Where to Start in Web Development: React, Angular, Svelte, or Somewhere Else?

Dear reader, if this is your n-th article in search of an answer to the question imposed in its title—and you don’t want to waste your time—the answer is: Somewhere Else. Why? The key phrase here is "where to start". If you’re just discovering web development field and want to begin somewhere, starting with any of these frameworks (React, Svelte, Vue and Angular are frameworks)—will only confuse you, because they’re definitely not the tools to start with web development. In this article, I will uncover what is behind this Somewhere Else. Even though, of course, HTML, CSS, and JavaScript (further - JS) are the fundamentals of web development, but don't worry—this article isn't about that you just need to first master them and you will become web dev. I am assuming that if you want to do web development, your final aim is to learn how to create web applications or websites—basically something that will be running in a browser. And here is the first question: How browsers work? What happens "behind the hood" when you open your browser and homepage shows on your screen? How does your browser manage to display all the web sites you visit? You may be aware of the fact that most of the web applications have a "backend" that is residing on some mysterious "servers". And here is the second question: What exactly are the "backend" and "server," and how does a browser communicate with a "server"? Which code is considered "frontend," and which is "backend"? What determines whether some code belongs to one or the other? If you cannot answer these question, that's the "Somewhere Else" when starting with web development—by finding the answer to them. In this article I will provide the answers to these questions illustrating answers with hands on code examples. I will be writing code in a very direct way—no IDEs, no frameworks, no extra stuff. Just a browser, my PC's Linux OS, and basic JS and HTML. Because I also want to show you that you can do many things with just basic tools and that only your imagination is the limit. You don't need React, Nginx, Express, Angular, VSCode Live Server or something else to start trying some web development. In web development, there's front-end and back-end development. Even if you've already decided to focus on one, that doesn't mean you can completely ignore the other; you must know at least the basic ideas and how both "branches" work—front-end and back-end. For those who already followed some tutorials, taken some courses, and developed a beginner project, but the question remains: do you really understand how code—like HTML, CSS, or JS that you have ever written—ended up in a browser? You most probably have used an IDE, let's say VSCode, wrote some files as .html, .css, or .js, opened in a browser http://localhost:12345 (or any other port), and saw the result of what you coded. But how all these separate modules resulted into some fancy interactive page in your browser? So, let's start! NB! I use Linux, more precisely Debian, and I have an allergy to any other OS. So, if you use Windows or macOS, you might need to google how to do the same things on your system. Anyway, whatever I do in this article is not related in any way to the type of Operational System. Here is the roadmap of this article: ➀ Building confidence with a browser ➀.➀ Open random files in your browser to see what happens. ➀.➁ Browser's Developer Tools as an IDE (Integrated Development Environment) ➁ How does a browser work? ➁.➀ What is the document? ➁.➁ Browser's rendering engine ➁.➂ Document Object Model - DOM ➁.➃ Browser's JavaScript Interpreter ➂. Browser's Networking Layer and URLs ➂.➀ URI, URL and HTTP(s) protocol ➂.➁ What is a "server"? ➂.➂ Frontend vs. Backend: Understanding the Difference ➃. JavaScript potential (using Python as a proxy) ➃.➀ Node.js as JS Interpreter ➃.➁ Node.js REPL ➄. Hands-On: two approaches for getting JS output into the Browser (Frontend Logic vs. Backend Logic) ➄.➀ ➄.➁ Node.js Server App ➀ Building confidence with a browser If before web development you were just a user of your preferred browser, that golden time is over—now it's your working horse if you're aiming to be a front-end developer. As a user, you might be very picky about browsers, choosing one that suits you. But the moment you decide to do front-end, hehe, soon you will install all the most common browsers for testing purposes—at least one per engine group they use (yes, even Microsoft Edge). I'll explain why later. So, the browser... Now, I am writing this article in the browser. In a tab I am working I see in the address bar something like this: https://dev.to/dev-charodeyka/where-to-start-in-web-development-bla-bla/edit And if I go to any other webpage, I'll see something like: https://some-site/home You may have noticed that you can use your browser not only just to view web sites, but also to open images, PDF files, and other types of files. Fo

Dear reader, if this is your n-th article in search of an answer to the question imposed in its title—and you don’t want to waste your time—the answer is: Somewhere Else. Why? The key phrase here is "where to start". If you’re just discovering web development field and want to begin somewhere, starting with any of these frameworks (React, Svelte, Vue and Angular are frameworks)—will only confuse you, because they’re definitely not the tools to start with web development. In this article, I will uncover what is behind this Somewhere Else.

Even though, of course, HTML, CSS, and JavaScript (further - JS) are the fundamentals of web development, but don't worry—this article isn't about that you just need to first master them and you will become web dev.

I am assuming that if you want to do web development, your final aim is to learn how to create web applications or websites—basically something that will be running in a browser.

And here is the first question:

How browsers work? What happens "behind the hood" when you open your browser and homepage shows on your screen? How does your browser manage to display all the web sites you visit?

You may be aware of the fact that most of the web applications have a "backend" that is residing on some mysterious "servers".

And here is the second question:

What exactly are the "backend" and "server," and how does a browser communicate with a "server"? Which code is considered "frontend," and which is "backend"? What determines whether some code belongs to one or the other?

If you cannot answer these question, that's the "Somewhere Else" when starting with web development—by finding the answer to them.

In this article I will provide the answers to these questions illustrating answers with hands on code examples. I will be writing code in a very direct way—no IDEs, no frameworks, no extra stuff. Just a browser, my PC's Linux OS, and basic JS and HTML. Because I also want to show you that you can do many things with just basic tools and that only your imagination is the limit. You don't need React, Nginx, Express, Angular, VSCode Live Server or something else to start trying some web development.

In web development, there's front-end and back-end development. Even if you've already decided to focus on one, that doesn't mean you can completely ignore the other; you must know at least the basic ideas and how both "branches" work—front-end and back-end.

For those who already followed some tutorials, taken some courses, and developed a beginner project, but the question remains: do you really understand how code—like HTML, CSS, or JS that you have ever written—ended up in a browser? You most probably have used an IDE, let's say VSCode, wrote some files as .html, .css, or .js, opened in a browser http://localhost:12345 (or any other port), and saw the result of what you coded. But how all these separate modules resulted into some fancy interactive page in your browser?

So, let's start!

NB! I use Linux, more precisely Debian, and I have an allergy to any other OS. So, if you use Windows or macOS, you might need to google how to do the same things on your system. Anyway, whatever I do in this article is not related in any way to the type of Operational System.

Here is the roadmap of this article:

➀ Building confidence with a browser

- ➀.➀ Open random files in your browser to see what happens.

- ➀.➁ Browser's Developer Tools as an IDE (Integrated Development Environment)

➁ How does a browser work?

- ➁.➀ What is the

document? - ➁.➁ Browser's rendering engine

- ➁.➂ Document Object Model - DOM

- ➁.➃ Browser's JavaScript Interpreter

➂. Browser's Networking Layer and URLs

- ➂.➀ URI, URL and HTTP(s) protocol

- ➂.➁ What is a "server"?

- ➂.➂ Frontend vs. Backend: Understanding the Difference

➃. JavaScript potential (using Python as a proxy)

- ➃.➀ Node.js as JS Interpreter

- ➃.➁ Node.js REPL

➄. Hands-On: two approaches for getting JS output into the Browser (Frontend Logic vs. Backend Logic)

- ➄.➀

- ➄.➁ Node.js Server App

➀ Building confidence with a browser

If before web development you were just a user of your preferred browser, that golden time is over—now it's your working horse if you're aiming to be a front-end developer. As a user, you might be very picky about browsers, choosing one that suits you. But the moment you decide to do front-end, hehe, soon you will install all the most common browsers for testing purposes—at least one per engine group they use (yes, even Microsoft Edge). I'll explain why later.

So, the browser... Now, I am writing this article in the browser. In a tab I am working I see in the address bar something like this:

https://dev.to/dev-charodeyka/where-to-start-in-web-development-bla-bla/edit

And if I go to any other webpage, I'll see something like:

https://some-site/home

You may have noticed that you can use your browser not only just to view web sites, but also to open images, PDF files, and other types of files. For example, I don't have any PDF reader on my system, so I use the browser to view PDF files if needed.

➀.➀ Open random files in your browser to see what happens

Okay, so I open LibreOffice, drop some random text, and save it as a PDF on my PC and... I open it in the browser by typing in the address bar: file:///home/lalala/Projects/DEVTO/webdev/randomPDF.pdf.

Little remark: pay attention to how a local file stored on my PC is opened in the browser vs how websites are opened— "file:///home/lalala/..." vs "https://some-site/home..". Do you notice the same syntax? The key part to notice is: https:// and file:// (third / in file:///home/lalala/... belongs to the absolute path of the file). It is important, I will return to this later in the article.

And here is what I see when I open a randomPDF.pdf file in my Browser:

What if I want to view a text file with the same content instead of a PDF?

# first, I create it

$ vim randomTXT.txt

Hellow!

I am a TXT file!

I am visualized in a browser!

Then I paste this into browser's address bar to open text file: file:///home/lalala/Projects/DEVTO/webdev/randomTXT.txt

As you can see, the text is just text—there’s no bigger font for a title line, because the TXT format does not provide any way to format/style the text... but a Hyper*Text **Markup **L*anguage does—let’s create one!

# first, I create it

$ vim randomHTML.html

Hellow!

I am a TXT file!

I am visualized in a browser!

I paste this into browser's address bar: file:///home/lalala/Projects/DEVTO/webdev/randomHTML.html

Here is the result:

Let's add some spice - styling of one word with Cascading Style Sheets - a style sheet language used for specifying the presentation and styling of a document written in a markup language:

$ vim randomHTML.html

Hellow!

I am a random HTML file!

I am visualized in a browser!

Result:

I demonstrated HTML and CSS in action. If I want to display more text or change the color of some words, is modifying randomHTML.html file and then refresh the browser's page to see the changes is the only way to do it? Heh, of course not.

➀.➁ Browser's Developer Tools as an IDE (Integrated Development Environment)

First, I have to open the developer tools (hereafter, "dev tools") in my browser. If you're not sure how to open dev tools, you can easily find instructions online. A common method is to right-click anywhere on the page and select "Inspect" from the drop-down menu; however, this option may not always be available, as some websites block it. In that case, you can launch the dev tools from your browser's control panel, where you also can check a specific keyboard shortcut they are usually tied to.

This is how my chromium based browser Brave dev tools look like (the quality of screenshot is not the best due to the automatic compression of DEVTO attachments):

Development tools of my Brave browsers are grouped into Elements, Console, Sources, Network, Performance, Memory, Application, Security. I add/delete/modify HTML elements from Elements Tab.

Development tools of my Brave browsers are grouped into Elements, Console, Sources, Network, Performance, Memory, Application, Security. I add/delete/modify HTML elements from Elements Tab.

Using dev tools I can add/delete/modify HTML elements and CSS styles for them "on the fly". Of course dev tools are a pretty powerful tool and are not meant only for these silly modifications, but I just wanted to demonstrate how you can easily experiment with HTML and CSS directly from a browser.

However, keep in mind that whatever I do with the browser’s dev tools doesn’t affect the original .html file that I opened in the browser—all changes will be lost if I don’t save them into a separate file. The same is true for any web page you inspect with dev tools and eventually modify something - of course it does not affect permanently the original page in any way.

Okay, I played a bit with HTML and CSS from Elements tab of dev tools. There’s another interesting tab in these tools called Console, which is an interactive shell where I can write some JS code and execute it!

Some silly "print" of the sum of two numbers and a couple of evaluations of expressions:

//JS code I ran in the Browser's console:

const a = 2

const b = 3

a>b

a===b

aAnd you know what? Why not add a new HTML element to the displayed .html file's content opened in a browser with JS? Because JS is definitely capable of it:

//JS code I used to add a new text to my HTML document:

//first, I add

const newRandomDiv = document.createElement('div');

//then, I add child of , with some text

newRandomDiv.innerHTML = '

Hellow, I was added by JavaScript!!!';

//my HTML document has the

, so I append new element as a child of it

document.body.appendChild(newRandomDiv);

However, you might ask: what is the document? I opened the Console of dev tools and haven’t declared any document variable or anything like that—where does it come from? I guess it’s obvious that the document in question is related to the HTML file that’s open in the tab:

➁ How does a browser work?

On the screenshot above, you can see that I used the browser’s JavaScript interactive shell to "print" the document. From the output it is clear that it contains HTML elements from the original .html file I opened in the browser, plus some other elements that I added manually by directly editing the HTML structure in the dev tools and also using JavaScript from the browser. However, what was not originally in the randomHTML.html file that I opened are the tags like

The

The

➁.➀ What is the document?

Everything, that is enclosed between document. And, roughly speaking, that is what web development (front-end part) is about: working on this document - bending it, mangling it, shaping it to make it look how you want. When I opened randomHTML.html file with the browser I loaded this file into the browser, and its content became a part of document object.

When an HTML document is loaded into a web browser, it becomes a document object.

The document object is the root node of the HTML document.

The document object is a property of the window object.

The document object is accessed with: window.document or just document (W3Schools: HTML DOM Documents)

What about the TXT and PDF files that I opened before? Well, their content also become a part of document objects, when I open them in the browser.

This is the .txt file opened in my browser when I inspect the tab's content with dev tools:

Hellow!

I am a random TXT file!

I am visualized in a browser!

You may notice how interestingly the raw text file content was "wrapped" into an HTML document object by my browser. It is not uncommon for modern browsers to create a minimal HTML "wrapper" for a content that a browser was requested to display and that it managed to recognize.

In the plain text file, there was no any styling, like the first line in bold and enlarged font. But content of the .txt file has the line breaks. They were preserved by the browser by attaching CSS rules for word-breaking, white space, and word wrapping!

Let's have a look on the document object structure of PDF file opened in the browser:

What is similar to a .txt file is that the browser’s PDF viewer is embedded in a minimal HTML document. While with a text file I was able to see the actual file's content directly and even modify it right from the browser, with a PDF file it's not the same. This kind of embedding is actually a byproduct of how my browser handles and renders PDF files.

Can I mess it up with how PDF file is displayed using dev tools even if it is originally PDF file? Sure:

Here is JS code I used:

const redThingy = document.createElement('div');

redThingy.style.backgroundColor = 'red';

redThingy.style.width = '400px';

redThingy.style.height = '400px';

redThingy.style.position = 'absolute';

redThingy.style.top = '50%';

redThingy.style.left = '50%';

redThingy.style.transform = 'translate(-50%, -50%)';

redThingy.innerHTML = 'Hello, I was added by JavaScript to mess up PDF!!!';

document.body.appendChild(redThingy);

However, obviously, this red box with text didn’t affect the PDF file itself in any way. What my modifications actually affected was just how my browser rendered the opened PDF file.

I guess it’s time to summarize the point of all of these experiments.

As you can see, a browser is a powerful tool. It's not just an "app" to open websites with added features like a photo viewer or PDF viewer.

➁.➁ Browser's rendering engine

Any browser has its own engine that renders what you see on its User Interface (UI). Roughly speaking, to render anything a browser uses instructions in a markup language—HTML.

Different browsers work differently. However, let me explain the process slightly generalizing:

- When you enter a query in the browser's search bar (a URL), networking layer of the browser delivers your "request" to a destination point that is retrieved from URL and bring back to browser a response which could be any type of file or data. Some file types can’t be displayed directly (for example, if the file is corrupted or has an unrecognized format), in which case the browser may display an error or prompt you to download it instead.

- If the received data is recognized as HTML, the browser parses it to build a Document Object Model (DOM) tree. This process involves reading the HTML and turning it into a structured hierarchy of nodes that represent the page’s elements. If the received data isn’t HTML but the browser can still display it (like plain text or PDF), the browser will process it in a specialized way. For plain text files, most browsers apply a minimal HTML “wrapper”; for PDFs, the browser’s PDF viewer is embedded in within an HTML context, so browser can position it, handle scrolling, zoom, and so on.

- The browser then creates or updates a render tree, which is the combination of the DOM and the CSSOM (the CSS Object Model). The layout step figures out the exact positions and sizes of all elements on the page.

- Finally, the browser paints (or “rasterizes”) the render tree onto your screen. This is what you actually see in the browser’s viewport.

There are many variables in the rendering process. Every element in the DOM tree is an object that the browser needs to render by calculating its position (this is where responsive design comes in, since an element’s positioning depends heavily on the available space on the user’s device), appearance, and any dynamic changes. The DOM tree isn’t static; the browser continually re-renders it as elements move or change appearance—like those animations you see on some websites.

➁.➂ Document Object Model - DOM

I want to elaborate more on the DOM tree.

The backbone of any HTML document is its tags. In the Document Object Model (DOM), every HTML tag is an object. Nested tags are considered “children” of the enclosing tag, and even the text inside a tag is treated as an object. The DOM represents HTML as a tree structure of tags. (Source)

...

...

<...>...

You can notice the nested structure of HTML document: each tag is an object, and the nesting forms a tree-like hierarchy.

I'm repeating this: if you're aiming to be a front-end developer, the DOM is everything. In front-end development, almost everything ultimately revolves around DOM manipulation. I've shown how to manipulate the DOM using browser's dev tools—adding HTML elements, applying CSS, and most importantly, doing it through JS. Because in front-end development, JS is primarily about manipulating the objects in the DOM tree, which are (at their core) HTML elements.

All these DOM objects are accessible via JavaScript. I’ve only shown a small part, and it might have seemed very easy. Well, it was easy because I was working directly with those DOM objects—there were only a few, and everything was clear.

But remember this: the JS libraries you use to “simplify” certain features—and especially any framework (React, Angular, Vue, etc., though each to a different extent)—actually take you one step further away from direct manipulation of the DOM objects.

Frameworks abstract direct DOM manipulation, so you write your code in a more declarative way. Behind the scene, any framework still manipulates the DOM — but you interact with a framework’s abstractions instead of directly selecting or updating DOM elements.

The key point is that these abstractions are not "bad" - they make development more efficient and your code more maintainable, as long as you have a basic understanding of how the DOM works. If you rely on abstractions without knowing what’s happening underneath, you are cooked. No fancy framework will make you a good developer if you don’t at least keep the DOM tree in mind whenever you manipulate it with JS.

I’ve shown how to do manipulate DOM directly in the browser—not to promote this style of coding (obviously, no one codes like this for a full project). I just wanted to show you what your browser is truly capable of. Everything I did was handled entirely by the browser—there was no server behind it, no external tools, just the browser.

➁.➃ Browser's JavaScript Interpreter

And this leads to a very important point: I was able to execute JavaScript in the browser because browsers have a built-in JavaScript interpreter. Think about it—if you’re a Python developer, before you could run Python code, you had to install Python on your PC (unless you're on Linux, where it's usually pre-installed). That’s because Python isn't machine code, so your PC can’t understand it without an interpreter. The same goes for JavaScript. The key point is that modern browsers come with a JavaScript interpreter embedded in their engine.

Sounds great, right? But here’s the cornerstone: different browsers have slightly different JavaScript interpreters inside their engines. For basic, standard JavaScript usage, this isn’t a big deal. But when you get into non-standard usage, things get trickier. And every external library you add to your code potentially brings you slightly closer to using a JS in "non-standard" way that may be not supported by some browsers. And these browsers may be the favorite browser of potential users of your web applications :).

To conclude, here is a very generalized scheme of how browsers work:

Now, I will elaborate further on the format of "query" that is in the schematic search bar, as well as on role of "servers".

➂ Browser's Networking Layer and URLs

As I showed in the diagram, the query is processed by the browser’s networking layer, and it’s sent to a suitable server whose name matches part of that query. Here’s an important note: networking (in IT) is a difficult field. There’s no simple, quick way to cover all the basic networking concepts you’ll eventually need as a web developer. You’ll have to explore this area sooner or later—don’t worry, you’ll feel the urge to do it eventually, especially when you start wanting to host your projects.

If you’re interested, I can take a look at my article on Networking. Although it might be more advanced than strictly necessary for basic web dev, it can still be useful if you’re curious about networks, IP addresses ecc.

Leaving the deeper networking theory aside for now, I just want to focus on the format of the query. As mentioned, the browser’s networking layer takes part of that query and locates a right server based on it, sends a request there and then delivers a response if there is one. But how? And remember when I was opening files stored on my PC in the browser? It didn’t seem that "query" contained some "address" of my PC at all, right?

➂.➀ URI, URL and HTTP(s) protocol

Well, that’s because a request can be sent using different protocols. And you actually instruct the browser how to send that request all the time—maybe without even realizing it.

Whenever you type a query to visit a specific website you know by URL—say, google.com—you put https://google.com in the search bar. (Often, the browser automatically prepends https:// if you just type google.com.) If you want to open a file in your browser, you can type something like file:///some/path/file.txt.

Notice that anything before :// is a protocol. When you use the file:// protocol to open local files, you don’t need to specify any particular "address" of your PC if you’re just opening a local file. On the other hand, the http(s):// protocol does require an address (and additional parts), which I’ll explain next.

I first want to elaborate on this magic word "URL", which is used so freely not only by developers but also by just users.

Actually, there isn’t just "URL"; there’s also "URI".

Uniform Resource Identifiers (URI) are used to identify "resources" on the web. URIs are commonly used as targets of HTTP requests, in which case the URI represents a location for a physical resource, such as a document, a photo, binary data.

The most common type of URI is a Uniform Resource Locator (URL), which is known as the web address.

A Uniform Resource Name (URN) is a URI that identifies a resource by name in a particular namespace. (MDN web docs: URIs)

The point is that a URL ∈ URI (is a subset of), meaning a URI is broader.

For example, file:///home/lalala/Projects/DEVTO/webdev/randomPDF.pdf

is a URI, but not a URL because the protocol is file: rather than http:.

By contrast, http://www.example.com:80/path/to/myfile.html?key1=value1&key2=value2#SomewhereInTheDocument is both a URI and a URL.

Let's decompose this URL:

-

http:// is the scheme of the URL, indicating which protocol the browser must use

-

www.example.com is the host name of the URI, indicating which Web server is being requested. Here, we use a domain name. It is also possible to directly use an IP address, but because it is less convenient, it is rare to do so, unless the server doesn't have a registered domain name

-

:80 is the port of the URL, indicating the technical "gate" used to access the resources on the web server. It is usually omitted if the web server uses the standard ports of the HTTP protocol (80 for HTTP and 443 for HTTPS) to grant access to its resources. Otherwise, it is mandatory.

-

/path/to/myfile.html is the path of the URL, indicating the location of the resource on the web server. In the early days of the Web, this was an actual directory path to a physical location on the web server. Nowadays, web servers usually abstract this to an arbitrary location.

-

?key1=value1&key2=value2 is the query of the URL, which are extra parameters provided to the web server. The parameters are a list of key/value pairs prefixed by the ? symbol, and separated with the & symbol. These can be used to provide additional context about the resource being requested.

Summarizing the main point: The URL you place in the browser’s search bar indicates the address of a "resource" from which the browser should fetch something and then, upon successful retrieval, "paint" it on the UI for you—assuming what’s retrieved is displayable.

➂.➁ What is a "server"?

That "resource" is typically a server. However, "server" is an ambiguous term because, in my diagram, I called "server" a computational device connected to the global network (with storage to hold data and "serve" it upon request) a server. It could be your personal PC, a laptop, a Raspberry Pi—whatever. We usually refer to it as a server because, when you’re doing serious web development, you can’t just store your production-ready web application on any personal PC.

Anyway, the difference between a "server" machine and a typical PC is that server machines are usually more powerful (though not always) and, most importantly, are designed to run 24/7, unlike a normal PC. They also usually have no GUI and often look like those "black boxes" I showed in the diagram.

So why "server" term is ambiguous? Because, besides physical servers, there’s also software known as a server. This software is called a server because its purpose is to serve something. For instance, the entire user interface on my PC—like the desktop environment—runs on a display server installed on my Debian OS. Without it, I’d have only a terminal, just like on many headless servers. Similarly, there’s a sound server on my Debian OS that manages input and output for audio devices.

In web development, we have a web server, which is software running on any physical computing device. Its job is to serve any requests sent by clients - browsers of users.

Now, you might be confused because it seems like everything is related to "servers", which might make you think it’s all about the backend—so where does the frontend come into play?

➂.➂ Frontend vs. Backend: Understanding the Difference

It’s important to keep in mind that when you put a URL in the search bar, it goes to the address specified in that URL and retrieves whatever is served there—literally anything.

_It’s like a request you might get from a friend saying, "Please go to my house, here’s the address. Go to my room, open the red wardrobe, and bring me everything from the purple box you find". When you get that request, you have no idea what’s actually in there—are the items big or small, heavy or light, etc.? What if the purple box is huge or doesn’t exist at all? What if there’s no red wardrobe, or if the house itself doesn’t exist at that address? What if you can’t even enter because you need a key?

But if everything works out, you grab the box, empty it and carry all the items to your friend, previously packing them in your pockets, backpack or whatever (up to you), and obviously see whatever’s inside it—there’s no way to hide that from you._

This is analogous to the frontend. The browser (the client) has to request content from the server to display it, since the browser can’t store all the web pages in the world by itself (not even just their home pages). However, browsers do have some storage.

Returning to the analogy: let’s say your friend is always asking you to fetch his keys from home because he keeps forgetting them. One day he might say, "Just keep them with you. There’s no point in going back to my house every time".

This is a parallel to the browser cache. Some websites store certain data in your browser, so the next time you visit, that data is already there—no fresh request needed. Of course, as you can imagine, if you visit many sites, each storing something in your browser, it can become huge very quickly. But that’s simply how it works.

So, what is the difference between the frontend and the backend, given that it all relates to servers?

Remember that your browser fetches data from a given address—files for rendering the DOM tree and then painting it on screen. The server provides the necessary instructions—HTML, CSS, and maybe JS ( which browser should execute!). This is all in plain sight, with nothing truly hidden, because the browser has to build the tree, display elements in the right place, and attach the required functionalities and styles. Technically, if you open dev tools (as I showed earlier), you can inspect and see everything the browser has loaded from a specific website.

But let’s talk about authentication as an example. As a developer, you need to know whether a user is authenticated or not, because that might give them access to certain functionalities or show them a different UI. All your browser needs is a simple "yes" or "no" to confirm authentication status and do rendering base on this condition—it doesn’t need the user’s password or other private info. Why? Because anything sent to the browser is visible in dev tools anyway.

And that is where the backend comes in. Yes, it sits on the server, and it can be written in any language you want, since the browser doesn’t compile or execute that code—it never even receives the backend source code in the first place. What does the browser get instead? Data—often in JSON format, which could be “yes/no,” “1/0,” some array or list, or whatever else you decide to send.

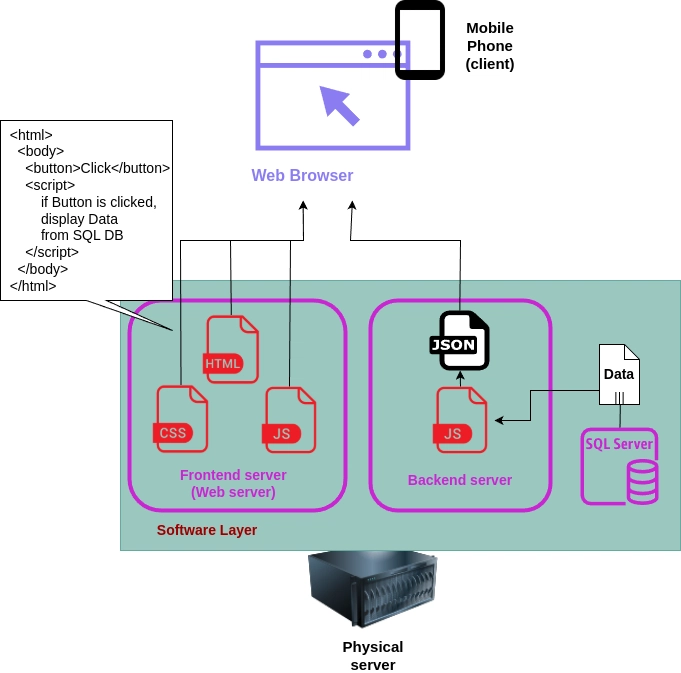

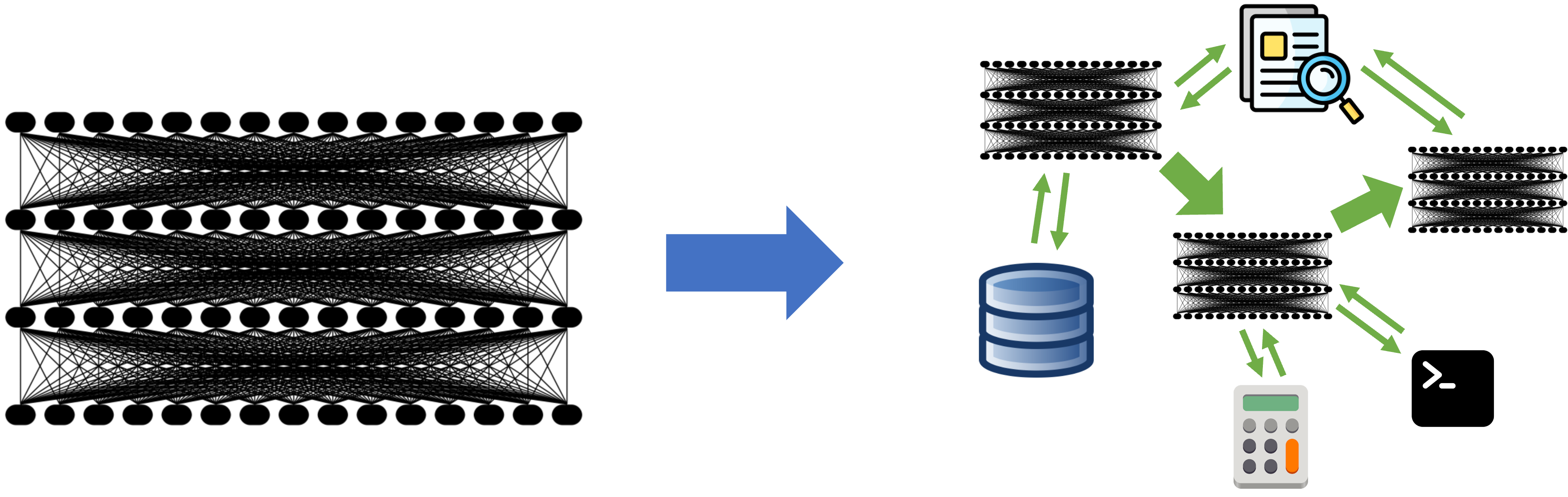

Here is another schematic representation:

As you can see, on a physical machine (the server), you might have three servers running at once: a web server, a backend server, and an SQL database server.

When a user visits a website served by these three components, their request first goes to the physical server to retrieve the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript from Web server needed to render let's say the home page. Then, suppose there’s a button on that page. If the user clicks it, they need to see some data from the SQL server—for instance, a list of cities that have shops.

And here’s where the backend enters the picture. The button on the frontend has some JavaScript code attached, but this frontend JS simply calls the endpoint of backend server, and on this endpoint another JS script is residing. That backend script is never visible on the frontend; it only returns the data it retrieves from the database. Once that data is returned to the browser, it triggers the browser to update the DOM—maybe by inserting a new to display the data in plain JSON or any other format that was specified.

On the scheme, I showed that data from the database is retrieved by JS code that’s part of the backend server. As I mentioned earlier (and as you may already know), the backend can be written in various languages—Python, Rust, PHP, JavaScript, Go, and so on. However, I want to focus on JavaScript as a backend language...because why not? First, it’s great for lazy people like me who don’t want to maintain two different codebases in two different languages (especially if they have different optimal data structures). I enjoy having both frontend and backend in JS. And if you also don’t mind using JavaScript as a backend language, then you’ll need a JS interpreter on the backend side.

If this isn’t clear yet: if you work on a small project that you develop from scratch on your PC (in the development stage), your browser is the client, and the frontend code is intended for it. Meanwhile, your PC/laptop also acts as the server—meaning you need to have the web server, backend server, and (if needed) a database server, all running on that same machine.

And if browsers have built-in JS interpreters, you can also install a JS interpreter on your PC. Having a JS interpreter on your machine is essential for actually practicing JS. I want to elaborate on this because, in my experience, some developers are reluctant to treat JavaScript like a "real" programming language—assuming it’s only for superficial frontend stuff. That’s a myth. If you’re a Python dev, for example, you can use JS just like you use Python. The next section will offer examples to prove this point.

➃. JavaScript potential (using Python as a proxy)

I cannot know for sure, but let me base my explanation on the assumption that you're coming to web development with some background in Python (or any other programming language). And using your knowledge of Python as a proxy, you're somehow comfortable with JS when you encounter a code written in this language.

In Python, you write some code in a file with the extension .py—let's say some_cool_script.py—and then run it with:

$ python3 some_cool_script.py

It prints something to the console, or silently does something—maybe creates another file or whatever. Also, when you just want to do something quickly, you can open the interactive Python console, or more correctly you can invoke Python interpreter:

$ python3

Python 3.13.2 (main, Feb 5 2025, 01:23:35) [GCC 14.2.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import os

>>> a = 2

>>> b = 3

>>> print(a+b)

5

>>> exit()

$

So, if you've NEVER used JS in the same way and have no idea how to do it, this is where to start. JS is not some mysterious creature to be used only in browsers. It's a programming language, and you can use it just like you use Python! You don't need a web server, browser, etc., to run JavaScript code. However, you do need something... JavaScript Interpreter.

If your PC is on Linux, chances are that the Python interpreter is preinstalled, so you usually don't have to install anything to execute Python code. On Windows, however, you'll need to install Python Interpreter. In the case of a JavaScript, its interpreter doesn’t come preinstalled on either Linux or Windows. So, first, you have to install it.

Here's something important to understand: with Python, things are a bit different—the language is called Python, and its interpreter (or, in technical terms, its runtime environment) is also called Python. However, whether or not Python is installed on your PC, what’s installed isn’t the programming language itself; it’s the runtime environment for Python that’s crucial to have on your machine. Your PC doesn’t understand Python code natively; it only understands machine code. In order for your PC to run Python code, it needs to convert that code into machine code. All that allows your PC to do this is bundled into "Python runtime environment".

➃.➀ Node.js as JS Interpreter

The same principle applies to JS. JS needs a runtime environment to run IN, and that environment is called Node.js, which you have to install if it is not already installed.

If you already tried to do something with any framework (React for example), you have it installed. To check you can run following command:

$ node -v

v22.12.0 <--my output

If running this command you find out that there is no node installed, this is a pretty simple, official guide to installing Node.js:

You can select the version that is most suitable for you from the dropdown menus—choosing your OS, installation mode, etc. For example, I chose the following options:

-

Get Node.js®: v22.14.0 (LTS)

-

For: Linux

-

Using: nvm

-

With: npm

These options result in a couple of commands that you need to run to install Node.js. In my case they are:

# Download and install nvm:

curl -o- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nvm-sh/nvm/v0.40.1/install.sh | bash

# in lieu of restarting the shell

\. "$HOME/.nvm/nvm.sh"

# Download and install Node.js:

nvm install 22

# Verify the Node.js version:

node -v # Should print "v22.14.0".

nvm current # Should print "v22.14.0".

# Verify npm version:

npm -v # Should print "10.9.2".

And here is the JS code that I previously was running directly in the Python interpreter's interactive shell:

$ node

Welcome to Node.js v22.12.0.

Type ".help" for more information.

> const os = require('os');

undefined

> const a = 2

undefined

> const b = 3

undefined

> console.log(a+b)

5

undefined

> a === b

false

> a < b

true

> .exit

(Of course, in both code examples (Python and JS), the import of the built-in os module is unnecessary since it isn’t used—it’s just included for demonstration purposes).

➃.➁ Node.js REPL

You can get a bit confused by the undefined that automatically prints after many lines when I initialize variables and print something in the console. So, I've added a couple of lines that perform an evaluation — as you can see, they just output true or false with nothing undefined.

These undefined prints are due to the difference between Python Interactive Shell and Node.js REPL.

REPL stands for Read Evaluate Print Loop, and it is a programming language environment (basically a console window) that takes single expression as user input and returns the result back to the console after execution. (Node.js: How to use the Node.js REPL)

undefined prints are byproducts of the fact that user inputs in the Node interactive shell are treated as expressions rather than statements (as they are in the Python interactive shell). For example, when you enter a JS statement like const a = 2, its evaluation results in undefined. In contrast, a JS expression like a > b is evaluated and returns a defined value—either true or false.

Okay, anyway, both the Python interactive shell and the Node.js REPL are not the best choices for writing a structured code, but they're perfect for small tests of different pieces of code—especially if you're as lazy as I am.

I'm that lazy, so I can even launch some pieces of script in the terminal rather than writing them in a file and then launching them properly, hehe. With JS, you don't even need to care about indentation like in Python.

For example:

$ python3 -c "a=2; b=3; print(a+b)"

5

$ node -e "const a = 2; const b = 3; console.log(a + b);"

5

#Python and indentiation:

$ python3 -c $'a=2\nb=3\ndef sumAB(a,b):\n print(a+b)\n\nsumAB(a,b)'

5

#JS does not gaf about indentation:

$ node -e "const a=2; const b=3; const sumAB =()=> {console.log(a+b)}; sumAB();"

5

What does this silly command node -e "const a=2; const b=3; const sumAB =()=> {console.log(a+b)}; sumAB();"? it executes JS code on the "server side" (my PC) if to think about it in abstract way.

Let me show you one last important thing I mentioned before: with Python, you run your script by something like python3 some-cool-script.py for running Python scripts, or even larger, multi-module complex code by running python3 main.py and this main.py will call all other python modules.

Again, you can do the same for JS scripts/projects:

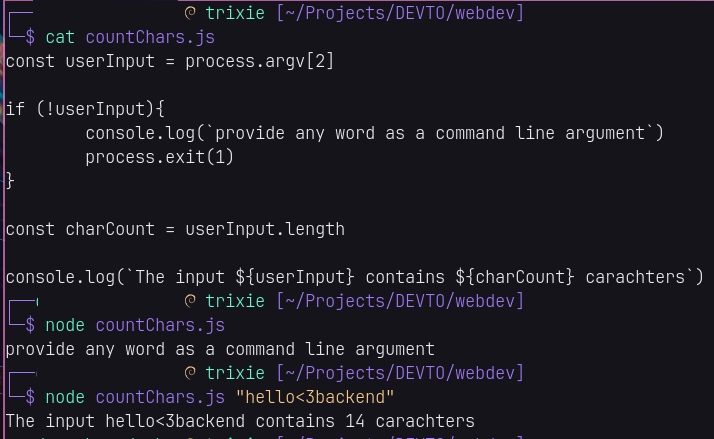

$ vim countChars.js

const userInput = process.argv[2]

if (!userInput){

console.log(`provide any word as a command line argument`)

process.exit(1)

}

const charCount = userInput.length

console.log(`The input ${userInput} contains ${charCount} characters`)

$ node countChars.js "hello<3backend"

The input hello<3backend contains 14 carachters

$ vim count_chars.py

import sys

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print("provide any phrase as a command line argument")

sys.exit(1)

user_input = sys.argv[1]

char_count = len(user_input)

print(f"The input '{user_input}' contains {char_count} characters")

$ python3 count_chars.py "hello<3pythonbackend"

The input 'hello<3pythonbackend' contains 20 characters

So at this point, as you can see—especially if you're mostly a Python dev—you can do many things in JS the same way you do with Python. You don't need React, Angular, Svelte, Vue, or whatsoever to do something with JavaScript, especially when you're just learning it. Node.js is all you need to get started with JS.

However, an important note: running "atomically" some JS scripts with Node.js is not truly a "backend", hehe. In common terms, backend development in web development usually comes down to creating a backend server (a constantly running application)—not just scripts that run once, but a constantly running app whose purpose is to serve the frontend (the "client" application that runs in the browser). Node.js is completely capable of running such a "backend" application for you, btw.

➄. Hands-On: two approaches for getting JS output into the Browser (Frontend logic vs. Backend logic)

So, in the examples above, I wrote a script that counts the characters of user input. It’s kinda atomic, let’s say—I can only get the JS output if I run it on my PC, where it resides, using the Node.js runtime. But what if I want to display the results of that character count not in my PC’s terminal, but in my browser instead? Now is finally the time to gather all the previously mentioned concepts about browsers, clients, servers, and so on.

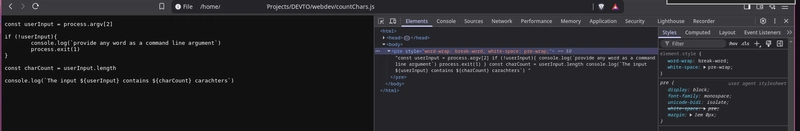

The browser has a built-in JS compiler, so it should be able to run it, right? What if I try opening my countChars.js script using the file:// protocol in the URI, pointing to the absolute path of the file on my PC—just like I did at the beginning with PDF and text files?

I insert this URI in my browser's search bar file:///home/lalala/Projects/DEVTO/webdev/countChars.js; and...

Ta-dam! Browser opened this script as if it was just a raw text file. The JS code itself gets wrapped in

I show this just for demonstration purposes about what happens when you open JS files in a browser. Anyway, this code would never have worked in the browser, because it strongly relies on the Node.js process.args module, which is meant for processing arguments passed via the command line interface—and such arguments don’t exist in the browser environment. So I have to modify it slightly.

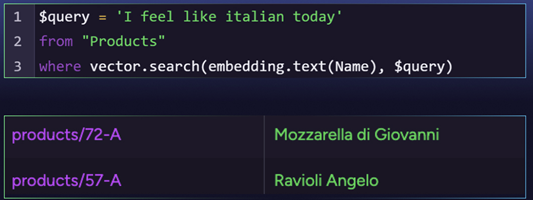

➄.➀

Here is the JS code I’ll feed to the browser to execute and run. The CLI argument role in the HTML code will be played by an input field and a submit button; once clicked, it should trigger this code, which will write its output into a pre-created .

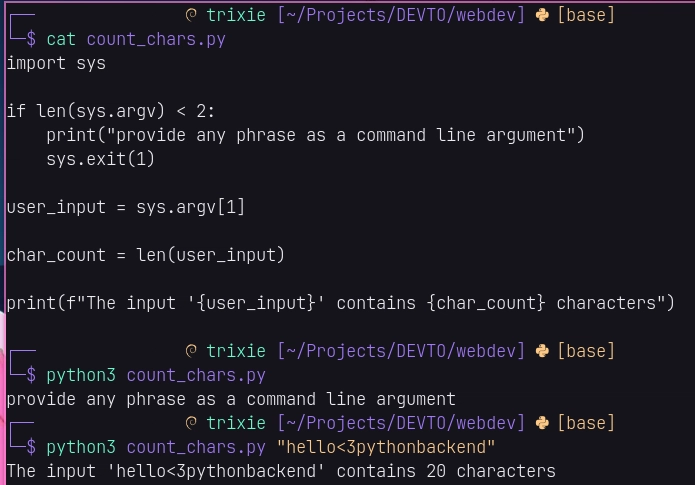

$ vim jsCharCounterFE.js

document.getElementById('submitButton').addEventListener('click', () => {

const userInput = document.getElementById('userInput').value;

const outputDiv = document.getElementById('output');

if (!userInput) {

outputDiv.textContent = 'provide any phrase';

return;

}

const charCount = userInput.length;

outputDiv.textContent = `The input "${userInput}" contains ${charCount} characters.`;

});

And here is the HTML file that I’ll open in my browser with the file:// protocol:

Character Counter

I simply paste file:///home/lalala/Projects/DEVTO/webdev/charCounter.html in my browser's search bar and voila:

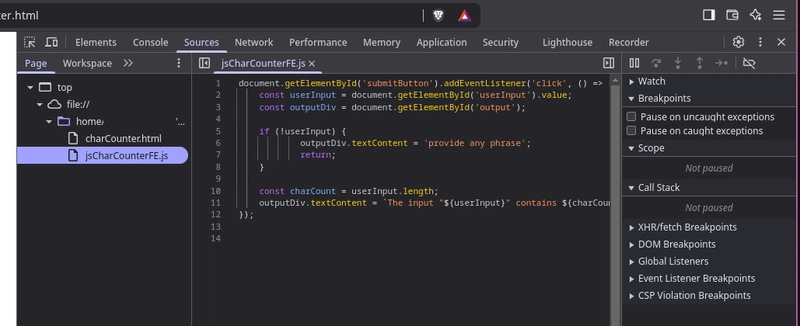

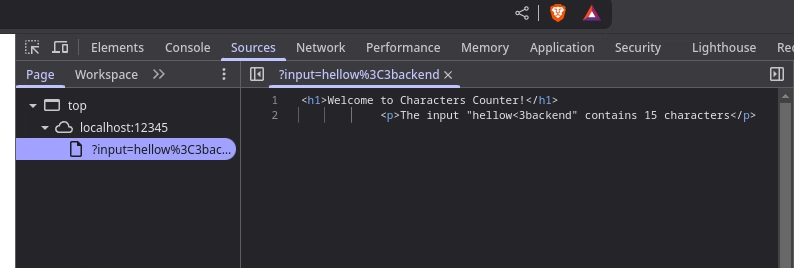

In DevTools, if I go to the Sources tab (as I mentioned), I can see all the source code, because both the HTML and JS were fully exposed to the browser—and that’s fine in this case, since there was no "secret" code to hide.

Also, as you may have noticed, I didn’t use any web server here, even though I talked about it a lot. That’s because I didn’t use the HTTP protocol to send requests; instead, I used a protocol that can directly access files.

But now there’s one last thing to tackle in this article: What if I wanted to do all of this with a backend? Because the backend isn’t only for sensitive code or information like credentials—it’s also important for performing heavy calculations that users’ devices might not handle well or quickly. For example, let’s say you have a database with one billion products. You could use your backend to retrieve 100,000 names and send them to the browser… but for what? To display them all at once? Probably not—nobody wants to see a huge list like that in the UI. More likely, there’s some logic for searching or filtering, so the frontend doesn’t need that entire data dump. That’s where dividing responsibilities between frontend and backend makes a lot of sense.

Maybe a decade ago, even simple operations would end up on the backend, because client devices—especially small ones like phones—were really weak. They’d struggle with heavy calculations. But the world has changed, and so have devices. My phone is more powerful than many old-generation server machines I’ve seen.

Important note: If you’re aiming to be a frontend dev because you think it’s "easier", or you’re aiming to be a backend dev because you assume the frontend is not serious or not enough challenging, you’re mistaken. Client devices are getting more and more powerful, so doing calculations and advanced logic on the client side is becoming normal. Relying on the backend for everything and using the frontend only for HTML and CSS might not be the wisest architectural choice.

So, let me demonstrate how I can serve the output of a character counter to the browser via a backend server.

If previously, I could serve files to the browser straight from the file system (using file://), this time that won’t work.

➄.➁ Node.js Server App

I need to define and start a tiny backend server—essentially a Node.js application—that keeps running and can receive requests via a URL from the browser’s address bar.

$ vim littleServer.js

//Node.js modules that I need for my little server

const http = require('http');

const url = require('url');

//I chose randomly port

const port = 12345;

//server itself - it accepts requests and sends responses

const server = http.createServer((request, response) => {

//remember query part of URLs? that starts with "/?"

const queryObject = url.parse(request.url, true).query;

//here I determine query format: /?input=<..>

const userInput = queryObject.input;

//output if no phrase is provided

if (!userInput) {

response.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' });

response.end('provide any phrase in the format /?input=');

return;

}

const charCount = userInput.length;

//output in HTML rather than plain text!

const output = `Welcome to Characters Counter!

The input "${userInput}" contains ${charCount} characters`;

//communications is via HTTP protocol, so I should respect the format of responses

response.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' });

response.end(output);

});

//this server is constantly listening, once started and until stopped

server.listen(port, 'localhost', () => {

console.log(`Little server is running on localhost port ${port}`);

});

Then, I just start this little Node.js backend server with:

$ node littleServer.js

Little server is running on localhost port 12345

How can I send a request to this server from the browser? How should I compose the query, and what is the address?

Well, here it is:

server.listen(port, 'localhost', () => {

console.log(`Little server is running on localhost port ${port}`);

});

My server is running on localhost—which is the loopback network interface on my PC. If I hadn’t specified 'localhost' and only set the port, then my Node.js backend server would have been serving any requests arriving at port 12345 on any network interface on my PC.

Yes, it can be hard to grasp the concept of network interfaces, but as I’ve mentioned, it’s unavoidable in web development to learn basics of networking. Essentially, what "network interfaces" means in this context is that if my silly app was exposed to the public internet (and I shared public IP address of my PC), you could have sent requests to it from anywhere and tried this silly app yourself.

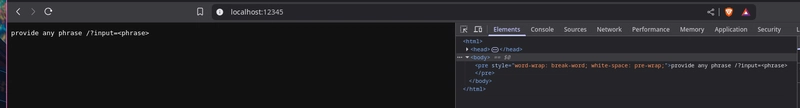

I start combining the URL: http://localhost:12345/. That’s all! Here’s what I see:

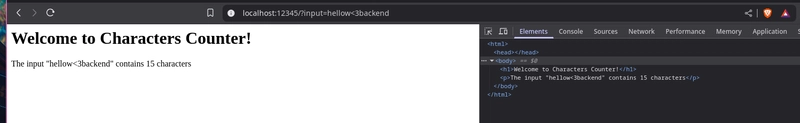

But if I really want to use the counter, I have to provide a phrase as input. I do this by appending a query to the URL, because my Node.js app expects it:

http://localhost:12345/?input=hellow%3C3backend.

Voila:

Question with an asterisk: Why does the first screenshot of the open tab content inherit the dark theme from the browser, while the second screenshot does not respect the dark theme?

Here is a proof that I cannot see a JS source code from browser:

Whoa, finally it’s done! Writing about web development is really tough because there are so many things you shall see live - this way is clearer than any screenshots. Still, this article was written somewhat from a particular perspective—mostly focusing on what can do what, how one application serves another, and so on.

Summarizing the main points:

- Browsers have a built-in JS interpreter and they do run JS code.

- The browser’s JS interpreter is not the same as your PC (or server)’s JS interpreter—they’re different. Keep this in mind.

- The internal components of browsers are complex, and each browser implements them differently. In my experience, that’s what makes the frontend part harder than the backend in modern architectures.

- You need to understand both backend and frontend to be a good web developer—you can’t just master one and completely ignore the other.

- If "network" for you only means "the Wi-Fi at home", you must refine your understanding of networking.

- Experiment with plain JS on your PC. If you’re not confident with JS, try writing more code in this language, including backend code. There’s nothing wrong with JS; it’s not inherently worse than Python, for example.

- Don’t overuse VSCode and its 1000000+ plugins that make web dev feel super easy. If you can only run your code or project from VSCode and have no idea how to start it otherwise (for example , it is VSCode, who settles for you port-forwarding, opens an app in the browser with right URI), that’s a red flag telling you to step away from VSCode for a bit.

- If you’re doing beginner tiny projects, especially without any backend, you don’t need any framework (React, Angular ecc).

![[The AI Show Episode 142]: ChatGPT’s New Image Generator, Studio Ghibli Craze and Backlash, Gemini 2.5, OpenAI Academy, 4o Updates, Vibe Marketing & xAI Acquires X](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20142%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The Premium Learn to Code Certification Bundle (97% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![From drop-out to software architect with Jason Lengstorf [Podcast #167]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1743796461357/f3d19cd7-e6f5-4d7c-8bfc-eb974bc8da68.png?#)

.png?#)

.webp?#)

_Christophe_Coat_Alamy.jpg?#)

(1).webp?#)

![Apple Considers Delaying Smart Home Hub Until 2026 [Gurman]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96946/96946/96946-640.jpg)

![iPhone 17 Pro Won't Feature Two-Toned Back [Gurman]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96944/96944/96944-640.jpg)

![Tariffs Threaten Apple's $999 iPhone Price Point in the U.S. [Gurman]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96943/96943/96943-640.jpg)