the publisher wanted an international focus and a diversity of disciplines, with a particular focus on those designing for home or personal use. They also wanted a mix of big names like the Eameses, Alvar Aalto, and Lina Bo Bardi, as well as more obscure designers who played a critical role in the movement. “What I find really exciting about doing these kind of big, research-led books, is you’ll always discover something new,” Bradbury says of resurfacing lesser-known talents.

To that end, on the eve of the book’s publication, we asked Bradbury to select his top five forgotten mid-century Moderns who helped define their era. Their work speaks to the question of who gets remembered and who gets left in the past—and perhaps also shines a light on why the world still can’t seem to get enough mid-century modernism at large.

“It’s such an extraordinary period of innovation and excitement and so many ideas—and just also this really incredibly optimistic feeling, which I think we’re probably all in need of at the moment,” says Bradbury.

Yrjö Kukkapuro (1933–2025)

The Finnish Kukkapuro used to sit in the snow to study the shape of the human body as he was working on his best-known piece, the 1964 Karuselli (carousel) Chair, according to Bradbury. Kukkapuro later covered himself in chicken wire to create a plaster mold of himself reclining, all of which played into the final design of the reclining swivel chair.

“He was one of the early masters of ergonomics,” Bradbury notes.

The chair found fame when it landed on the cover of architectural and design magazine Domus in 1966. Its production continues to this day, although Kukkapuro is often overlooked in lieu of more famous Finnish designers, such as Alvar Aalto.

“When you’re going around Scandinavia, you sometimes see these chairs in hotel lobbies and things like that,” Bradbury says. “They’ve become a bit of an icon.”

Nanna Ditzel (1923–2005)

You may not know the Danish Ditzel by name, but you’ve probably seen her most famous work—or copies of it—which she designed with her husband, Jørgen Ditzel: the 1957 Hanging Egg Chair. It is also still in production today, like many of her creations.

“I really admire her for her combination of craftsmanship and organic materiality,” Bradbury says, adding that while other egg chairs of the period might have been created using fiberglass or other solutions, the Ditzels used natural wicker—spinning an expressive take on traditional materials in a modern context. Thanks to such decisions, as Bradbury notes in his book, Ditzel offered “an engaging version of warm Modernism.”

While Ditzel may not be mentioned in the same breath as other master Midcentury Scandinavian designers, Bradbury says that like many on this list, her work is being rediscovered as people search archives for pieces that could be suitable for reissue or collection today.

Børge Mogensen (1914-1972)

Mogensen trained under Kaare Klint, “the father of modern Danish furniture design.” Bradbury says a major part of Klint’s approach was making sure one understood tradition—and that carried over to his protégé’s output.

“Mogensen’s work [features] this combination of looking to the past and looking to the future at the same time,” says Bradbury. “So he would take traditional forms of furniture, like a hunting chair, and then reinterpret them in this sort of modern idiom.”

That yielded such pieces as the 1950 Hunting Chair and his 1958 Spanish Chair—creations that make one ponder the broader question of why some designers get overlooked in mid-century modern history at large. Bradbury says one key part of the equation is whether or not a designer’s work took off internationally—like, say, Finn Juhl’s did in the U.S. and Asia.

Another major factor Bradbury is mulling at the moment: How designers were (or were not) embraced by the media, and how they promoted themselves. (“The mid-century era is kind of when that started becoming more and more important,” he says.) He says the Scandinavians were adept at it, and they would band together to do shows and exhibitions to get eyes on their work—and as a result, many left a lasting impression in mid-century Modernism to this day.

This contradicts the British mid-century modern designers below.

John & Sylvia Reid (1925–1992; 1924–2022)

While many mid-century modernists are known for their high-end output, the married Reids became ubiquitous for their lower-priced furniture designs from the U.K. stalwart Stag Furniture. The Reids’ bedroom collections targeted young couples, who could buy a set or a piece at a time.

“They were very popular lines in the U.K. during the Postwar period,” Bradbury says. “Their furniture was beautifully designed, well-made, but quite affordable.”

Like Charles and Ray Eames, they weren’t limited to furniture, and were wildly talented multidisciplinary designers who also worked in lighting and graphic design. Unlike the Eameses, they didn’t receive an enduring acclaim that persists to this day.

Sergio Rodrigues (1927–2014)

Bradbury started to notice a pattern when working on his book New Brazilian House.

“We just kept seeing these amazing pieces of furniture—beautiful mid-century chairs with wooden frames and kind of slouchy leather cushions. We’d say, who designed those? And [the answer] would be Sergio Rodrigues,” he recalls.

As Bradbury details in his new book, Rodrigues created his signature Mole Armchair in 1957 after photographer Otto Stupakoff asked him to create a comfy couch for him. He later had another hit in 2002 with the Diz Lounge Armchair; a culmination of a long career.

“There was something quite joyful about his work—you just wanted to relax into his armchairs or his sofas,” says Bradbury. “They’re the kind of chair you can’t walk past without wanting to sit yourself down and spend a moment.”

Ultimately, Rodrigues’s work was spotted and appeared in international trade shows, leading to distribution abroad. But what of the other South American mid-century modernists lost to time?

“[They] just sort of stayed at home and concentrated on [their] home market—but that doesn’t mean the work is any less amazing,” Bradbury says.

Who knows: In the current era of mid-century rediscovery and reappreciation, it may only be a matter of time before we see these mid-century modern designers anew, as well.

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

.jpg?#)

.png?#)

-Baldur’s-Gate-3-The-Final-Patch---An-Animated-Short-00-03-43.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Aleksey_Funtap_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![‘Samsung Auto’ is an Android Auto alternative for Galaxy phones you can’t use [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/04/samsung-auto-12.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Taps Samsung as Exclusive OLED Supplier for Foldable iPhone [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97020/97020/97020-640.jpg)

![Apple's Foldable iPhone Won't Have Face ID for Under-Display Camera [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97017/97017/97017-640.jpg)