You’re Not the First. You Won’t Be the Last. But We Survive

This is a submission for the WeCoded Challenge: Echoes of Experience I didn’t grow up dreaming of being in tech - it just happened, one decision at a time. I was born in a provincial city in Belarus in a family of an engineer and an economist. We lived in a marginal neighborhood - not in complete poverty, but definitely on the rougher side of town. For example, one floor below us there was a semi-legendary “blat khata” where local alcoholics used to hang out, drink and argue loudly well into the night. Still, somehow we managed. Thanks to my enrollment in music school I eventually ended up in a slightly better city school, one of those quiet, accidental wins you only come to appreciate much later. When your dad is an engineer, it leaves a mark. At the age of three my mom found me with a screwdriver in hand, halfway through disassembling a nightlight while it was still plugged in. I actually managed to get it half open. My dad sometimes took me with him to his job at the factory, where I’d hang out with the guys from his department as they taught me how to play color Tetris on their computers - which, back in 1990, was absolute cutting-edge. At some point, he brought home an Elektronika MK-90 - a Soviet microcomputer that was seriously advanced for the time. Basically, the iPad of its era, if your iPad had a monochrome screen. When I was seven, I found its programming manual and copied my first program straight from the book. I had no real idea what I was doing, but it ran and that was enough. In 2002, our family got its first proper computer - a second-hand Pentium II with a noisy matrix printer - and I remember playing Solitaire and Freddi Fish for the first time and thinking, well, that’s something. Looking back now I realize that neither in my family nor in my school did anyone ever tell me that women couldn’t do certain things - if anything, it was quite the opposite: my math class was 90 percent girls, and when I moved to the informatics group, it turned out to be 100 percent girls. I think I was unusually lucky in that sense. My parents were strict and kept my social life under tight control, monitoring everything I did and maybe because of that I simply didn’t absorb the usual messages about what women supposedly can’t or shouldn’t do. Not all the girls I knew were that lucky, some were raised to believe that their first and most important job in life was to get married and have children. Despite being in an informatics-focused class and having consistently high grades in math and physics it had never occurred to me that this could actually become my profession - which might have been for the best. I had other plans. I wanted to be a doctor, a surgeon, actually, if you can imagine the level of ambition. I still remember a lot of biology and chemistry, and to this day I have an irrational love for medical equipment - nothing quite excites me like a CT machine. My mom, however, had very different plans for me. When I said I wanted to go to medical school, she answered, “only over my dead body,” and that pretty much settled it. So I applied to the first artificial intelligence program at the university in my city - it sounded interesting and I didn’t have a better plan. Our group was officially called "Artificial Intelligence 1" which, as it turned out, became an endless source of jokes for our professors for years to come. After the first year summer came and I had nothing to do, so I started learning C++ from a book. Exams were only twice a year, nothing felt particularly hard. Looking back now, I realize the curriculum itself wasn’t exactly cutting-edge - it was heavily outdated and followed the best traditions of Soviet education, which meant that about 40 percent of the subjects weren’t technical at all and had little to do with programming or artificial intelligence. The professors were also, let’s say, from another era. For example, the course on "radiation safety" was taught by a woman who, back in the year 2000, became convinced the world was ending and disappeared underground for nine months with a doomsday cult. Honestly, I hope she made it through COVID years - she probably had the best prep plan out of all of us. Still, at the time, nothing seemed especially strange or difficult. And in a way I think going through all that low-grade chaos did help - because once you get used to handling that kind of madness, you can pretty much handle anything. Though I did notice one thing - out of 29 people in my university group, only five including me were girls and that did feel a little strange. I still had no idea that women weren’t “supposed” to be doing this kind of thing, but something about those numbers stuck with me. In my second year, my C++ professor told me I had “female logic.” God, I hope he never reads this, because I actually liked him. I honestly asked what kind of logic he thought that was. I still hadn’t failed a single exam, passed everything on the first try and my g

This is a submission for the WeCoded Challenge: Echoes of Experience

I didn’t grow up dreaming of being in tech - it just happened, one decision at a time.

I was born in a provincial city in Belarus in a family of an engineer and an economist. We lived in a marginal neighborhood - not in complete poverty, but definitely on the rougher side of town. For example, one floor below us there was a semi-legendary “blat khata” where local alcoholics used to hang out, drink and argue loudly well into the night. Still, somehow we managed. Thanks to my enrollment in music school I eventually ended up in a slightly better city school, one of those quiet, accidental wins you only come to appreciate much later.

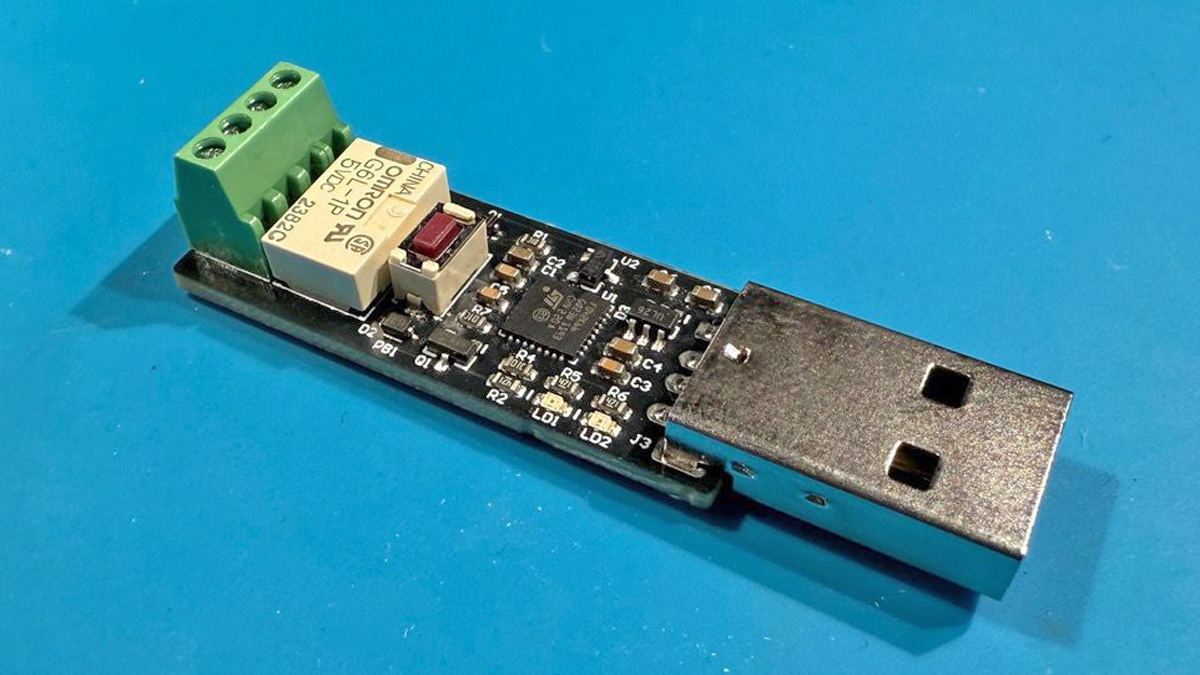

When your dad is an engineer, it leaves a mark. At the age of three my mom found me with a screwdriver in hand, halfway through disassembling a nightlight while it was still plugged in. I actually managed to get it half open. My dad sometimes took me with him to his job at the factory, where I’d hang out with the guys from his department as they taught me how to play color Tetris on their computers - which, back in 1990, was absolute cutting-edge.

At some point, he brought home an Elektronika MK-90 - a Soviet microcomputer that was seriously advanced for the time. Basically, the iPad of its era, if your iPad had a monochrome screen. When I was seven, I found its programming manual and copied my first program straight from the book. I had no real idea what I was doing, but it ran and that was enough.

In 2002, our family got its first proper computer - a second-hand Pentium II with a noisy matrix printer - and I remember playing Solitaire and Freddi Fish for the first time and thinking, well, that’s something.

Looking back now I realize that neither in my family nor in my school did anyone ever tell me that women couldn’t do certain things - if anything, it was quite the opposite: my math class was 90 percent girls, and when I moved to the informatics group, it turned out to be 100 percent girls. I think I was unusually lucky in that sense. My parents were strict and kept my social life under tight control, monitoring everything I did and maybe because of that I simply didn’t absorb the usual messages about what women supposedly can’t or shouldn’t do. Not all the girls I knew were that lucky, some were raised to believe that their first and most important job in life was to get married and have children.

Despite being in an informatics-focused class and having consistently high grades in math and physics it had never occurred to me that this could actually become my profession - which might have been for the best. I had other plans. I wanted to be a doctor, a surgeon, actually, if you can imagine the level of ambition. I still remember a lot of biology and chemistry, and to this day I have an irrational love for medical equipment - nothing quite excites me like a CT machine.

My mom, however, had very different plans for me. When I said I wanted to go to medical school, she answered, “only over my dead body,” and that pretty much settled it. So I applied to the first artificial intelligence program at the university in my city - it sounded interesting and I didn’t have a better plan. Our group was officially called "Artificial Intelligence 1" which, as it turned out, became an endless source of jokes for our professors for years to come.

After the first year summer came and I had nothing to do, so I started learning C++ from a book. Exams were only twice a year, nothing felt particularly hard. Looking back now, I realize the curriculum itself wasn’t exactly cutting-edge - it was heavily outdated and followed the best traditions of Soviet education, which meant that about 40 percent of the subjects weren’t technical at all and had little to do with programming or artificial intelligence. The professors were also, let’s say, from another era. For example, the course on "radiation safety" was taught by a woman who, back in the year 2000, became convinced the world was ending and disappeared underground for nine months with a doomsday cult. Honestly, I hope she made it through COVID years - she probably had the best prep plan out of all of us.

Still, at the time, nothing seemed especially strange or difficult. And in a way I think going through all that low-grade chaos did help - because once you get used to handling that kind of madness, you can pretty much handle anything.

Though I did notice one thing - out of 29 people in my university group, only five including me were girls and that did feel a little strange. I still had no idea that women weren’t “supposed” to be doing this kind of thing, but something about those numbers stuck with me.

In my second year, my C++ professor told me I had “female logic.” God, I hope he never reads this, because I actually liked him. I honestly asked what kind of logic he thought that was. I still hadn’t failed a single exam, passed everything on the first try and my grades were just fine. Later our database professor announced that women only go to tech universities to find husbands. Frankly, he should’ve focused more on modern tech - maybe then our final course project wouldn’t have been on FoxPro.

In my fourth year some classmates decided to join extra courses run by a big tech company. Nobody invited me. They were happy to borrow my lab assignments, but when it came to real opportunities, I didn’t make the list. I got annoyed - maybe even quietly offended - and decided to find a job, mostly just to prove a point. It didn’t even cross my mind that students usually don’t get hired. I had no idea how job searches were supposed to work. I saw the first listing online and sent an email.

To my surprise, they called. They were open to students and invited me to an interview. I think it went fine - they asked some C++ questions, I answered. Then they said, if you bring two more students, we’ll take you too. I brought two. They hired me. Only years later did I find out that there were people in that company who were strongly against having a woman around. At the time, I was the only one.

My first salary was one hundred dollars and of course, I went and bought shoes - what else are you supposed to do with your first paycheck. I was juggling classes and work, still unsure what kind of specialist I wanted to be or what exactly I wanted to do, mostly figuring things out as I went. I was lucky - my mentor at work turned out to be incredible. He actually taught me how to code, not the abstract university stuff, but real working code that made sense and did things, and even more importantly, how to think about problems like a developer.

I graduated with honors, got my "red" diploma, a raise and was assigned to my first official project - a game for one of the early iPods with a screen, something I worked on as part of a team. It was also the first time I ever touched an Apple product and I didn’t even realize I was supposed to be impressed - what do you expect from someone who grew up in the post-Soviet space? Nobody told me Apple was cool. But even then I already sensed that plain coding - sitting and writing logic in a vacuum - wasn’t really my thing. Something was missing.

When the game project wrapped up, they moved me to work on installation scripts. That shift turned out to be unexpectedly great - suddenly I was talking not just to developers, but to QA, product managers, release managers - to all our foreign colleagues. I started seeing how everything fit together. I realized I actually liked understanding processes, not just writing code. That part felt real.

I worked days and nights, weekends too - the installer is always the last stop before release and the last stop always gets the Friday night surprises. Still, I genuinely liked the work, I liked the team, I liked being part of this company. I didn’t pay much attention to the toxic air of classic Eastern European tech culture - at the time, I thought it was normal. That’s just how men talk. That’s just how things are.

I went through that classic phase where I didn’t like anything “feminine.” I thought dresses were stupid and if you wore makeup, you probably weren’t very smart. I didn’t want to be seen as weak or emotional or soft. I wanted to belong. You don’t take things personally. You stay strong. You’re not some delicate girl. And honestly, it was hard to put any gender stereotype on me - I never understood why the girls in the office were the ones expected to slice vegetables for the holiday party. Just hire a caterer. Why was that my problem? Some of other women in the company seemed fine with it, but I just didn’t get it.

And it still all felt bearable - until I became a team lead and got a big raise. By then there were finally some other women in the company, mostly in QA and design, but still none in engineering except me. And suddenly the vibe shifted. One evening at a company party, a colleague asked me - completely seriously and aggressively - what exactly I’d done to earn that kind of raise. How he even knew about it, I’m not sure - raises were supposed to be confidential.

That was the moment I started to truly understand how things worked - and where I stood in all of it. Then I went on a work trip abroad and for the first time I saw that it could all be different.

I never seriously considered moving abroad. Some of my colleagues were making real plans, studying languages, preparing, but I always thought that kind of life was meant for someone else - for Real Proper Programmers, with capital letters. Not for someone like me. Where was I and where were they.

By 2015 I had already gone through enough: the death of my father, a few painful betrayals and a growing feeling that I had outgrown the life I was living.

Long story short, in 2015 I moved to another country to live with my future husband. It was a cultural shock in every possible sense. I kept working remotely for a while and only in 2017 I finally got a proper work visa. In the meantime, I enrolled in a local university to study economics, started learning a new language from scratch and also realized that my English was far from good enough. I found a tutor - a woman, native speaker, a writer from New York - and started lessons. I think at that point my second name officially became “doing too much at once.”

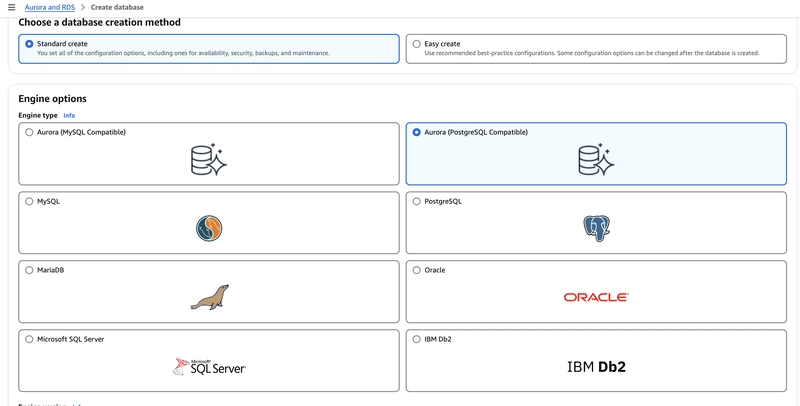

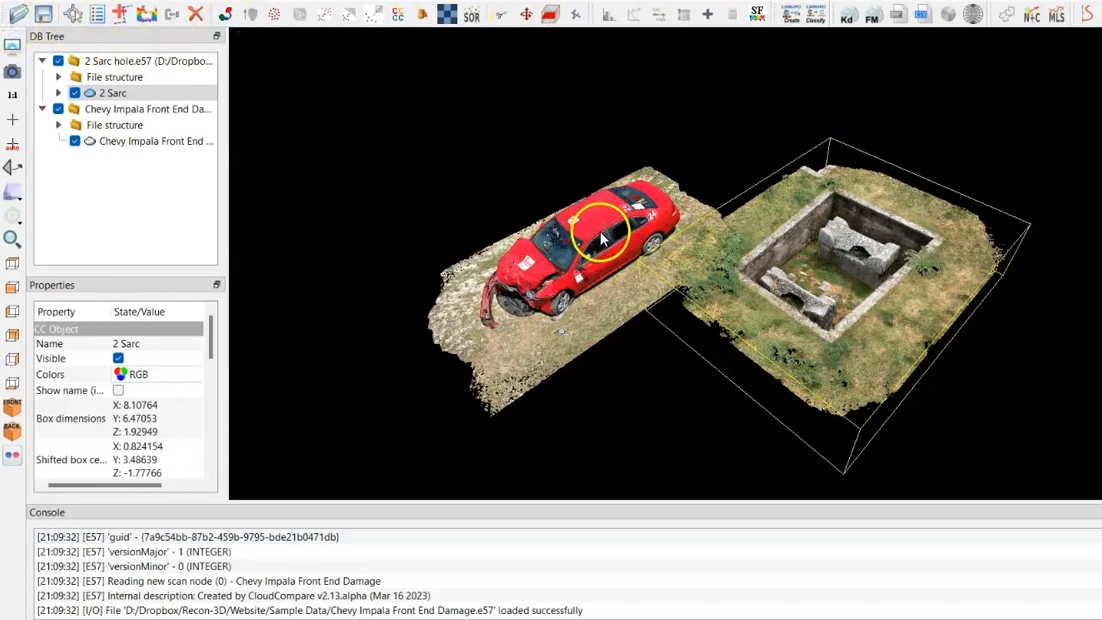

That same year I got lucky again. My former company agreed to hire me at their office as a BI engineer. I knew close to nothing about BI, I could write a SQL query maybe. Within the next year we rewrote the entire legacy BI stack from PHP (did I know PHP? not really) to Python and Hadoop. They made me a team lead again. Then an R&D manager. I cried in bathroom stalls more than I’d like to admit. And I still didn’t see any other women in engineering around me.

In 2018 the company suddenly shut down. Just like that, I found myself unemployed and it was a complete shock. I started looking for a new job and for the next six months I couldn’t find anything. Some companies rejected me immediately because lack of the local language (which isn’t an issue anymore, but it definitely was back then), others because I couldn’t seem to explain who I actually was.

Was I a BI person? That surprisingly didn’t pay much. A developer? I wasn’t really enjoying it. A team lead? Apparently not experienced enough for the local market. An R&D manager? Nobody believed it. So I applied to everything, got ignored by almost everyone and in the process collected an impressive amount of tech industry weirdness.

There was the interview where the guy was clearly high, talked about himself for an hour and then messaged me the next day to say I was too old for their young startup culture - I was 33. The one where the CTO stood up and left five minutes after I walked in - to be fair, I had just finished explaining that I thought building a tool to recognize cat speech would be a fun idea. I don’t know, maybe he was a dog person... The endless take-home tasks that took two or three full days and led to absolutely nothing. The one where someone asked how I deal with stress and didn’t find “crying in the bathroom” nearly as funny as I did. The endless whiteboard sessions. One proud VP R&D told me that asking Fibonacci was his original idea - which, I'm sure, would’ve come as a surprise to Fibonacci himself. My personal favorite was the phone interview where the guy asked me “In what year were non-relational databases invented?” and then hung up on me after my confused pause - and honestly, I still don’t know when exactly. There was also the company that rejected me because, as I later learned from an insider, the VP R&D got the feeling that I didn’t like him. Yes, the company had two VPs of R&D - which, for a tiny startup, already raises a few questions.

I completely burned out from the job search. I still get flashbacks when I see certain company names. My husband started saying I have a talent for attracting unhinged people.

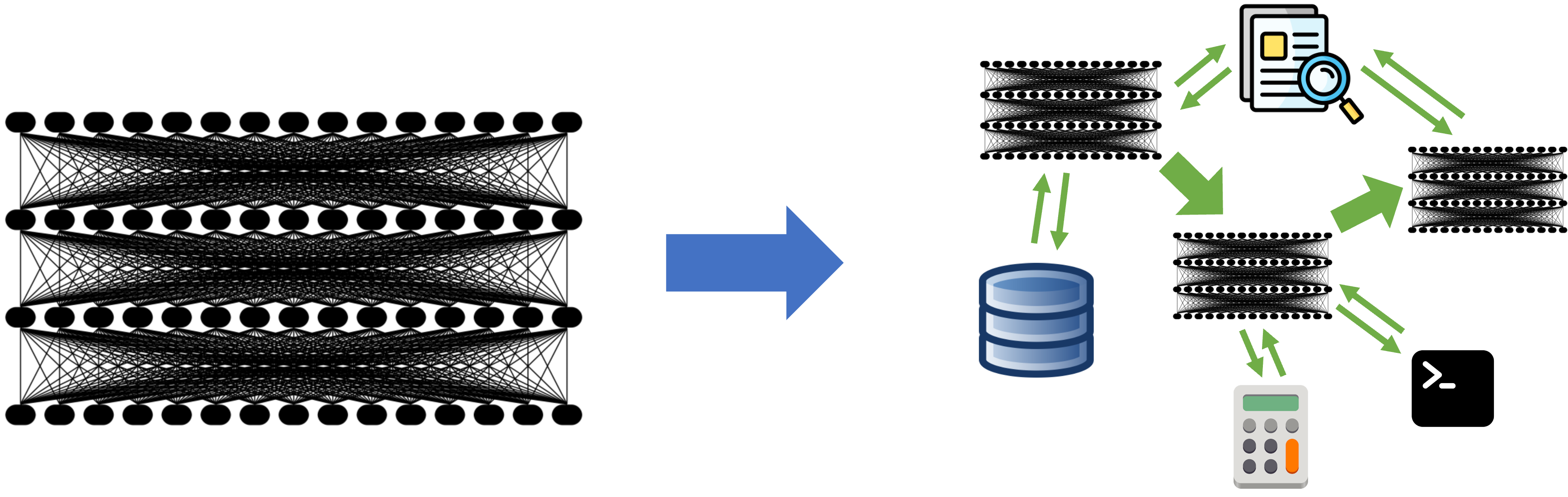

At some point I interviewed with the CEO of a startup that had just been acquired by a well-known huge American company - the kind that regularly puts out ads about diversity and women. At the end of the interview he asked me if I wanted kids which is, of course, illegal to ask - but it was just the two of us in the room, so what could I do. That was the moment it finally hit me: something about the way I was approaching all this was deeply wrong. I started writing down red flags, taking notes after interviews, setting boundaries. If something felt off at the first stage, I didn’t continue. One day, when AI replaces us all and we finally get kicked out of the industry, I’ll write a post about my personal red flags - and it’s going to be a masterpiece. But for now I’m not writing it, because if I publish that thing, no one will ever hire me again. Back then I took a step back, did some thinking and realized that what I really liked was data engineering - not analytics, not research, but building pipelines, moving data around, making things work. So I focused, found a job, and three months later, a better one.

That’s when things finally started to make sense. I was doing what I actually liked - proper data engineering. I used to describe my job as “moving data from one database to another,” but in reality it was never that simple or that boring. I rebuilt the entire BI stack again - same story, different company - but this time with better tools, better planning and a better sense of what I was doing. I finally saw women working in engineering. I learned how to speak up, how to interrupt, how to hold space in a meeting. That’s just how it works here - if you don’t speak over someone, you might as well not exist. It’s funny now, but for a Belarusian girl raised to be quiet and polite, learning to raise my voice felt like trying to teach an elephant ballet.

Then 2020 came, and with it - COVID. First lockdown, second, third. At first it was even a little fun. But by the time I learned how to grow flowers on the balcony and bake focaccia, the novelty wore off completely. I burned out again, only this time it wasn’t from job hunting or bad managers - it was from the work itself. I couldn’t look at code. I couldn’t open a terminal. So I quit, walked away from a stable job at a solid company with a good salary. No, I don’t know what’s wrong with me either.

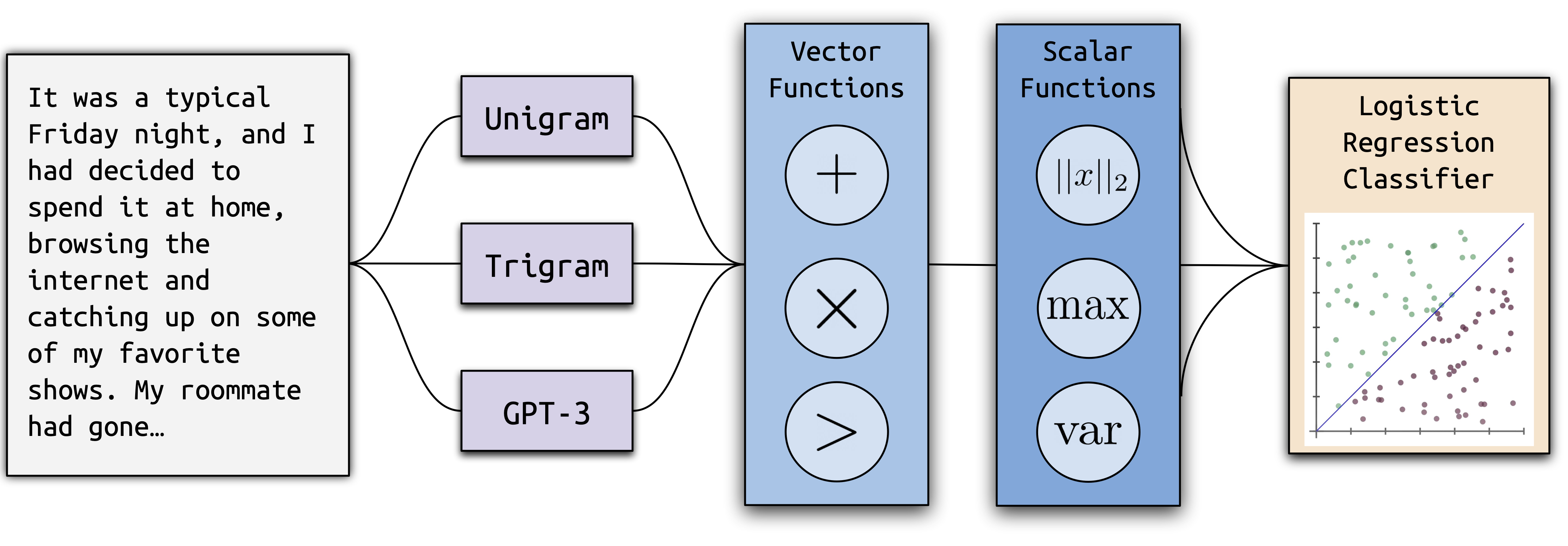

I spent two months sitting on the couch playing World of Warcraft and dreading the idea of going back to tech. I tried a machine learning course. Then another one. They were interesting in theory, but nothing clicked. I floated. Drifted. Made a few questionable decisions.

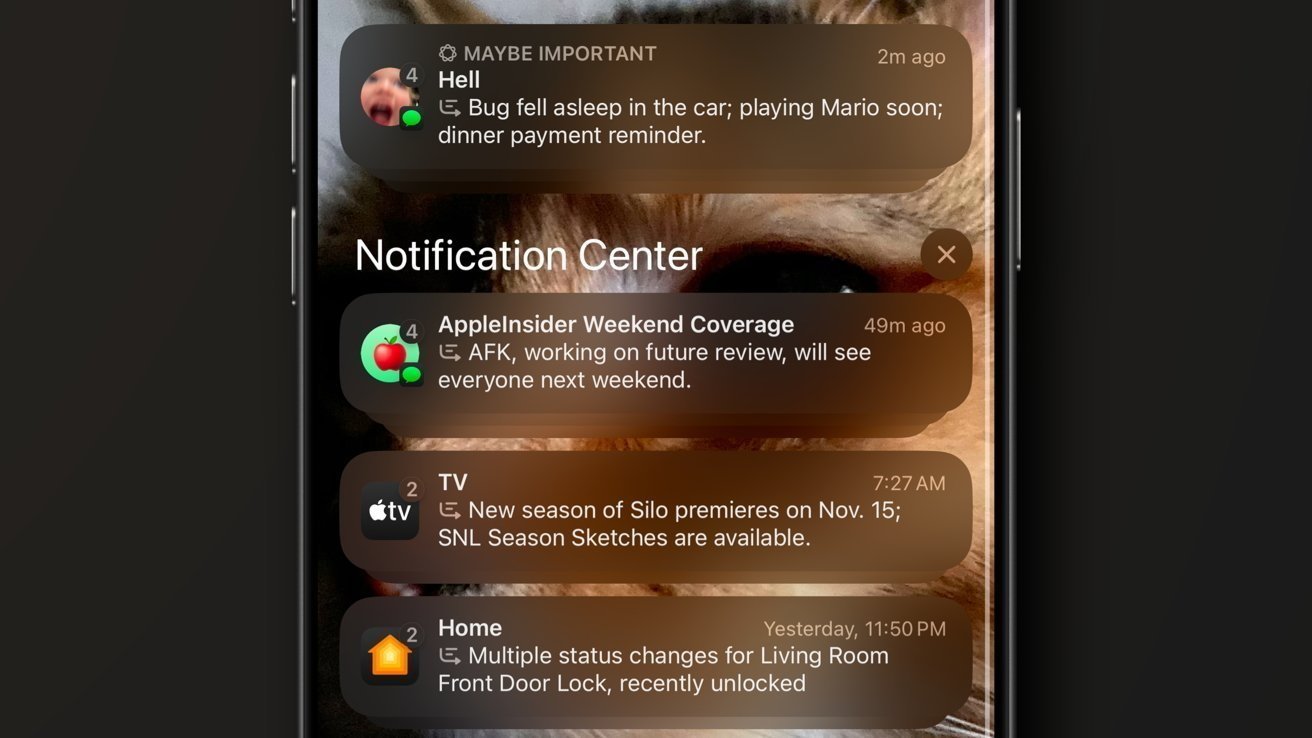

And then, in 2021, I wrote my first blog post on Medium. It was based on a real use case from my previous job - nothing groundbreaking, but honest, practical and very much mine. Somehow, it started showing up in newsletters, the stats kept climbing and I kept refreshing the page in disbelief. A month later I got a job offer. Not because of the blog post - blogging has brought me nothing but likes so far. I just saw a job opening, applied and got hired without all the usual weird nonsense - shoutout to the hiring manager who actually saw something in me and chose not to make it weird. Yes, back in tech. Again.

When I say I wrote my first blog post, it sounds way too casual - like I just sat down one evening and typed it out. In reality, I spent months suffering over it. Writing something for the first time, putting your voice out there, trying to explain even the simplest thing clearly - it was ridiculously hard. I rewrote it a hundred times, doubted every sentence, questioned whether I had anything worth saying at all. Turns out hitting “publish” is a whole emotional journey on its own.

You might think that was the moment I became a blogger. Not exactly. It took me another year and a half to write a second post - and even that one was for the company I worked at. Then I remembered one of my old POCs and figured, why let it rot - turned it into a third post. Somewhere along the way, blogging started pulling me in. I made a Notion page to track ideas and now it has around seventy. If only I had more time. Or discipline. Or both.

Since then I’ve been learning Go, taking deep learning courses, joining data camps, participating in Dev.to challenges - and somehow I keep staying in tech, no matter how many times I try to run away from it. These days I have new problems. Something in the “midlife crisis but make it career” category. I keep asking myself who I really am and what I actually want.

But while I was writing this story, I realized something important. If I’ve stayed in this field since 2008 - through burnout, relocation, layoffs, bad interviews, gender nonsense, imposter syndrome, bad managers and even worse codebases - if I’m still here, still working for money, still curious about new tools and occasionally opening Jupyter notebooks just for fun, then maybe I’m going to be okay. Maybe I’ve already proven something to myself.

I didn’t grow up dreaming of being in tech. I didn’t have a plan. I just made one decision after another and some of them worked out. This isn’t a success story. It’s just one story. One path. One version of how it can go. And if you’re somewhere in the middle of yours and it feels like a mess - that’s okay.

You’re not the first. You won’t be the last.

Somehow we keep going. And sometimes it even makes sense.

![[The AI Show Episode 142]: ChatGPT’s New Image Generator, Studio Ghibli Craze and Backlash, Gemini 2.5, OpenAI Academy, 4o Updates, Vibe Marketing & xAI Acquires X](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20142%20cover.png)

![[FREE EBOOKS] The Kubernetes Bible, The Ultimate Linux Shell Scripting Guide & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![From drop-out to software architect with Jason Lengstorf [Podcast #167]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1743796461357/f3d19cd7-e6f5-4d7c-8bfc-eb974bc8da68.png?#)

.png?#)

.jpg?#)

_Christophe_Coat_Alamy.jpg?#)

![Rapidus in Talks With Apple as It Accelerates Toward 2nm Chip Production [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96937/96937/96937-640.jpg)