This federal program helps families pay utility bills—but Trump just fired the entire staff

As a particularly cold winter sputters to an end, Pennsylvania’s Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which helps residents pay their heating bills, closed on Friday—several weeks earlier than expected. Funding for LIHEAP has dried up because federal workers who administer the program were recently laid off by the Trump administration, said Elizabeth Marx, the executive director at the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project, a legal advocacy group that assists people struggling to pay their utility costs. About $19 million has yet to be sent to the state. The state Public Utility Commission sent a letter to Congess this week about the shortfall and called the fund a “lifeline for Pennsylvania’s most vulnerable households.” Marx said the delay in federal funds couldn’t happen at a worse time. April is known as the start of “termination season,” she said, when her organization sees an uptick in the number of households whose electricity or gas is turned off. State regulations prohibit winter disconnections before April 1. “Every year we have a spike in calls to our emergency hotline because, all at the same time, people are receiving termination notices,” Marx said. “This is a time when the demand for LIHEAP increases dramatically.” LIHEAP is among dozens of aid programs caught short by mass firings in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Part of broad budget cuts by the Trump administration, the entire staff that allocates funds for LIHEAP was eliminated two weeks ago. HHS did not respond to a request for comment. Administered largely by states, LIHEAP distributes more than $4 billion a year to 6.2 million low-income households nationwide to help with heating and cooling costs. Last year, LIHEAP provided assistance to 346,000 Pennsylvanians, including 55,000 people who were in danger of having their heating cut. About $400 million in LIHEAP funding has yet to be sent to the states. In 2025, Pennsylvania had so far received $71 million by early April. Marx said that no one has explained the delay. “The funding hasn’t yet been cut. We just haven’t gotten it,” Marx said. “We have no idea when the remaining amount of funds are going to come to Pennsylvania.” Sanya Carley, the faculty director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, said the gutting of the staff is behind the funding interruption. “With the layoffs at HHS, that means that nobody is there to allocate the remainder during the more extreme, excessive heat months,” she said. LIHEAP is “one of our cornerstone social assistance programs,” said Juanita Constible, a senior advocate for environmental health at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). It can mean the difference between a family being able to afford to stay in their home or not, or to feed themselves or not, she said. Even if funds were sent this week, the program wouldn’t be able to reopen immediately. “You can’t just turn a program like that on a dime,” Marx said. The delay could also mean bad news this summer and beyond. Without help from LIHEAP to pay debts to utility companies that accumulated over the winter, thousands of households could lose power, leaving them with limited access to electricity this summer. The pause in payments will likely drive up demand for aid in the fall, advocates said. LIHEAP also covers maintenance and repair to home furnaces. Utility disconnections can lead to other losses for families scrambling to make ends meet. (Think of a refrigerator full of spoiled groceries.) They can spur evictions and, in some cases, cause children to be removed from homes deemed unsafe. And as Pennsylvania and the rest of the country face increasingly hot summers because of climate change, air-conditioning is no longer a convenience but a life-saving necessity. Prolonged heat exposure exacerbates chronic conditions including asthma, diabetes, and hypertension and can endanger pregnant women, children, and the elderly. LIHEAP was among the programs seen as most critical for helping families in Philadelphia at a climate justice event hosted by Drexel University last week. “The federal government is disinvesting in data to understand health disparities, data to understand climate risk, funding for energy solutions. The LIHEAP program is now at risk,” said Mathy Stanislaus, the executive director of Drexel’s Environmental Collaboratory. “Now more than ever, we really need to figure out how we can link up community-based leadership and priorities for state and local solutions,” Stanislaus said. The event brought together four community groups, called the Philadelphia Climate Justice Collective, to present recommendations for a “just climate transition plan” for the city. Finding solutions for neighborhoods with an atypically high heat index were part of the collective’s report. “The government’s disinvestment and dismantling casts a long shadow,” Stani

As a particularly cold winter sputters to an end, Pennsylvania’s Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which helps residents pay their heating bills, closed on Friday—several weeks earlier than expected.

Funding for LIHEAP has dried up because federal workers who administer the program were recently laid off by the Trump administration, said Elizabeth Marx, the executive director at the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project, a legal advocacy group that assists people struggling to pay their utility costs. About $19 million has yet to be sent to the state.

The state Public Utility Commission sent a letter to Congess this week about the shortfall and called the fund a “lifeline for Pennsylvania’s most vulnerable households.”

Marx said the delay in federal funds couldn’t happen at a worse time.

April is known as the start of “termination season,” she said, when her organization sees an uptick in the number of households whose electricity or gas is turned off. State regulations prohibit winter disconnections before April 1.

“Every year we have a spike in calls to our emergency hotline because, all at the same time, people are receiving termination notices,” Marx said. “This is a time when the demand for LIHEAP increases dramatically.”

LIHEAP is among dozens of aid programs caught short by mass firings in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Part of broad budget cuts by the Trump administration, the entire staff that allocates funds for LIHEAP was eliminated two weeks ago. HHS did not respond to a request for comment.

Administered largely by states, LIHEAP distributes more than $4 billion a year to 6.2 million low-income households nationwide to help with heating and cooling costs. Last year, LIHEAP provided assistance to 346,000 Pennsylvanians, including 55,000 people who were in danger of having their heating cut.

About $400 million in LIHEAP funding has yet to be sent to the states. In 2025, Pennsylvania had so far received $71 million by early April.

Marx said that no one has explained the delay. “The funding hasn’t yet been cut. We just haven’t gotten it,” Marx said. “We have no idea when the remaining amount of funds are going to come to Pennsylvania.”

Sanya Carley, the faculty director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, said the gutting of the staff is behind the funding interruption. “With the layoffs at HHS, that means that nobody is there to allocate the remainder during the more extreme, excessive heat months,” she said.

LIHEAP is “one of our cornerstone social assistance programs,” said Juanita Constible, a senior advocate for environmental health at the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). It can mean the difference between a family being able to afford to stay in their home or not, or to feed themselves or not, she said.

Even if funds were sent this week, the program wouldn’t be able to reopen immediately. “You can’t just turn a program like that on a dime,” Marx said. The delay could also mean bad news this summer and beyond.

Without help from LIHEAP to pay debts to utility companies that accumulated over the winter, thousands of households could lose power, leaving them with limited access to electricity this summer. The pause in payments will likely drive up demand for aid in the fall, advocates said. LIHEAP also covers maintenance and repair to home furnaces.

Utility disconnections can lead to other losses for families scrambling to make ends meet. (Think of a refrigerator full of spoiled groceries.) They can spur evictions and, in some cases, cause children to be removed from homes deemed unsafe. And as Pennsylvania and the rest of the country face increasingly hot summers because of climate change, air-conditioning is no longer a convenience but a life-saving necessity. Prolonged heat exposure exacerbates chronic conditions including asthma, diabetes, and hypertension and can endanger pregnant women, children, and the elderly.

LIHEAP was among the programs seen as most critical for helping families in Philadelphia at a climate justice event hosted by Drexel University last week.

“The federal government is disinvesting in data to understand health disparities, data to understand climate risk, funding for energy solutions. The LIHEAP program is now at risk,” said Mathy Stanislaus, the executive director of Drexel’s Environmental Collaboratory.

“Now more than ever, we really need to figure out how we can link up community-based leadership and priorities for state and local solutions,” Stanislaus said.

The event brought together four community groups, called the Philadelphia Climate Justice Collective, to present recommendations for a “just climate transition plan” for the city. Finding solutions for neighborhoods with an atypically high heat index were part of the collective’s report.

“The government’s disinvestment and dismantling casts a long shadow,” Stanislaus said in an interview, referring to the fallout from federal cuts led by DOGE, Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency.

For example, the North Philadelphia-based nonprofit Esperanza lost a $500,000 grant for Hunting Park that would have covered the cost of weatherizing homes and planting trees. Hunting Park is a neighborhood where summer temperatures routinely register 10 to 15 degrees higher than wealthier and greener areas of the city.

Despite the funding cuts, the collective’s leadership said they will continue working to help Philadelphia’s most underserved residents.

“The federal government is completely erasing the history of environmental justice. The EPA administrator issued a memo two weeks ago that says we’re not going to consider the burdens of communities of color and low-income neighborhoods,” Stanislaus said. “We need to push back.”

One of the participating organizations, the Overbrook Environmental Education Center, lost a promised $700,000 federal grant. “We’re disappointed, but we’re not devastated,” said Jerome Shabazz, its executive director.

“Are we going to rely on these folks to define for us what our dignity should look like, who we should protect and who we should love and who we should give consideration to? How are we going to have an attitude where the most vulnerable amongst us are not the people we want to serve?” he asked. “That’s not acceptable. If we’re talking about climate and environmental justice, then we must be just.”

More than 70% of LIHEAP recipients come from households with at least one senior citizen, person with disabilities, or child under the age of 6.

Constible, of the NRDC, said if LIHEAP disappeared there would be “a lot more evictions.”

“We’d see a lot more potential deaths or serious physical harm. I think we’d see a lot more families trying to make a decision between heating and eating, or stalling medical care that they need,” she said.

Marx said the disruption to LIHEAP funding is occurring as more people are losing access to consistent electricity, water, and gas service. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, last year one in four Pennsylvania households said they had trouble paying their energy bills. Even before this winter, LIHEAP funding had fallen since the 2021-2022 fiscal year, when Pennsylvania received more than $480 million. This year, the state was allocated around $200 million.

Now, experts say the situation is dire. “People will die,” Carley said. “People will die this summer if they cannot cool their homes and they cannot pay their bills.”

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![BPMN-procesmodellering [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/l7l8q49F.png)

-All-will-be-revealed-00-35-05.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-All-will-be-revealed-00-17-36.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-Jack-Black---Steve's-Lava-Chicken-(Official-Music-Video)-A-Minecraft-Movie-Soundtrack-WaterTower-00-00-32_lMoQ1fI.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![What iPhone 17 model are you most excited to see? [Poll]](https://9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/04/iphone-17-pro-sky-blue.jpg?quality=82&strip=all&w=290&h=145&crop=1)

![Hands-On With 'iPhone 17 Air' Dummy Reveals 'Scary Thin' Design [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97100/97100/97100-640.jpg)

![Mike Rockwell is Overhauling Siri's Leadership Team [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97096/97096/97096-640.jpg)

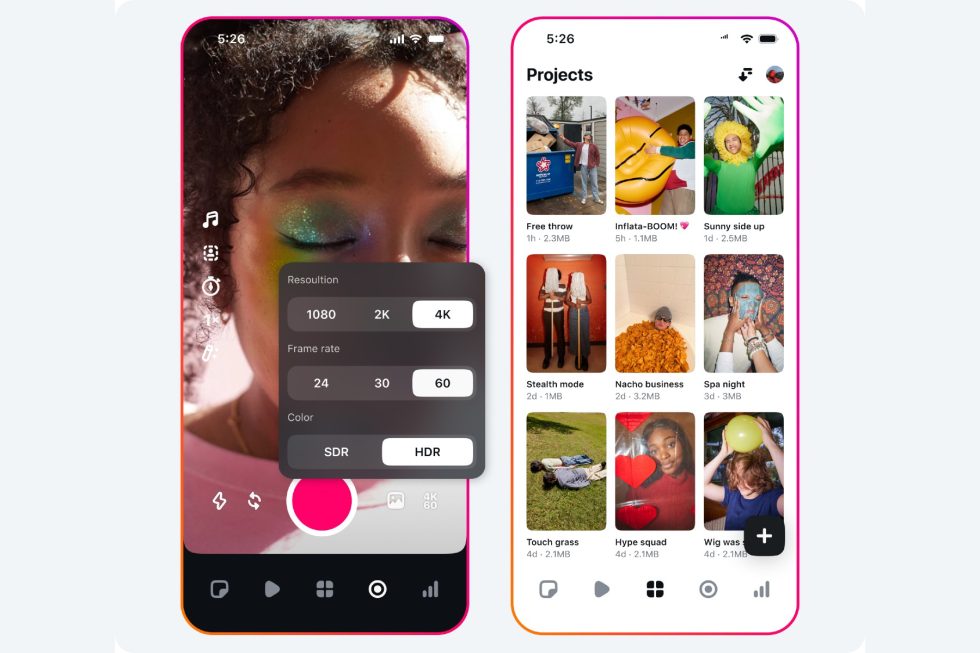

![Instagram Releases 'Edits' Video Creation App [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97097/97097/97097-640.jpg)

![Inside Netflix's Rebuild of the Amsterdam Apple Store for 'iHostage' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97095/97095/97095-640.jpg)