Meet the Space Resistance Companies

If you’re at all unsettled by the amount of power that Elon Musk wields on Earth, don’t look up. There are now essentially three big players controlling what goes into space and who gets access to increasingly valuable space-based communications and surveillance services: Russia, China, and Elon Musk.In 2024, Musk’s rocket company SpaceX accounted for more than half of all orbital launch attempts globally—more than all countries outside the U.S. combined—with 134 successful launches of its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. His Starlink constellation of more than 7,000 satellites provides high-speed internet connectivity to more than 4.6 million customers worldwide, including residential users, businesses, federal agencies, and foreign governments. A classified Starlink offshoot, called Starshield, has a contract to provide the U.S. government not only with military-grade communications but space-surveillance capabilities, too.The turbulent global politics of the past few years—from the Russian invasion of Ukraine to the reelection of Donald Trump—have shown the risks of overreliance on any one country (or person) for access to space resources. And in the wake of the administration’s breakup with NATO allies, Europe and Canada are accelerating their efforts to achieve space independence, boosted by new investment and cross-border cooperation.“Europe has always had a preference to buy local, but [it] didn’t always happen,” says Justus Kilian, partner at New York City-based venture firm Space Capital. “Now that there’s an urgency and necessity to develop domestic capabilities, local companies will get strong preference.” (Though his firm focuses on North American startups, he says U.S.-based companies can set up shop in Europe to take advantage of the boom.) Jussi Sainiemi, partner at Helsinki-based Voima Ventures, an early-stage deeptech fund that’s invested in hyperspectral satellite startup Kuva Space, says that European interest in “dual-use” technology—with civilian and military applications—has grown since the start of the war in Ukraine. Now it’s peaking. “Since the Trump administration has indicated decreasing support to Ukraine and Europe,” he says, “the rise of defense-related investment programs has dominated European news flow.”In the next year, governments and companies in Europe and elsewhere will take major steps toward space sovereignty by launching new rockets and rapidly building out satellite constellations in low-Earth orbit. Here’s how some of the best-positioned players are chipping away at Musk’s near monopolies in launch services, communications, and earth monitoring. SpaceX Launch CompetitorsOn March 30, a 92-foot-tall, two-stage Spectrum rocket made by German company Isar Aerospace crashed into the sea off the Norwegian Island of Andoya in spectacular fashion about 40 seconds after taking off. It was the first vertical orbital rocket launch ever attempted from Western Europe. (French company Arianespace launched its missions on behalf of the European Space Agency from French Guiana.) In 2025, there could be several more launch attempts. All will be small-lift rockets designed to get small satellites into low-earth orbit—avoiding the hassle of shipping across the Atlantic to get up in space.Daniel Metzler, Isar’s chief executive and cofounder, called the recent attempt “a great success”—with a clean liftoff, 30 seconds of flight, and successful deployment of the rocket’s Flight Termination System, which safely scraps the flight in case of system failures. The Norwegian space agency has already tapped Isar to launch two Arctic Ocean spy satellites before 2028, assuming it can get its rockets up without exploding.Later this year, the action will move to SaxaVord Spaceport in Shetland, Scotland. There, the Scottish startup Orbex Space plans to attempt the first vertical rocket launch into orbit from UK soil. Its U.K.-manufactured rocket, called Orbex Prime, is a two-stage vehicle designed to be reusable, and powered by a renewable bio-fuel that produces 96% lower CO2 emissions than fossil-fuel systems. [Photo: courtesy of RFA]German startup Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA) also aims for a 2025 commercial launch of its multistage vehicle from SaxaVord. (These northern launch sites are good for getting imaging satellites into “sun-synchronous” polar orbits that put them in continuous daylight, which is better for imaging.) Another German company, HyImpulse, hopes to launch its multistage SL1 orbital rocket this year; no launch site has been announced. Isar, Orbex, RFA, and HyImpulse were joint recipients of $48 million in funding from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Boost program in 2024; the German government committed an additional €95 million to Isar, RFA, and HyImpulse.Meanwhile, Rocket Lab, which was founded in New Zealand but is headquartered in Long Beach, CA, continues to offer the most reliable small-lift alternative to SpaceX. The company’s Electron rockets have already launche

If you’re at all unsettled by the amount of power that Elon Musk wields on Earth, don’t look up. There are now essentially three big players controlling what goes into space and who gets access to increasingly valuable space-based communications and surveillance services: Russia, China, and Elon Musk.

In 2024, Musk’s rocket company SpaceX accounted for more than half of all orbital launch attempts globally—more than all countries outside the U.S. combined—with 134 successful launches of its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. His Starlink constellation of more than 7,000 satellites provides high-speed internet connectivity to more than 4.6 million customers worldwide, including residential users, businesses, federal agencies, and foreign governments. A classified Starlink offshoot, called Starshield, has a contract to provide the U.S. government not only with military-grade communications but space-surveillance capabilities, too.

The turbulent global politics of the past few years—from the Russian invasion of Ukraine to the reelection of Donald Trump—have shown the risks of overreliance on any one country (or person) for access to space resources. And in the wake of the administration’s breakup with NATO allies, Europe and Canada are accelerating their efforts to achieve space independence, boosted by new investment and cross-border cooperation.

“Europe has always had a preference to buy local, but [it] didn’t always happen,” says Justus Kilian, partner at New York City-based venture firm Space Capital. “Now that there’s an urgency and necessity to develop domestic capabilities, local companies will get strong preference.” (Though his firm focuses on North American startups, he says U.S.-based companies can set up shop in Europe to take advantage of the boom.) Jussi Sainiemi, partner at Helsinki-based Voima Ventures, an early-stage deeptech fund that’s invested in hyperspectral satellite startup Kuva Space, says that European interest in “dual-use” technology—with civilian and military applications—has grown since the start of the war in Ukraine. Now it’s peaking. “Since the Trump administration has indicated decreasing support to Ukraine and Europe,” he says, “the rise of defense-related investment programs has dominated European news flow.”

In the next year, governments and companies in Europe and elsewhere will take major steps toward space sovereignty by launching new rockets and rapidly building out satellite constellations in low-Earth orbit. Here’s how some of the best-positioned players are chipping away at Musk’s near monopolies in launch services, communications, and earth monitoring.

SpaceX Launch Competitors

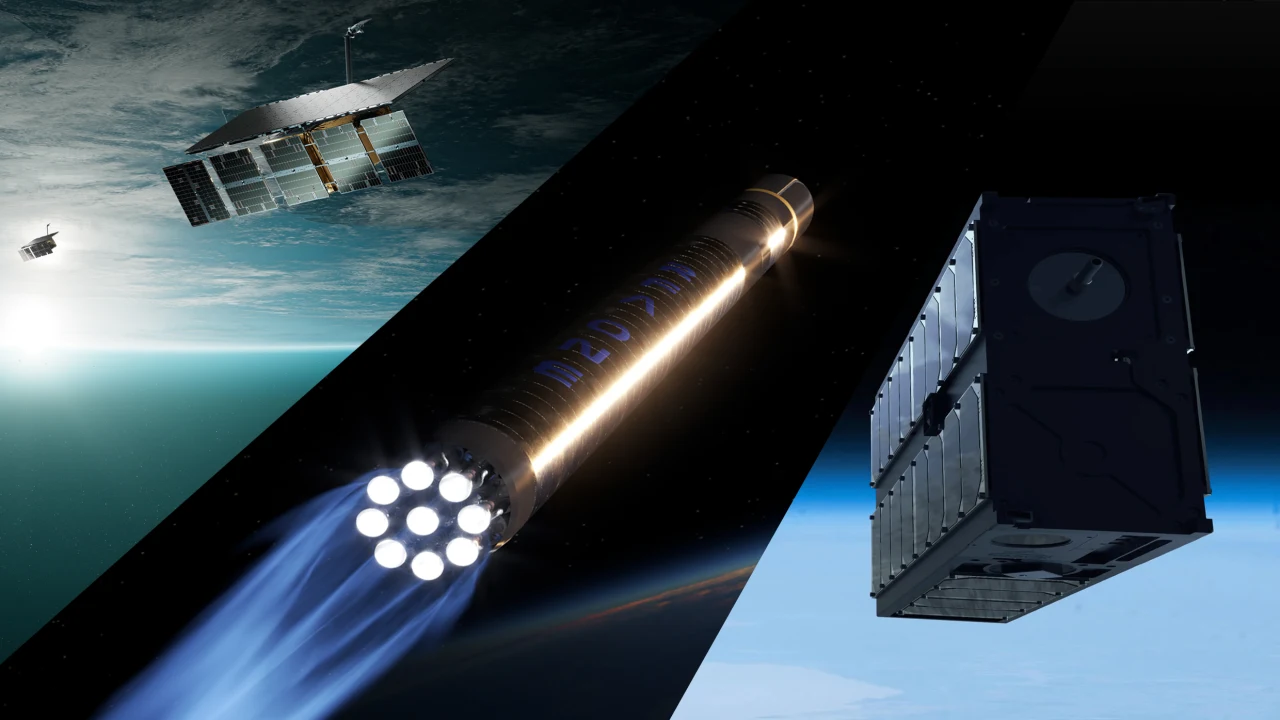

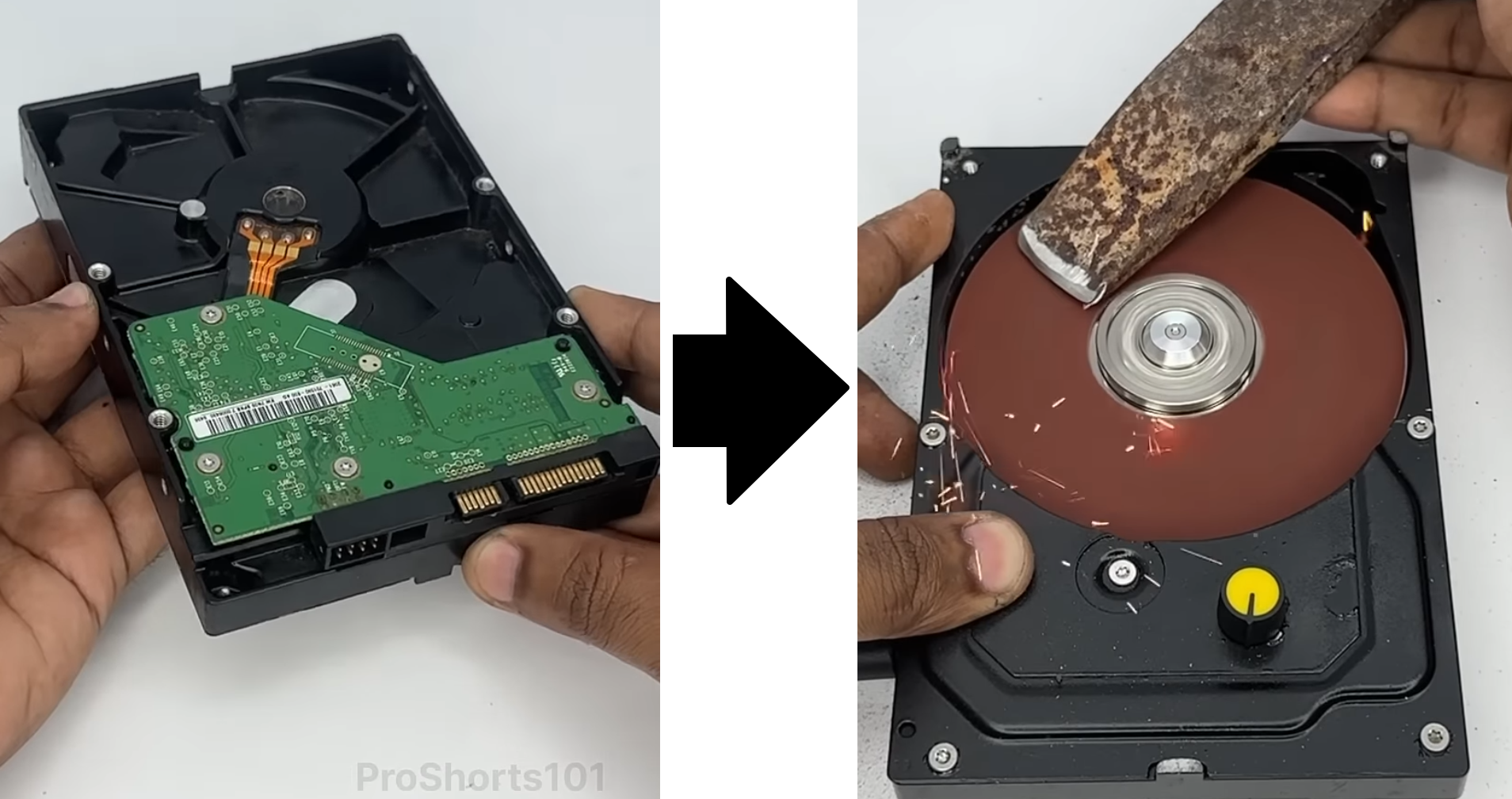

On March 30, a 92-foot-tall, two-stage Spectrum rocket made by German company Isar Aerospace crashed into the sea off the Norwegian Island of Andoya in spectacular fashion about 40 seconds after taking off. It was the first vertical orbital rocket launch ever attempted from Western Europe. (French company Arianespace launched its missions on behalf of the European Space Agency from French Guiana.) In 2025, there could be several more launch attempts. All will be small-lift rockets designed to get small satellites into low-earth orbit—avoiding the hassle of shipping across the Atlantic to get up in space.

Daniel Metzler, Isar’s chief executive and cofounder, called the recent attempt “a great success”—with a clean liftoff, 30 seconds of flight, and successful deployment of the rocket’s Flight Termination System, which safely scraps the flight in case of system failures. The Norwegian space agency has already tapped Isar to launch two Arctic Ocean spy satellites before 2028, assuming it can get its rockets up without exploding.

Later this year, the action will move to SaxaVord Spaceport in Shetland, Scotland. There, the Scottish startup Orbex Space plans to attempt the first vertical rocket launch into orbit from UK soil. Its U.K.-manufactured rocket, called Orbex Prime, is a two-stage vehicle designed to be reusable, and powered by a renewable bio-fuel that produces 96% lower CO2 emissions than fossil-fuel systems.

German startup Rocket Factory Augsburg (RFA) also aims for a 2025 commercial launch of its multistage vehicle from SaxaVord. (These northern launch sites are good for getting imaging satellites into “sun-synchronous” polar orbits that put them in continuous daylight, which is better for imaging.) Another German company, HyImpulse, hopes to launch its multistage SL1 orbital rocket this year; no launch site has been announced. Isar, Orbex, RFA, and HyImpulse were joint recipients of $48 million in funding from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Boost program in 2024; the German government committed an additional €95 million to Isar, RFA, and HyImpulse.

Meanwhile, Rocket Lab, which was founded in New Zealand but is headquartered in Long Beach, CA, continues to offer the most reliable small-lift alternative to SpaceX. The company’s Electron rockets have already launched five commercial payloads in 2025, after 15 successful launches in 2024, most from Rocket Labs’s Complex 1 launch site on New Zealand’s North Island. It plans to test-launch its larger, medium-lift Neutron rocket later this year.

For larger payloads, European and other international customers can look to future launches of the Ariane 6 heavy-launch rocket, operated by Arianespace and developed in partnership with the ESA and the French national space agency. The Ariene 6 made its second commercial flight this March, lifting off from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana. Five more launches are planned in 2025.

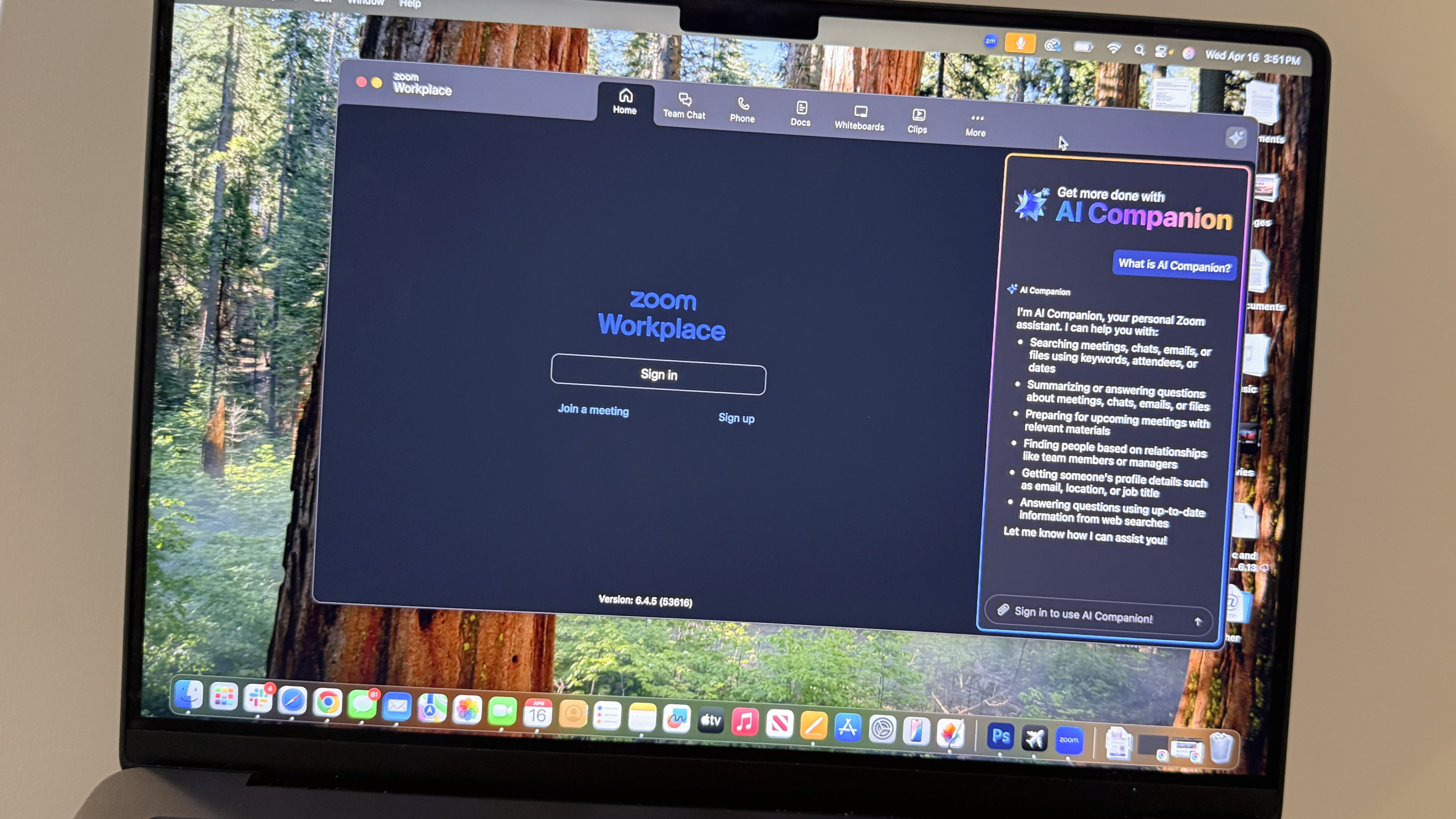

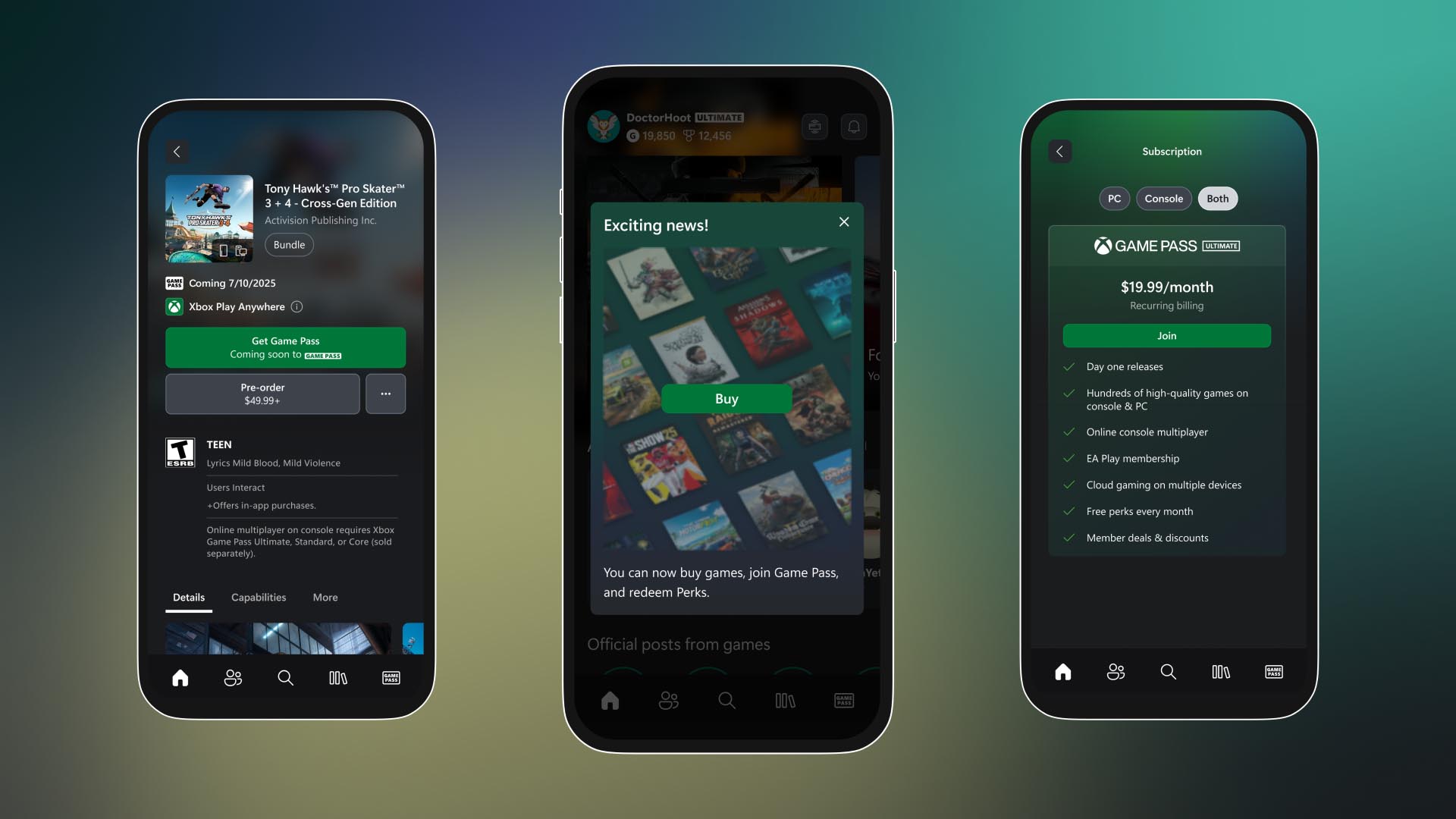

Satellite communications alternatives

It will take time for any competitor to catch up with Starlink’s advantage in low-earth-orbit (LEO) broadband satellites. But Europe and Canada are ratcheting up their efforts with some major investments.

Funded by the EU, the ESA, and private backers, IRIS2 is an $11.1 billion project to build a constellation of some 290 satellites in low- and medium-earth orbits. The constellation, expected to be operational by 2030, will provide secure and resilient connectivity for government applications and commercial services. IRIS2 is being developed and deployed by three European satellite network operators: Luxembourg-based SES, Madrid-based Hispasat, and Eutelsat. The Paris-based Eutelsat’s OneWeb subsidiary also happens to be Starlink’s biggest competitor in government and commercial markets, with a LEO constellation of nearly 700 satellites. OneWeb’s constellation is already being used by Ukraine’s armed forces as a supplement—and potential replacement—for Starlink service.

In Canada, the Ottawa-based Telesat is aggressively building out its Lightspeed Network, a planned constellation of 198 LEO satellites that will provide high-speed broadband to underserved communities in Canada and beyond, and help governments modernize their satellite communications technology and bolster NATO defense capabilities. Telesat has contracted 14 launches starting in mid-2026 to deploy all of these satellites within a year. The launch provider will be SpaceX.

New approaches to monitoring and surveillance

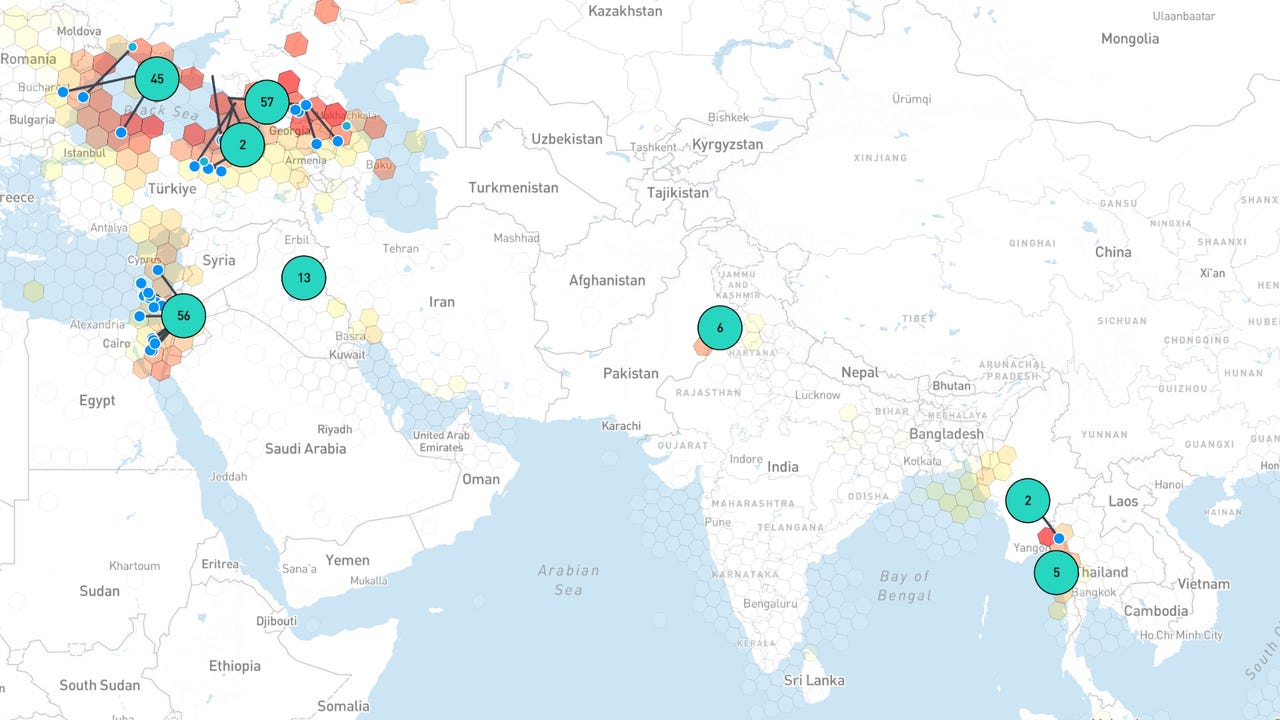

In early March, the Trump administration abruptly cut off Ukraine’s access to the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency’s (NGA) commercial satellite imagery platform, which had provided the country with images aggregated from commercial providers. (The platform is managed by U.S. aerospace firm Maxar Technologies, which confirmed that it blocked Ukrainian users’ access.) Access was restored 11 days later, but the episode underscored the need for countries to diversify their sources of satellite intel. Several key players have emerged/are emerging to cater to the interests of anxious democracies in Europe and elsewhere.

Founded in 2010, San Francisco-based Planet Labs sells satellite imagery from its constellation of cubesats to customers in industry and government. In the first few months of 2025, the company announced a multiyear contract worth an undisclosed amount with ESA and a $230 million contract with another, unspecified customer in the Asia-Pacific region. Planet operates more than 200 satellites that can image the entire Earth daily, using high-resolution electro-optical sensors, which detect light in the visible spectrum. It launched its first next-gen Pelican-2 satellite, featuring Nvidia’s Jetson edge AI platform, on a SpaceX rocket this January, part of a planned constellation of 32 such satellites.

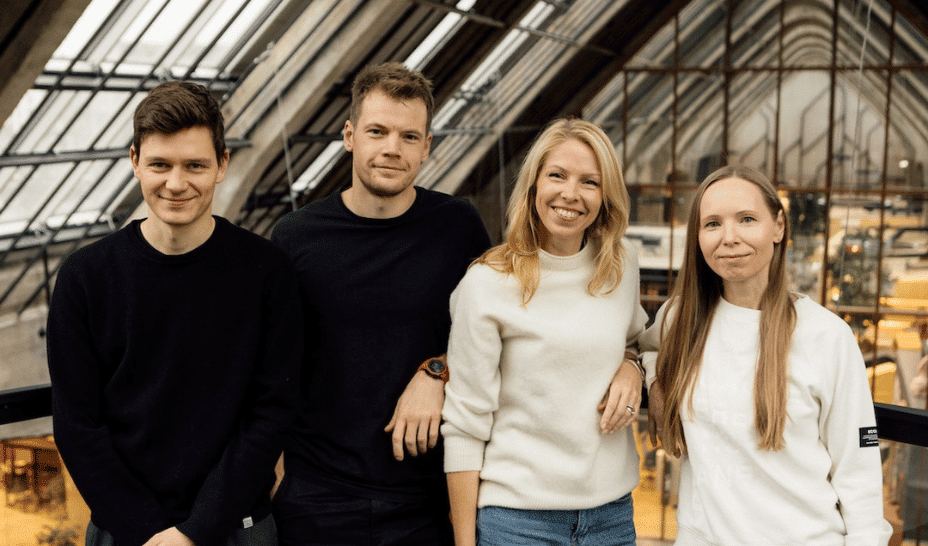

Interest in imagery from Finnish-Polish satellite maker and operator Iceye is also surging. The company’s constellation of microsatellites is equipped with synthetic aperture radar (SAR), which can “see” through clouds and darkness. Iceye has launched nearly 50 of its satellites into orbit since 2018, including nine in 2024, and plans to launch more than 20 per year in 2025 and subsequent years. Its customers include Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense, the Greek Space Agency, and the Polish Armament Group, as well as the U.S. Department of Defense.

Another Finnish company, Kuva Space, launched its rectangular Hyperfield-1 hyperspectral nanosatellite last July, the first in a planned constellation of 100. Its hyperspectral camera and onboard AI allow it to distinguish Earth materials and conditions based on distinct spectral signatures, and to detect threats and anomalies for defense applications, such as creating an alert if a ship or vessel does not transmit an Automatic Identification System signal. With a second launch this year, the company aims to provide daily observation by 2027 and even more frequent monitoring by 2030. In January 2025, Czech startup TRL Space successfully launched its own hyperspectral TROLL satellite, and is supervising work on a second Czech-made satellite designed specifically for the Ukrainian Armed Forces in cooperation with Ukrainian specialists.

Finally, SkyWatch, based in Waterloo, Ontario, is a go-to source for earth observation data for business and government customers around the globe. It pulls together imagery from the world’s leading providers in one pay-as-you-use application, enabling European and other government customers to use sophisticated “tip and cue” services that stitch together data coming from multiple sensor platforms to track areas of interest without contracts or major capital investments.

The importance of funding

Space infrastructure is hard to build and has traditionally required a level of investment well beyond anything that’s been seen before in Europe. Funding is notching up—in 2024, Europe accounted for four of the 15 largest private space funding deals globally. And last month, the European Commission introduced ReArm Europe, a $876 billion investment to strengthen Europe’s sovereign defense capabilities, including in space.

Historically, Europe has invested much less in space than the U.S., devoting just 3% of total defense budget to space, versus 9% in the U.S. The European Space Agency’s 2025 budget of around $8.4 billion is roughly a third of NASA’s $25 billion budget request for 2025, which is not yet approved. Support from the U.S. government was key to establishing Musk’s space dominance: In 2006, SpaceX secured $278 million in NASA seed money to help fund the development and flight demonstration of the Falcon 9’s Dragon capsule; in 2008, the company received a $1.6 billion contract with the agency to fly resupply missions to the ISS.

“I hope Europe is successful,” says Kilian, of Space Capital. “It’s important that they are. But Europe is more than 10 years behind us.” He notes that since fewer companies get funding in Europe, there’s less competition driving results. Even so, he says, “new companies serving sovereign needs will emerge and become decent investments. But it will take these companies more time and more money to achieve similar outcomes.”

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![GrandChase tier list of the best characters available [April 2025]](https://media.pocketgamer.com/artwork/na-33057-1637756796/grandchase-ios-android-3rd-anniversary.jpg?#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![Apple M4 13-inch iPad Pro On Sale for $200 Off [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97056/97056/97056-640.jpg)

![Apple Shares New 'Mac Does That' Ads for MacBook Pro [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97055/97055/97055-640.jpg)