Testing Real-World Go Code: Table-Driven Tests, Subtests and Coverage

Introduction This post walks through testing a Go function that loads a .toml config file into a struct. We'll start by defining the data structure and the LoadConfig function that reads and decodes the file. but first,ensure you have go 1.24 installed, then create a go module using. go mod init playground one we have our go module, ensure the version of the go pinned on the go module is 1.24. create a go file called cfg.go with the following code: package config type ( Config struct { Api Apifutbol `toml:"api"` } Apifutbol struct { Apikey string `toml:"apikey"` Leagues []int `toml:"leagues"` Teams []int `toml:"teams"` Timezone string `toml:"timezone"` } ) The struct models the expected TOML configuration. Next, we’ll implement LoadConfig, which reads the file and decodes it into this struct. first, import the toml and the os packages in the same file: import ( "github.com/BurntSushi/toml" "os" ) download the package in the same directory using the terminal with the following command: go mod tidy then write the function: func LoadConfig(filename string) (*Config, error) { var cfg Config data, err := os.ReadFile(filename) if err != nil { return nil, err } if err = toml.Unmarshal(data, &cfg); err != nil { return nil, err } return &cfg, nil } The LoadConfig function takes a .toml file path, reads its contents, and unmarshal the data into the Config struct using github.com/BurntSushi/toml. It returns a pointer to the populated struct or an error. Testing To test our function, create a new file in the same package called cfg_test.go. echo "package api" > cfg_test.go then import the following packages: import ( "testing" "os" "path/filepath" "reflect" ) Since LoadConfig reads from the filesystem and parses external data, this qualifies more as an integration test than a pure unit test. Instead of using a real config file, we'll create a temporary one during the test. The testing package provides utilities like t.TempDir() that creates a temporary directory and automatically cleans it up afterward. To prepare for the test, we will: Create a temporary file inside the temp directory Define TOML data as a string Write the TOML data to the temporary file Now write the test function: func TestLoadConfig(t *testing.T) { tempfile := filepath.Join(t.TempDir(), "config.toml") data := ` [api] apikey = "12345" leagues = [11, 22, 33] teams = [11, 22, 33] timezone = "Europe/London" ` if err := os.WriteFile(tempfile, []byte(data), 0644); err != nil { t.Fatalf("cannot write to file: %v", err) } want := &Config{ Api: Apifutbol{ Apikey: "12345", Teams: []int{11, 22, 33}, Leagues: []int{11, 22, 33}, Timezone: "Europe/London", }, } got, err := LoadConfig(tempfile) if err != nil { t.Fatalf("Cannot load config: %v", err) } if !reflect.DeepEqual(*got, *want) { t.Fatalf("got %v want %v", got, want) } } Once the function is called, we check for an error and compare the result with our expected struct using reflect.DeepEqual You can now run the test using: go test It should pass. But let’s go further and check test coverage: go test -cover This shows the percentage of code covered by tests. You might see something like: coverage: 71.4% of statements This means some parts of the LoadConfig function aren’t being tested; most likely the error paths. To visualize what’s missing, generate a coverage report: go test -coverprofile=coverage.out go tool cover -html=coverage.out This opens a browser view showing exactly which lines aren’t covered. You’ll likely notice that the error branches haven’t been triggered yet. To fix that, we need to add test cases that cover those edge conditions, and that’s where subtests come in. Subtests Rather than writing multiple test functions for the same logic, Go encourages the use of subtests (introduced in Go 1.7). Subtests allow grouping related scenarios within a single test while isolating them for better logging and individual execution. subtests are written in this format : t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) { } it takes a string value as the name and the test package as a parameter to have access to the testing methods. Now let's refactor our initial tests by adding subtests to it func TestLoadConfig(t *testing.T) { t.Run("valid config", func(t *testing.T) { // we add the same code as before here }) } we can add other edge cases by defining additional subtest in the same test function. t.Run("No file", func(t *testing.T) { tempfile := filepath.Join(t.TempDir(), "config.toml") _, err := LoadConfig(tempfile) if err == nil {

Introduction

This post walks through testing a Go function that loads a .toml config file into a struct.

We'll start by defining the data structure and the LoadConfig function that reads and decodes the file.

but first,ensure you have go 1.24 installed, then create a go module using.

go mod init playground

one we have our go module, ensure the version of the go pinned on the go module is 1.24.

create a go file called cfg.go with the following code:

package config

type (

Config struct {

Api Apifutbol `toml:"api"`

}

Apifutbol struct {

Apikey string `toml:"apikey"`

Leagues []int `toml:"leagues"`

Teams []int `toml:"teams"`

Timezone string `toml:"timezone"`

}

)

The struct models the expected TOML configuration.

Next, we’ll implement LoadConfig, which reads the file and decodes it into this struct.

first, import the toml and the os packages in the same file:

import (

"github.com/BurntSushi/toml"

"os"

)

download the package in the same directory using the terminal with the following command:

go mod tidy

then write the function:

func LoadConfig(filename string) (*Config, error) {

var cfg Config

data, err := os.ReadFile(filename)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if err = toml.Unmarshal(data, &cfg); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &cfg, nil

}

The LoadConfig function takes a .toml file path,

reads its contents, and unmarshal the data into the Config struct using github.com/BurntSushi/toml.

It returns a pointer to the populated struct or an error.

Testing

To test our function, create a new file in the same package called cfg_test.go.

echo "package api" > cfg_test.go

then import the following packages:

import (

"testing"

"os"

"path/filepath"

"reflect"

)

Since LoadConfig reads from the filesystem and parses external data, this qualifies more as an integration test than a pure unit test.

Instead of using a real config file, we'll create a temporary one during the test.

The testing package provides utilities like t.TempDir() that creates a temporary directory

and automatically cleans it up afterward.

To prepare for the test, we will:

- Create a temporary file inside the temp directory

- Define TOML data as a string

- Write the TOML data to the temporary file

Now write the test function:

func TestLoadConfig(t *testing.T) {

tempfile := filepath.Join(t.TempDir(), "config.toml")

data := `

[api]

apikey = "12345"

leagues = [11, 22, 33]

teams = [11, 22, 33]

timezone = "Europe/London"

`

if err := os.WriteFile(tempfile, []byte(data), 0644); err != nil {

t.Fatalf("cannot write to file: %v", err)

}

want := &Config{

Api: Apifutbol{

Apikey: "12345",

Teams: []int{11, 22, 33},

Leagues: []int{11, 22, 33},

Timezone: "Europe/London",

},

}

got, err := LoadConfig(tempfile)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("Cannot load config: %v", err)

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(*got, *want) {

t.Fatalf("got %v want %v", got, want)

}

}

Once the function is called, we check for an error and compare the result with our expected struct using reflect.DeepEqual

You can now run the test using:

go test

It should pass. But let’s go further and check test coverage:

go test -cover

This shows the percentage of code covered by tests. You might see something like:

coverage: 71.4% of statements

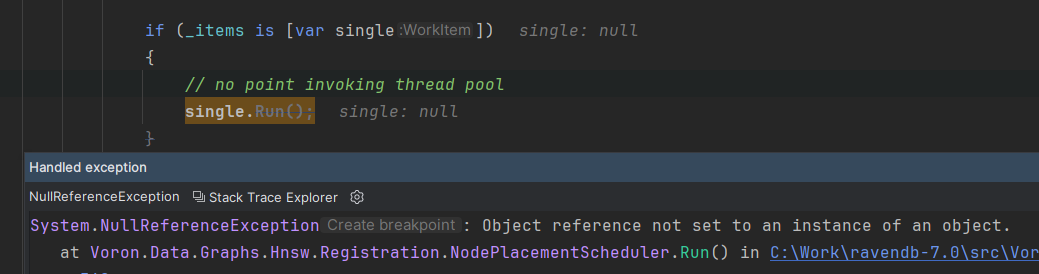

This means some parts of the LoadConfig function aren’t being tested; most likely the error paths. To visualize what’s missing, generate a coverage report:

go test -coverprofile=coverage.out

go tool cover -html=coverage.out

This opens a browser view showing exactly which lines aren’t covered. You’ll likely notice that the error branches haven’t been triggered yet. To fix that, we need to add test cases that cover those edge conditions, and that’s where subtests come in.

Subtests

Rather than writing multiple test functions for the same logic, Go encourages the use of subtests (introduced in Go 1.7). Subtests allow grouping related scenarios within a single test while isolating them for better logging and individual execution.

subtests are written in this format :

t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) { }

it takes a string value as the name and the test package as a parameter to have access to the testing methods.

Now let's refactor our initial tests by adding subtests to it

func TestLoadConfig(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("valid config", func(t *testing.T) {

// we add the same code as before here

})

}

we can add other edge cases by defining additional subtest in the same test function.

t.Run("No file", func(t *testing.T) {

tempfile := filepath.Join(t.TempDir(), "config.toml")

_, err := LoadConfig(tempfile)

if err == nil {

t.Fatal("expected error for missing file, but got nil")

}

})

Now let's add one more edge case for bad toml data:

t.Run("invalid toml", func(t *testing.T) {

tempfile := filepath.Join(t.TempDir(), "config.toml")

data := "invalid config"

err := os.WriteFile(tempfile, []byte(data), 0644)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("failed to write invalid toml file: %v", err)

}

_, err = LoadConfig(tempfile)

if err == nil {

t.Fatal("expected error for invalid toml, but got nil")

}

})

Run with the -cover flag.

You should now see full coverage. Add more cases if needed. The current test works, but it’s not DRY. Adding more edge cases like this gets repetitive.

Let’s fix that next.

Table Driven Test

Table-driven tests make tests concise, scalable, and easy to extend. Instead of writing a subtest for each case, we define a slice or map of test cases and loop through them.

let's refactor our code using a table-driven style. first, we refactor our test variables into a single var block outside the test function:

var (

validConfig = `` // populate values for all from previous code

invalidConfig = ""

want = &Config{}

)

Next, we declare and immediately populate a map[string]struct{} inside our test function. Each key is the test case name, and the value is an anonymous struct that holds the input, expected output, and whether we expect an error:

func TestLoadConfig(t *testing.T) {

tests := map[string]struct {

data string

want *Config

expectError bool

}{

"valid config": {data: validConfig, want: want, expectError: false},

"No file": {data: "", want: want, expectError: true},

"Invalid toml": {data: invalidConfig, want: want, expectError: true},

}

// next code beneath goes here

}

We then loop through each test case using t.Run.

For each case, we create a temporary file,

write the config data (if any), run LoadConfig, and assert based on the expectation:

for name, tc := range tests {

t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) {

tempfile := filepath.Join(t.TempDir(), "config.toml")

if tc.data != "" {

if err := os.WriteFile(tempfile, []byte(tc.data), 0644); err != nil {

t.Fatalf("cannot write to file: %v", err)

}

}

got, err := LoadConfig(tempfile)

if tc.expectError {

if err == nil {

t.Fatalf("expected an error but got nil")

}

} else {

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("did not expect error, got: %v", err)

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(*got, *tc.want) {

t.Fatalf("got %v want %v", got, tc.want)

}

}

})

}

Our tests now look much cleaner than before.

We’ve eliminated multiple t.Run blocks and moved everything into a single loop.

However, we still have too many if statements, which hurts readability.

We can improve this further using the assert and require helpers from the testify package.To do this, import:

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/require"

Then, initialize them just before the tests struct inside the test function:

assert := assert.New(t)

require := require.New(t)

now let's swap out the if statements using our new helper methods

if tc.data != "" {

if err := os.WriteFile(tempfile, []byte(tc.data), 0644); err != nil {

require.Nil(err)

}

}

got, err := LoadConfig(tempfile)

if tc.expectError {

require.NotNil(err)

} else {

require.Nil(err)

assert.Equal(*got, *tc.want)

}

The test should still run as normal, and coverage should remain 100%. You can run go test -cover to verify.

Summary

Our tests are now cleaner, easier to read, and more scalable.

Together, we’ve covered:

- How to write integration-style config file tests in Go

- How to handle edge cases using subtests

- How to structure and simplify tests with a table-driven style

- How to improve test readability using

testify

— Tobiloba Ogundiyan

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![Google reveals NotebookLM app for Android & iPhone, coming at I/O 2025 [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/05/NotebookLM-Android-iPhone-6-cover.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Reports Q2 FY25 Earnings: $95.4 Billion in Revenue, $24.8 Billion in Net Income [Chart]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97188/97188/97188-640.jpg)