Virginia will use technology to slow chronic speeders’ cars—and other states are rushing to join in

Americans worried about their country’s sky-high rate of crash deaths haven’t had much to cheer lately. Although pedestrian fatalities remain near an all-time record, U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy wants to stop funding “active” transportation projects such as sidewalks. A prominent webpage encouraging safe street designs has disappeared, and layoffs have rocked the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the federal agency responsible for minimizing crashes. But at the state level, an encouraging trend is emerging. From California to Maryland, state legislators are exploring the use of new technology, known as Intelligent Speed Assist (ISA), that can prevent the most reckless drivers from blasting past the speed limit. Even at a time of entrenched political polarization, ISA has garnered bipartisan support. “It’s really growing much more rapidly than we anticipated,” says Amy Cohen, the head of Families for Safe Streets, a national advocacy group backing the various ISA bills. She and her allies hope to sidestep the Trump administration entirely, relying instead on states to promote the adoption of lifesaving car technology. The safety argument against speeding is ironclad. Blazing-fast vehicles take longer to brake and exert more force in a crash, thereby endangering everyone else on the roadway. Across the U.S., around 12,000 people died in speeding-related crashes in 2022, almost a third of the national total. “Super-speeders” going more than 20 mph over the limit can cause catastrophic harm. In 2022, a driver in North Las Vegas, Nevada, flew through an intersection at 103 mph, killing himself and eight other people. Despite the risks, super-speeding is disturbingly common. Last year, law enforcement in Rhode Island issued 292 tickets to drivers exceeding 100 mph, while Ohio’s highway patrol cited 38 people for doing so in a single day. Since police inevitably miss many infractions, super-speeders often get away with it. Automated speed cameras provide a more reliable means of enforcement, but their deployments are often mired in controversy. (Camera-based ticketing is banned completely in many states.) For the speeders who are caught, penalties may be limited to a fine or a driver’s education class. Even a license suspension doesn’t necessarily change behavior: A federally funded study found that 75% of people with suspended licenses continued to drive. Rather than relying on dubious ex post penalties, ISA systems make extreme speeding difficult or even impossible. The technology, which can be installed while a car is manufactured or afterward, uses GPS to identify the speed limit on a road segment and then deter drivers from going more than a programmed amount beyond it. “Passive” ISA systems issue tactile or audible warnings that attract the driver’s attention, while heavier-handed “active” systems block additional acceleration after the maximum threshold is reached. (ISA works through the gas pedal; it does not affect braking.) ISA has attracted growing attention from researchers, safety advocates, and policymakers. As of last year, the European Union requires all new cars to contain passive ISA. In the U.S., the National Transportation Safety Board has called on NHTSA to impose a similar ISA mandate, but the agency has shown no signs of doing so. Impatient with federal inaction, state leaders are taking matters into their own hands. Last year, California State Sen. Scott Wiener proposed a bill requiring ISA on all new cars sold in the Golden State. To the surprise of even many supporters (and to the consternation of the auto industry), Wiener’s bill passed both of California’s legislative chambers before Gov. Gavin Newsom ultimately vetoed it. Now, a new wave of state bills is advancing a narrower and seemingly less controversial application of ISA technology. Rather than call for passive ISA on all new cars, advocates are arguing that active ISA—which can make extreme acceleration impossible—should be placed on vehicles owned by people with a history of reckless speeding. Last year, the District of Columbia became the first jurisdiction to pass such a law. This spring, Virginia passed its own bill, which gives judges the option of requiring ISA if a driver exceeded 100 mph. Legislatures in Arizona, California, Georgia, Maryland, and New York are now considering their own proposals. (Proposals typically include a limited “override” feature allowing further acceleration during an emergency.) “The bills are all a little bit different,” Cohen says. “But they are all taking the worst drivers and saying that this technology has to be put in their cars for the duration that a license is suspended.” Politically, a focus on reckless drivers offers crucial advantages over a blanket ISA requirement like those that the EU has adopted and California has considered. Since only a small fraction of drivers are super-speeders (Cohen estima

Americans worried about their country’s sky-high rate of crash deaths haven’t had much to cheer lately. Although pedestrian fatalities remain near an all-time record, U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy wants to stop funding “active” transportation projects such as sidewalks. A prominent webpage encouraging safe street designs has disappeared, and layoffs have rocked the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the federal agency responsible for minimizing crashes.

But at the state level, an encouraging trend is emerging. From California to Maryland, state legislators are exploring the use of new technology, known as Intelligent Speed Assist (ISA), that can prevent the most reckless drivers from blasting past the speed limit. Even at a time of entrenched political polarization, ISA has garnered bipartisan support.

“It’s really growing much more rapidly than we anticipated,” says Amy Cohen, the head of Families for Safe Streets, a national advocacy group backing the various ISA bills. She and her allies hope to sidestep the Trump administration entirely, relying instead on states to promote the adoption of lifesaving car technology.

The safety argument against speeding is ironclad. Blazing-fast vehicles take longer to brake and exert more force in a crash, thereby endangering everyone else on the roadway. Across the U.S., around 12,000 people died in speeding-related crashes in 2022, almost a third of the national total.

“Super-speeders” going more than 20 mph over the limit can cause catastrophic harm. In 2022, a driver in North Las Vegas, Nevada, flew through an intersection at 103 mph, killing himself and eight other people. Despite the risks, super-speeding is disturbingly common. Last year, law enforcement in Rhode Island issued 292 tickets to drivers exceeding 100 mph, while Ohio’s highway patrol cited 38 people for doing so in a single day.

Since police inevitably miss many infractions, super-speeders often get away with it. Automated speed cameras provide a more reliable means of enforcement, but their deployments are often mired in controversy. (Camera-based ticketing is banned completely in many states.)

For the speeders who are caught, penalties may be limited to a fine or a driver’s education class. Even a license suspension doesn’t necessarily change behavior: A federally funded study found that 75% of people with suspended licenses continued to drive.

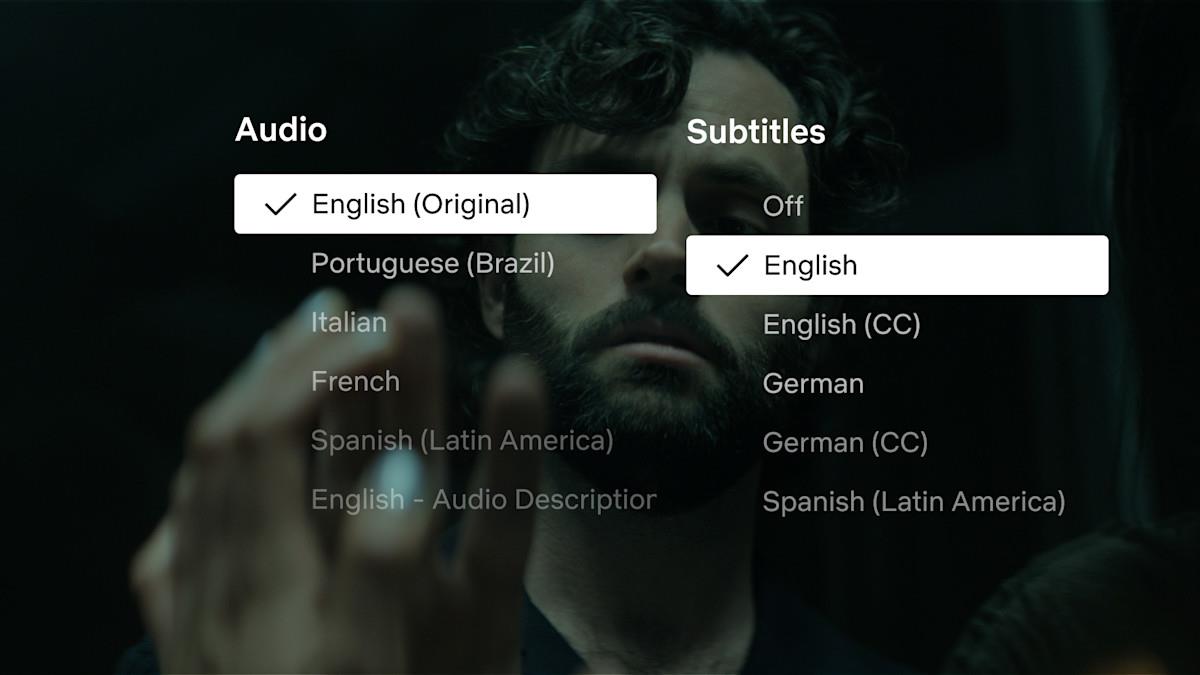

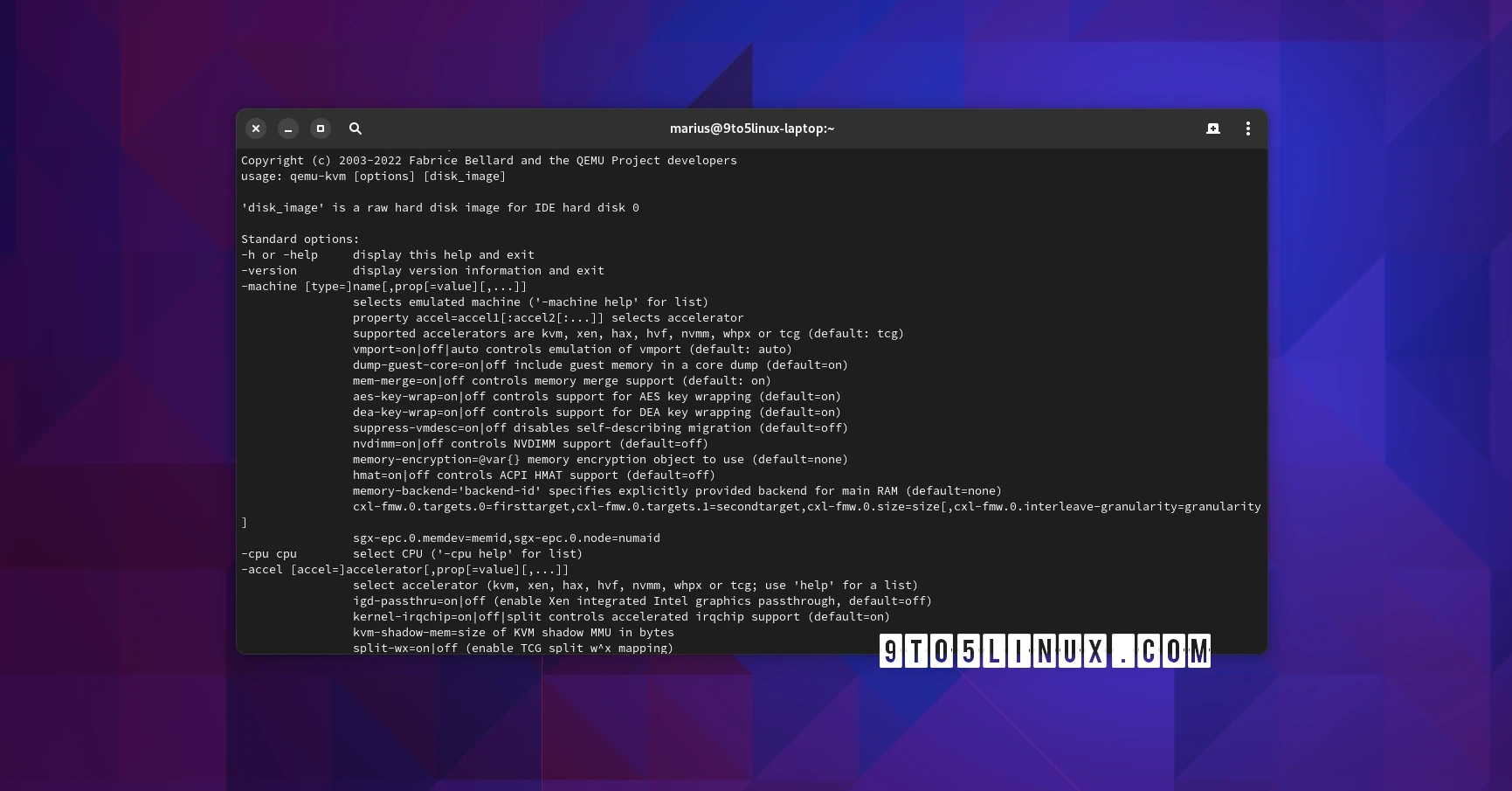

Rather than relying on dubious ex post penalties, ISA systems make extreme speeding difficult or even impossible. The technology, which can be installed while a car is manufactured or afterward, uses GPS to identify the speed limit on a road segment and then deter drivers from going more than a programmed amount beyond it. “Passive” ISA systems issue tactile or audible warnings that attract the driver’s attention, while heavier-handed “active” systems block additional acceleration after the maximum threshold is reached. (ISA works through the gas pedal; it does not affect braking.)

ISA has attracted growing attention from researchers, safety advocates, and policymakers. As of last year, the European Union requires all new cars to contain passive ISA. In the U.S., the National Transportation Safety Board has called on NHTSA to impose a similar ISA mandate, but the agency has shown no signs of doing so.

Impatient with federal inaction, state leaders are taking matters into their own hands. Last year, California State Sen. Scott Wiener proposed a bill requiring ISA on all new cars sold in the Golden State. To the surprise of even many supporters (and to the consternation of the auto industry), Wiener’s bill passed both of California’s legislative chambers before Gov. Gavin Newsom ultimately vetoed it.

Now, a new wave of state bills is advancing a narrower and seemingly less controversial application of ISA technology. Rather than call for passive ISA on all new cars, advocates are arguing that active ISA—which can make extreme acceleration impossible—should be placed on vehicles owned by people with a history of reckless speeding. Last year, the District of Columbia became the first jurisdiction to pass such a law. This spring, Virginia passed its own bill, which gives judges the option of requiring ISA if a driver exceeded 100 mph. Legislatures in Arizona, California, Georgia, Maryland, and New York are now considering their own proposals. (Proposals typically include a limited “override” feature allowing further acceleration during an emergency.)

“The bills are all a little bit different,” Cohen says. “But they are all taking the worst drivers and saying that this technology has to be put in their cars for the duration that a license is suspended.”

Politically, a focus on reckless drivers offers crucial advantages over a blanket ISA requirement like those that the EU has adopted and California has considered. Since only a small fraction of drivers are super-speeders (Cohen estimates the share at under 2% in New York state), the bills’ passage won’t affect most residents directly but can protect them from danger posed by others. The auto industry is also less likely to oppose such measures, since an ISA mandate for new vehicles presents a much greater threat to existing manufacturing and marketing practices.

The recent state proposals have shown bipartisan appeal: Virginia’s bill was signed into law by Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin, and bills have passed the state house and senate in GOP-dominated Georgia as well as Democrat-led Washington state. Cohen says that her basic pitch, revolving around safety and fairness, seems to resonate equally well on both sides of the aisle: “We’re not taking away your car; we’re just saying that you can’t drive recklessly,” she says of the current state bills. “You have to get to your destination safely, and not kill anyone along the way.”

If successful, the states’ legislation could serve as a gateway for broader ISA deployments, potentially including public fleets (as New York City has piloted). A single car with ISA can also prevent multiple drivers behind it from recklessly accelerating, so even a small number of ISA-equipped vehicles could have a dramatic impact on regional or even national road safety.

For now, Cohen’s primary goal is convincing more states to climb aboard the ISA bandwagon. Families for Safe Streets has helped coordinate the various campaigns by building a resource page, answering FAQs, and arranging for crash victims to give supportive testimony during hearings.

With the Trump administration showing hostility toward regulations of all kinds, a state-based approach toward traffic safety offers promise. “It’s inspiring to see how quickly some legislators can move,” Cohen says. “We’re pushing—and hoping that others follow suit.”

![[FREE EBOOKS] AI and Business Rule Engines for Excel Power Users, Machine Learning Hero & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Olekcii_Mach_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Apple Drops New Immersive Adventure Episode for Vision Pro: 'Hill Climb' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97133/97133/97133-640.jpg)

![Most iPhones Sold in the U.S. Will Be Made in India by 2026 [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97130/97130/97130-640.jpg)

![Apple to Shift Robotics Unit From AI Division to Hardware Engineering [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97128/97128/97128-640.jpg)