How artists are bracing for Trump’s ‘golden age’ of arts and culture

In a February 2025 Truth Social post, President Donald Trump declared a “Golden Age in Arts and Culture.” So far, this “golden age” has entailed an executive order calling for the federal agency that funds local museums and libraries to be dismantled, with most grants rescinded. The Trump administration has forbidden federal arts funding from going to artists who promote what the administration calls “gender ideology.” There’s been a purge of the board of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, with Trump appointing himself chair. And the administration has canceled National Endowment for the Humanities grants. Suffice it to say, many artists and arts organizations across the U.S. are worried: Will government arts funding dry up? Do these cuts signal a new war on arts and culture? How do artists make it through this period of change? As scholars who study the arts, activism and policy, we’re watching the latest developments with apprehension. But we think it’s important to point out that while the U.S. government has never been a global leader of arts funding, American artists have always been innovative, creative and scrappy during times of political turmoil. A rocky relationship with the arts For much of the country’s early history, government funding for the arts was rarely guaranteed or stable. After the Civil War, the Second Industrial Revolution facilitated massive concentrations of wealth, in what became known as the the Gilded Age. Private arts funding soared during this period, with some titans of industry, such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, seeing it as their duty to build museums, theaters and libraries for the public. The heavy reliance on private funding for the arts troubled some Americans, who feared these institutions would become too exposed to the whims of the wealthy. In response, Progressive Era activists and politicians argued that it was the government’s responsibility to build arts spaces accessible to all Americans. Efforts to fund the arts expanded with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, as the country was reeling from the Great Depression. From 1935 to 1943, the Works Progress Administration provided jobs with stable wages for artists through the Federal Art Project. However, Congress famously terminated the program in response to a 1937 production of “The Revolt of the Beavers,” which conservative politicians denounced for containing overt Marxist themes. Nonetheless, over the ensuing decades, the federal government generally signaled its support for the arts. Congress established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1965 to fund arts organizations and artists. And since 1972, the General Services Administration has commissioned public art for federal buildings and organized a registry of prospective artists. The NEA gave US$8.4 million in direct funding to artists in 1989 via fellowships and grants. This might be considered the high-water mark for unrestricted government funding for individual artists. By the 1980s, sexuality, drugs and American morality had become hot-button political issues. The arts, from music to theater, were at the center of this culture war. Pressure escalated in 1989 when conservative leaders contested two NEA-funded exhibitions featuring work by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, which they deemed homoerotic and anti-Christian. In 1990, Congress instated a “decency clause” guiding all future NEA work. When Republicans regained control of Congress in 1994, they slashed direct funding for the arts. With direct funding to artists largely eliminated, today’s artists can indirectly receive federal government support through federal arts agency grants, which are given to arts organizations that then dole out a portion to artists. Local and state government agencies also provide small amounts of direct support for artists. The stage of democracy Artists and arts organizations have a long legacy of persistence and strategic organizing during periods of political and economic upheaval. In the pre-Revolutionary colonies, representatives of the British government banned theatrical performances to discourage revolutionary action. In response, activist playwrights organized underground parlor dramas and informal dramatic readings to keep arts-based activism alive. Activist theater continued into the antebellum period for the purposes of promoting the abolitionist cause. These dramas, often organized by women, would take place in living rooms, outside of public view. The clandestine staged readings – the most famous of which was written by one of the earliest Black American playwrights, William Wells Brown – seeded enthusiasm and solidarity for the antislavery cause. These privately staged readings took place alongside public performances and lectures. Craft the world you want Dozens of experimental schools like the Highlan

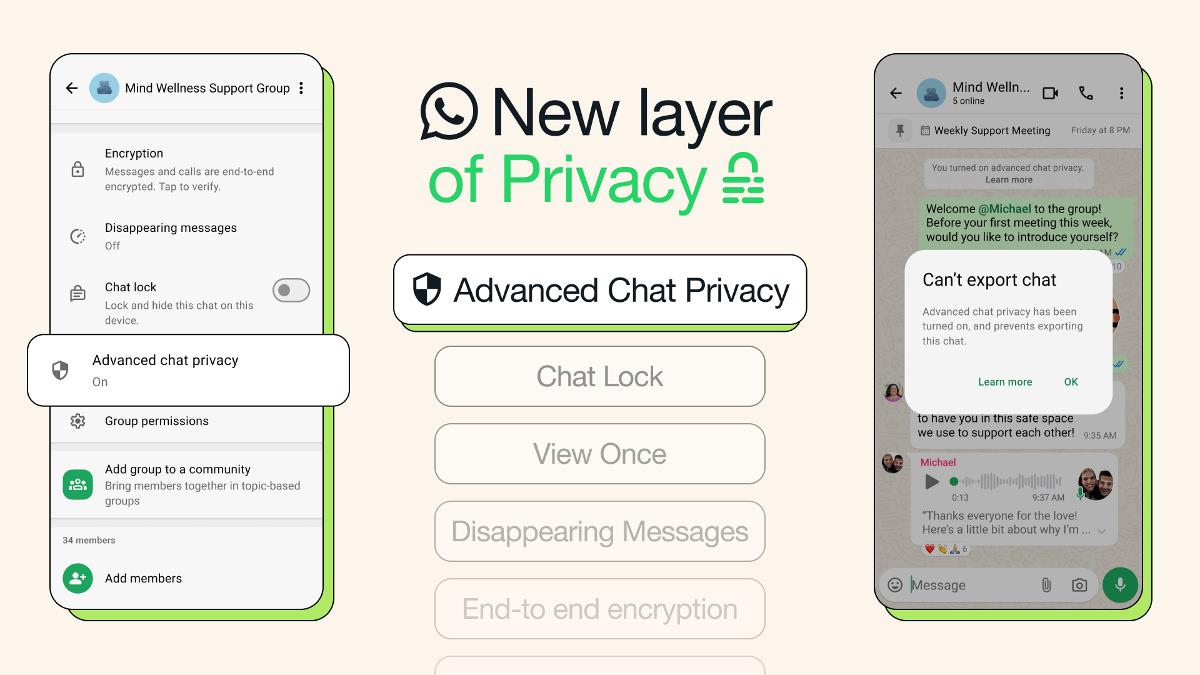

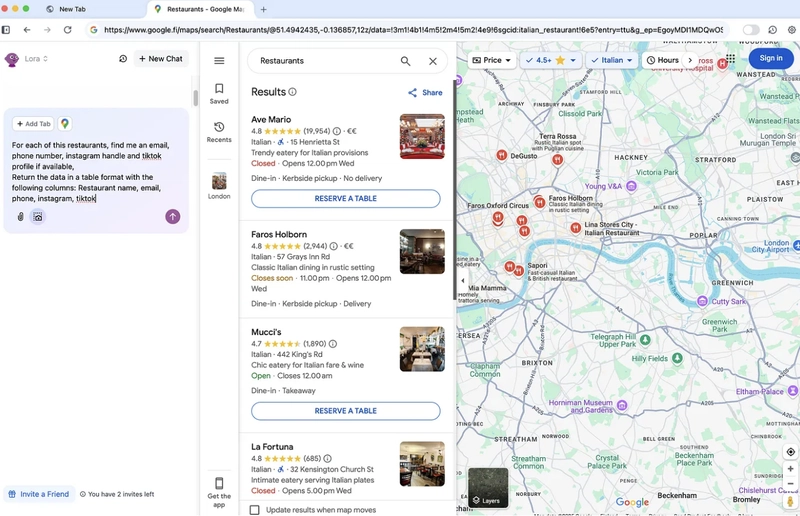

In a February 2025 Truth Social post, President Donald Trump declared a “Golden Age in Arts and Culture.”

So far, this “golden age” has entailed an executive order calling for the federal agency that funds local museums and libraries to be dismantled, with most grants rescinded. The Trump administration has forbidden federal arts funding from going to artists who promote what the administration calls “gender ideology.” There’s been a purge of the board of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, with Trump appointing himself chair. And the administration has canceled National Endowment for the Humanities grants.

Suffice it to say, many artists and arts organizations across the U.S. are worried: Will government arts funding dry up? Do these cuts signal a new war on arts and culture? How do artists make it through this period of change?

As scholars who study the arts, activism and policy, we’re watching the latest developments with apprehension. But we think it’s important to point out that while the U.S. government has never been a global leader of arts funding, American artists have always been innovative, creative and scrappy during times of political turmoil.

A rocky relationship with the arts

For much of the country’s early history, government funding for the arts was rarely guaranteed or stable.

After the Civil War, the Second Industrial Revolution facilitated massive concentrations of wealth, in what became known as the the Gilded Age. Private arts funding soared during this period, with some titans of industry, such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, seeing it as their duty to build museums, theaters and libraries for the public. The heavy reliance on private funding for the arts troubled some Americans, who feared these institutions would become too exposed to the whims of the wealthy.

In response, Progressive Era activists and politicians argued that it was the government’s responsibility to build arts spaces accessible to all Americans.

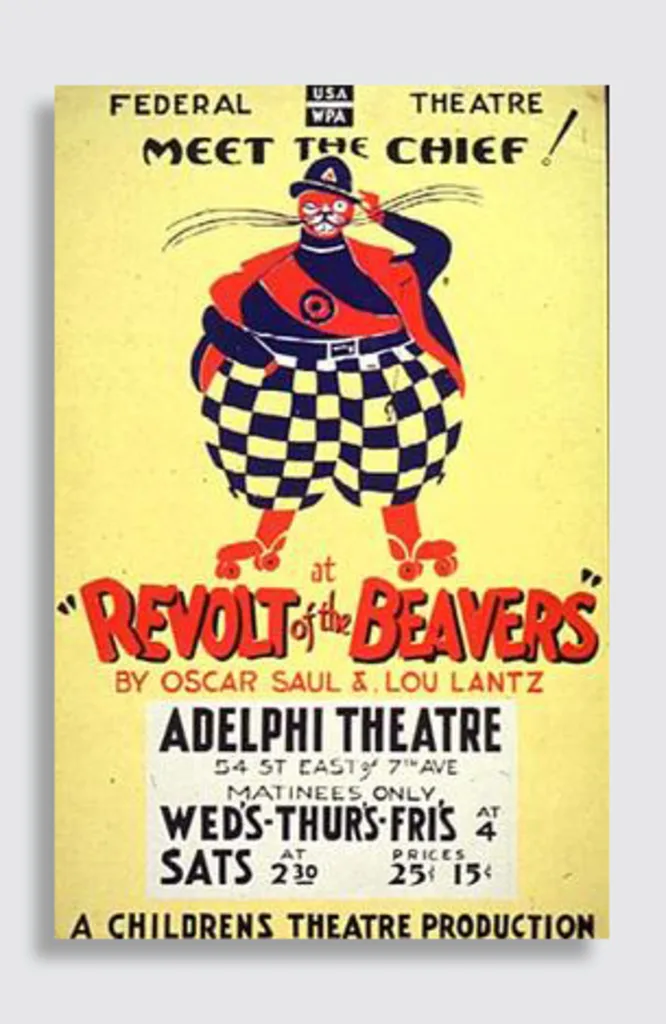

Efforts to fund the arts expanded with the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, as the country was reeling from the Great Depression. From 1935 to 1943, the Works Progress Administration provided jobs with stable wages for artists through the Federal Art Project. However, Congress famously terminated the program in response to a 1937 production of “The Revolt of the Beavers,” which conservative politicians denounced for containing overt Marxist themes.

Nonetheless, over the ensuing decades, the federal government generally signaled its support for the arts.

Congress established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1965 to fund arts organizations and artists. And since 1972, the General Services Administration has commissioned public art for federal buildings and organized a registry of prospective artists.

The NEA gave US$8.4 million in direct funding to artists in 1989 via fellowships and grants. This might be considered the high-water mark for unrestricted government funding for individual artists.

By the 1980s, sexuality, drugs and American morality had become hot-button political issues. The arts, from music to theater, were at the center of this culture war. Pressure escalated in 1989 when conservative leaders contested two NEA-funded exhibitions featuring work by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, which they deemed homoerotic and anti-Christian. In 1990, Congress instated a “decency clause” guiding all future NEA work. When Republicans regained control of Congress in 1994, they slashed direct funding for the arts.

With direct funding to artists largely eliminated, today’s artists can indirectly receive federal government support through federal arts agency grants, which are given to arts organizations that then dole out a portion to artists. Local and state government agencies also provide small amounts of direct support for artists.

The stage of democracy

Artists and arts organizations have a long legacy of persistence and strategic organizing during periods of political and economic upheaval.

In the pre-Revolutionary colonies, representatives of the British government banned theatrical performances to discourage revolutionary action. In response, activist playwrights organized underground parlor dramas and informal dramatic readings to keep arts-based activism alive.

Activist theater continued into the antebellum period for the purposes of promoting the abolitionist cause.

These dramas, often organized by women, would take place in living rooms, outside of public view. The clandestine staged readings – the most famous of which was written by one of the earliest Black American playwrights, William Wells Brown – seeded enthusiasm and solidarity for the antislavery cause. These privately staged readings took place alongside public performances and lectures.

Craft the world you want

Dozens of experimental schools like the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee and Commonwealth College in Arkansas were founded in the 1920s and 1930s to train activists.

Supporting adult learners of all ages – but specifically young adults – they initially focused on arts-based techniques for training workers in labor activism. For example, students wrote short plays based on their experiences of factory work. In their rehearsals and performances, they imagined endings in which workers triumphed over cruel bosses.

Many programs were residential, rural and embraced early versions of mutual aid, where artists and activists support one another directly through pooling money and resources. Tuition was minimal and generally provided directly from labor organizations and allies, including the American Fund for Public Service. Most teachers were volunteers, and the learning communities often farmed to cover basic necessities.

Although these institutions faced perpetual threats from local governments and even the FBI, these communal schools became testing grounds for social change. Some programs even became training sites for civil rights activists.

Curate the world you need

Black artists have long created spaces for community connection and career development. The Great Migration brought many Black American artists and thinkers to New York City, famously spurring the Harlem Renaissance, which lasted from the end of World War I through the 1920s. During this period, the neighborhood became a fountain of culture, with Black artists producing countless plays, books, music and other visionary works.

This legacy continued at Just Above Midtown, or JAM, a gallery and arts laboratory led by Linda Goode Bryant from 1974 through 1986 on West 57th Street in Manhattan.

At the time, arts organizations primarily supported artwork by white men. In response, Goode Bryant launched JAM to create a space that supported and celebrated artists of color. JAM provided arts business workshops, cultivated collaborations and launched the careers of Black artists such as David Hammons and Lorraine O’Grady.

The future is now

Whether or not they realize it, many artists and arts organizations today are integrating lessons from the past.

In recent years, they’ve promoted the unionization of museum workers and created local mutual aid networks such as the Museum Workers Relief Fund, which was one of many groups fundraising for arts workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. They’re building networks of financial support to share space and money with other artists and arts organizations. And they’re forming cultural land trusts, which create land cooperatives where artists can work and live with one another.

What’s more, new philanthropic models are reshaping arts funding by elevating the perspectives of artists, rather than those of wealthy funders. CAST in San Francisco helps arts organizations find affordable gallery and performance spaces. The Community and Cultural Power Fund uses a trust-based philanthropy model that allows artists and community members to decide who receives future grants. The Ruth Foundation for the Arts makes artists the decision-makers in giving grants to arts organizations.

While the current challenges are unprecedented – and funding threats will likely reshape arts organizations and further limit direct support for artists – we’re confident that the arts will persist with or without government support.

Johanna K. Taylor is an associate professor at The Design School at Arizona State University.

Mary McAvoy is an associate professor of theatre at Arizona State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] Sterling Stock Picker: Lifetime Subscription (85% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

_Olekcii_Mach_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![M4 MacBook Air Drops to New All-Time Low of $912 [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97108/97108/97108-640.jpg)

![New iPhone 17 Dummy Models Surface in Black and White [Images]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97106/97106/97106-640.jpg)