How LLMs 'Know' Stuff

One of the more quietly frustrating things about using large language models is realizing they don't actually know what you're talking about. They sound like they do. They generate confident, fluent text that gives the impression of comprehension. But behind the curtain, it's a bunch of math trying to guess the following words based on patterns it's seen before. But even if the model doesn't "know" anything in the human sense, it still produces helpful (sometimes even excellent) output. So, where does that output come from? What's shaping it? 1. Latent Knowledge What the model learned before you showed up. Every model is trained on a massive pile of text: books, websites, public forums, codebases, documentation, Wikipedia, and way too many Reddit arguments. I tend to think of it as 'the computers read the internet.' That training process creates what's called latent knowledge—the model's internal sense of how language works, and what tends to go with what. It doesn't "remember" specific documents. It has no file system. What it has is a set of statistical associations baked into its weights. It knows that the phrase "how to boil an egg" is likely followed by steps. It knows that Python code looks a certain way. It knows that banana bread is a thing. This baked-in knowledge is broad and surprisingly flexible. You can ask a well-formed question and often get a decent answer without giving it any context at all. But it's also static. It can't learn new things in real time. It doesn't know what happened yesterday unless yesterday happened in its training data, or it has a web search tool. 2. Initial Context What you tell it upfront. When you open a new chat with an llm, it waits for you to set the direction and tone of the conversation. When you send a prompt, you're shaping what the model sees; what statistical paths it chooses to generate a response. That prompt and any setup or documents you include or attach are the initial context. It's the only thing the model has to work with besides its training. If your initial context is clear, well-structured, and includes relevant constraints, you give the model more to work with than its internal hunches. But if your prompt is vague or underspecified, the model will fill in the blanks using its latent knowledge. Might be good; might be based on a Spirk fanfic from 1976. This is where people overestimate the model's awareness. You might assume that if you paste in a document or mention something once in paragraph four, the model "knows" it. Not always. Not unless it's recent, repeated, or phrased clearly enough to stick. 3. Conversational Context What gets built over time. If you're working in a chat interface, every message you send becomes part of the conversation history. That's conversational context—an evolving thread of instructions, clarifications, feedback, and bad follow-up questions. (We've all done it.) This ongoing exchange feels collaborative. And it can be. But here's the thing people miss: LLMs don't track conversation like a human. They reread the most recent portions of the thread every time and try to predict what comes next. Unless you explicitly tell it, it doesn't "know" that it made a mistake two messages ago. Over the course of the conversation, the meaning of the words will get subtly reinforced or become more ambiguous. If the conversation gets long, the early stuff starts to fade—not because it's forgotten, but because it's buried. Here's how all of this flows together: Proximity Bias Proximity bias plays a big role in the model's output. The model pays attention to everything in the context window, but the closer something is to the end of the conversation, the more influence it tends to have. In plain terms, the most recent messages often shape the output the most. This is why: A correction at the end of a long thread can override your original setup A prompt tweak halfway through a conversation can shift tone or strategy Important details buried early in the thread can get ignored entirely The model isn't malicious. It's simple. It reacts to what's in front of it, but mainly to the most recent words. Where This Leaves Us When an LLM gives you a weird answer, it's tempting to blame the model. But more often, it's reacting to the context you gave it (or didn't). Its "knowledge" comes from three sources: What the model learned during training (latent knowledge) What you gave up front (initial context) What's accumulated in the chat (conversational context) And those don't carry equal weight. As your conversation unfolds, recent messages tend to dominate. Earlier instructions fade. Meaning drifts. So if you're aiming for clarity or consistency, don't tack a final question onto a long chat and hope for the best. Pause. Ask it to summarize what you need as a new prompt, and validate that it looks correct.

One of the more quietly frustrating things about using large language models is realizing they don't actually know what you're talking about.

They sound like they do. They generate confident, fluent text that gives the impression of comprehension. But behind the curtain, it's a bunch of math trying to guess the following words based on patterns it's seen before.

But even if the model doesn't "know" anything in the human sense, it still produces helpful (sometimes even excellent) output. So, where does that output come from? What's shaping it?

1. Latent Knowledge

What the model learned before you showed up.

Every model is trained on a massive pile of text: books, websites, public forums, codebases, documentation, Wikipedia, and way too many Reddit arguments. I tend to think of it as 'the computers read the internet.' That training process creates what's called latent knowledge—the model's internal sense of how language works, and what tends to go with what.

It doesn't "remember" specific documents. It has no file system. What it has is a set of statistical associations baked into its weights. It knows that the phrase "how to boil an egg" is likely followed by steps. It knows that Python code looks a certain way. It knows that banana bread is a thing.

This baked-in knowledge is broad and surprisingly flexible. You can ask a well-formed question and often get a decent answer without giving it any context at all. But it's also static. It can't learn new things in real time. It doesn't know what happened yesterday unless yesterday happened in its training data, or it has a web search tool.

2. Initial Context

What you tell it upfront.

When you open a new chat with an llm, it waits for you to set the direction and tone of the conversation. When you send a prompt, you're shaping what the model sees; what statistical paths it chooses to generate a response. That prompt and any setup or documents you include or attach are the initial context. It's the only thing the model has to work with besides its training.

If your initial context is clear, well-structured, and includes relevant constraints, you give the model more to work with than its internal hunches. But if your prompt is vague or underspecified, the model will fill in the blanks using its latent knowledge. Might be good; might be based on a Spirk fanfic from 1976.

This is where people overestimate the model's awareness. You might assume that if you paste in a document or mention something once in paragraph four, the model "knows" it. Not always. Not unless it's recent, repeated, or phrased clearly enough to stick.

3. Conversational Context

What gets built over time.

If you're working in a chat interface, every message you send becomes part of the conversation history. That's conversational context—an evolving thread of instructions, clarifications, feedback, and bad follow-up questions. (We've all done it.)

This ongoing exchange feels collaborative. And it can be. But here's the thing people miss:

LLMs don't track conversation like a human. They reread the most recent portions of the thread every time and try to predict what comes next.

Unless you explicitly tell it, it doesn't "know" that it made a mistake two messages ago. Over the course of the conversation, the meaning of the words will get subtly reinforced or become more ambiguous. If the conversation gets long, the early stuff starts to fade—not because it's forgotten, but because it's buried.

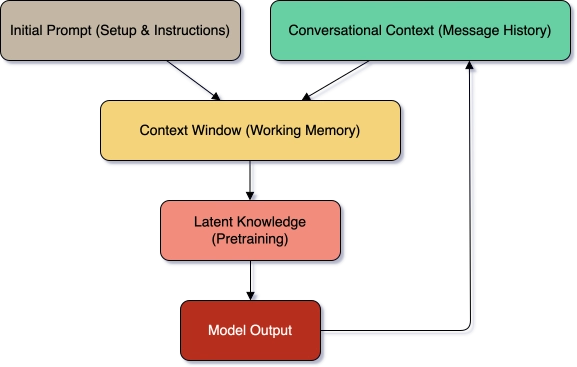

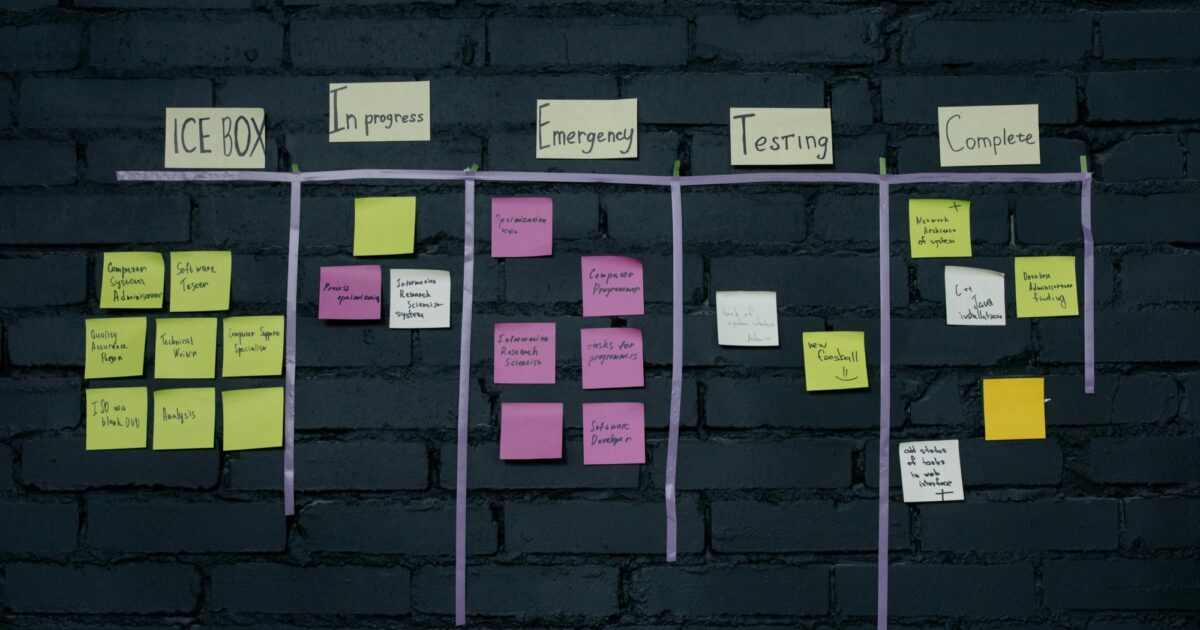

Here's how all of this flows together:

Proximity Bias

Proximity bias plays a big role in the model's output. The model pays attention to everything in the context window, but the closer something is to the end of the conversation, the more influence it tends to have. In plain terms, the most recent messages often shape the output the most.

This is why:

- A correction at the end of a long thread can override your original setup

- A prompt tweak halfway through a conversation can shift tone or strategy

- Important details buried early in the thread can get ignored entirely

The model isn't malicious. It's simple. It reacts to what's in front of it, but mainly to the most recent words.

Where This Leaves Us

When an LLM gives you a weird answer, it's tempting to blame the model. But more often, it's reacting to the context you gave it (or didn't).

Its "knowledge" comes from three sources:

- What the model learned during training (latent knowledge)

- What you gave up front (initial context)

- What's accumulated in the chat (conversational context)

And those don't carry equal weight. As your conversation unfolds, recent messages tend to dominate. Earlier instructions fade. Meaning drifts.

So if you're aiming for clarity or consistency, don't tack a final question onto a long chat and hope for the best. Pause. Ask it to summarize what you need as a new prompt, and validate that it looks correct. Start fresh with a structured prompt that reflects what you need.

LLMs don't know what you mean—but they'll try to guess. The more clearly you understand and express your own intent, the more likely they'll get it right.

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The All-in-One Microsoft Office Pro 2019 for Windows: Lifetime License + Windows 11 Pro Bundle (89% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Is this too much for a modular monolith system? [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/pYL1nsfg.png)

_Andreas_Prott_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![What features do you get with Gemini Advanced? [April 2025]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/02/gemini-advanced-cover.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Shares Official Trailer for 'Long Way Home' Starring Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97069/97069/97069-640.jpg)

![Apple Watch Series 10 Back On Sale for $299! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96657/96657/96657-640.jpg)

![EU Postpones Apple App Store Fines Amid Tariff Negotiations [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97068/97068/97068-640.jpg)

![Apple Slips to Fifth in China's Smartphone Market with 9% Decline [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97065/97065/97065-640.jpg)