Shallow vs Deep Copies in Python, What You Think You Know (but Might Not)

Copying objects in Python may seem like a simple task. You’ve got a list, or maybe a dictionary, and you want a copy of it. Easy, right? Just assign it to a new variable or maybe use copy(). But under the hood, things can get tricky, especially when your data is nested or mutable. That's where the concepts of shallow and deep copies come in. In this post, we’ll break down what these terms really mean, why choosing the right one matters, and show real-world examples of how copying can either save or sabotage your program. Why copying objects deserves more attention than you think Python doesn’t always behave the way newcomers expect when it comes to copying data structures. When you assign one variable to another, you’re not copying the object, you’re just copying the reference. That means both variables point to the same object in memory. the_original = [1, 2, 3] the_copy = the_original the_copy[0] = 999 print(the_original) # [999, 2, 3] print(the_copy) # [999, 2, 3] Yep. Changing the_copy also changed the_original. That’s because they’re actually the same list. To really clone an object, Python offers two approaches: Shallow copy: Copies the outer object, but not the nested objects. Deep copy: Recursively copies everything inside, making a true clone. Why you need to know your copying options When working with complex data (think lists of dictionaries, or class instances that reference each other), copying incorrectly can lead to bugs that are super hard to trace. Imagine writing a function that modifies a list passed as an argument, expecting to work with a separate copy, but accidentally changing the original data instead. Copying looks simple, but choosing the wrong method can introduce silent data corruption, hard-to-reproduce bugs, or unnecessary memory usage. So, let’s break it all down: What is a shallow copy? A shallow copy creates a new object, but instead of copying nested objects inside, it just copies the references to them. You can create a shallow copy with: The copy() method (for lists and dicts) The copy.copy() function from the copy module Let’s look at a simple example: import copy the_original = [[1, 2], [3, 4]] the_shallow = copy.copy(the_original) the_shallow[0][0] = 999 print(the_original) # [[999, 2], [3, 4]] print(the_shallow) # [[999, 2], [3, 4]] Only the outer list was copied. The inner lists still point to the same memory. What is a deep copy? A deep copy, created with copy.deepcopy(), duplicates everything not just the container, but all nested elements too. This gives you an entirely separate object tree that you can modify without fear of affecting the original. import copy the_original = [[1, 2], [3, 4]] the_deep = copy.deepcopy(the_original) the_deep[0][0] = 999 print(the_original) # [[1, 2], [3, 4]] print(the_deep) # [[999, 2], [3, 4]] Now we’re talking! The original stays safe. Case Study 1: When shallow copy i*s* the right choice Let’s say you’re building a GUI-based app where each user gets a personalized page layout. Each layout includes a header, a sidebar, and a settings section. The header and sidebar are exactly the same across all users they contain static elements like logos and navigation menus. Only the settings section varies per user like theme and language preferences. In this case, you want to share most of the structure between users to save memory and initialization time. You just need a different settings object per user. So… enter shallow copy. import copy # Shared UI components (assumed large and immutable) header = {"logo": "MyApp", "menu": ["Home", "Profile", "Logout"]} sidebar = {"links": ["Dashboard", "Settings", "Billing"]} # Base layout template layout_template = { "header": header, "sidebar": sidebar, "settings": {"theme": "light", "language": "en"} } # Create a user-specific layout using shallow copy user_layout = copy.copy(layout_template) # Customize just the settings for this user user_layout["settings"]["theme"] = "dark" print("User Layout:") print(user_layout) print("\nTemplate Layout (unchanged):") print(layout_template) User Layout: {'header': {'logo': 'MyApp', 'menu': ['Home', 'Profile', 'Logout']}, 'sidebar': {'links': ['Dashboard', 'Settings', 'Billing']}, 'settings': {'theme': 'dark', 'language': 'en'}} Template Layout (unchanged): {'header': {'logo': 'MyApp', 'menu': ['Home', 'Profile', 'Logout']}, 'sidebar': {'links': ['Dashboard', 'Settings', 'Billing']}, 'settings': {'theme': 'light', 'language': 'en'}} So why this works copy.copy() creates a new top-level dictionary, so user_layout["settings"] is a separate object that we can safely modify. The larger, static objects like header and sidebar are shared between layouts. That’s good no need to duplicate them in memory. It’s a practical trade-off, use shallow copy when parts of your data are meant to stay

Copying objects in Python may seem like a simple task. You’ve got a list, or maybe a dictionary, and you want a copy of it. Easy, right? Just assign it to a new variable or maybe use copy(). But under the hood, things can get tricky, especially when your data is nested or mutable. That's where the concepts of shallow and deep copies come in.

In this post, we’ll break down what these terms really mean, why choosing the right one matters, and show real-world examples of how copying can either save or sabotage your program.

Why copying objects deserves more attention than you think

Python doesn’t always behave the way newcomers expect when it comes to copying data structures. When you assign one variable to another, you’re not copying the object, you’re just copying the reference. That means both variables point to the same object in memory.

the_original = [1, 2, 3]

the_copy = the_original

the_copy[0] = 999

print(the_original) # [999, 2, 3]

print(the_copy) # [999, 2, 3]

Yep. Changing the_copy also changed the_original. That’s because they’re actually the same list.

To really clone an object, Python offers two approaches:

- Shallow copy: Copies the outer object, but not the nested objects.

- Deep copy: Recursively copies everything inside, making a true clone.

Why you need to know your copying options

When working with complex data (think lists of dictionaries, or class instances that reference each other), copying incorrectly can lead to bugs that are super hard to trace.

Imagine writing a function that modifies a list passed as an argument, expecting to work with a separate copy, but accidentally changing the original data instead.

Copying looks simple, but choosing the wrong method can introduce silent data corruption, hard-to-reproduce bugs, or unnecessary memory usage.

So, let’s break it all down:

What is a shallow copy?

A shallow copy creates a new object, but instead of copying nested objects inside, it just copies the references to them.

You can create a shallow copy with:

- The

copy()method (for lists and dicts) - The

copy.copy()function from thecopymodule

Let’s look at a simple example:

import copy

the_original = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

the_shallow = copy.copy(the_original)

the_shallow[0][0] = 999

print(the_original) # [[999, 2], [3, 4]]

print(the_shallow) # [[999, 2], [3, 4]]

Only the outer list was copied. The inner lists still point to the same memory.

What is a deep copy?

A deep copy, created with copy.deepcopy(), duplicates everything not just the container, but all nested elements too.

This gives you an entirely separate object tree that you can modify without fear of affecting the original.

import copy

the_original = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

the_deep = copy.deepcopy(the_original)

the_deep[0][0] = 999

print(the_original) # [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

print(the_deep) # [[999, 2], [3, 4]]

Now we’re talking! The original stays safe.

Case Study 1: When shallow copy i*s* the right choice

Let’s say you’re building a GUI-based app where each user gets a personalized page layout. Each layout includes a header, a sidebar, and a settings section. The header and sidebar are exactly the same across all users they contain static elements like logos and navigation menus. Only the settings section varies per user like theme and language preferences.

In this case, you want to share most of the structure between users to save memory and initialization time. You just need a different settings object per user.

So… enter shallow copy.

import copy

# Shared UI components (assumed large and immutable)

header = {"logo": "MyApp", "menu": ["Home", "Profile", "Logout"]}

sidebar = {"links": ["Dashboard", "Settings", "Billing"]}

# Base layout template

layout_template = {

"header": header,

"sidebar": sidebar,

"settings": {"theme": "light", "language": "en"}

}

# Create a user-specific layout using shallow copy

user_layout = copy.copy(layout_template)

# Customize just the settings for this user

user_layout["settings"]["theme"] = "dark"

print("User Layout:")

print(user_layout)

print("\nTemplate Layout (unchanged):")

print(layout_template)

User Layout:

{'header': {'logo': 'MyApp', 'menu': ['Home', 'Profile', 'Logout']},

'sidebar': {'links': ['Dashboard', 'Settings', 'Billing']},

'settings': {'theme': 'dark', 'language': 'en'}}

Template Layout (unchanged):

{'header': {'logo': 'MyApp', 'menu': ['Home', 'Profile', 'Logout']},

'sidebar': {'links': ['Dashboard', 'Settings', 'Billing']},

'settings': {'theme': 'light', 'language': 'en'}}

So why this works

-

copy.copy()creates a new top-level dictionary, souser_layout["settings"]is a separate object that we can safely modify. - The larger, static objects like

headerandsidebarare shared between layouts. That’s good no need to duplicate them in memory.

It’s a practical trade-off, use shallow copy when parts of your data are meant to stay shared, and only specific sections, like settings, need to change.

Case Study 2: When shallow copy breaks things

Let’s say you have an inventory list for a warehouse, where each item has quantity and attributes.

import copy

inventory = [

{"item": "apple", "qty": 50},

{"item": "banana", "qty": 100}

]

# Shallow copy before simulating shipment

shipment = copy.copy(inventory)

shipment[0]["qty"] -= 10 # 10 apples shipped

print("Inventory:", inventory)

print("Shipment:", shipment)

Inventory: [{'item': 'apple', 'qty': 40}, {'item': 'banana', 'qty': 100}]

Shipment: [{'item': 'apple', 'qty': 40}, {'item': 'banana', 'qty': 100}]

Even though we made a copy, the inventory got modified. That’s because the dictionaries inside the list were still shared references.

Case Study 3: When deep copy is a mistake

Suppose you’re building a game where all enemy characters share the same configuration object:

class Config:

def __init__(self):

self.aggressiveness = 5

class Enemy:

def __init__(self, config):

self.config = config

shared_config = Config()

enemy1 = Enemy(shared_config)

enemy2 = copy.deepcopy(enemy1)

enemy1.config.aggressiveness = 10

print(enemy2.config.aggressiveness) # Still 5

Here’s the problem: if you wanted all enemies to share the same config and respond to real-time tuning, deep copy breaks that connection.

Sometimes you want references to stay intact and deep copying breaks that intention.

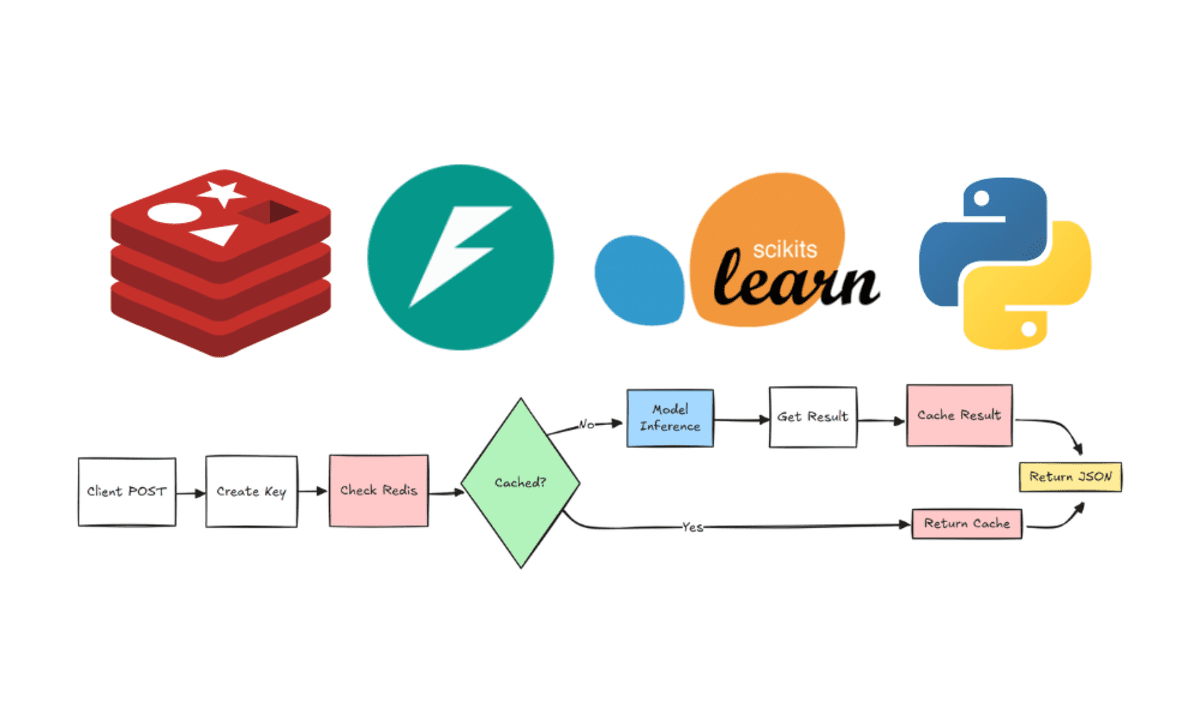

So, which copying method should you use?

Here’s a quick cheat sheet:

| Situation | Use |

|---|---|

| Only need a top-level copy | Shallow Copy |

| Need a full, independent object | Deep Copy |

| Working with nested structures | Deep Copy |

| Performance-sensitive operations | Shallow (if safe) |

| Need shared references | No copy or shallow |

Remember: copying isn’t just a syntax decision it reflects your data ownership strategy.

Final thoughts

Copying in Python might look like a minor topic, but it touches nearly every aspect of writing maintainable, bug-free code especially when you’re dealing with mutable, nested, or shared data.

Next time you’re about to write = or copy(), take a second to ask:

“Am I copying a structure, or just its pointer?”

Knowing the difference between shallow and deep copies can save hours of debugging and give you more control over your data’s lifecycle.

Happy coding, and may your references always behave as expected!

![[The AI Show Episode 143]: ChatGPT Revenue Surge, New AGI Timelines, Amazon’s AI Agent, Claude for Education, Model Context Protocol & LLMs Pass the Turing Test](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20143%20cover.png)

![[FREE EBOOKS] AI and Business Rule Engines for Excel Power Users, Machine Learning Hero & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Hostinger Horizons lets you effortlessly turn ideas into web apps without coding [10% off]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/04/IMG_1551.png?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![This new Google TV streaming dongle looks just like a Chromecast [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/04/thomson-cast-150-google-tv-1.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Drops New Immersive Adventure Episode for Vision Pro: 'Hill Climb' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97133/97133/97133-640.jpg)

![Most iPhones Sold in the U.S. Will Be Made in India by 2026 [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97130/97130/97130-640.jpg)