This toxic chemical is leaking out of nondescript warehouses across the country. Almost no one knows about it

By January 2018, Vanessa Dominguez and her husband had been flirting with moving to a different neighborhood in El Paso, Texas, for a few years. Their daughter was enrolled in one of the best elementary schools in the county, but because the family lived just outside the district’s boundary, her position was tenuous. Administrators could decide to return her to her home district at any moment. Moving closer would guarantee her spot. And when their landlord notified Dominguez that she wanted to double their rent, she and her husband felt more urgency to make their move. Finally, the opportunity came. Dominguez’s boss owned a three-bedroom, two-bathroom house in Ranchos del Sol, an upper-middle-class neighborhood in east El Paso, and was looking for a new tenant. With a kitchen island, high ceilings, and a park across the street where kids often played soccer, the house was perfect for the young family. Most importantly, the property was within the school district’s boundaries. “The property as a whole seemed attractive, and the neighborhood seemed pretty calm,” Dominguez recalled. After they moved in, Dominguez’s daughter quickly took to running around in the backyard, which featured a cherry blossom tree, and the family often grilled outside. Dominguez barely noticed the warehouse just beyond the cobblestone wall at the back. It really wasn’t until the COVID-19 stay-at-home mandate in 2020 that she noticed the stream of trucks pulling in and out of the facility. Sometimes, she would hear the rumble of 18-wheelers as early as 6:30 a.m. Still, she made little of it. She didn’t realize that the warehouse was owned by Cardinal Health, one of the largest medical device distributors in the country, or that it’s part of a vast supply chain that the American public relies on to receive proper medical care. But for Dominguez and her family, what seemed little more than a minor nuisance was actually a sprawling menace—one that a Grist data analysis found was exposing them to exceedingly high levels of a dangerous chemical. Cardinal Health uses that warehouse, and another one across town, to store medical devices that have been sterilized with ethylene oxide. Among the thousands of compounds released every day from polluting facilities, it’s among the most toxic, responsible for more than half of all excess cancer risk from industrial operations nationwide. Long-term exposure to the chemical has been linked to cancers of the breast and lymph nodes, and short-term exposure can cause irritation of the nasal cavity, shortness of breath, wheezing, and bronchial constriction. Dominguez’s family would go on to experience some of these symptoms, but only years later would they tie it to ethylene oxide exposure. Warehouses like the ones in El Paso are ubiquitous throughout the country. Through records requests and on-the-ground reporting, Grist has identified at least 30 warehouses across the country that definitely emit some amount of ethylene oxide. They are used by companies such as Boston Scientific, ConMed, and Becton Dickinson, as well as Cardinal Health. And they are not restricted to industrial parts of towns—they are near schools and playgrounds, gyms and apartment complexes. From the outside, the warehouses don’t attract attention. They look like any other distribution center. Many occupy hundreds of thousands of square feet, and dozens of trucks pull in and out every day. But when these facilities load, unload, and move medical products, they belch ethylene oxide into the air. Most residents nearby have no idea that the nondescript buildings are a source of toxic pollution. Neither do most truck drivers, who are often hired on a contract basis, or many of the workers employed at the warehouses. Grist identified the country’s top medical device manufacturers and distributors, including Cardinal Health, Medline, Becton Dickinson, and Owens & Minor, and collated a list of the more than 100 known warehouses that they own or use. Some of these companies have reported to state or federal regulators that they operate at least one distribution center that stores products sterilized with ethylene oxide. Others were identified in person by Grist reporters as recipients of products from sterilization facilities. But since companies use multiple sterilization methods, it’s unclear whether each of these emits ethylene oxide. However, Grist still chose to publish the information to demonstrate the scale of the potential problem: There are almost certainly dozens, if not hundreds, more warehouses than the 30 we are certain about—and thousands more workers unknowingly exposed to ethylene oxide. Identifying these warehouses and the 30 or so that emit some amount of ethylene oxide was a laborious process, in part because information about these facilities isn’t readily available. Grist reporters staked out sterilization facilities, spoke to truck drivers and warehouse workers, and combed through pro

By January 2018, Vanessa Dominguez and her husband had been flirting with moving to a different neighborhood in El Paso, Texas, for a few years. Their daughter was enrolled in one of the best elementary schools in the county, but because the family lived just outside the district’s boundary, her position was tenuous. Administrators could decide to return her to her home district at any moment. Moving closer would guarantee her spot. And when their landlord notified Dominguez that she wanted to double their rent, she and her husband felt more urgency to make their move.

Finally, the opportunity came. Dominguez’s boss owned a three-bedroom, two-bathroom house in Ranchos del Sol, an upper-middle-class neighborhood in east El Paso, and was looking for a new tenant.

With a kitchen island, high ceilings, and a park across the street where kids often played soccer, the house was perfect for the young family. Most importantly, the property was within the school district’s boundaries.

“The property as a whole seemed attractive, and the neighborhood seemed pretty calm,” Dominguez recalled.

After they moved in, Dominguez’s daughter quickly took to running around in the backyard, which featured a cherry blossom tree, and the family often grilled outside. Dominguez barely noticed the warehouse just beyond the cobblestone wall at the back. It really wasn’t until the COVID-19 stay-at-home mandate in 2020 that she noticed the stream of trucks pulling in and out of the facility. Sometimes, she would hear the rumble of 18-wheelers as early as 6:30 a.m.

Still, she made little of it. She didn’t realize that the warehouse was owned by Cardinal Health, one of the largest medical device distributors in the country, or that it’s part of a vast supply chain that the American public relies on to receive proper medical care.

But for Dominguez and her family, what seemed little more than a minor nuisance was actually a sprawling menace—one that a Grist data analysis found was exposing them to exceedingly high levels of a dangerous chemical.

Cardinal Health uses that warehouse, and another one across town, to store medical devices that have been sterilized with ethylene oxide. Among the thousands of compounds released every day from polluting facilities, it’s among the most toxic, responsible for more than half of all excess cancer risk from industrial operations nationwide. Long-term exposure to the chemical has been linked to cancers of the breast and lymph nodes, and short-term exposure can cause irritation of the nasal cavity, shortness of breath, wheezing, and bronchial constriction. Dominguez’s family would go on to experience some of these symptoms, but only years later would they tie it to ethylene oxide exposure.

Warehouses like the ones in El Paso are ubiquitous throughout the country. Through records requests and on-the-ground reporting, Grist has identified at least 30 warehouses across the country that definitely emit some amount of ethylene oxide. They are used by companies such as Boston Scientific, ConMed, and Becton Dickinson, as well as Cardinal Health. And they are not restricted to industrial parts of towns—they are near schools and playgrounds, gyms and apartment complexes. From the outside, the warehouses don’t attract attention. They look like any other distribution center. Many occupy hundreds of thousands of square feet, and dozens of trucks pull in and out every day. But when these facilities load, unload, and move medical products, they belch ethylene oxide into the air. Most residents nearby have no idea that the nondescript buildings are a source of toxic pollution. Neither do most truck drivers, who are often hired on a contract basis, or many of the workers employed at the warehouses.

Grist identified the country’s top medical device manufacturers and distributors, including Cardinal Health, Medline, Becton Dickinson, and Owens & Minor, and collated a list of the more than 100 known warehouses that they own or use. Some of these companies have reported to state or federal regulators that they operate at least one distribution center that stores products sterilized with ethylene oxide. Others were identified in person by Grist reporters as recipients of products from sterilization facilities. But since companies use multiple sterilization methods, it’s unclear whether each of these emits ethylene oxide. However, Grist still chose to publish the information to demonstrate the scale of the potential problem: There are almost certainly dozens, if not hundreds, more warehouses than the 30 we are certain about—and thousands more workers unknowingly exposed to ethylene oxide.

Identifying these warehouses and the 30 or so that emit some amount of ethylene oxide was a laborious process, in part because information about these facilities isn’t readily available. Grist reporters staked out sterilization facilities, spoke to truck drivers and warehouse workers, and combed through property databases.

The problem is “much bigger than we all assume,” said Rick Peltier, a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Massachusetts. “The lack of transparency of where these products go makes us worried.”

At the El Paso warehouse behind Dominguez’s house, Grist spoke to several Cardinal employees who had little knowledge of the risks of being exposed to ethylene oxide. Cardinal Health, which employs a largely Latino workforce at the warehouse, requires some laborers to wear monitors and keep windows and vents open for circulation. But the workers Grist spoke to were unsure what the company is monitoring for.

“I think it’s because of a kind of gas that we are breathing,” one material handler told Grist while on break. “I don’t know what it’s called.”

In response to the list of Cardinal warehouses that Grist identified, a spokesperson noted in a brief comment that the “majority of addresses you have listed are not even medical facilities” and that “the majority of the locations you’ve listed aren’t relevant to the topic you’re focused on.” However, the company did not provide specific information, and the warehouse locations were corroborated against materials available on the company’s website.

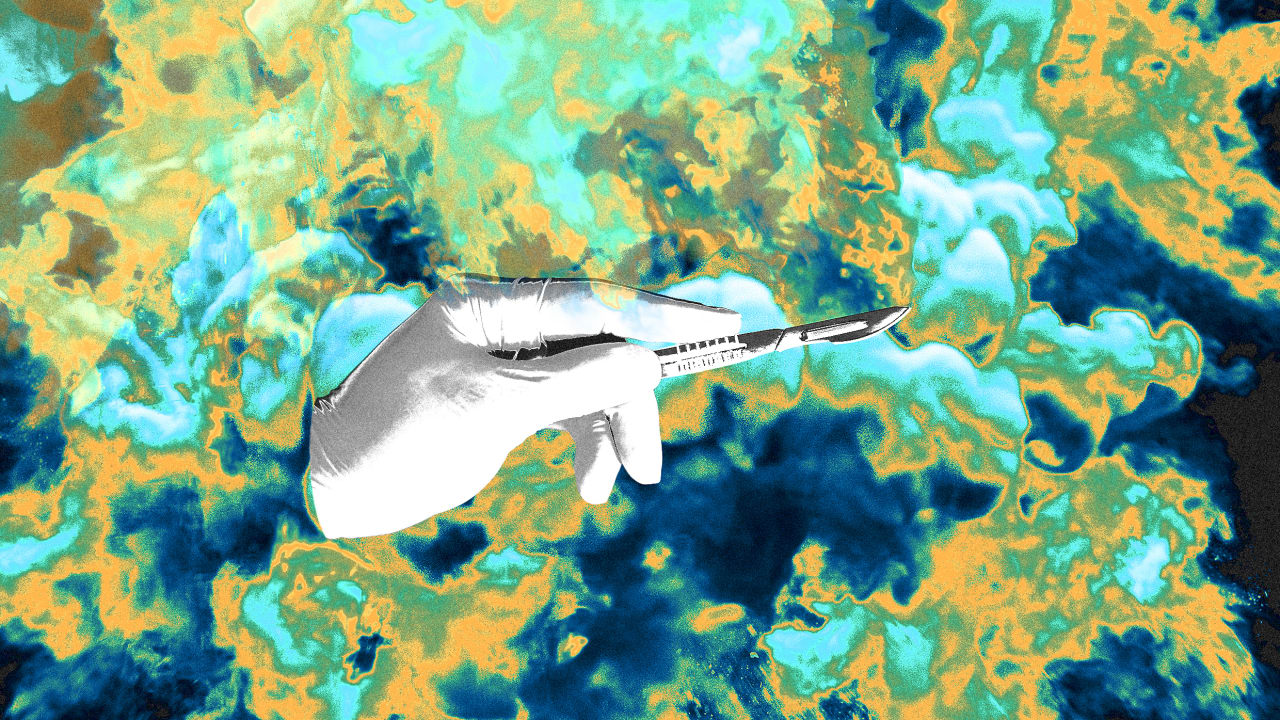

Cardinal’s operations extend across the U.S.-Mexico border. The company runs a manufacturing plant in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, where gauze, surgical gowns, drape sheets, scalpels, and other medical equipment are packaged into kits that provide “everything a doctor needs” to conduct a surgery, as one worker put it. The finished kits are trucked back to El Paso or to New Mexico, where they’re sterilized with ethylene oxide by third-party companies that Cardinal contracts with. Then, the products are trucked to one of the two Cardinal warehouses in El Paso, where they remain until they’re shipped to hospitals across the country. All along the way, in the trucks that transport them and the warehouses that store them, ethylene oxide releases from the surface of the sterilized devices, a process called off-gassing.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulates the facilities where medical devices are sterilized, controlling the processes and safety protocols to keep ethylene oxide emissions to safe levels. But for myriad reasons, the federal government—and the vast majority of states—has turned a blind eye to warehouses. That’s despite the fact that these storage centers sometimes release more ethylene oxide and pose a greater risk than sterilization facilities. Georgia regulators found that was the case in 2019, and a Grist analysis found the warehouse in Dominguez’s backyard posed a greater threat than the New Mexico sterilization facility that Cardinal receives products from.

“The EPA knows that the risks from ethylene oxide extend far beyond the walls of the sterilization facility,” said Jonathan Kalmuss-Katz, a lawyer at the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice who works on toxic chemicals, “that the chemical remains with the equipment when it is taken to a warehouse, and that it continues to be released, threatening workers and threatening surrounding communities.

“EPA had a legal obligation to address those risks,” he added.

In 2009, Cardinal Health reached out to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, the state environmental regulator, seeking permits for its ethylene oxide emissions. At the time, the chemical compound was not known to be as toxic as it is, and TCEQ officials asked few questions about the effect the emissions would have on residents nearby. Grist’s reporting indicates the company had no legal responsibility to inform state officials but appears to have done so as a responsible actor.

The company’s applications included a rudimentary diagram of a truck pulling up to a warehouse, an arrow pointing up into the air to denote ethylene oxide emissions from the facility, and a truck pulling out of the warehouse. “Due to the unloading of the tractor trailers, Cardinal Health is registering the fugitive EtO that escapes upon the opening of each of the tractor trailers,” it noted, using an abbreviation for ethylene oxide.

To calculate how much of the chemical escaped from trucks carrying sterilized products, Cardinal Health used an EPA model developed for wastewater treatment systems at TCEQ’s direction and multiplied the estimate by the number of trucks it expected would drop off products every year. It’s unclear why the agency instructed Cardinal Health to use a wastewater model for an air pollutant when alternatives existed, but these imprecise calculations led the company to figure that its warehouses emitted at least 479 pounds per year. TCEQ granted Cardinal’s permits without requiring the company to take measures to reduce the pollution or notify residents.

Four years later, the company appears to have made an effort to determine more precise calculations. In a 2013 experiment, the company fit blowers to a truck and measured the amount of ethylene oxide emitted—but withheld other relevant details, like when the measurements were taken and how many products the truck transported, from the documents it submitted to TCEQ. Cardinal found that, in the first five minutes after a truck pulls into the warehouse, the sterilized products off-gas ethylene oxide at their highest levels. But after five minutes, rather than dropping to zero, the off-gassing levels stayed steady at 7 parts per million for the next two hours.

Publicly available documents do not provide details about where the trucks were coming from, how many packages they held, or how long ago the products had been sterilized—crucial details that determine the rate at which ethylene oxide off-gases. If the medical devices in the truck that Cardinal observed traveled a short distance or if the truck was mostly empty when the experiment was conducted, the company could have vastly underestimated the emissions.

“The numbers they’re using are just science fiction,” said Peltier. “For something as powerful as a carcinogen like this, we ought to do better than making up numbers and just doing some hand-waving in order to demonstrate that you’re not imposing undue risk to the community.”

What’s more, the analyses did not take into account the ethylene oxide emissions once the products were moved inside Cardinal’s facilities.

Toxicologists have long identified ethylene oxide as a dangerous chemical. In 1982, the Women’s Occupational Health Resource Center at Columbia University published a series of fact sheets educating workers about the chemical, and in 1995, the Library of Congress released a study on the risks of using the gas to fumigate archival materials. However, it wasn’t until 2016 that the EPA updated ethylene oxide’s toxicity value, a figure that defines the probability of developing cancer if exposed to a certain amount of a chemical over the course of a lifetime. That year, the agency published a report reevaluating ethylene oxide utilizing an epidemiological study of more than 18,000 sterilization facility workers. The agency’s toxicologists determined the chemical to be 30 times more toxic to adults and 60 times more toxic to children than previously known.

Ethylene oxide, they determined, was one of the most toxic federally regulated air pollutants. Prolonged exposure was linked to elevated rates of lymphoma and breast cancer among the workers. In one study of 7,576 women who had spent at least one year working at a medical sterilization facility, 319 developed breast cancer. According to an analysis by the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists, roughly 14 million people in the U.S. live near a medical sterilization facility.

As a result of the EPA’s new evaluation, companies throughout the country came under greater scrutiny, with some sterilizers experiencing more frequent inspections. But regulators in Texas disputed the EPA’s report. In 2017, eight years after Cardinal Health’s first permit, officials with the TCEQ launched their own study of the chemical and set a threshold for ethylene oxide emissions that was 2,000 times more lenient than the EPA’s, setting off a legal battle that is still playing out in court. For warehouses, which do not receive federal scrutiny, TCEQ’s lenient attitude meant virtually no oversight.

By early 2020, people around the world had little energy for anything but the COVID-19 pandemic. And yet, the spike in demand for sterilized medical devices—and now masks—meant that more trucks with more materials passed through warehouses like the one just beyond Dominguez’s backyard.

To approximate how high her family’s exposure was to ethylene oxide during this period, Grist asked an expert air modeler to run Cardinal Health’s stated emissions through a mathematical model that simulates how pollution particles disperse throughout the atmosphere. (This same model is used by the EPA and companies—including Cardinal—during the permitting process.) Grist collected the emissions information from permit files the company had submitted to the state.

The results indicated that ethylene oxide concentrations on Dominguez’s block amounted to an estimated cancer risk of 2 in 10,000; that is, if 10,000 people are exposed to that concentration of ethylene oxide over the course of their lives, you could expect 2 to develop cancer from the exposure.

The EPA has never been perfectly clear about what cancer risk level it deems acceptable for the public to shoulder. Instead, it has used risk “benchmarks” to guide decisions around the permitting of new pollution sources near communities. The lower bound in this spectrum of risks is 1 in 1 million, a level above which the agency has said it strives to protect the greatest number of people possible. On the higher end of the spectrum is 1 in 10,000—a level that public health experts have long argued is far too lax, since a person’s cancer risk from pollution exposure accumulates on top of the cancer risk they already have from genetics and other environmental factors. The risk for Dominguez and her family is beyond even that.

According to the air modeler’s results, 603,000 El Paso residents, about 90% of the city’s population, are exposed to a cancer risk above 1 in 1 million just from Cardinal Health’s two warehouses. More than 1,600 people—including many of Dominguez’s neighbors—are exposed to levels above EPA’s acceptability threshold of 1 in 10,000. The analysis also estimated that the risk from Cardinal Health’s warehouse is higher than that of a Sterigenics medical sterilization facility, located just 35 miles away in Santa Teresa, New Mexico. These findings underscore how much ethylene oxide can accumulate in the air simply from off-gassing. To be clear, these figures are based on Cardinal’s own data. Given the questions surrounding the company’s estimates, the risk to Dominguez, her neighbors, and the facility’s workers could be higher.

In 2021, Dominguez gave birth to her second child, and over the next few years, both she and her children began suffering from respiratory issues. Her young son, in particular, developed severe breathing problems, and a respiratory specialist prescribed an inhaler and allergy medication to help him breathe better. Her daughter, now a teenager, complained of persistent headaches. And she, too, began developing sinus headaches.

Meanwhile, Cardinal Health was expanding its operations. In 2023, the company applied to the TCEQ for an updated permit “as quickly as possible.” At the warehouse across town from Dominguez, the company soon expected to receive nearly four times as many trucks carrying sterilized products—potentially up to 10,000 trucks a year—and the increased truck traffic “may increase potential emissions” of ethylene oxide.

Cardinal relied on the 2013 experiment to estimate the facility’s emissions, simply multiplying that concentration by the new maximum number of trucks the facility would be permitted to receive. The back-of-the-envelope calculation led the company to estimate that the warehouse across town from Dominguez would increase its emissions to 1,000 pounds of the chemical per year.

Cardinal also estimated that the medical equipment would off-gas 637 pounds of ethylene oxide inside the warehouse every year. However, it claimed that those emissions are “de minimus,” or insignificant sources of pollution. Under Texas state law, minimal emissions, such as the vapors that might form in a janitorial closet storing solvents or gas produced by running air conditioners or space heaters, may be excluded from permitting requirements.

“Like, if I’m a college professor in school, I don’t want to consider the volatile organic compounds coming out of the marker pens that I’m writing with on the board,” said Ron Sahu, a mechanical engineer and consultant with decades of experience working with state and federal environmental regulators and industrial operators. The exceptions, he said, “were not based on highly toxic compounds like ethylene oxide.”

As required under Texas rules, Cardinal surveyed facilities around the country that emit comparable amounts of ethylene oxide and summarized the technology they use to reduce emissions. Given the volume of the emissions from the warehouse, the most analogous facilities were the sterilizers themselves. The company found two sterilizers in Texas that utilize equipment to reduce their emissions by 99%.

But these options, Cardinal determined, were “cost excessive” and emissions from the warehouse were “very low.” Instead, the company said it would simply “restrict” the number of trucks unloading sterilized products—only three per hour and 10,000 per year. In other words, it would expand its operations, but in a controlled way, in order to forego proven methods of reducing ethylene oxide emissions.

Grist sent TCEQ detailed written questions about the permits it issued to Cardinal. Even though the questions were based on documents the agency has already made publicly available, a spokesperson requested that Grist send a formal records request “due to the level of involvement and the amount of technical information you are requesting.”

Ultimately, in 2023, TCEQ granted Cardinal’s new permit.

At the same time that Cardinal Health was expanding its operations in Texas, the fight to have stricter oversight of ethylene oxide was spreading across the country. Individuals in Lakewood, Colorado, filed private lawsuits for health care damages related to ethylene oxide exposure; others joined class action lawsuits against sterilization companies and the EPA.

Finally, in April 2023, the EPA proposed long-overdue regulations to reduce ethylene oxide emissions from sterilizers. While the draft rule covered emissions from storage centers located on-site, it neglected to include off-site warehouses. Other provisions advocates had hoped for, like mandatory fence-line air monitoring near facilities, were also missing from the draft rule.

Following standard procedure, the EPA then opened a 75-day period for public comment and potential revision to the draft rule. Earthjustice organized a convening of community advocates from across the country to increase pressure on the agency to strengthen its draft. Residents from California, Texas, Puerto Rico, and other places with sterilizers spent two days in Washington, D.C., petitioning members of Congress, meeting with the EPA, and sharing their stories of exposure.

Daniel Savery, a legislative representative at Earthjustice who helped organize the event, told Grist that the meeting with the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation was well attended and that leadership expressed empathy for the stories they heard. But when the agency released the final rule in March 2024, neither off-site warehouses nor mandatory air monitoring was included. The regulations do reference the problem of off-site warehouses and indicate the agency’s intention to collect information about them—a first step that Savery believes wouldn’t have made it into the rule were it not for pressure from the Washington meetings. However, he added, the EPA should have collected information about medical supply warehouses a long time ago.

“This is the EPA’s eighth rodeo on this issue,” Savery said, alluding to the many years advocates have pressed the agency to address ethylene oxide exposure since the chemical was found to be highly toxic in 2016. The EPA’s Office of Inspector General, an independent agency watchdog, had asked the federal regulators as early as 2020 to do a better job informing the public about their exposure to ethylene oxide from the sterilization industry. “The wool is sort of over the country’s eyes for the most part about these emissions sources,” Savery said.

Efforts to rein in ethylene oxide emissions seem unlikely during President Donald Trump’s second term. Trump’s nominee to lead the EPA’s air quality office, Aaron Szabo, was a lobbyist for the sterilization industry, and the agency recently asked sterilizers seeking an exemption from ethylene oxide rules to send their petitions to a dedicated government email address. The Trump administration has since also said in court filings that it plans to “revisit and reconsider” the rule for sterilizers.

A spokesperson for the EPA said they cannot “speak to the decisions of the Biden-Harris administration” and cited the agency’s recent decision to offer exemptions to sterilizers. The spokesperson also referenced a separate EPA decision to regulate ethylene oxide as a pesticide. That decision “could require a specific study for monitoring data on fumigated medical devices to better understand worker exposure to EtO from fumigated medical devices,” the spokesperson said. However, much like the sterilizer rule, the Trump administration could also decide to rescind the pesticide determination.

“Ethylene oxide from these warehouses is just unregulated,” said Sahu, the mechanical engineer. “There’s no control, so everything will eventually find its way to the ambient air.”

Last August, on a cloudy morning in east El Paso, Texas, when most people’s days were just getting started, workers at the Cardinal Health warehouse were sitting in their cars, a stone’s throw from the Dominguez backyard. Having started their shifts at 5 a.m., they were all on break. One young worker was talking to his girlfriend. Another was scrolling on Facebook. And another snacked on Takis, staining her fingers bright red.

Some of their jobs require moving refrigerator-size pallets filled with sterilized medical devices. Others carefully cut open the pallets wrapped in plastic, moving the cardboard boxes containing the medical kits into the warehouse and repackaging them to be trucked to hospitals across the country. They do this with protective gloves, basic face masks, and hairnets—precautions the company urges to ensure the sterility of the medical equipment, not the protection of the workers.

Grist spoke to several of them while they were on break or leaving their shifts. Although none of the workers agreed to speak with Grist reporters on the record, due to a fear of retaliation by their employer, they shared their experiences about working at the warehouse. Most were unaware they were being exposed to ethylene oxide. Some had heard of the chemical but didn’t know the extent of their exposure and its risks.

Grist also distributed flyers to workers and nearby residents explaining the risks of ethylene oxide exposure. Two workers called Grist using the contact number on the flyer and said they had developed cancers that research links to ethylene oxide exposure after they started the job.

Since learning about the warehouse’s emissions, Dominguez said she now thinks twice before letting her young son play in the backyard. “We’re indoors most of the time for that reason,” she said.

Dominguez had been considering buying the property from her boss, but her family’s future in their home is now uncertain.

“I really changed my mind about that,” she said.

This article was originally published by Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Sign up for its newsletter here.

Grist created an informational guide—available in English and Spanish—in collaboration with community organizations, nonprofits, and residents who have pushed for more EtO regulation for years. This booklet contains facts about EtO, as well as ways to get local officials to address emissions, legal resources, and more. You can view, download, print, and share it here.

If you’re a local journalist or a community member who wants to learn more about how Grist investigated this issue and steps you can take to find out more about warehouses in your area, read this.

![[Webinar] AI Is Already Inside Your SaaS Stack — Learn How to Prevent the Next Silent Breach](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiOWn65wd33dg2uO99NrtKbpYLfcepwOLidQDMls0HXKlA91k6HURluRA4WXgJRAZldEe1VReMQZyyYt1PgnoAn5JPpILsWlXIzmrBSs_TBoyPwO7hZrWouBg2-O3mdeoeSGY-l9_bsZB7vbpKjTSvG93zNytjxgTaMPqo9iq9Z5pGa05CJOs9uXpwHFT4/s1600/ai-cyber.jpg?#)

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![Rogue Company Elite tier list of best characters [April 2025]](https://media.pocketgamer.com/artwork/na-33136-1657102075/rogue-company-ios-android-tier-cover.jpg?#)

_Andreas_Prott_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![What’s new in Android’s April 2025 Google System Updates [U: 4/18]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/01/google-play-services-3.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Watch Series 10 Back On Sale for $299! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96657/96657/96657-640.jpg)

![EU Postpones Apple App Store Fines Amid Tariff Negotiations [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97068/97068/97068-640.jpg)

![Apple Slips to Fifth in China's Smartphone Market with 9% Decline [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97065/97065/97065-640.jpg)