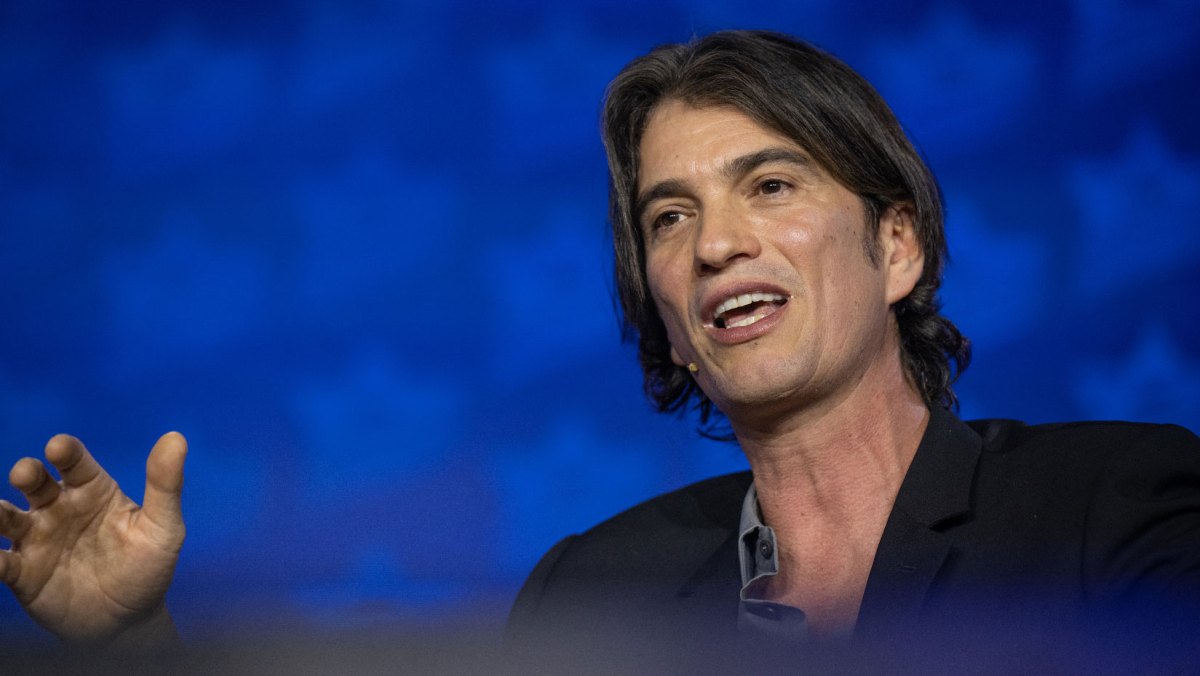

'Never had a chance to defend myself’: Medikabazaar's Vivek Tiwari speaks out on governance and whistleblower allegations

Eight months after his abrupt ouster from Medikabazaar, co-founder Vivek Tiwari calls it a “corporate coup” in his first detailed interview, opening up on audit lapses, boardroom politics, and his fight to reclaim control.

“This feels like a corporate coup.”

That’s how Vivek Tiwari describes his dramatic fall from the top at Medikabazaar, the healthtech startup he co-founded and steered through the chaotic highs of the COVID-19 boom. Once the face of a fast-scaling B2B platform backed by marquee investors, Tiwari was abruptly terminated “for cause” in August 2023—an ouster he claims was politically motivated, opaque, and deeply unfair.

Medikabazaar has since been engulfed in controversy. A whistleblower complaint triggered a forensic audit, allegedly revealing red flags—phantom inventory, fictitious transactions, and potential related-party dealings. PwC, the company’s auditor, resigned. Investors launched an internal cleanup.

Till now, the founder at the centre of the storm had been silent. Not anymore.

In an exclusive interview with YourStory, Vivek Tiwari offers his first detailed account since his removal as the CEO. He opens up about the audit, whistleblower allegations, and the subsequent internal power struggles. He says he was kept in the dark, cut out of critical decisions, and ultimately made the scapegoat—while others named in the same complaints remained untouched.

Tiwari insists he always aimed to build systems with transparency. He speaks of the early years, and how witnessing his grandmother's struggle with access to care in a Tier II town instilled a resolve to find a solution. The business, he says, was rooted in impact and inclusion—not just profit. But the company’s breakneck growth during the COVID-19 pandemic, internal delays in hiring key CXOs, and the complex dynamics of boardroom control left him exposed.

“No founder ever wants to build a business without prudent oversight,” he says. “I tried to bring in the right people, hired a Big Four auditor, pushed for systems. But collective delays and the pace of growth left gaps.”

The audit, he claims, turned adversarial only after a whistleblower complaint. Until then, he believed PwC’s engagement was routine. Tiwari asserts that the findings of the forensic audit were never flagged to him during the audit. Nor, he adds, did the board or finance team raise alarms before the investigation.

He says his removal came a day after he revoked a consent letter signed under duress—one that allowed his shareholding to be diluted if wrongdoing was found but sought to preserve his board seat. The next day, the board voted to terminate him “for cause” in a 50-minute meeting.

In an unfiltered conversation about ambition, breakdowns in oversight, and a legal battle to clear his name Vivek Tiwari lays out his side of the story—of growth, governance, and the internal rupture.

Edited excerpts:

YourStory [YS]: As a founder, how did you approach governance and systems in Medikabazaar?

Vivek Tiwari [VT]: I’ve always believed in governance and wanted to build systems and controls into the business from the start. No founder ever wants to build a business without prudent oversight.

During COVID-19, however, we faced tremendous challenges. The volume of orders surged, and we had to upgrade our systems and processes, while simultaneously trying to keep up with demand. We also needed a stronger management team in place to handle the complexity that came with that scale. Some delays in putting the right people in place stemmed from collective decision-making processes. For example, if it were just up to me, I would have hired a CFO or CXO back in 2020. But those decisions often involved others, and that slowed things down.

The rapid five- to ten-fold growth exposed the business to systemic risks, and we weren’t ready with the internal controls needed to manage that scale. That’s partly why I brought in PwC as an auditor. I wanted transparency, control, ethics, and governance. Up until the whistleblower letter surfaced, PwC hadn’t escalated any major findings to me.

YS: You were the CEO. Why weren’t you aware of red flags like phantom inventory or fictitious transactions mentioned in the forensic audit?

VT: I was managing many roles—CEO, founder, investor relations, board member, audit and governance committees. Much of the financial oversight was managed by my co-founder and professional CFOs. By June 2023, I had onboarded a CFO I believed could shoulder the financial responsibilities. Normally, a CFO reports to the board and audit committee, so I expected they would surface any red flags. I trusted the team around me and believed that if there were serious issues, they would bring them up.

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. I came to know about the red flags only after the whistleblower letter triggered the forensic audit. Even then, PwC didn’t immediately share their findings with me. Until December 2023, PwC hadn’t flagged anything to me.

YS: So, the finance team was empowered, but nothing was flagged to you internally?

VT: Correct. The finance and internal audit teams had the authority to raise concerns. But the phantom inventory, fictitious transactions—none of it was ever reported to me directly. I only learned of these through the later phases of the audit or investigation.

I wasn’t involved in the day-to-day revenue reporting either. That responsibility fell under our Chief Revenue Officer, Jitesh Mathur. He was a CXO and was responsible for overseeing those numbers. I had a team of CXOs, and while I don’t want to question their capabilities, the process should have allowed for impartial investigations. That never happened.

YS: Did Jitesh Mathur receive the same scrutiny as you and your co-founder?

VT: I feel like this was a corporate coup. It wasn’t transparent or fair. The founders were sidelined early, even though we built the foundation of this business. The company still has substantial revenue today. So who built that? Me and my team. Yet, only me and my co-founder were targeted, while many others named in the whistleblower letter are still working in the company. It wasn’t just about me and Ketan [Malkan]—18 people were named. If fairness was truly the goal, the entire management team should have been scrutinised.

YS: In August, investors terminated you "for cause." You’re contesting that in court. On what grounds?

VT: I wasn’t treated justly. I raised hard questions—why wasn’t I given access to reports, why was I being scapegoated? I even signed a consent letter allowing my stake to be diluted if any wrongdoing was found—as long as I remained a director. I wanted to support a fair investigation. But when I revoked that consent, I was removed the very next day. It was abrupt and without due process. I had no option but to seek legal redress in the Delhi High Court.

YS: Do you think the board acted prematurely? Or were they under investor pressure?

VT: I can’t comment on their intentions. I just know I felt cornered in my own company. Even as I tried to access reports and understand what was happening, I was blocked. It felt premeditated. I can’t speak to what investors or board members were really thinking, but I was left without access and clarity.

YS: Was there any internal discussion before the audit that flagged discrepancies?

VT: No, not that I was aware of. We had a CFO, a finance team, and a board. CXOs interacted with the board, not just me. Formal meetings were held, and everyone had their role. If the board had concerns, they never expressed them openly before the audit. Until the whistleblower complaint surfaced, there were no blatant red flags discussed with me.

YS: What are your thoughts on the whistleblower claims? Are they factual or exaggerated?

VT: Most claims were about finances and revenues. None accused me of personal involvement. They seemed based on misrepresented or misunderstood information. Everyone named should have been given a fair chance to respond, but that didn’t happen. The investigation process lacked fairness and clarity. I don’t even know if the third-party reports fairly represented the company’s operations.

YS: Do you have investor support now? Do they believe you were wrongfully terminated?

VT: Not all investors are on the board. I’ve had conversations with several over the past year. Many may not fully know what transpired. The board today represents only a few investors. Others, who aren’t on the board, might view things differently once they understand the full picture. I have faith that when they hear the facts, many will support me.

YS: Considering how things panned out, do you think the governance frameworks at the company were robust enough to prevent such conflicts and side deals?

VT: As I said, Medikabazaar was a high-growth business post-COVID-19. When we talk about governance, it's about having the right processes and systems in place to meet compliance and regulatory needs. It depends on the kind of team you have, the systems you build, your clarity as a founder, and the pressure from the board and shareholders to implement governance.

With my intent, I tried my best—hired a Big Four auditor, tried to hire a CFO, and wanted to grow with strong fundamentals. However, due to the nature of our business, which was very operational, and due to collective decision-making, there were execution gaps and delays. Reporting gaps and red flags were not brought to my knowledge in time. When they were identified, I was not involved in the process. It feels like I’m being victimised while others named have been let off.

YS: How do you view the company’s decision to terminate your employment “for cause”? Are you contesting it on procedural grounds or merit?

VT: I’m contesting it on both. My employment agreement had specific terms, including the need for fair opportunity to respond in case of any wrongdoing. There needed to be a finding, a breach of trust, or misconduct, and a fair chance to present my case. That didn’t happen. I was terminated after a 50-minute board meeting, just a day after I revoked certain consents I gave under duress to help the company during the investigation. I wasn’t weak—I just wanted to help. But I was pushed out unfairly.

YS: You said you signed consent documents under duress. But weren't shareholder agreements post-2021 considered founder-friendly?

VT: I’m not talking about the shareholder agreements themselves—those were signed with legal guidance. I’m referring to certain consents I gave during the investigation process. There was no direct allegation against me at the time, but I felt if I didn’t step back and cooperate, the process would lose its credibility. I gave those consents in good faith, but I wasn’t told what my wrongdoing was. Later, I had to revoke them—and then came the termination.

YS: What do you make of the indemnity claim by investors including Creages, the CDC Group, HealthQuad, and Ackermans & van Haaren?

VT: I can't comment in detail since this is subjudice. These claims will be addressed in court. Whether they have merit or not is not for me to decide at this time.

YS: There’s also a whistleblower allegation regarding a parallel business. Were you aware of this?

VT: No, I wasn’t. Jitesh Mathur was the chief revenue officer. He interacted with me and the board but never brought up anything of this sort. If these things were happening, they should be properly investigated by the board and company. But during my time, nothing like this was shared with me.

YS: How closely were you involved in reviewing deals under Jitesh Mathur’s leadership?

VT: Jitesh Mathur had the authority as a CXO to execute deals. He didn’t need my approval for most things. If a deal had financial implications, it would go to the CFO. We had a strong leadership team, and they were empowered. I wasn’t involved in every deal.

YS: Employees have claimed some objections were raised internally about these deals. Were they escalated to you?

VT: Not that I’m aware of. We had a CHRO, and there were grievance redressal processes in place. If something reached me, I dealt with it. If it didn’t, I can’t speak about it. We had committees like the Nomination and Remuneration Committee, and others. If something was missed, it didn’t come to me.

YS: It’s alleged United Imaging poached Medikabazaar talent and the company lacked a non-poaching agreement. What’s your take on the partnership?

VT: Medikabazaar launched United Imaging in India. We had a strong partnership. If employees moved between companies, it was likely due to business decisions and not rivalry. To my knowledge, there wasn’t a formal poaching issue. These concerns should be addressed by the current board and management.

YS: Final question—if given a second chance, what would you do differently?

VT: I would still rebuild Medikabazaar. This platform has huge potential to transform healthcare in India. It was never just about making profits. It’s about impact—making medical care more accessible in the most populous country in the world. I believe we need platforms like this. If I could do it again, I’d build it with stronger systems, deeper insight, and better controls. That’s the message I’d like to leave behind as a founder.

Edited by Kanishk Singh

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

.jpg?#)

![Apple to Shift Robotics Unit From AI Division to Hardware Engineering [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97128/97128/97128-640.jpg)

![Apple Shares New Ad for iPhone 16: 'Trust Issues' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97125/97125/97125-640.jpg)