My time on GDX/Undertrail

When I joined the company in September 2015, the cracks were already showing—not in the people, but in the foundation. The software was a tangled mess, barely holding together under the weight of the company’s rapid growth. I was the first in-house developer brought on to fix it, and though leadership at the time was stable—even supportive—the real battle wasn’t with management. It was with the code itself. For months, I fought to untangle what felt like an impossible knot. But some systems aren’t meant to be salvaged. Slowly, almost instinctively, I began redesigning rather than repairing. I didn’t realize it then, but I was stepping into the role of an architect—not by title, but by necessity. And when new developers joined, they followed the structure I laid out, not because I imposed it, but because it made sense. For a while, things worked. The team thrived. The company thrived. We weren’t just fixing problems; we were building something sustainable. Then came the first misstep. The Wrong Tools and the Wrong Decisions Leadership—under pressure to scale—latched onto a competitor’s playbook: No need to reinvent the wheel. They brought in off-the-shelf tools meant to streamline operations. In theory, it was sound. In practice, it was a disaster. These tools weren’t built for us. They warped our processes, forced awkward workarounds, and—worst of all—gave non-technical leaders the illusion of control. The more we relied on them, the more fragile everything became. Predictably, it backfired. A major failure cost the company dearly, and suddenly, everyone was scrambling for solutions. This crisis proved the pattern: when things broke badly enough, my architectural instincts could provide the way forward. The system I proposed wasn't revolutionary, just carefully tailored to our actual needs rather than chasing competitors. And like before, it worked - operations stabilized, and for a brief, golden period, we were untouchable. Then the hierarchy shifted. The Fall of Camilo and the Rise of Silvia Camilo Jiménez, the CTO, had been a steady hand. He wasn’t perfect, but he understood the balance between technical needs and business demands. His relationship with the CEO, however, had been deteriorating for months. When he left, it wasn’t just a leadership gap—it was a power vacuum. Silvia, the PMO, slid into his role. Not because she was the best choice, but because she was there. Her management style was rigid, her technical understanding superficial. She saw deadlines, not systems; authority, not collaboration. Disagreeing with her wasn’t just dissent—it was disrespect. Tasks were assigned without context, decisions made without consultation, and the fragile stability we’d built began to crack under the weight of short-term thinking. I pushed back. Hard. When she overruled technical decisions, I challenged her. When she prioritized speed over sustainability, I refused. It wasn’t rebellion—it was preservation. But to her, it was insubordination. The Breaking Point By July 2017, I’d had enough. I submitted my resignation. Then, a twist: a consultant—el Chino—arrived. He echoed everything we’d been saying, reinforcing what Silvia had dismissed. For a moment, it seemed like sanity would prevail. I considered staying, but only if Silvia’s influence over technical decisions was curbed. She refused. To her, I wasn’t protecting the company—I was undermining her. And because she had the CEO’s ear, my fate was sealed. The Aftermath I wasn’t the first to leave. I wouldn’t be the last. But what stung most wasn’t the exit—it was knowing how easily avoidable it had been. The team fought for me. That mattered. They knew what Silvia didn’t: that good systems aren’t built by authority, but by trust. Less than a year later, Silvia was gone—quietly deemed unfit for the CTO role. Yet on her résumé, she claimed the company’s eventual acquisition was the reason for her departure. Lies. And if there’s a lesson in all of this, it’s that no amount of clever tools or rigid authority can replace the one thing that actually makes a company work—people who care enough to push back when it counts.

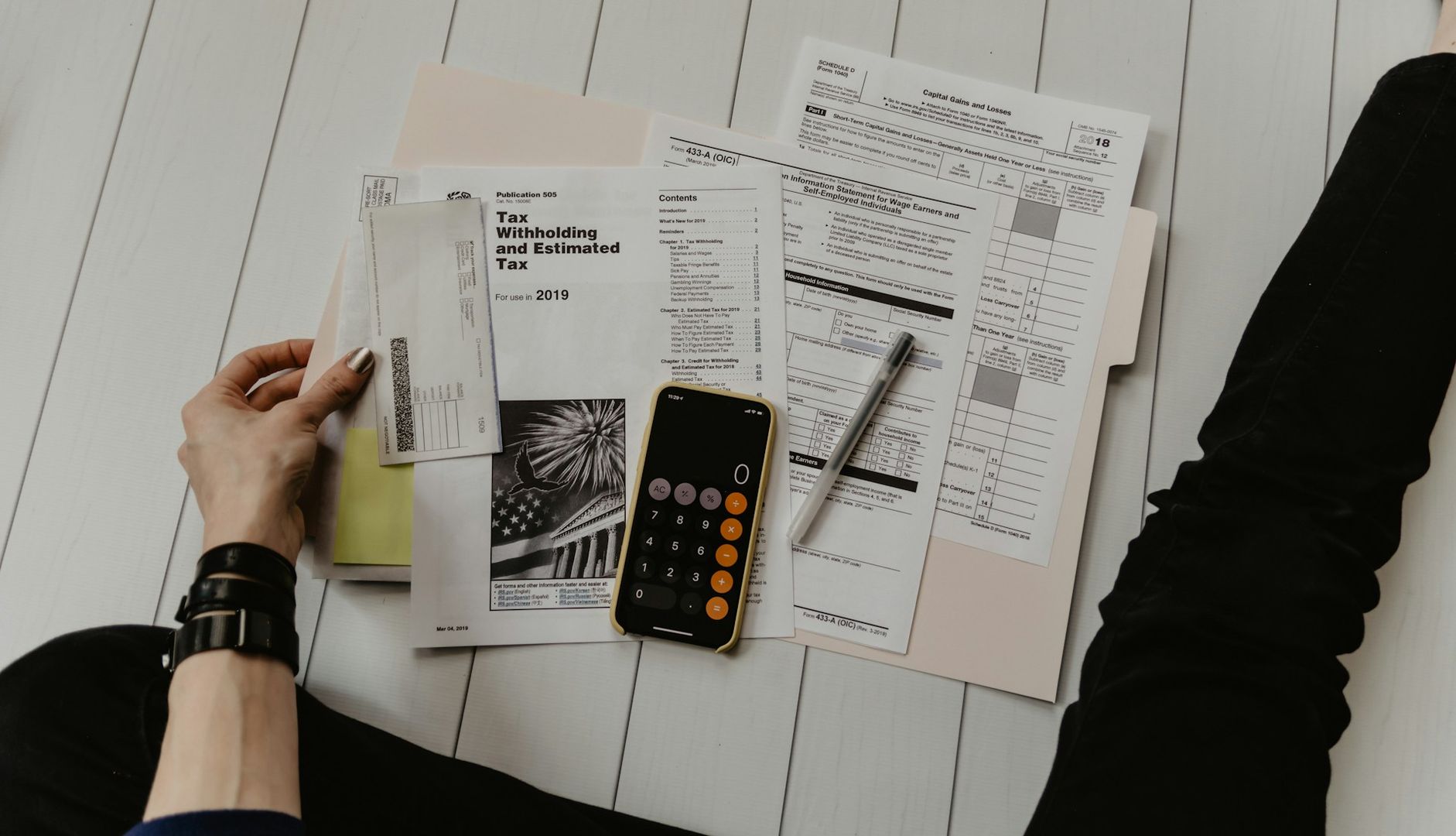

When I joined the company in September 2015, the cracks were already showing—not in the people, but in the foundation. The software was a tangled mess, barely holding together under the weight of the company’s rapid growth. I was the first in-house developer brought on to fix it, and though leadership at the time was stable—even supportive—the real battle wasn’t with management. It was with the code itself.

For months, I fought to untangle what felt like an impossible knot. But some systems aren’t meant to be salvaged. Slowly, almost instinctively, I began redesigning rather than repairing. I didn’t realize it then, but I was stepping into the role of an architect—not by title, but by necessity. And when new developers joined, they followed the structure I laid out, not because I imposed it, but because it made sense.

For a while, things worked. The team thrived. The company thrived. We weren’t just fixing problems; we were building something sustainable.

Then came the first misstep.

The Wrong Tools and the Wrong Decisions

Leadership—under pressure to scale—latched onto a competitor’s playbook: No need to reinvent the wheel. They brought in off-the-shelf tools meant to streamline operations. In theory, it was sound. In practice, it was a disaster.

These tools weren’t built for us. They warped our processes, forced awkward workarounds, and—worst of all—gave non-technical leaders the illusion of control. The more we relied on them, the more fragile everything became. Predictably, it backfired. A major failure cost the company dearly, and suddenly, everyone was scrambling for solutions.

This crisis proved the pattern: when things broke badly enough, my architectural instincts could provide the way forward. The system I proposed wasn't revolutionary, just carefully tailored to our actual needs rather than chasing competitors. And like before, it worked - operations stabilized, and for a brief, golden period, we were untouchable.

Then the hierarchy shifted.

The Fall of Camilo and the Rise of Silvia

Camilo Jiménez, the CTO, had been a steady hand. He wasn’t perfect, but he understood the balance between technical needs and business demands. His relationship with the CEO, however, had been deteriorating for months. When he left, it wasn’t just a leadership gap—it was a power vacuum.

Silvia, the PMO, slid into his role. Not because she was the best choice, but because she was there.

Her management style was rigid, her technical understanding superficial. She saw deadlines, not systems; authority, not collaboration. Disagreeing with her wasn’t just dissent—it was disrespect. Tasks were assigned without context, decisions made without consultation, and the fragile stability we’d built began to crack under the weight of short-term thinking.

I pushed back. Hard.

When she overruled technical decisions, I challenged her. When she prioritized speed over sustainability, I refused. It wasn’t rebellion—it was preservation. But to her, it was insubordination.

The Breaking Point

By July 2017, I’d had enough. I submitted my resignation.

Then, a twist: a consultant—el Chino—arrived. He echoed everything we’d been saying, reinforcing what Silvia had dismissed. For a moment, it seemed like sanity would prevail. I considered staying, but only if Silvia’s influence over technical decisions was curbed.

She refused.

To her, I wasn’t protecting the company—I was undermining her. And because she had the CEO’s ear, my fate was sealed.

The Aftermath

I wasn’t the first to leave. I wouldn’t be the last. But what stung most wasn’t the exit—it was knowing how easily avoidable it had been.

The team fought for me. That mattered. They knew what Silvia didn’t: that good systems aren’t built by authority, but by trust.

Less than a year later, Silvia was gone—quietly deemed unfit for the CTO role. Yet on her résumé, she claimed the company’s eventual acquisition was the reason for her departure. Lies.

And if there’s a lesson in all of this, it’s that no amount of clever tools or rigid authority can replace the one thing that actually makes a company work—people who care enough to push back when it counts.

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The All-in-One Microsoft Office Pro 2019 for Windows: Lifetime License + Windows 11 Pro Bundle (89% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![Is this too much for a modular monolith system? [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/pYL1nsfg.png)

_Andreas_Prott_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![What features do you get with Gemini Advanced? [April 2025]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/02/gemini-advanced-cover.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![Apple Shares Official Trailer for 'Long Way Home' Starring Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97069/97069/97069-640.jpg)

![Apple Watch Series 10 Back On Sale for $299! [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96657/96657/96657-640.jpg)

![EU Postpones Apple App Store Fines Amid Tariff Negotiations [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97068/97068/97068-640.jpg)

![Apple Slips to Fifth in China's Smartphone Market with 9% Decline [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97065/97065/97065-640.jpg)