Introduction to Data Engineering Concepts |6| Data Modeling Basics

Free Resources Free Apache Iceberg Course Free Copy of “Apache Iceberg: The Definitive Guide” Free Copy of “Apache Polaris: The Definitive Guide” 2025 Apache Iceberg Architecture Guide How to Join the Iceberg Community Iceberg Lakehouse Engineering Video Playlist Ultimate Apache Iceberg Resource Guide Behind every useful dashboard or analytics report lies a well-structured data model. Data modeling is the practice of shaping data into organized structures that are easy to query, analyze, and maintain. While it may sound abstract, modeling directly impacts how quickly and accurately data consumers can extract value from the information stored in your systems. In this post, we’ll look at the foundations of data modeling, the difference between OLTP and OLAP systems, and common schema designs that data engineers use to build efficient and scalable data platforms. Why Data Modeling Matters When data arrives from source systems, it’s often raw and optimized for transactions, not analysis. A transactional database might record every sale or click in granular detail, but that structure doesn’t translate well into aggregations like “monthly revenue by product category.” A data model reshapes that data to make it usable. Good models reduce complexity, improve performance, and minimize errors. Poor models, on the other hand, lead to slow queries, redundant data, and confusion about what numbers really mean. Modeling is both a technical and a collaborative process. It requires not just understanding how data is structured, but also how the business thinks about that data—what questions need answering, how metrics are defined, and what trade-offs are acceptable. OLTP vs OLAP: Two Worlds, Two Purposes Before diving into specific modeling techniques, it’s important to distinguish between the two main types of data systems: OLTP and OLAP. OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) systems are built for real-time operations. Think of point-of-sale systems, user authentication services, or banking apps. These systems are optimized for high-throughput reads and writes, handling thousands of small transactions per second. Their schemas are typically highly normalized to avoid data duplication and to keep updates fast and consistent. OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) systems, on the other hand, are designed for analysis. These platforms support complex queries over large volumes of historical data. Performance here is about aggregating, filtering, and summarizing—not handling rapid transactions. Because of this, OLAP models often trade strict normalization for faster access to pre-joined or denormalized data. Understanding whether your system is OLTP or OLAP helps determine how you model your data. The techniques and trade-offs are different depending on the system’s purpose. Normalization and Denormalization In OLTP systems, normalization is the standard. This means structuring data so that each fact is stored in exactly one place. For example, instead of storing a customer’s name with every order record, you keep customer details in a separate table and reference them via a key. This approach minimizes redundancy, reduces storage, and simplifies updates. Change the customer’s name in one place, and every order reflects that change immediately. In analytical systems, this level of indirection becomes a performance bottleneck. Complex queries must join many tables together, which can slow things down significantly. That’s where denormalization comes in. In OLAP models, it’s common to store data in a flattened format, with descriptive attributes repeated across rows. While this increases storage requirements, it significantly speeds up query performance and simplifies logic for analysts and BI tools. Star and Snowflake Schemas Two common modeling patterns in OLAP systems are the star schema and the snowflake schema. A star schema organizes data around a central fact table. This table holds measurable events—like sales transactions—with keys that reference surrounding dimension tables, which contain descriptive attributes such as product names, customer demographics, or store locations. In a star schema, the dimension tables are typically denormalized. This makes queries straightforward and fast: one central join connects the fact table to all the attributes needed for analysis. The snowflake schema takes this idea further by normalizing the dimension tables. Instead of a single product dimension table, for example, you might have separate tables for product, category, and supplier. This saves space and can improve maintainability, but at the cost of more complex joins. The choice between star and snowflake schemas depends on your performance needs, data volume, and how often attributes change. Modeling for Flexibility and Growth Good data models are designed with change in mind. New columns will be added, relationships will evolve,

Free Resources

- Free Apache Iceberg Course

- Free Copy of “Apache Iceberg: The Definitive Guide”

- Free Copy of “Apache Polaris: The Definitive Guide”

- 2025 Apache Iceberg Architecture Guide

- How to Join the Iceberg Community

- Iceberg Lakehouse Engineering Video Playlist

- Ultimate Apache Iceberg Resource Guide

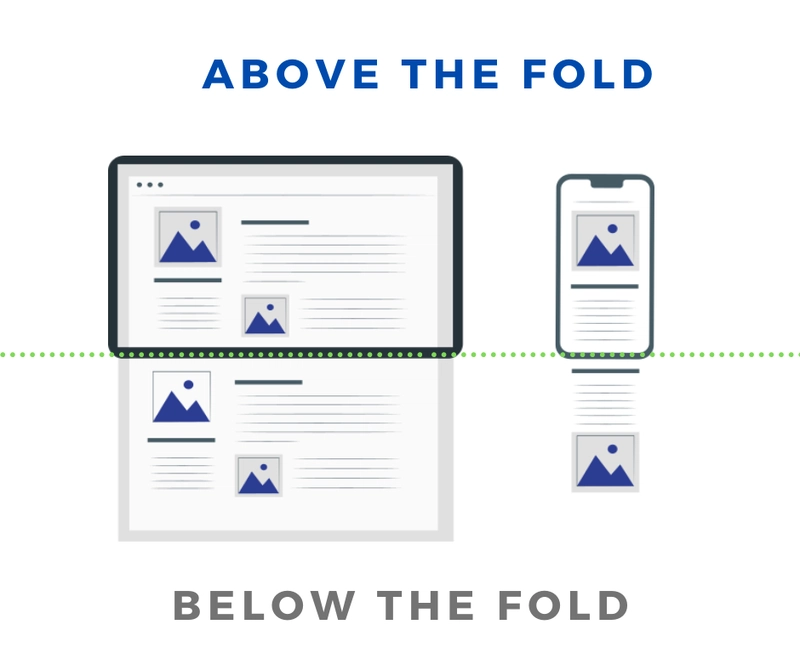

Behind every useful dashboard or analytics report lies a well-structured data model. Data modeling is the practice of shaping data into organized structures that are easy to query, analyze, and maintain. While it may sound abstract, modeling directly impacts how quickly and accurately data consumers can extract value from the information stored in your systems.

In this post, we’ll look at the foundations of data modeling, the difference between OLTP and OLAP systems, and common schema designs that data engineers use to build efficient and scalable data platforms.

Why Data Modeling Matters

When data arrives from source systems, it’s often raw and optimized for transactions, not analysis. A transactional database might record every sale or click in granular detail, but that structure doesn’t translate well into aggregations like “monthly revenue by product category.”

A data model reshapes that data to make it usable. Good models reduce complexity, improve performance, and minimize errors. Poor models, on the other hand, lead to slow queries, redundant data, and confusion about what numbers really mean.

Modeling is both a technical and a collaborative process. It requires not just understanding how data is structured, but also how the business thinks about that data—what questions need answering, how metrics are defined, and what trade-offs are acceptable.

OLTP vs OLAP: Two Worlds, Two Purposes

Before diving into specific modeling techniques, it’s important to distinguish between the two main types of data systems: OLTP and OLAP.

OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) systems are built for real-time operations. Think of point-of-sale systems, user authentication services, or banking apps. These systems are optimized for high-throughput reads and writes, handling thousands of small transactions per second. Their schemas are typically highly normalized to avoid data duplication and to keep updates fast and consistent.

OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) systems, on the other hand, are designed for analysis. These platforms support complex queries over large volumes of historical data. Performance here is about aggregating, filtering, and summarizing—not handling rapid transactions. Because of this, OLAP models often trade strict normalization for faster access to pre-joined or denormalized data.

Understanding whether your system is OLTP or OLAP helps determine how you model your data. The techniques and trade-offs are different depending on the system’s purpose.

Normalization and Denormalization

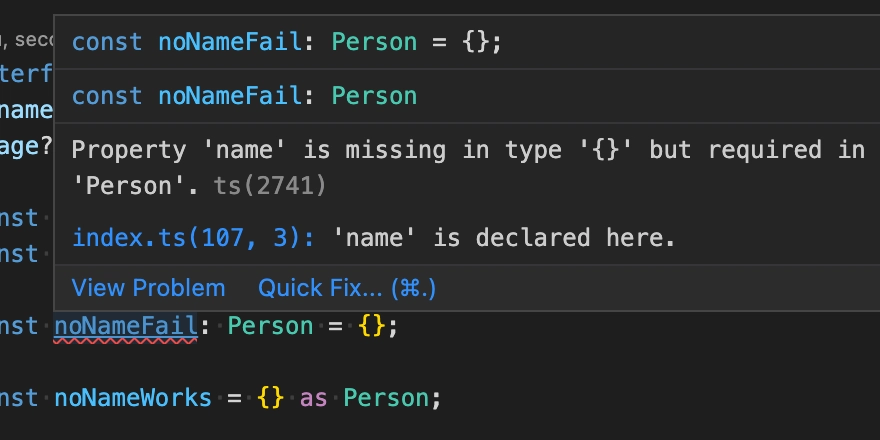

In OLTP systems, normalization is the standard. This means structuring data so that each fact is stored in exactly one place. For example, instead of storing a customer’s name with every order record, you keep customer details in a separate table and reference them via a key.

This approach minimizes redundancy, reduces storage, and simplifies updates. Change the customer’s name in one place, and every order reflects that change immediately.

In analytical systems, this level of indirection becomes a performance bottleneck. Complex queries must join many tables together, which can slow things down significantly.

That’s where denormalization comes in. In OLAP models, it’s common to store data in a flattened format, with descriptive attributes repeated across rows. While this increases storage requirements, it significantly speeds up query performance and simplifies logic for analysts and BI tools.

Star and Snowflake Schemas

Two common modeling patterns in OLAP systems are the star schema and the snowflake schema.

A star schema organizes data around a central fact table. This table holds measurable events—like sales transactions—with keys that reference surrounding dimension tables, which contain descriptive attributes such as product names, customer demographics, or store locations.

In a star schema, the dimension tables are typically denormalized. This makes queries straightforward and fast: one central join connects the fact table to all the attributes needed for analysis.

The snowflake schema takes this idea further by normalizing the dimension tables. Instead of a single product dimension table, for example, you might have separate tables for product, category, and supplier. This saves space and can improve maintainability, but at the cost of more complex joins.

The choice between star and snowflake schemas depends on your performance needs, data volume, and how often attributes change.

Modeling for Flexibility and Growth

Good data models are designed with change in mind. New columns will be added, relationships will evolve, and new metrics will be needed. A rigid model can become a bottleneck, while a flexible one supports ongoing development.

One best practice is to favor additive metrics when possible. These are measures you can safely sum across time or groups—like revenue or quantity sold. Additive metrics work better with aggregations and are easier to model consistently.

It’s also important to consider slowly changing dimensions. For example, if a customer’s email address or a product’s price changes, do you want to reflect the latest value, or keep historical versions? Modeling for this kind of change requires thought about versioning and historical accuracy.

The Road Ahead

Data modeling sits at the intersection of technical design and business logic. It’s not just about tables and keys—it’s about making data intuitive and useful for the people who depend on it.

As data engineers, our role is to create models that strike a balance between performance, maintainability, and expressiveness. Doing this well requires not just technical skill, but ongoing communication with analysts, stakeholders, and subject matter experts.

In the next post, we’ll take a closer look at data warehousing—how these models are stored, queried, and optimized in systems built for analytics at scale.

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![[FREE EBOOKS] Learn Computer Forensics — 2nd edition, AI and Business Rule Engines for Excel Power Users & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![From Art School Drop-out to Microsoft Engineer with Shashi Lo [Podcast #170]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1746203291209/439bf16b-c820-4fe8-b69e-94d80533b2df.png?#)

(1).jpg?#)

![Apple to Split iPhone Launches Across Fall and Spring in Major Shakeup [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97211/97211/97211-640.jpg)

![Apple to Move Camera to Top Left, Hide Face ID Under Display in iPhone 18 Pro Redesign [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97212/97212/97212-640.jpg)

_Inge_Johnsson-Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Apple Developing Battery Case for iPhone 17 Air Amid Battery Life Concerns [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97208/97208/97208-640.jpg)

![AirPods 4 On Sale for $99 [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97206/97206/97206-640.jpg)