The Thin Line Between Psychological Safety and Underperformance

When I began my professional life a long time ago (on the business side, not in software engineering), feedback used to be direct. If you made a mistake, you'd hear about it - often bluntly - and were expected to improve. There was no buffer between performance and critique. Fast forward to today, and it feels like the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Now, criticism is often seen as a threat to psychological safety, and even well-meant feedback can be interpreted as damaging or watered down to such extent it does not generate any improvement. This shift has raised a difficult but necessary question: have we gone too far in protecting psychological safety at the expense of performance or is it something else we're doing wrong? TL;DR: This isn't a critique of psychological safety - it's a call to reclaim its actual meaning. Where did psychological safety come from? The concept of psychological safety was introduced by Harvard professor Amy Edmondson in 1999. Her research on hospital teams revealed that those who reported more mistakes weren't underperforming - they were simply more transparent. They felt safe enough to speak up, admit failure, and collaborate without fear. The idea gained widespread traction in 2015 through Google's Project Aristotle, which found that psychological safety was the top trait of high-performing teams. This kicked off a wave of company culture initiatives focused on creating safer, more inclusive environments. Since then, psychological safety has become a buzzword in every modern workplace. From HR workshops to engineering offsites, we've been taught that creating a "safe space" is the path to innovation, collaboration, and long-term performance. And to a degree, this is absolutely true. But there's a catch - psychological safety doesn't mean the absence of discomfort. It doesn't mean avoiding criticism. And it certainly doesn't mean lowering the bar. The danger of misinterpretation The problem isn't with psychological safety itself - it's with how it's often misunderstood and misapplied. When teams adopt the language of safety without balancing it with clear standards, accountability, and candid feedback, the result is what Amy Edmondson calls the Comfort Zone. Let's break down her learning zone model, which illustrates this dynamic: Standards.High Standards.Low Safety.High Learning zone (ideal) Comfort zone (complacency) Safety.Low Anxiety zone (fear) Apathy zone (disinterest) In the Learning Zone, people feel safe to speak up and are held to a high bar. Mistakes are seen as opportunities to improve, but not as acceptable outcomes in themselves. It's a productive tension - people are both supported and challenged. But many teams today fall into the Comfort Zone, where psychological safety is mistaken for emotional comfort, and where giving direct feedback is seen as a threat to morale. Here, the language of empathy becomes a shield for mediocrity. Difficult conversations are avoided. Underperformance lingers. High performers get frustrated. What the research actually says Several studies have reinforced the value of psychological safety - but always in the context of clear expectations and performance standards. Amy Edmondson, in her book The Fearless Organization, emphasizes that psychological safety is not about being nice or lowering the bar. It's about creating a space where people can speak up - and then be expected to deliver. Google's Project Aristotle identified psychological safety as critical, but it was only one of several key traits. Others included dependability, structure and clarity, and impact of work. In other words, safety mattered - but so did discipline. A report from McKinsey in 2021 found that teams with both high psychological safety and clear accountability outperformed all others. Teams with only one of the two (e.g., high safety but low standards) showed mixed or even negative results. In Charles Duhigg's book, Smarter Faster Better, high-performing teams are described as having both trust and tension. They allow disagreement, but tie it back to action. They value reflection, but also execution. These studies consistently show that psychological safety is a performance enabler - but only when paired with strong leadership, clarity, and accountability. What it looks like when it goes wrong The consequences of getting this balance wrong are visible in many modern teams. In environments where psychological safety is emphasised without enforcing high standards, teams may appear harmonious on the surface - but underneath they're stalling. The gap between psychological safety and performance isn't just theoretical - it shows up in team dynamics every day. In many modern engineering teams, especially those that prioritise flat hierarchies and consensus-driven cultures, the line between support and accountability can get blurry.

When I began my professional life a long time ago (on the business side, not in software engineering), feedback used to be direct. If you made a mistake, you'd hear about it - often bluntly - and were expected to improve. There was no buffer between performance and critique.

Fast forward to today, and it feels like the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Now, criticism is often seen as a threat to psychological safety, and even well-meant feedback can be interpreted as damaging or watered down to such extent it does not generate any improvement.

This shift has raised a difficult but necessary question: have we gone too far in protecting psychological safety at the expense of performance or is it something else we're doing wrong?

TL;DR: This isn't a critique of psychological safety - it's a call to reclaim its actual meaning.

Where did psychological safety come from?

The concept of psychological safety was introduced by Harvard professor Amy Edmondson in 1999. Her research on hospital teams revealed that those who reported more mistakes weren't underperforming - they were simply more transparent. They felt safe enough to speak up, admit failure, and collaborate without fear.

The idea gained widespread traction in 2015 through Google's Project Aristotle, which found that psychological safety was the top trait of high-performing teams. This kicked off a wave of company culture initiatives focused on creating safer, more inclusive environments.

Since then, psychological safety has become a buzzword in every modern workplace. From HR workshops to engineering offsites, we've been taught that creating a "safe space" is the path to innovation, collaboration, and long-term performance. And to a degree, this is absolutely true.

But there's a catch - psychological safety doesn't mean the absence of discomfort. It doesn't mean avoiding criticism. And it certainly doesn't mean lowering the bar.

The danger of misinterpretation

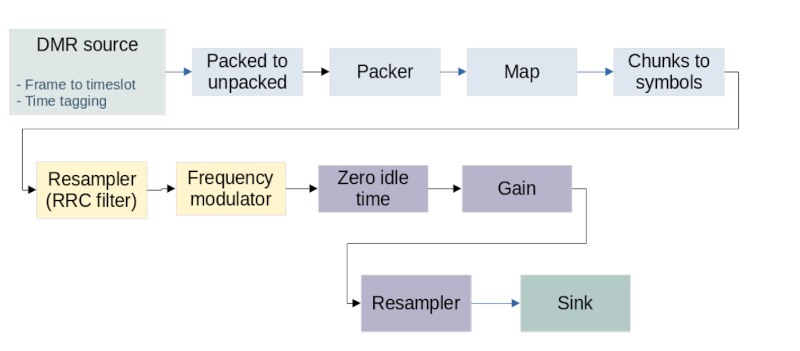

The problem isn't with psychological safety itself - it's with how it's often misunderstood and misapplied. When teams adopt the language of safety without balancing it with clear standards, accountability, and candid feedback, the result is what Amy Edmondson calls the Comfort Zone.

Let's break down her learning zone model, which illustrates this dynamic:

Standards.High Standards.Low

Safety.High Learning zone (ideal) Comfort zone (complacency)

Safety.Low Anxiety zone (fear) Apathy zone (disinterest)

In the Learning Zone, people feel safe to speak up and are held to a high bar. Mistakes are seen as opportunities to improve, but not as acceptable outcomes in themselves. It's a productive tension - people are both supported and challenged.

But many teams today fall into the Comfort Zone, where psychological safety is mistaken for emotional comfort, and where giving direct feedback is seen as a threat to morale. Here, the language of empathy becomes a shield for mediocrity. Difficult conversations are avoided. Underperformance lingers. High performers get frustrated.

What the research actually says

Several studies have reinforced the value of psychological safety - but always in the context of clear expectations and performance standards.

Amy Edmondson, in her book The Fearless Organization, emphasizes that psychological safety is not about being nice or lowering the bar. It's about creating a space where people can speak up - and then be expected to deliver.

Google's Project Aristotle identified psychological safety as critical, but it was only one of several key traits. Others included dependability, structure and clarity, and impact of work. In other words, safety mattered - but so did discipline.

A report from McKinsey in 2021 found that teams with both high psychological safety and clear accountability outperformed all others. Teams with only one of the two (e.g., high safety but low standards) showed mixed or even negative results.

In Charles Duhigg's book, Smarter Faster Better, high-performing teams are described as having both trust and tension. They allow disagreement, but tie it back to action. They value reflection, but also execution.

These studies consistently show that psychological safety is a performance enabler - but only when paired with strong leadership, clarity, and accountability.

What it looks like when it goes wrong

The consequences of getting this balance wrong are visible in many modern teams. In environments where psychological safety is emphasised without enforcing high standards, teams may appear harmonious on the surface - but underneath they're stalling. The gap between psychological safety and performance isn't just theoretical - it shows up in team dynamics every day.

In many modern engineering teams, especially those that prioritise flat hierarchies and consensus-driven cultures, the line between support and accountability can get blurry. Conversations meant to drive clarity are postponed to "protect morale."

Critical feedback is softened or skipped entirely in the name of being "supportive." The intention is good, but the result is often a team that's emotionally safe and operationally stagnant.

In Agile squads, this can show up as endless retrospectives with little follow-through, or sprint planning sessions where no one challenges vague or unrealistic tickets. Code reviews drift into rubber-stamping. Performance issues linger without being addressed directly, and over time, mediocrity becomes normalised.

Meanwhile, high performers begin to disengage. They want feedback, clarity, and challenge - but when those things are missing, motivation fades. Worse, when everyone is treated the same regardless of their output or the quality of their work, it sends a clear message: performance doesn't really matter here.

All of this contributes to a culture where psychological safety turns into emotional insulation. Difficult conversations are seen as threats rather than opportunities. The team may feel cohesive, but not driven. Safe, but not ambitious.

In that comfort zone, teams stop growing.

This isn't psychological safety - it's quiet decline, disguised as empathy.

Reclaiming the balance: Safety + Standards

So how do we walk the tightrope? How can leaders, engineering managers, and ICs foster psychological safety without lowering the bar?

- Redefine Psychological Safety

Remind your team that psychological safety means being safe to speak up, not safe from feedback. You don't build safety by avoiding conflict - you build it by handling conflict well.

- Set Explicit Standards

Be clear about what "good" looks like - code quality, project management, architecture design, delivery timelines, ownership expectations, etc. When standards are vague, people default to their comfort zone, they never seek fixing their skill gaps.

- Make Feedback Normal, Not Exceptional

Create a rhythm for feedback - weekly one-on-ones, retro rituals, code reviews. Feedback shouldn't be an event; it should be a habit.

Coach Through Discomfort

When people struggle, don't rush to protect them from the pain of failure. Instead, walk with them through it. Growth often starts where comfort ends.Hold the Line

Don't let poor performance slide under the guise of empathy. Respect people enough to tell them the truth about how they're doing - and trust them enough to believe they can improve.

A false binary

One of the biggest challenges today is the false binary between kindness and rigour, empathy and accountability. Leaders are often made to feel that they must choose: protect people's emotions or raise the bar.

But great leadership doesn't live at either extreme. It lives in the ability to care deeply and challenge directly.

It's telling someone they missed the mark - and still believing in them. It's holding someone accountable while investing in their growth. That's how trust is built - not through avoidance, but through honesty.

We're living in a workplace culture that values empathy - and that's a good thing. But empathy without standards leads to pity, not progress. And safety without accountability breeds comfort, not competence.

The real goal isn't to avoid discomfort - it's to create an environment where discomfort leads to growth. That's the Learning Zone. That's where high-trust, high-performance teams live.

So let's stop seeing psychological safety as the absence of criticism, and start seeing it as the presence of trust, honesty, and shared ambition. Because the teams that grow the most aren't the ones that feel safe all the time - they're the ones that feel safe enough to be challenged.

That's the thin line, and learning to walk it well certainly is an important leadership skill to be developed.

![[Webinar] AI Is Already Inside Your SaaS Stack — Learn How to Prevent the Next Silent Breach](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiOWn65wd33dg2uO99NrtKbpYLfcepwOLidQDMls0HXKlA91k6HURluRA4WXgJRAZldEe1VReMQZyyYt1PgnoAn5JPpILsWlXIzmrBSs_TBoyPwO7hZrWouBg2-O3mdeoeSGY-l9_bsZB7vbpKjTSvG93zNytjxgTaMPqo9iq9Z5pGa05CJOs9uXpwHFT4/s1600/ai-cyber.jpg?#)

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![[FREE EBOOKS] Machine Learning Hero, AI-Assisted Programming for Web and Machine Learning & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Rogue Company Elite tier list of best characters [April 2025]](https://media.pocketgamer.com/artwork/na-33136-1657102075/rogue-company-ios-android-tier-cover.jpg?#)

_Andreas_Prott_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![What’s new in Android’s April 2025 Google System Updates [U: 4/18]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/01/google-play-services-3.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Watch Series 10 Back On Sale for $299! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96657/96657/96657-640.jpg)

![EU Postpones Apple App Store Fines Amid Tariff Negotiations [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97068/97068/97068-640.jpg)

![Apple Slips to Fifth in China's Smartphone Market with 9% Decline [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97065/97065/97065-640.jpg)