How to Implement Serializable Snapshot Isolation for Transactions

Introduction This article will start with the basic concepts of transactions, introduce the various problems faced by concurrent transactions along with their corresponding solutions, and provide a detailed explanation and analysis of Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI), including its concept and implementation. Basic Concepts A transaction in a database is a way to group multiple read and write operations into a single logical unit. A transaction either commits successfully or aborts (or rolls back). This characteristic of transactions greatly simplifies the issues that application developers need to consider when interacting with a database (e.g., partial failures). The safety guarantees provided by transactions are commonly described by the ACID properties: Atomicity Consistency Isolation Durability We will focus on the implementation of Isolation, which describes the behavior of a database when handling concurrent transactions. In the case of concurrent transactions, the database faces problems such as dirty reads, dirty writes, and nonrepeatable reads. To address these issues, different transaction isolation levels provide corresponding guarantees. Dirty Read: A transaction reads modifications made by another concurrent, uncommitted transaction. Dirty Write: A transaction's modifications overwrite changes made by another concurrent, uncommitted transaction. Read Skew (Nonrepeatable Read): Reading the same value at different times within a transaction yields different results. Lost Update: When concurrent transactions modify the same record, the changes made by the earlier (committed) transaction might be lost, as the later transaction overwrites them. Write Skew: Two concurrent transactions read the same data and update different records based on that data, ultimately violating the expected consistency constraints. Phantom Read: A transaction’s writes change the result set of a range query executed by another transaction. Dirty Write refers to a transaction overwriting modifications made by another uncommitted transaction. Lost Update occurs when concurrent transactions read the same object and then update the same object based on stale data, causing updates to be lost. Write Skew happens when concurrent transactions read the same data under specific conditions and then update different objects based on those reads. Although these updates do not conflict directly, they may violate business constraints. Snapshot Isolation To address nonrepeatable reads or read skew, we can use Snapshot Isolation (SI). As the name suggests, snapshot isolation means that the visibility scope of a transaction is a consistent snapshot of the database taken at the start of the transaction. During the lifetime of the transaction, modifications made by other concurrent transactions are not visible. Snapshot isolation is usually implemented in conjunction with MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control) because different transactions need to see the state of the database at different points in time, which requires maintaining multiple versions of the data. In MySQL’s InnoDB storage engine, each transaction is assigned a monotonically increasing unique transaction ID (transaction id) based on its creation time. To implement MVCC, each data row in the database maintains multiple versions (managed through undo logs), and each version is tagged with the transaction id of the transaction that created it. To determine which versions of the data are visible to the current transaction and which are not, InnoDB constructs a consistent view (read view) when the transaction is created. The consistent view contains four important fields: trx_ids: A list of IDs for all uncommitted transactions at the time the view was constructed. up_limit_id: The smallest transaction ID in trx_ids. All transaction IDs smaller than this value are considered committed. low_limit_id: The next transaction ID that has not yet been assigned at the time the Read View was created. creator_trx_id: The transaction ID of the transaction that created this consistent view. We can visualize this consistent view as follows: Transaction IDs greater than or equal to up_limit_id do not necessarily mean that those transactions have not committed. up_limit_id only guarantees that all transaction IDs smaller than it have committed, but it does not imply that all IDs greater than or equal to it are uncommitted. With this view, we can determine the visibility of each data row version to the current transaction by comparing the row’s transaction id with the fields of the read view: If the transaction id falls in the green area (txn_id < up_limit_id), the data version was created by a committed transaction and is visible. If the transaction id falls in the red area (txn_id >= low_limit_id), the data version was created by a transaction that has not yet started and is not visible. If the transaction id falls i

Introduction

This article will start with the basic concepts of transactions, introduce the various problems faced by concurrent transactions along with their corresponding solutions, and provide a detailed explanation and analysis of Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI), including its concept and implementation.

Basic Concepts

A transaction in a database is a way to group multiple read and write operations into a single logical unit. A transaction either commits successfully or aborts (or rolls back). This characteristic of transactions greatly simplifies the issues that application developers need to consider when interacting with a database (e.g., partial failures).

The safety guarantees provided by transactions are commonly described by the ACID properties:

- Atomicity

- Consistency

- Isolation

- Durability

We will focus on the implementation of Isolation, which describes the behavior of a database when handling concurrent transactions. In the case of concurrent transactions, the database faces problems such as dirty reads, dirty writes, and nonrepeatable reads. To address these issues, different transaction isolation levels provide corresponding guarantees.

- Dirty Read: A transaction reads modifications made by another concurrent, uncommitted transaction.

- Dirty Write: A transaction's modifications overwrite changes made by another concurrent, uncommitted transaction.

- Read Skew (Nonrepeatable Read): Reading the same value at different times within a transaction yields different results.

- Lost Update: When concurrent transactions modify the same record, the changes made by the earlier (committed) transaction might be lost, as the later transaction overwrites them.

- Write Skew: Two concurrent transactions read the same data and update different records based on that data, ultimately violating the expected consistency constraints.

- Phantom Read: A transaction’s writes change the result set of a range query executed by another transaction.

Dirty Write refers to a transaction overwriting modifications made by another uncommitted transaction.

Lost Update occurs when concurrent transactions read the same object and then update the same object based on stale data, causing updates to be lost.

Write Skew happens when concurrent transactions read the same data under specific conditions and then update different objects based on those reads. Although these updates do not conflict directly, they may violate business constraints.

Snapshot Isolation

To address nonrepeatable reads or read skew, we can use Snapshot Isolation (SI).

As the name suggests, snapshot isolation means that the visibility scope of a transaction is a consistent snapshot of the database taken at the start of the transaction. During the lifetime of the transaction, modifications made by other concurrent transactions are not visible.

Snapshot isolation is usually implemented in conjunction with MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control) because different transactions need to see the state of the database at different points in time, which requires maintaining multiple versions of the data.

In MySQL’s InnoDB storage engine, each transaction is assigned a monotonically increasing unique transaction ID (transaction id) based on its creation time. To implement MVCC, each data row in the database maintains multiple versions (managed through undo logs), and each version is tagged with the transaction id of the transaction that created it.

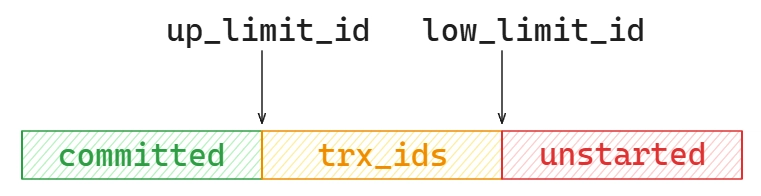

To determine which versions of the data are visible to the current transaction and which are not, InnoDB constructs a consistent view (read view) when the transaction is created. The consistent view contains four important fields:

- trx_ids: A list of IDs for all uncommitted transactions at the time the view was constructed.

- up_limit_id: The smallest transaction ID in trx_ids. All transaction IDs smaller than this value are considered committed.

- low_limit_id: The next transaction ID that has not yet been assigned at the time the Read View was created.

- creator_trx_id: The transaction ID of the transaction that created this consistent view.

We can visualize this consistent view as follows:

Transaction IDs greater than or equal to up_limit_id do not necessarily mean that those transactions have not committed. up_limit_id only guarantees that all transaction IDs smaller than it have committed, but it does not imply that all IDs greater than or equal to it are uncommitted.

With this view, we can determine the visibility of each data row version to the current transaction by comparing the row’s transaction id with the fields of the read view:

- If the transaction id falls in the green area (txn_id < up_limit_id), the data version was created by a committed transaction and is visible.

- If the transaction id falls in the red area (txn_id >= low_limit_id), the data version was created by a transaction that has not yet started and is not visible.

- If the transaction id falls in the orange area (up_limit_id <= txn_id < low_limit_id), there are two cases:

- If txn_id is in the trx_ids array, it means the transaction is uncommitted and the data version is not visible.

- If txn_id is not in the trx_ids array, it means the transaction has committed and the data version is visible.

Through the Read View and visibility rules, we ensure that a transaction always sees a consistent snapshot of the database during its execution, thus implementing the snapshot isolation level.

Serializable

Snapshot isolation cannot handle write skew and phantom read scenarios. To address these issues, we need Serializable isolation.

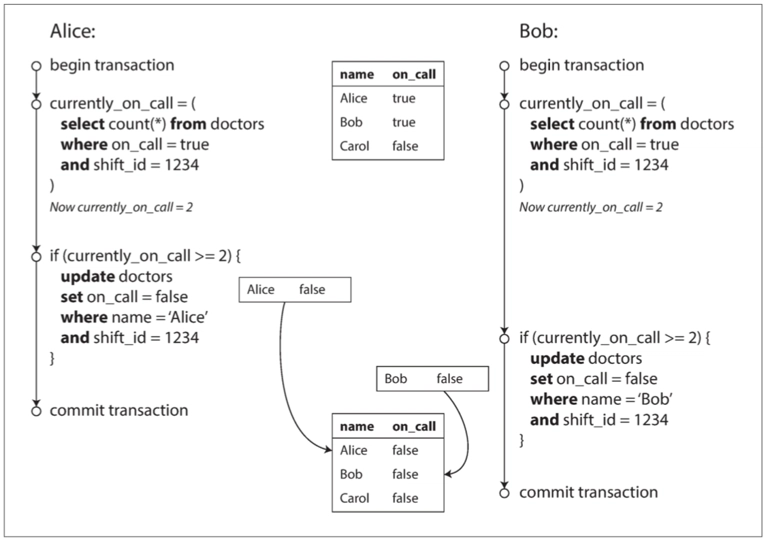

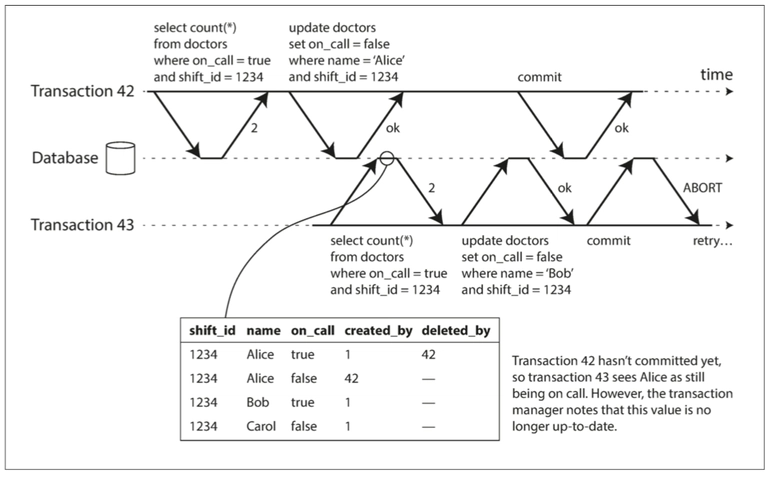

Let’s start with an example of write skew:

In this scenario, we need to ensure that at least one doctor remains on-call. Suppose Doctors Alice and Bob both submit leave requests (removing their on-call status) at the same time. Because their requests start concurrently, they both see the same consistent snapshot of the database. This leads them to believe there are still multiple doctors on-call, so they both remove themselves from on-call status and successfully commit their transactions. While this behavior is acceptable under snapshot isolation, it violates the rule that at least one doctor must remain on-call.

Under the serializable isolation level, this kind of situation can be avoided. Depending on the implementation, one of the concurrent transactions may be blocked or aborted.

Serializable isolation ensures that multiple transactions appear to execute in a serial order, even though they are actually executed concurrently. This prevents all possible race conditions. There are generally three approaches to achieve serializability:

Truly serial execution: Transactions are executed one at a time in a single thread, limiting transaction throughput to the speed of a single core. Alternatively, if the dataset supports partitioning without cross-partition coordination, each partition can utilize its own CPU core independently.

Two-Phase Locking (2PL): This approach uses locks on data objects. Locks are divided into shared locks (Share mode) for reading and exclusive locks (Exclusive mode) for writing or modifying data. Shared and exclusive locks conflict with each other, and exclusive locks conflict with other exclusive locks. However, 2PL can lead to deadlocks and lock waits, making its performance much worse than weaker isolation levels.

Mechanisms like Next-Key Lock and Record Lock also have shared and exclusive modes.

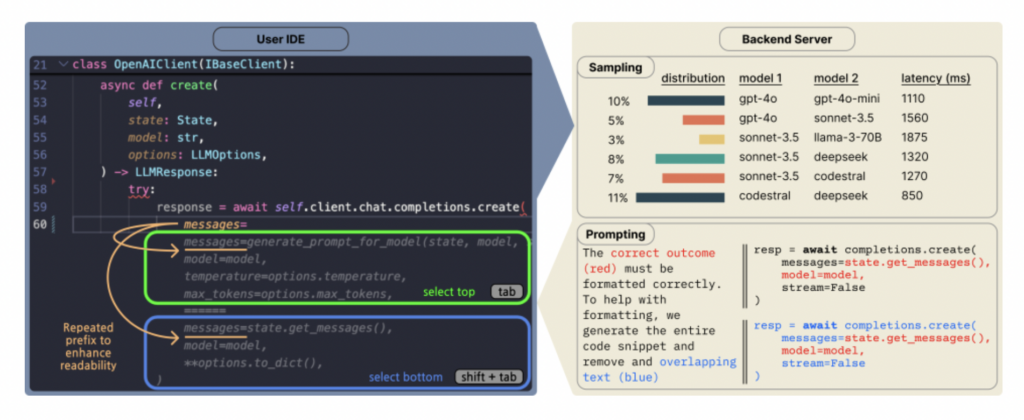

- Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC): While 2PL is a pessimistic concurrency control mechanism (using locks and only releasing them once safety is ensured), Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) is based on optimistic concurrency control. Even though potential conflicts may occur during transaction execution, these conflicts are only checked at commit time to verify whether isolation guarantees have been violated. When transaction contention is low, optimistic concurrency control performs well.

The goal of Serializable isolation is to ensure that the overall effect of transaction execution is equivalent to some serial order. However, it does not guarantee that every read sees the most recent value (i.e., the latest write).

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) provides full serializability with only minimal overhead compared to standard snapshot isolation. SSI can be viewed as adding a conflict detection algorithm on top of snapshot isolation to detect serialization conflicts between writes. All reads still operate on a consistent snapshot taken at the start of the transaction.

The root cause of write skew under snapshot isolation is that transactions make decisions based on outdated consistent snapshots. Since the data read from the snapshot might have been modified by another committed concurrent transaction, the transaction could be working with stale data.

In other words, we need an algorithm that can detect whether the data read by the current transaction has been modified by a concurrent transaction that committed before us.

The concurrent transactions referred to here are the two types of invisible transactions discussed in the visibility rules of snapshot isolation. In both cases, these transactions' modifications are not visible to our current transaction's consistent snapshot:

- Transactions that have not yet started;

- Transactions that have started but not yet committed.

Let’s revisit the previous write skew example and consider two possible scenarios:

- Write-then-Read

In this scenario, Transactions 43 and 42 operate on the same consistent snapshot. Transaction 43 reads data, while Transaction 42 modifies that data (although the modification is not yet committed). If Transaction 42 commits before Transaction 43, it means that Transaction 43 has read stale data. Therefore, when Transaction 43 attempts to commit, it must be aborted.

Why wait until commit time to abort?

- Transaction 42 might abort first, invalidating its modifications.

- Transaction 42 might commit later, which wouldn't conflict.

- Transaction 43 might be a read-only transaction, meaning it wouldn’t cause write skew.

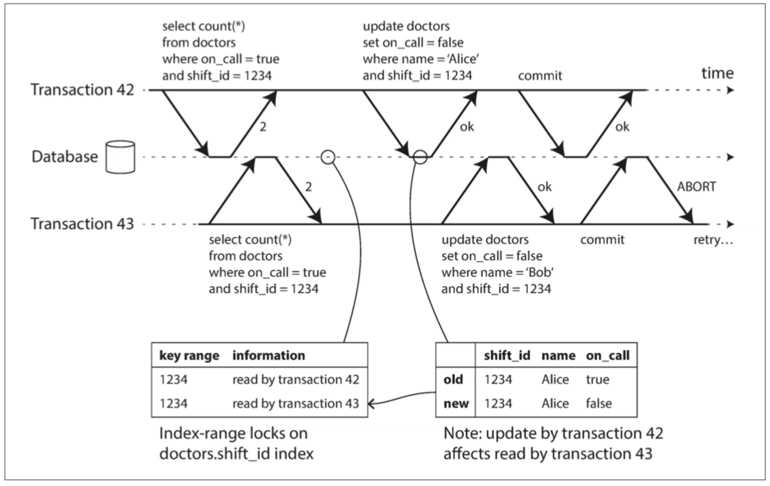

- Read-then-Write

In this scenario, Transactions 43 and 42 also operate on the same consistent snapshot. Transaction 43 performs reads before Transaction 42 modifies the data. However, if Transaction 42 commits before Transaction 43, the data read by Transaction 43 becomes stale. As a result, when Transaction 43 tries to commit, it is aborted.

To implement this conflict detection algorithm, we need to either:

- Notify concurrent transactions that read data modified by the current transaction at commit time; or

- Record the data modified by concurrent transactions and check at commit time whether the current transaction has read any of this data.

This ensures that no transaction can commit based on stale reads, thus achieving serializability.

Implementation

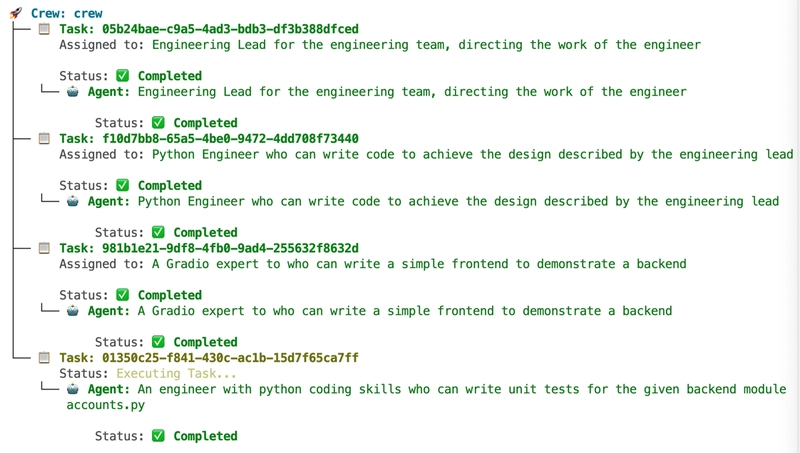

In this section, we will implement Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) ourselves to provide transaction support for the database. However, the database we are working with is a key-value store (NoSQL) that uses an LSM-Tree storage engine, rather than the more common relational database (RDBMS).

That said, the core idea behind implementing SSI is shared between both systems. Providing SSI support for a key-value database is relatively simpler.

As mentioned in the concept introduction section, SSI is built on top of the snapshot isolation (SI) transaction isolation level. This means we first need to implement snapshot isolation, and then, on top of that, implement an algorithm to detect serialization conflicts between concurrent transactions.

In this implementation section, we won’t dive too deeply into specific code details. Instead, we will focus on how the various components work together. For the complete code, please refer to the implementation at https://github.com/B1NARY-GR0UP/originium.

Transaction Start and Commit Timestamps

The first problem we need to solve is: How do we determine the start and commit timestamps of a transaction?

- The start timestamp is used to determine the range of the consistent snapshot that the transaction can see.

- The commit timestamp is used in SSI to determine the commit order between concurrent transactions.

By comparing the commit timestamp of other transactions with the start timestamp of the current transaction, we can determine whether there might be a serialization conflict between the two transactions. Additionally, the commit timestamp serves as a version identifier for the data we store. When paired with the transaction’s start timestamp, this enables snapshot isolation.

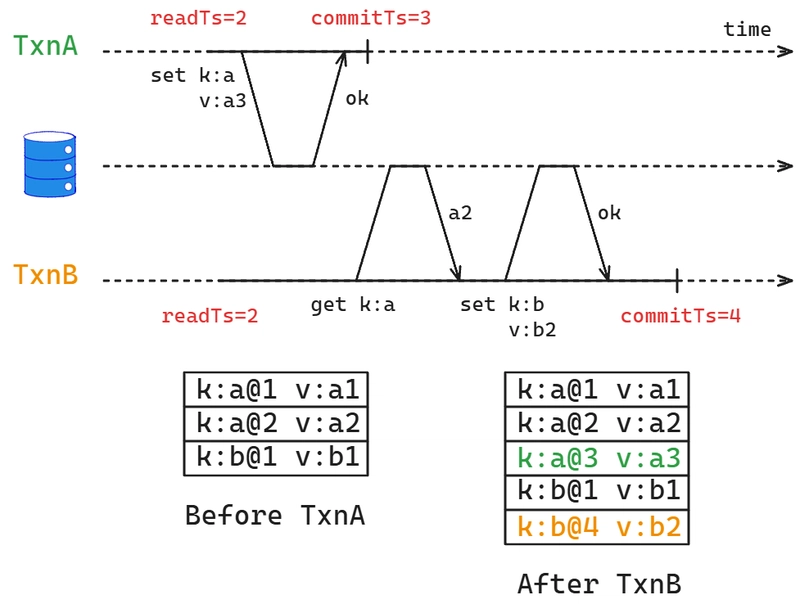

For simplicity, we use readTs to represent a transaction’s start timestamp and commitTs to represent its commit timestamp. The rules for managing readTs and commitTs are as follows:

- Both

readTsandcommitTsare integer timestamps starting from 0. - Each transaction is assigned a monotonically increasing

commitTsat commit time. - Each transaction is assigned a

readTsat the start, which equals the current global maximumcommitTs. Before starting, the transaction waits for all transactions withcommitTsless than or equal to this value to either commit or abort. - A transaction can only see data versions whose commit timestamps are less than or equal to its

readTs.

Let’s walk through a simple example to illustrate:

Before TxnA and TxnB start, our database contains three key-value pairs. The value after the @ symbol represents the version of the key. For example, k:a@2 v:a2 indicates that the key a has the value a2 at version 2. When TxnA and TxnB begin, there are no active transactions in the database. Both transactions receive a readTs of 2 (which is the current maximum commitTs in the database). TxnA commits a new value for key a and gets a commitTs of 3, which is monotonically increasing. TxnB, during its transaction, reads the value of key a. Since its readTs is 2, it does not see TxnA’s newly committed version 3 of key a. Instead, it reads the previous version of key a with value a2. TxnB also sets a new value for key b and commits, receiving a commitTs of 4, which again increases monotonically.

Conflict Detection

The second issue we need to address is: How do we detect serialization conflicts caused by concurrent transactions?

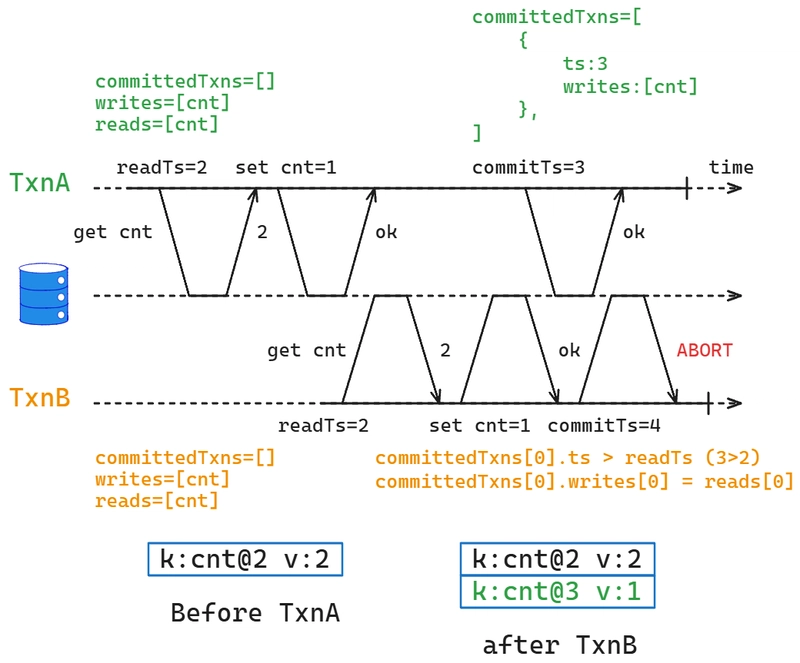

In our earlier discussion, we considered two scenarios that can lead to write skew and concluded that the key to detection is determining whether the data read by the current transaction has been modified by a concurrent transaction that committed before the current one. The detection logic we use here is simple and straightforward: we only need to record the keys read by the current transaction and the keys modified by concurrently committed transactions, then check if there’s any overlap between them.

Let’s first walk through the general execution flow before diving into the details of conflict detection:

- Record the keys read and written by a transaction.

- Perform conflict detection at commit time; if a conflict is found, abort the transaction immediately.

- If no conflict is found, record the keys written by the transaction along with its assigned

commitTsin a globally maintained array.

This globally maintained array is the core mechanism we use to implement conflict detection. It keeps track of the keys modified by all transactions that could potentially conflict with the current transaction. Here’s how our conflict detection process works:

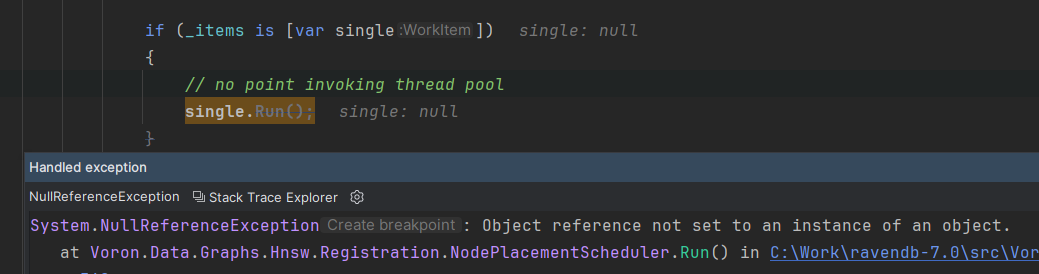

func (o *oracle) hasConflict(txn *Txn) bool {

if len(txn.readsFp) == 0 {

return false

}

for _, ct := range o.committedTxns {

if ct.ts <= txn.readTs {

continue

}

for _, fp := range txn.readsFp {

// a conflict occurred when curr txn read a key that be modified by a committed txn

if _, ok := ct.writesFp[fp]; ok {

return true

}

}

}

return false

}

The array, called committedTxns, holds information about all committed transactions. At commit time, we select the transactions from this array that committed after the current transaction’s readTs (> txn.readTs), and check whether any of their written keys overlap with the keys read by the current transaction. If there’s an overlap, it means the data read by the current transaction’s consistent snapshot has already been modified by another committed concurrent transaction, and we return true to indicate a conflict.

One important detail to note is that we cannot allow the committedTxns array to grow indefinitely. We need to periodically clean up the committed transactions that are no longer needed—specifically, those whose commitTs is earlier than the earliest active transaction in the system. These transactions can no longer conflict with any active transactions.

Let’s revisit the write-then-read example we discussed earlier and walk through the process again to see how our implementation handles write skew:

As shown in the diagram, the committedTxns array is initially empty because there are no transactions with commitTs > 1 in the system. TxnA modifies a key and commits before TxnB. At this point, TxnA’s modified keys are recorded in committedTxns. When TxnB tries to commit, TxnA’s commitTs is greater than TxnB’s readTs, and TxnB has read a key that TxnA modified. Since there is an overlap, a conflict is detected, and TxnB is aborted.

Discarding Old Data Versions

Handling old data versions is the final issue we need to consider. If we do not periodically clean up old data versions, the database will accumulate a large number of obsolete versions, wasting storage space and degrading overall performance.

Different databases have their own strategies and implementations for when and how frequently to clean up old data versions. Here, we mainly focus on defining the scope of data version cleanup—specifically, which versions can be safely discarded.

Our conclusion is: for each key-value pair, we retain all versions with a version number greater than or equal to the readTs of the earliest active transaction in the system. For versions with a version number less than the readTs of the earliest active transaction, we only keep the latest version.

This cleanup rule is similar to InnoDB’s mechanism, where InnoDB removes undo logs for all data versions whose transaction IDs are less than the ID of the earliest active transaction. Since the latest version resides in the main table, it is not removed.

Once we understand this cleanup rule, the next question is: how do we determine the readTs of the earliest active transaction in the system, and how is this value maintained? In InnoDB, each transaction maintains a list of active transaction IDs at the time it is created. This list is generated from a global list of active transactions, which allows InnoDB to determine the ID of the earliest active transaction for cleanup and other purposes.

In our implementation, we can adopt a similar approach by using a structure that globally tracks the active state of transactions in the system. We call this structure WaterMark.

The main methods of WaterMark are as follows:

-

Begin: Starts tracking a timestamp. -

Done: Stops tracking a timestamp. -

DoneUntil: Returns a value, indicating that all timestamps less than or equal to this value have been completed.

Using these three core methods, we can track the active transactions in the system. When a transaction starts, we track its readTs, and when it commits or aborts, we stop tracking that readTs. By calling DoneUntil, we can obtain the safe range for cleaning up old data versions.

Conclusion

Starting from the concept of transactions, we explored the various issues that arise with concurrent transactions and completed an analysis of how to implement Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI). We hope this helps deepen your understanding of these concepts.

That wraps up the content of this article. If there are any mistakes or issues, feel free to reach out via private message or leave a comment below.

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

_Muhammad_R._Fakhrurrozi_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_NicoElNino_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![macOS 15.5 beta 4 now available for download [U]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/04/macOS-Sequoia-15.5-b4.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![AirPods Pro 2 With USB-C Back On Sale for Just $169! [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96315/96315/96315-640.jpg)

![Apple Releases iOS 18.5 Beta 4 and iPadOS 18.5 Beta 4 [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97145/97145/97145-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds watchOS 11.5 Beta 4 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97147/97147/97147-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds visionOS 2.5 Beta 4 to Developers [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97150/97150/97150-640.jpg)

![Apple Seeds Fourth Beta of iOS 18.5 to Developers [Update: Public Beta Available]](https://images.macrumors.com/t/uSxxRefnKz3z3MK1y_CnFxSg8Ak=/2500x/article-new/2025/04/iOS-18.5-Feature-Real-Mock.jpg)

![Apple Seeds Fourth Beta of macOS Sequoia 15.5 [Update: Public Beta Available]](https://images.macrumors.com/t/ne62qbjm_V5f4GG9UND3WyOAxE8=/2500x/article-new/2024/08/macOS-Sequoia-Night-Feature.jpg)