In Maui, architects are turning surfboard waste into new housing

On Maui’s North Shore, inside an industrial building that was once a pineapple cannery, an architecture office sits across the hall from a surfboard manufacturer. When the architects first moved in, they noticed something: Every few days, the dumpsters in the back would fill up with scraps of foam from making the boards. David Sellers, one of the architects, realized that the foam could be used in a building material—insulated blocks that are typically made from a mix of concrete and new polystyrene foam. “I was just like, ‘We shouldn’t be throwing this away,’” says Sellers, principal architect at the firm, Hawaii Off Grid. “We live on an island, with limited space. So how can we use this to make houses?” [Photo: Hawaii Off Grid] In 2023, the team got a small grant to pursue the idea of recycling the surfboard waste into new blocks. Then came the Lahaina fire, which destroyed more than 2,000 homes and other buildings. The small firm paused the project and focused at first on helping redesign houses. “But we also said, we’re going to need a lot of building materials,” he says. “And we’re going to need building materials that are fire resistant.” The blocks have some advantages. In addition to resisting fire, they’re also four times as strong as a two-by-four framed wall in a hurricane. They’re impervious to mold, mildew, and termites, all issues in Hawaii. The insulation properties are twice what’s required by code. (The fact that it’s energy efficient is especially important for Hawaii Off Grid, which focuses on the carbon footprint of each of its projects; the firm actually requires all of its clients to commit to net zero buildings.) The blocks use only about a third as much cement as is used in cinder blocks. [Photo: Hawaii Off Grid] It’s also an accessible alternative to wood. “Lumber is at an all-time high again, and the availability of building materials is stretched thin,” Sellers says. “This is another option that people can utilize and hopefully help them rebuild faster and not be pinched by the current tariffs that we’re dealing with in the building industry.” To make the blocks, the company uses a large machine to grind up the foam into tiny beads. Then those are mixed with Portland cement, making a consistency that Sellers compares to rice crispy treats, and pressed together in wooden molds. The one-foot-high blocks are five feet long, making them faster to stack together during construction. The design-build firm has just completed its first house using the surfboard-waste-based blocks, on the edge of the burn zone in Lahaina. More are coming. Though the fire happened 20 months ago, the process of rebuilding is just beginning, delayed by the need to decontaminate properties and by red tape. Now, as construction begins to ramp up, materials will be in more demand. [Photo: Hawaii Off Grid] With the volume of foam waste produced by its neighbor alone, the firm has calculated that it would have enough to build 10 to 20 houses a year, much more than it currently needs as a small firm. Sellers has also talked to companies like Lowe’s about recycling foam packaging after appliance deliveries. (In theory, old surfboards could also be recycled, though surfers tend to hang on to old boards and display them rather than throw them away.) The idea could be replicated by other builders, Sellers says. But he’s hoping that polystyrene foam can eventually be phased out—at which point, they’d stop using the blocks as a building material. “I hope we won’t be using petroleum-based solutions, moving forward,” he says. Surfboard companies are already experimenting with alternative materials, and other companies are trying to find foam alternatives for packaging. For now, the architects plan to keep recycling as much foam as possible to keep it out of the dump and out of nature. “We have a stockpile of foam,” Sellers says. “We’re trying to not let any foam go in the landfill.”

On Maui’s North Shore, inside an industrial building that was once a pineapple cannery, an architecture office sits across the hall from a surfboard manufacturer. When the architects first moved in, they noticed something: Every few days, the dumpsters in the back would fill up with scraps of foam from making the boards.

David Sellers, one of the architects, realized that the foam could be used in a building material—insulated blocks that are typically made from a mix of concrete and new polystyrene foam. “I was just like, ‘We shouldn’t be throwing this away,’” says Sellers, principal architect at the firm, Hawaii Off Grid. “We live on an island, with limited space. So how can we use this to make houses?”

In 2023, the team got a small grant to pursue the idea of recycling the surfboard waste into new blocks. Then came the Lahaina fire, which destroyed more than 2,000 homes and other buildings. The small firm paused the project and focused at first on helping redesign houses. “But we also said, we’re going to need a lot of building materials,” he says. “And we’re going to need building materials that are fire resistant.”

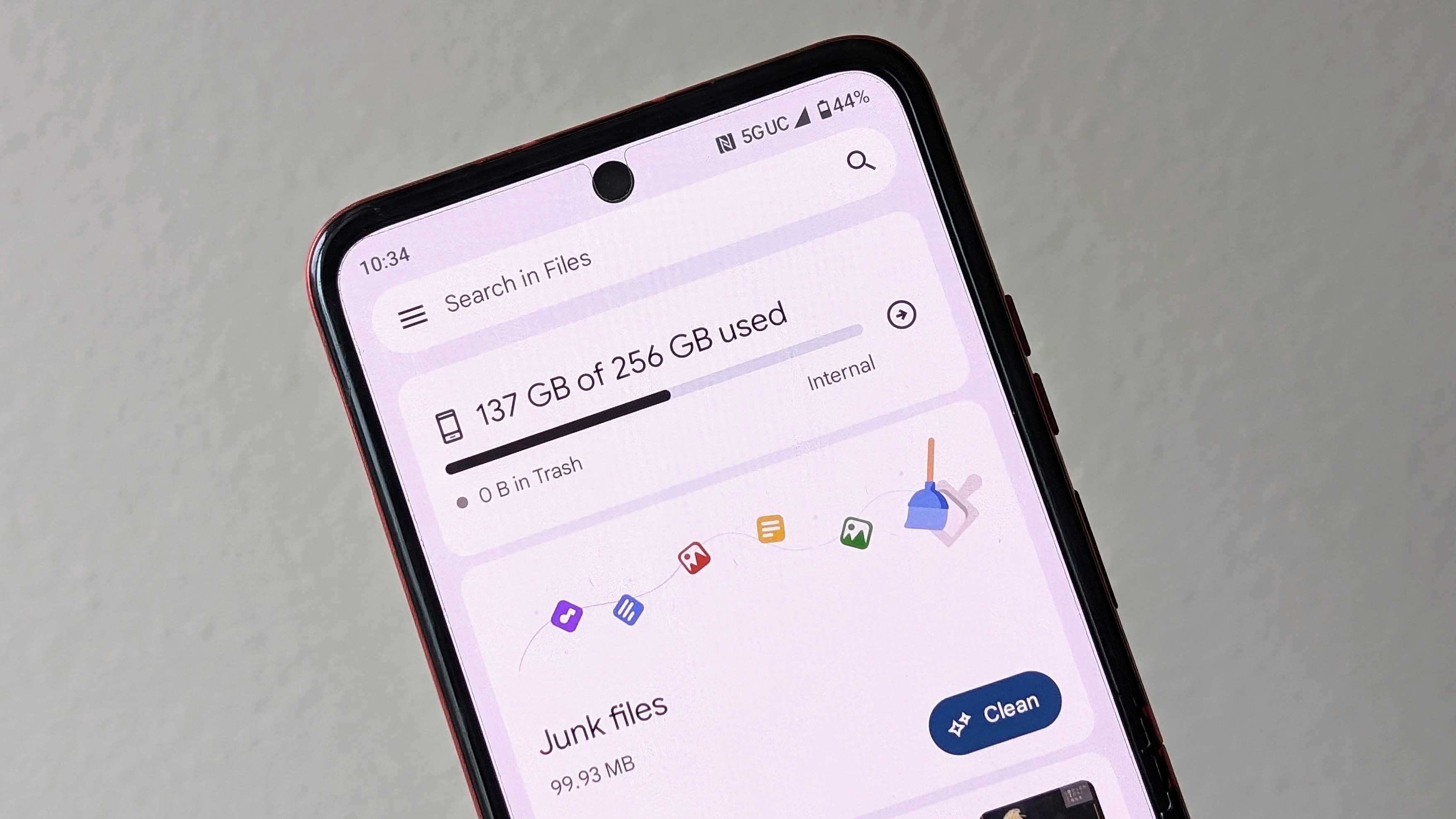

The blocks have some advantages. In addition to resisting fire, they’re also four times as strong as a two-by-four framed wall in a hurricane. They’re impervious to mold, mildew, and termites, all issues in Hawaii. The insulation properties are twice what’s required by code. (The fact that it’s energy efficient is especially important for Hawaii Off Grid, which focuses on the carbon footprint of each of its projects; the firm actually requires all of its clients to commit to net zero buildings.) The blocks use only about a third as much cement as is used in cinder blocks.

It’s also an accessible alternative to wood. “Lumber is at an all-time high again, and the availability of building materials is stretched thin,” Sellers says. “This is another option that people can utilize and hopefully help them rebuild faster and not be pinched by the current tariffs that we’re dealing with in the building industry.”

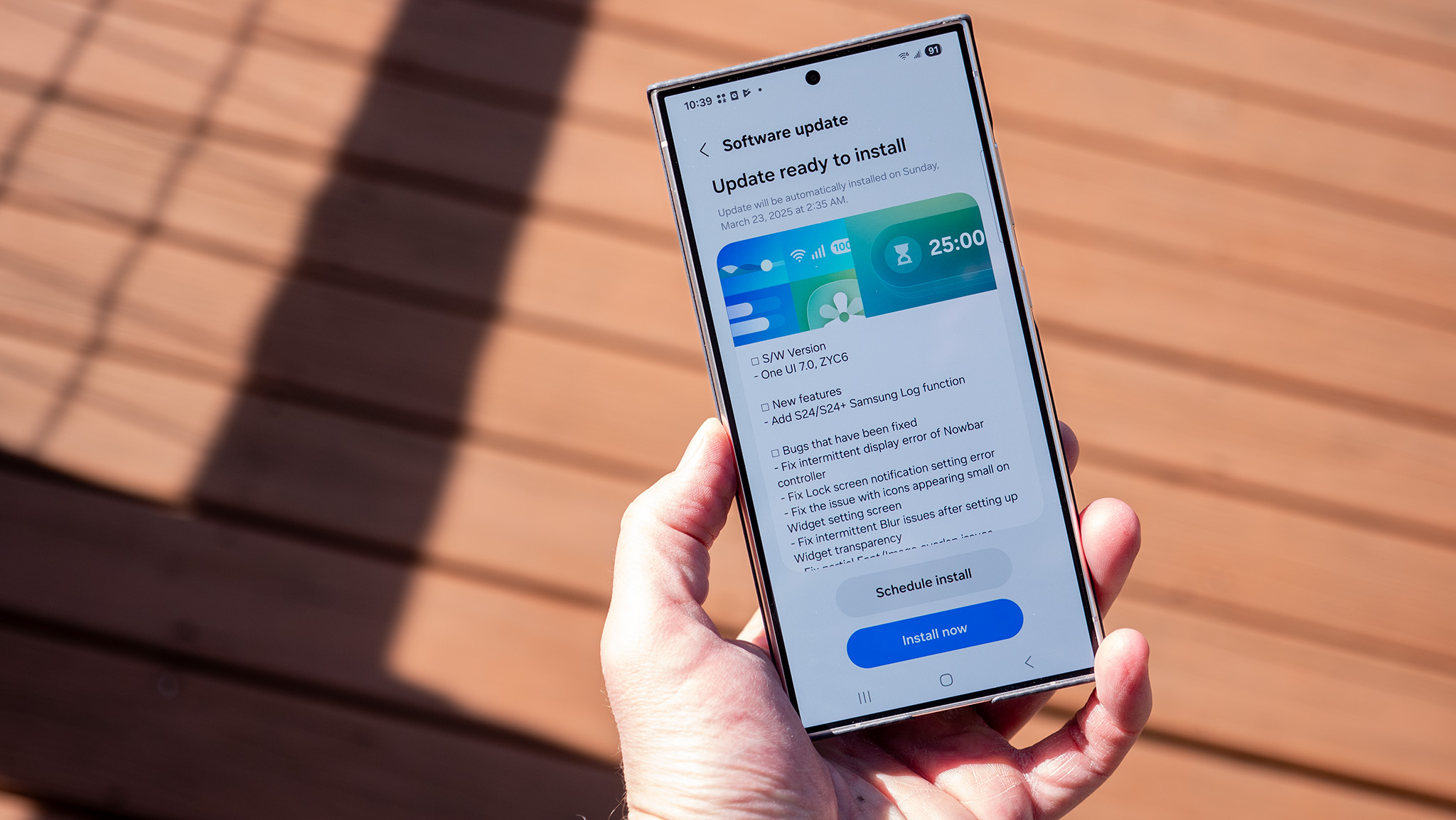

To make the blocks, the company uses a large machine to grind up the foam into tiny beads. Then those are mixed with Portland cement, making a consistency that Sellers compares to rice crispy treats, and pressed together in wooden molds. The one-foot-high blocks are five feet long, making them faster to stack together during construction.

The design-build firm has just completed its first house using the surfboard-waste-based blocks, on the edge of the burn zone in Lahaina. More are coming. Though the fire happened 20 months ago, the process of rebuilding is just beginning, delayed by the need to decontaminate properties and by red tape. Now, as construction begins to ramp up, materials will be in more demand.

With the volume of foam waste produced by its neighbor alone, the firm has calculated that it would have enough to build 10 to 20 houses a year, much more than it currently needs as a small firm. Sellers has also talked to companies like Lowe’s about recycling foam packaging after appliance deliveries. (In theory, old surfboards could also be recycled, though surfers tend to hang on to old boards and display them rather than throw them away.)

The idea could be replicated by other builders, Sellers says. But he’s hoping that polystyrene foam can eventually be phased out—at which point, they’d stop using the blocks as a building material. “I hope we won’t be using petroleum-based solutions, moving forward,” he says. Surfboard companies are already experimenting with alternative materials, and other companies are trying to find foam alternatives for packaging. For now, the architects plan to keep recycling as much foam as possible to keep it out of the dump and out of nature. “We have a stockpile of foam,” Sellers says. “We’re trying to not let any foam go in the landfill.”

![[The AI Show Episode 142]: ChatGPT’s New Image Generator, Studio Ghibli Craze and Backlash, Gemini 2.5, OpenAI Academy, 4o Updates, Vibe Marketing & xAI Acquires X](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20142%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] The Premium Learn to Code Certification Bundle (97% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![From drop-out to software architect with Jason Lengstorf [Podcast #167]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1743796461357/f3d19cd7-e6f5-4d7c-8bfc-eb974bc8da68.png?#)

-Mario-Kart-World-Hands-On-Preview-Is-It-Good-00-08-36.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?#)

(1).jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

_Igor_Mojzes_Alamy.jpg?#)

.webp?#)

.webp?#)

![Apple Considers Delaying Smart Home Hub Until 2026 [Gurman]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96946/96946/96946-640.jpg)

![iPhone 17 Pro Won't Feature Two-Toned Back [Gurman]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96944/96944/96944-640.jpg)

![Tariffs Threaten Apple's $999 iPhone Price Point in the U.S. [Gurman]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96943/96943/96943-640.jpg)